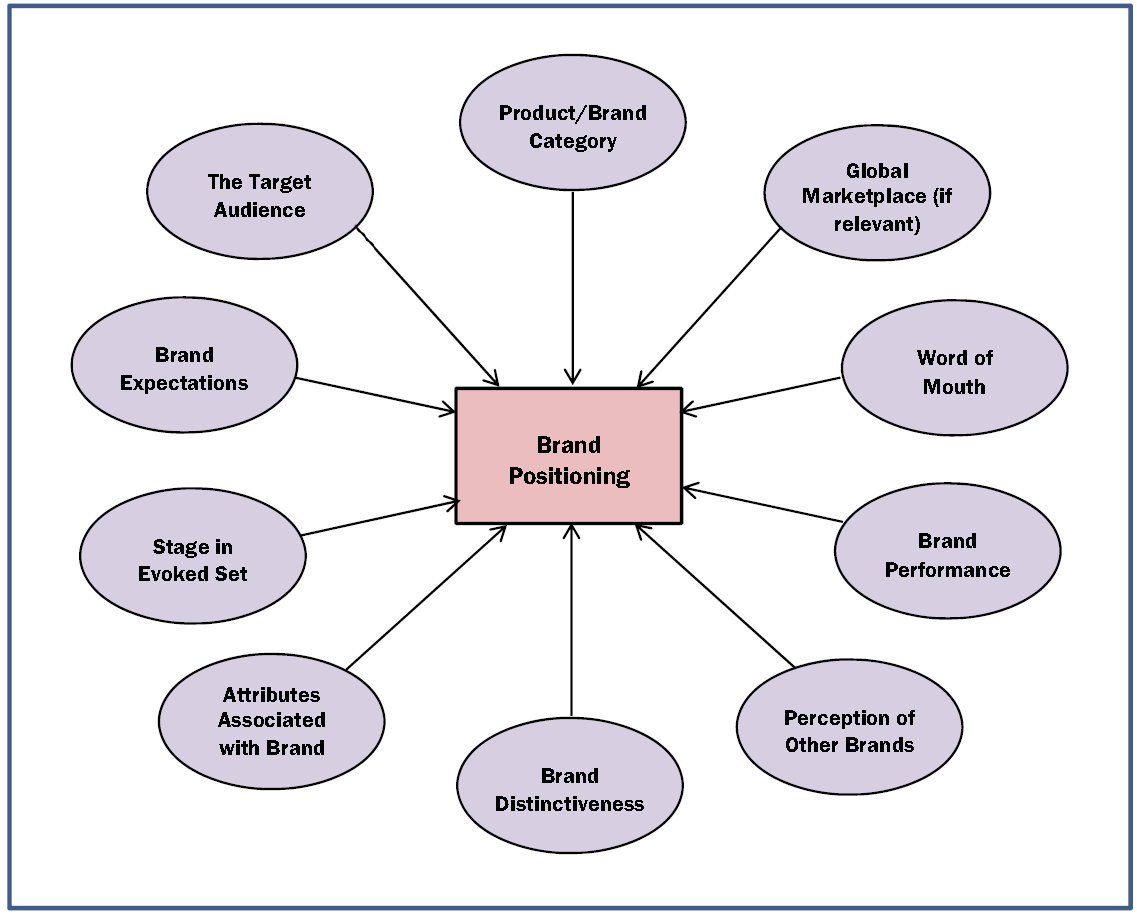

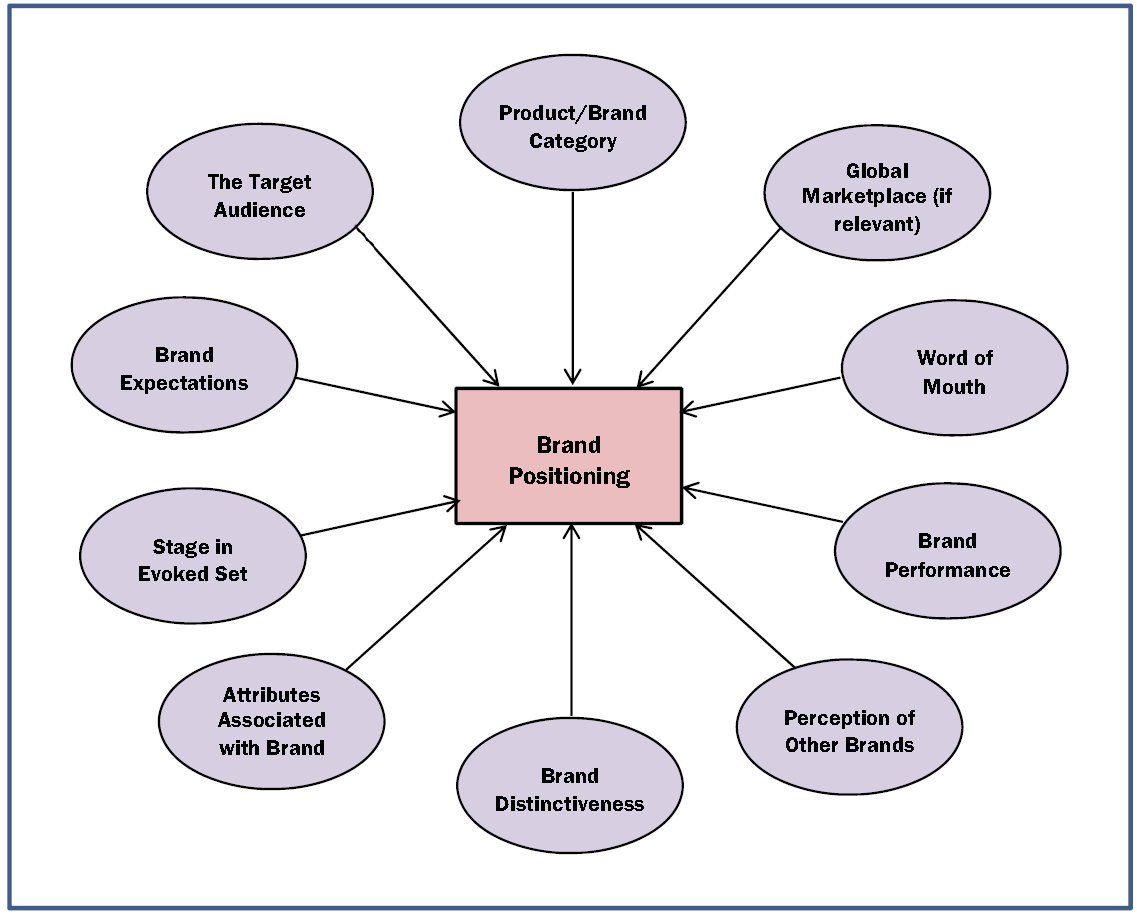

Figure 1: Selected Factors That Affect a Brand’s Positioning

If the information processing of color TVs as a product category is mostly guided by a few distinct brands, then the new brand’s character may be best understood by relating it to an exemplar brand (e.g., a Sony). On the other hand, if information processing is mainly dominated by a mental representation formed from common product category attributes, then describing a new brand’s performance on these attributes may be the best positioning option. In both instances, attributes typical of the category would be used since the positioning emphasis is on association.

The Target Audience–It is necessary to be clear about the target market/s sought for a positioning strategy to be effective. Because the relationship between brand positioning and the consumer’s desired “self” have been widely covered in the literature, it is clear that the brand image projected must match with the desired “self” of the specified target market. For instance, see Dolich (1969); Swaminathan, Page, and Gürhan-Canli (2007); Malär, Krohmer, Hoyer, and Nyffenegger (2011); and Harmon-Kizer, Kumar, Ortinau, and Stock (2013).

Brand Expectations–For each brand category and target market, there is a separate set of expectations about a brand that impact its positioning. Typically, the goal is to attain “brand love” (Batra, Ahuvia, and Bagozzi, 2012) by the target audience. A way plot out brand expectations is to use brand concept (positioning) maps. Consider the work on this by John, et al., for example (2006):

The BCM method involves a consensus brand map, which identifies the core associations that consumers connect to the brand and how these associations are interconnected. Our approach gathers perceptions using structured elicitation, mapping, and aggregation procedures. First, elicitation can use existing consumer research, letting a firm reduce time and expense. Second, because mapping is structured, respondents can complete the task quickly, without extensive interviews. This makes BCM suitable for data collection venues such as mall intercepts and focus groups, and allows for collection of larger and broader samples. Finally, because aggregation involves relatively straightforward use of decision rules, obtaining a consensus brand map is less subjective and does not require specialized training. These advantages allow for construction of consensus brand maps for different market segments, geographic segments, or constituencies.

Stage in Evoked Set–The perception of a brand partially depends on where it falls in a consumer’s evoked set. This concept was first described by Howard (1963) more than 50 years and remains a vital process today. It was expanded by Narayana and Markin (1975, p. 1):

A consumer is either aware or unaware of the existence of any product class. The set of brands in a given product class of which the consumer is aware is denoted by the awareness set. It is from the brands in this set that a consumer makes a purchase choice. But a consumer is apt to reduce the deliberative dilemma by narrowing the category further and selecting from a smaller group of brands, often called an evoked set. Because the consumer appears to make a purchase decision for a product from among the brands in the evoked set, the seller must try to organize its efforts in such a way that its particular brand is positioned with those select few in the buyer’s cognitive field. This task involves more than simply ensuring consumer awareness of the brand’s existence.

Attributes Associated with Brand–Each brand represents several attributes. Some attributes may be unknown, perhaps because of the stage that the brand falls into within a target audience’s evoked set. Attributes that are known by the target audience may be tangible (such as miles per gallon or liter for a particular auto) and/or intangible (such as the feeling a consumer has when driving a given auto brand). All attributes known by the consumer–and perceived by him or her–contribute to a brand’s position. For example, see Aaker (1997), Ivens and Valta (2012), and Loroz and Braig (2015).

Brand Distinctiveness–A major work on brand distinctiveness remains Levitt’s (1980) “Marketing Success Through Differentiation–Of Anything.” Consider the meaning of an augmented product (p. 87):

Differentiation is not limited to giving the customer what he expects. What he expects may be augmented by things he has never thought about. When a computer manufacturer implants a diagnostic module that automatically locates the source of failure or breakdown inside his equipment (as some now do), he has taken the product beyond what was required or expected by the buyer. It has become an augmented product. When a securities brokerage firm includes with its customers’ monthly statements a current balance sheet for each customer and an analysis of sources and disposition of funds, that firm has augmented its product beyond what was required or expected by the buyer. When a manufacturer of health and beauty aids offers warehouse management advice and training programs for the employees of its distributors, that company too has augmented its product beyond what was required or expected by the buyer.

Perception of Other Brands–The positioning of a given brand is impacted by the existence of and perceived positioning of competitive brands, as these illustrations indicate. Manufacturer and private brands have distinct positions in the marketplace, most often driven by price (see Pepe, Abratt, and Dion 2012; and Choi and Fredj, 2013). Brand positioning competition varies by market segment and product sub-category (see Wedel and Zhang, 2004). Niche brands often compete better by not going head-on with large competitors (see Paharia, Avery, and Keinan, 2014). First-mover brands and second-mover brands frequently compete with one another throughout the consumer’s diffusion process (see Kim, 2013). Finally as David A. Aaker (2012, p. 43), puts it:

The most common basis of competition is to win the brand preference battle with a “my brand is better than your brand” strategy in well-established categories and sub-categories. Most marketing budgets are allocated in this way and generate no discernible change in sales or market share. None! There is too much market inertia. The second basis of competition is to win the brand relevance competition by creating new categories or sub-categories for which competitors are irrelevant and by building barriers that make it hard for them to become relevant. Winning this second competitive arena, with rare exceptions, is only way to gain real growth.

Brand Performance–Once a given brand has been bought, its actual performance relative to expectations then come into play. This applies to both goods and services. As Dwivedi (2014) notes:

The roles of performance satisfaction and perceived value cannot be understated, especially for purely intangible services. Without support from physical evidence, consumers are likely to base their brand evaluations heavily on whether their service expectations are being met and whether they feel that they are receiving value from a brand or not. Thus, firms must develop and nurture capabilities that are critical to providing customer satisfaction as well as value. Firms must communicate the service expectations that can be met. The failure to meet these expectations would result in consumer dissatisfaction with potentially serious repercussions.

Word of Mouth–After the target audience sees how well a given brand performs, word of mouth (WOM)–positive and/or negative–affects the brand’s positioning. The word-of-mouth process has greatly proliferated due to social media (eWOM). In a recent study, Lovett, Peres, and Shachar (2013) found that brands and WOM are closely related: “Brand characteristics play an important role in explaining the level of WOM. Furthermore, these results are consistent with the theoretical framework we present, which posits that the brand characteristics affect WOM through three drivers: social , emotional, and functional.” Communications are further discussed later in this paper.

Global View (if relevant)–For brands that are marketed in multiple countries, there are particular challenges in positioning related to language, culture, product uses, and other factors. A global brand may be harder to position consistently than regional or local brands. For good review articles, see Akaka and Alden (2010) and Hassan and Craft (2012).

Generating Brand Equity/Strength

With careful brand positioning, a firm seeks a good return on investment and strong brand equity. What exactly is brand equity? Here is one perspective (“Common Language in Marketing: Dictionary”):

The purpose of brand equity metrics is to measure the value of a brand. A brand encompasses the name, logo, image, and perceptions that identify a product, service, or provider in customers’ minds. It takes shape in advertising, packaging, and other marketing communications, and becomes a focus of the consumer relationship. In time, a brand comes to embody a promise about the goods it identifies–a promise about quality, performance, or other dimensions of value, which can affect consumer choices among competing products. When consumers trust a brand and find it relevant, they may select offerings associated with that brand over those of competitors, even at a higher price. When a brand’s promise extends beyond a particular product, its owner may leverage it to enter new markets. For these reasons, a brand can hold great value, known as brand equity.

There is a rich literature on brand equity. Here is a cross-section: Biel (1992); de Chernatony, Riley, and Harris (1998); Keller (1999b); Broyles, Schumann, and Leingpibul (2009); Das, Stenger, and Ellis (2009); French and Smith (2013); and Ahmad and Thyagaraj (2014).

The Role of Communications, Including New Media

As most firms recognize, the once standard communications model of advertising to consumers in a one-way conversation has been turned on its head by new media whereby consumers can widely discuss their likes, dislikes, and experiences with given brands. When a story about a brand goes “viral,” it can have tremendous positive results, as with the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge which has raised tens of millions of dollars to fight this devastating disease. Or a viral campaign can have a strong negative impact, such as the social media backlash against a Nationwide Insurance TV commercial during the 2015 Super Bowl (O’Reilly, 2015): “The ad, which featured a boy talking about all the life achievements he missed out on because he died in an accident, was an attempt to raise awareness about the fact that preventable childhood accidents are the leading cause of childhood death.”

The multi-faced literature on the evolving role of brand communications includes such topics as: how online ads buils brands (Hollis, 2005); brand positioning by search engine marketing (Dou, et al., 2010); social media and brand equity (Zailskaite-Jakste and Kuvykaite, 2013); branding and digital influencers (Uzunoğlu and Kip, 2014); the damage from negative social media (Corstjens and Umblijs, 2012); brand engagement (Hollebeek, Glynn, and Brodie, 2014); puffery in advertisements (Xu and Wyer Jr., 2010); and social brand planning (Stauffer, 2012).

Corporate Branding

Most companies, including virtually all business-to-business firms, emphasize their corporate names to convey overall brand positioning messages to various stakeholders. When stakeholders–including customers–are aware of the corporate brand and associate it with the individual products offered (and vice versa), the corporate (parent) image can positively or negatively affect these products, and even how firms’ employees are perceived. Weidman, et al. (2013, p. 202) note that:

The heritage aspect of a [corporate] brand adds the association of depth, authenticity, and credibility in the tension between the past, present, and future. A company deeply rooted in tradition can use its long, rich heritage to stress its unambiguous identity, which is strongly connected with reputation and perceived image. The continuity with the past illustrates an effort to achieve trust and recognition as a heritage brand between the organization and its stakeholders. Longstanding corporate roots and values are the basis for creating new ideas.