v

Solution

(1) Insert the value of the latent heat from Table 14.2, L v = 2430 kJ/kg = 2430 J/g . This yields

m

(14.42)

t = 120 J/s

2430 J/g = 0.0494 g/s = 2.96 g/min.

Discussion

Evaporating about 3 g/min seems reasonable. This would be about 180 g (about 7 oz) per hour. If the air is very dry, the sweat may evaporate

without even being noticed. A significant amount of evaporation also takes place in the lungs and breathing passages.

Another important example of the combination of phase change and convection occurs when water evaporates from the oceans. Heat is removed

from the ocean when water evaporates. If the water vapor condenses in liquid droplets as clouds form, heat is released in the atmosphere. Thus,

there is an overall transfer of heat from the ocean to the atmosphere. This process is the driving power behind thunderheads, those great cumulus

clouds that rise as much as 20.0 km into the stratosphere. Water vapor carried in by convection condenses, releasing tremendous amounts of

energy. This energy causes the air to expand and rise, where it is colder. More condensation occurs in these colder regions, which in turn drives the

cloud even higher. Such a mechanism is called positive feedback, since the process reinforces and accelerates itself. These systems sometimes

produce violent storms, with lightning and hail, and constitute the mechanism driving hurricanes.

Figure 14.20 Cumulus clouds are caused by water vapor that rises because of convection. The rise of clouds is driven by a positive feedback mechanism. (credit: Mike Love)

490 CHAPTER 14 | HEAT AND HEAT TRANSFER METHODS

Figure 14.21 Convection accompanied by a phase change releases the energy needed to drive this thunderhead into the stratosphere. (credit: Gerardo García Moretti )

Figure 14.22 The phase change that occurs when this iceberg melts involves tremendous heat transfer. (credit: Dominic Alves)

The movement of icebergs is another example of convection accompanied by a phase change. Suppose an iceberg drifts from Greenland into

warmer Atlantic waters. Heat is removed from the warm ocean water when the ice melts and heat is released to the land mass when the iceberg

forms on Greenland.

Check Your Understanding

Explain why using a fan in the summer feels refreshing!

Solution

Using a fan increases the flow of air: warm air near your body is replaced by cooler air from elsewhere. Convection increases the rate of heat

transfer so that moving air “feels” cooler than still air.

14.7 Radiation

You can feel the heat transfer from a fire and from the Sun. Similarly, you can sometimes tell that the oven is hot without touching its door or looking

inside—it may just warm you as you walk by. The space between the Earth and the Sun is largely empty, without any possibility of heat transfer by

convection or conduction. In these examples, heat is transferred by radiation. That is, the hot body emits electromagnetic waves that are absorbed by

our skin: no medium is required for electromagnetic waves to propagate. Different names are used for electromagnetic waves of different

wavelengths: radio waves, microwaves, infrared radiation, visible light, ultraviolet radiation, X-rays, and gamma rays.

CHAPTER 14 | HEAT AND HEAT TRANSFER METHODS 491

Figure 14.23 Most of the heat transfer from this fire to the observers is through infrared radiation. The visible light, although dramatic, transfers relatively little thermal energy.

Convection transfers energy away from the observers as hot air rises, while conduction is negligibly slow here. Skin is very sensitive to infrared radiation, so that you can

sense the presence of a fire without looking at it directly. (credit: Daniel X. O’Neil)

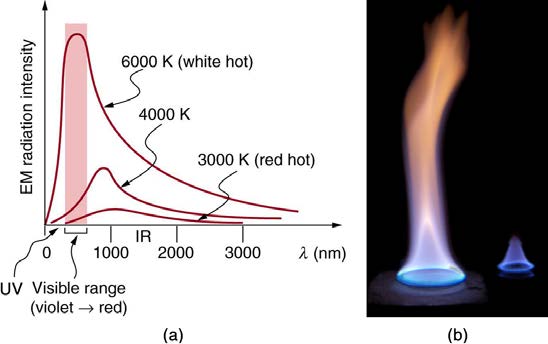

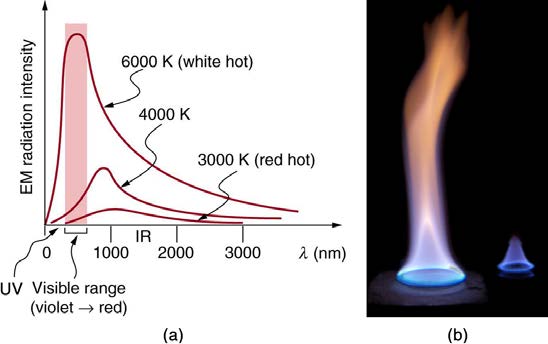

The energy of electromagnetic radiation depends on the wavelength (color) and varies over a wide range: a smaller wavelength (or higher frequency)

corresponds to a higher energy. Because more heat is radiated at higher temperatures, a temperature change is accompanied by a color change.

Take, for example, an electrical element on a stove, which glows from red to orange, while the higher-temperature steel in a blast furnace glows from

yellow to white. The radiation you feel is mostly infrared, which corresponds to a lower temperature than that of the electrical element and the steel.

The radiated energy depends on its intensity, which is represented in the figure below by the height of the distribution.

Electromagnetic Waves explains more about the electromagnetic spectrum and Introduction to Quantum Physics discusses how the decrease in wavelength corresponds to an increase in energy.

Figure 14.24 (a) A graph of the spectra of electromagnetic waves emitted from an ideal radiator at three different temperatures. The intensity or rate of radiation emission

increases dramatically with temperature, and the spectrum shifts toward the visible and ultraviolet parts of the spectrum. The shaded portion denotes the visible part of the

spectrum. It is apparent that the shift toward the ultraviolet with temperature makes the visible appearance shift from red to white to blue as temperature increases. (b) Note the

variations in color corresponding to variations in flame temperature. (credit: Tuohirulla)

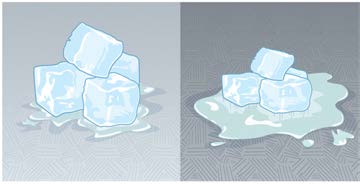

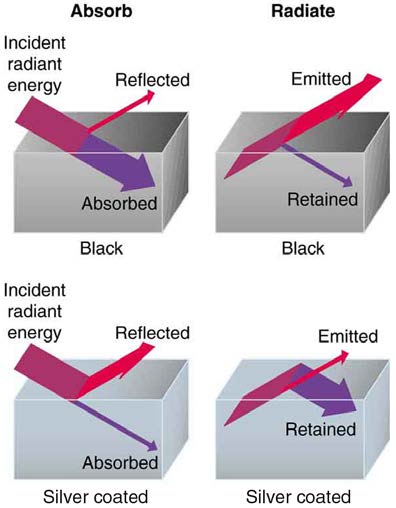

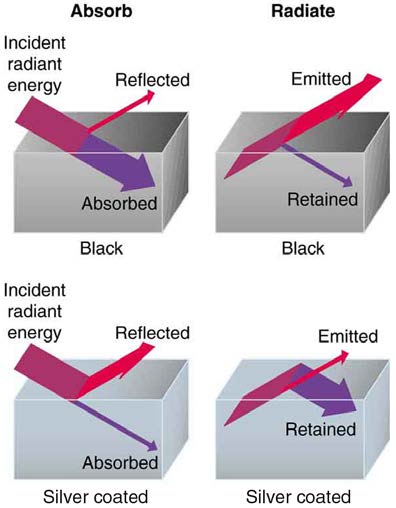

All objects absorb and emit electromagnetic radiation. The rate of heat transfer by radiation is largely determined by the color of the object. Black is

the most effective, and white is the least effective. People living in hot climates generally avoid wearing black clothing, for instance (see Take-Home

Experiment: Temperature in the Sun). Similarly, black asphalt in a parking lot will be hotter than adjacent gray sidewalk on a summer day, because

black absorbs better than gray. The reverse is also true—black radiates better than gray. Thus, on a clear summer night, the asphalt will be colder

than the gray sidewalk, because black radiates the energy more rapidly than gray. An ideal radiator is the same color as an ideal absorber, and

captures all the radiation that falls on it. In contrast, white is a poor absorber and is also a poor radiator. A white object reflects all radiation, like a

mirror. (A perfect, polished white surface is mirror-like in appearance, and a crushed mirror looks white.)

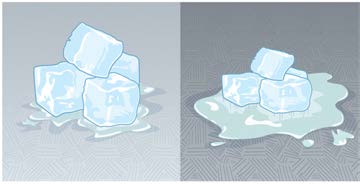

Figure 14.25 This illustration shows that the darker pavement is hotter than the lighter pavement (much more of the ice on the right has melted), although both have been in

the sunlight for the same time. The thermal conductivities of the pavements are the same.

492 CHAPTER 14 | HEAT AND HEAT TRANSFER METHODS

Gray objects have a uniform ability to absorb all parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. Colored objects behave in similar but more complex ways,

which gives them a particular color in the visible range and may make them special in other ranges of the nonvisible spectrum. Take, for example, the

strong absorption of infrared radiation by the skin, which allows us to be very sensitive to it.

Figure 14.26 A black object is a good absorber and a good radiator, while a white (or silver) object is a poor absorber and a poor radiator. It is as if radiation from the inside is reflected back into the silver object, whereas radiation from the inside of the black object is “absorbed” when it hits the surface and finds itself on the outside and is strongly

emitted.

The rate of heat transfer by emitted radiation is determined by the Stefan-Boltzmann law of radiation:

Q

(14.43)

t = σeAT 4,

where σ = 5.67×10−8 J/s ⋅ m2 ⋅ K4 is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, A is the surface area of the object, and T is its absolute temperature in

kelvin. The symbol e stands for the emissivity of the object, which is a measure of how well it radiates. An ideal jet-black (or black body) radiator

has e = 1 , whereas a perfect reflector has e = 0 . Real objects fall between these two values. Take, for example, tungsten light bulb filaments

which have an e of about 0.5 , and carbon black (a material used in printer toner), which has the (greatest known) emissivity of about 0.99 .

The radiation rate is directly proportional to the fourth power of the absolute temperature—a remarkably strong temperature dependence.

Furthermore, the radiated heat is proportional to the surface area of the object. If you knock apart the coals of a fire, there is a noticeable increase in

radiation due to an increase in radiating surface area.

Figure 14.27 A thermograph of part of a building shows temperature variations, indicating where heat transfer to the outside is most severe. Windows are a major region of

heat transfer to the outside of homes. (credit: U.S. Army)

Skin is a remarkably good absorber and emitter of infrared radiation, having an emissivity of 0.97 in the infrared spectrum. Thus, we are all nearly

(jet) black in the infrared, in spite of the obvious variations in skin color. This high infrared emissivity is why we can so easily feel radiation on our skin.

It is also the basis for the use of night scopes used by law enforcement and the military to detect human beings. Even small temperature variations

can be detected because of the T 4 dependence. Images, called thermographs, can be used medically to detect regions of abnormally high

CHAPTER 14 | HEAT AND HEAT TRANSFER METHODS 493

temperature in the body, perhaps indicative of disease. Similar techniques can be used to detect heat leaks in homes Figure 14.27, optimize

performance of blast furnaces, improve comfort levels in work environments, and even remotely map the Earth’s temperature profile.

All objects emit and absorb radiation. The net rate of heat transfer by radiation (absorption minus emission) is related to both the temperature of the

object and the temperature of its surroundings. Assuming that an object with a temperature T 1 is surrounded by an environment with uniform

temperature T 2 , the net rate of heat transfer by radiation is

Q

(14.44)

net

4

4⎞

t = σeA⎛⎝ T 2 − T 1⎠,

where e is the emissivity of the object alone. In other words, it does not matter whether the surroundings are white, gray, or black; the balance of

radiation into and out of the object depends on how well it emits and absorbs radiation. When T 2 > T 1 , the quantity Q net / t is positive; that is, the net heat transfer is from hot to cold.

Take-Home Experiment: Temperature in the Sun

Place a thermometer out in the sunshine and shield it from direct sunlight using an aluminum foil. What is the reading? Now remove the shield,

and note what the thermometer reads. Take a handkerchief soaked in nail polish remover, wrap it around the thermometer and place it in the

sunshine. What does the thermometer read?

Example 14.9 Calculate the Net Heat Transfer of a Person: Heat Transfer by Radiation

What is the rate of heat transfer by radiation, with an unclothed person standing in a dark room whose ambient temperature is 22.0ºC . The

person has a normal skin temperature of 33.0ºC and a surface area of 1.50 m2 . The emissivity of skin is 0.97 in the infrared, where the

radiation takes place.

Strategy

We can solve this by using the equation for the rate of radiative heat transfer.

Solution

Insert the temperatures values T 2 = 295 K and T 1 = 306 K , so that

Q

(14.45)

4

4⎞

t = σeA⎛⎝ T 2 − T 1⎠

= ⎛

⎡

(14.46)

⎝5.67×10−8 J/s ⋅ m2 ⋅ K 4⎞⎠(0.97)⎛⎝1.50 m2⎞⎠⎣(295 K)4 − (306 K)4⎤⎦

=

(14.47)

−99 J/s = −99 W.

Discussion

This value is a significant rate of heat transfer to the environment (note the minus sign), considering that a person at rest may produce energy at

the rate of 125 W and that conduction and convection will also be transferring energy to the environment. Indeed, we would probably expect this

person to feel cold. Clothing significantly reduces heat transfer to the environment by many methods, because clothing slows down both

conduction and convection, and has a lower emissivity (especially if it is white) than skin.

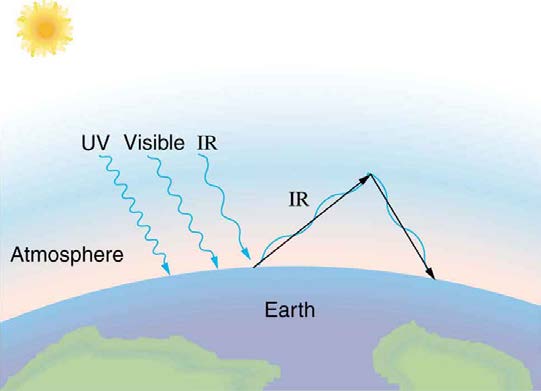

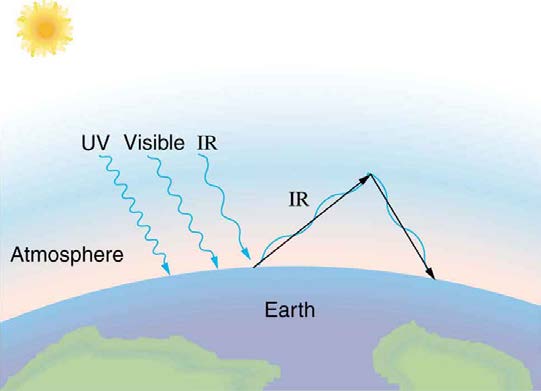

The Earth receives almost all its energy from radiation of the Sun and reflects some of it back into outer space. Because the Sun is hotter than the

Earth, the net energy flux is from the Sun to the Earth. However, the rate of energy transfer is less than the equation for the radiative heat transfer

would predict because the Sun does not fill the sky. The average emissivity ( e ) of the Earth is about 0.65, but the calculation of this value is

complicated by the fact that the highly reflective cloud coverage varies greatly from day to day. There is a negative feedback (one in which a change

produces an effect that opposes that change) between clouds and heat transfer; greater temperatures evaporate more water to form more clouds,

which reflect more radiation back into space, reducing the temperature. The often mentioned greenhouse effect is directly related to the variation of

the Earth’s emissivity with radiation type (see the figure given below). The greenhouse effect is a natural phenomenon responsible for providing

temperatures suitable for life on Earth. The Earth’s relatively constant temperature is a result of the energy balance between the incoming solar

radiation and the energy radiated from the Earth. Most of the infrared radiation emitted from the Earth is absorbed by carbon dioxide ( CO2 ) and

water ( H2 O ) in the atmosphere and then re-radiated back to the Earth or into outer space. Re-radiation back to the Earth maintains its surface

temperature about 40ºC higher than it would be if there was no atmosphere, similar to the way glass increases temperatures in a greenhouse.

494 CHAPTER 14 | HEAT AND HEAT TRANSFER METHODS

Figure 14.28 The greenhouse effect is a name given to the trapping of energy in the Earth’s atmosphere by a process similar to that used in greenhouses. The atmosphere,

like window glass, is transparent to incoming visible radiation and most of the Sun’s infrared. These wavelengths are absorbed by the Earth and re-emitted as infrared. Since

Earth’s temperature is much lower than that of the Sun, the infrared radiated by the Earth has a much longer wavelength. The atmosphere, like glass, traps these longer

infrared rays, keeping the Earth warmer than it would otherwise be. The amount of trapping depends on concentrations of trace gases like carbon dioxide, and a change in the

concentration of these gases is believed to affect the Earth’s surface temperature.

The greenhouse effect is also central to the discussion of global warming due to emission of carbon dioxide and methane (and other so-called

greenhouse gases) into the Earth’s atmosphere from industrial production and farming. Changes in global climate could lead to more intense storms,

precipitation changes (affecting agriculture), reduction in rain forest biodiversity, and rising sea levels.

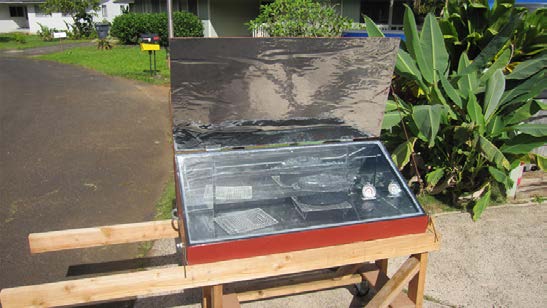

Heating and cooling are often significant contributors to energy use in individual homes. Current research efforts into developing environmentally

friendly homes quite often focus on reducing conventional heating and cooling through better building materials, strategically positioning windows to

optimize radiation gain from the Sun, and opening spaces to allow convection. It is possible to build a zero-energy house that allows for comfortable

living in most parts of the United States with hot and humid summers and cold winters.

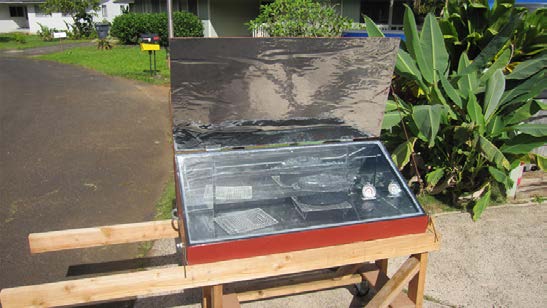

Figure 14.29 This simple but effective solar cooker uses the greenhouse effect and reflective material to trap and retain solar energy. Made of inexpensive, durable materials,

it saves money and labor, and is of particular economic value in energy-poor developing countries. (credit: E.B. Kauai)

Conversely, dark space is very cold, about 3K(−454ºF) , so that the Earth radiates energy into the dark sky. Owing to the fact that clouds have

lower emissivity than either oceans or land masses, they reflect some of the radiation back to the surface, greatly reducing heat transfer into dark

space, just as they greatly reduce heat transfer into the atmosphere during the day. The rate of heat transfer from soil and grasses can be so rapid

that frost may occur on clear summer evenings, even in warm latitudes.

Check Your Understanding

What is the change in the rate of the radiated heat by a body at the temperature T 1 = 20ºC compared to when the body is at the temperature

T 2 = 40ºC ?

Solution

The radiated heat is proportional to the fourth power of the absolute temperature. Because T 1 = 293 K and T 2 = 313 K , the rate of heat

transfer increases by about 30 percent of the original rate.

Career Connection: Energy Conservation Consultation

The cost of energy is generally believed to remain very high for the foreseeable future. Thus, passive control of heat loss in both commercial and

domestic housing will become increasingly important. Energy consultants measure and analyze the flow of energy into and out of houses and

ensure that a healthy exchange of air is maintained inside the house. The job prospects for an energy consultant are strong.

CHAPTER 14 | HEAT AND HEAT TRANSFER METHODS 495

Problem-Solving Strategies for the Methods of Heat Transfer

1. Examine the situation to determine what type of heat transfer is involved.

2. Identify the type(s) of heat transfer—conduction, convection, or radiation.

3. Identify exactly what needs to be determined in the problem (identify the unknowns). A written list is very useful.

4. Make a list of what is given or can be inferred from the problem as stated (identify the knowns).

5. Solve the appropriate equation for the quantity to be determined (the unknown).

Q

6. For conduction, equation t = kA( T 2 − T 1)

d

is appropriate. Table 14.3 lists thermal conductivities. For convection, determine the amount

of matter moved and use equation Q = mcΔ T , to calculate the heat transfer involved in the temperature change of the fluid. If a phase

change accompanies convection, equation Q = mL f or Q = mL v is appropriate to find the heat transfer involved in the phase change.

Q

Table 14.2 lists information relevant to phase change. For radiation, equation

net

4

4⎞

t = σeA⎛⎝ T 2 − T 1⎠ gives the net heat transfer rate.

7. Insert the knowns along with their units into the appropriate equation and obtain numerical solutions complete with units.

8. Check the answer to see if it is reasonable. Does it make sense?

Glossary

conduction: heat transfer through stationary matter by physical contact

convection: heat transfer by the macroscopic movement of fluid

emissivity: measure of how well an object radiates

greenhouse effect: warming of the Earth that is due to gases such as carbon dioxide and methane that absorb infrared radiation from the Earth’s

surface and reradiate it in all directions, thus sending a fraction of it back toward the surface of the Earth

heat of sublimation: the energy required to change a substance from the solid phase to the vapor phase

heat: the spontaneous transfer of energy due to a temperature difference

kilocalorie: 1 kilocalorie = 1000 calories

latent heat coefficient: a physical constant equal to the amount of heat transferred for every 1 kg of a substance during the change in phase of

the substance

mechanical equivalent of heat: the work needed to produce the same effects as heat transfer

net rate of heat transfer by radiation:

Q

is

net

4

4⎞

t = σeA⎛⎝ T 2 − T 1⎠

radiation: heat transfer which occurs when microwaves, infrared radiation, visible light, or other electromagnetic radiation is emitted or absorbed

radiation: energy transferred by electromagnetic waves directly as a result of a temperature difference

rate of conductive heat transfer: rate of heat transfer from one material to another

Stefan-Boltzmann law of radiation: Qt = σeAT 4 , where σ is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, A is the surface area of the object, T is the absolute temperature, and e is the emissivity

specific heat: the amount of heat necessary to change the temperature of 1.00 kg of a substance by 1.00 ºC

sublimation: the transition from the solid phase to the vapor phase

thermal conductivity: the property of a material’s ability to conduct heat

Section Summary

14.1 Heat

• Heat and work are the two distinct methods of energy transfer.

• Heat is energy transferred solely due to a temperature difference.

• Any energy unit can be used for heat transfer, and the most common are kilocalorie (kcal) and joule (J).

• Kilocalorie is defined to be the energy needed to change the temperature of 1.00 kg of water between 14.5ºC and 15.5ºC .

• The mechanical equivalent of this heat transfer is 1.00 kcal = 4186 J.

14.2 Temperature Change and Heat Capacity

• The transfer of heat Q that leads to a change Δ T in the temperature of a body with mass m is Q = mcΔ T , where c is the specific heat of the material. This relationship can also be considered as the definition of specific heat.

14.3 Phase Change and Latent Heat

496 CHAPTER 14 | HEAT AND HEAT TRANSFER METHODS

• Most substances can exist either in solid, liquid, and gas forms, which are referred to as “phases.”

• Phase changes occur at fixed temperatures for a given substance at a given pressure, and these temperatures are called boiling and freezing

(or melting) points.

• During phase changes, heat absorbed or released is given by:

Q = mL,

where L is the latent heat coefficient.

14.4 Heat Transfer Methods

• Heat is transferred by three different methods: conduction, convection, and radiation.

14.5 Conduction

• Heat conduction is the transfer of heat between two objects in direct contact with each other.

• The rate of heat transfer Q / t (energy per unit time) is proportional to the temperature difference T 2 − T 1 and the contact area