also plans two linear targets along the rear

matching a blocking group to both protect the

trace of the obstacle group. Team A’s FIST is

obstacles and defeat the enemy.

responsible for executing all indirect targets.

Figure 3-5 illustrates some considerations to As the enemy vehicles enter EA Gold, they

integrate fires and the block effect. The TF are still in a march formation. As the lead commander has assigned Team A the mis-enemy units pass the line defined by TRPs

sion to defend BP 5 oriented into EA Gold to

01 and 04, and the line defined by TRPs

stop an enemy battalion from advancing

04 and 02, they hit the first obstacles in

along this AA. Team A is an armor company the block-obstacle group. The company team team with two armor platoons and an AT

commander initiates volley fires from all

Obstacle Integration Principles 3-9

FM 90-7

platoons. The tank platoons in BPs 15 and 25

DEEP OPERATIONS

orient between TRPs 04 and 02 and between

Normally, commanders use situational

TRPs 01 and 04, respectively. The AT pla-

obstacles to support deep operations. In the

toon orients between TRPs 01 and 02. The

offense, they use obstacles to help interdict

tank platoons concentrate on TRPs 01 and 02

enemy reinforcements or reserves. In the

to defeat any bypass attempts where the

defense and in the retrograde, they use

obstacles tie into the impassable terrain. All

obstacles to attack enemy follow-on forma-

forces concentrate on destroying any breach-

tions or subsequent echelons. Commanders

ing assets as they move forward.

use these obstacles to support counterfire

As the enemy continues to advance, some

activities against enemy indirect-fire units.

They also use obstacles to attack enemy

breaching attempts are successful through

assets at fixed airfields or logistics sites.

the initial obstacles. The company team com-

mander emplaced obstacles in depth and

shifts fires from BP 15 to between TRPs 01

CLOSE OPERATIONS

and 03 and from BP 25 to between TRPs 03

During close operations, commanders use

and 02. The company team FIST executes

the full range of tactical and protective

group AID to help in the destruction of

obstacles. Offensive, defensive, or retrograde

breaching assets. The company team com-

operations usually require different types of

mander shifts the fires from BP 35 to concen-

obstacles.

trate on breaching equipment.

In the offense, commanders use situational

Because of the depth and complexity of the

obstacles to support the defeat of defending

obstacles, the high volume of fires destroyed

enemy forces. They attack enemy reserves or

most of the enemy’s breaching assets. The

reinforcing units with these obstacles. Com-

company team continues a high volume of

manders use them to prevent forces from

fire to defeat further breaching attempts

repositioning or to fix part of a defending

and to discourage the enemy from commit-

enemy force while massing on the remainder

ting follow-on forces along this AA.

of the force. They also use obstacles to pro-

tect the flanks of friendly units, and they

plan obstacles on the objective to support

OBSTACLES AND OPERATIONS

their transition to the defense. Reconnais-

IN DEPTH

sance and security forces use situational

obstacles to help delay or defeat enemy

Commanders use obstacles to support opera-

CATKs. During movements to contact

tions in depth. Mission analysis drives the

(MTCs), security forces use situational

need for and the types of obstacles; however,

obstacles to help fix enemy forces while the

analyzing requirements throughout the

friendly main body maneuvers into a posi-

depth of the battlefield provides some idea

tion of advantage. Commanders ensure

of how to use obstacles. Commanders consi-

that obstacles do not interfere with the

der three complementary elements when

maneuver of the reserve.

planning obstacles to support operations.

In the defense, commanders integrate all

They are—

types of obstacles to slow, canalize, and

Deep operations.

defeat the enemy’s major units. In an area

Close operations.

defense, the commander uses protective

Rear operations.

obstacles to enhance survivability. He relies

3-10 Obstacle Integration Principles

FM 90-7

on directed and reserve obstacles focused on

operations. In the offense, most protective

retaining key and decisive terrain. He may

obstacles are hasty. In the defense, deliber-

use situational obstacles to deal with unex-

ate protective obstacles are common around

pected threats or to support economy-of-

strongpoints and fixed sites. Units in BPs

force efforts. For a mobile defense, the com-

normally use hasty protective obstacles. In

mander uses directed obstacles to create the

the retrograde, units use deliberate protec-

conditions for destroying the enemy. He uses

tive obstacles around fixed sites, but hasty

situational obstacles to support CATKs and

protective obstacles are most common. Units

reserve obstacles to maintain control over

design protective obstacles specifically for

MCs. The commander tailors obstacles to

the anticipated threat. Protective-obstacle

ensure the mobility of the force.

effort is proportionate to the threat level. As

the threat level increases, the protective-

Although obstacle use in the retrograde is

obstacle effort must increase. The force may

very similar to that in the defense, reserve

employ tactical obstacles to counter any

obstacles are extremely important in the ret-

major threat to the rear operations.

rograde. Commanders focus on critical

points along high-speed AAs. The enemy is

usually attempting to advance over the same

OBSTACLE CONTROL

routes that a unit is using for the retrograde.

Obstacle control varies with echelon and

Commanders retain positive control over

METT-T. The basic idea is to limit subordi-

these routes with reserve obstacles.

nates only as necessary to synchronize their

In the defense or retrograde, security forces

obstacle efforts with the commander’s intent

use different reinforcing obstacles depending

and scheme of maneuver. A lack of obstacle

on the security force mission. Requirements

control can cause obstacles to interfere with

for reinforcing obstacles increase from the

the higher commander’s scheme of maneu-

screen to guard and cover missions. A

ver. Too much obstacle control can cause a

lack of obstacles that support the refined

screening force uses directed and situational

fire plans of subordinate commanders.

obstacles to help harass and impede the

enemy or to assist in its displacement. A

To provide obstacle control, commanders

guard force uses all types of tactical obsta-

focus or withhold obstacle-emplacement

cles to assist in the delay. It may use hasty

authority or restrict obstacles. They use

protective obstacles for protection against

obstacle-control measures, orders, or other

the enemy’s assault. A covering force not

specific guidance. Commanders and staffs

only attacks, defends, and delays but also

consider width, depth, and time when they

deceives the enemy regarding the location,

conduct obstacle-control planning. The fol-

size, and strength of forces in the main bat-

lowing concepts guide this planning:

tle area (MBA). The covering force employs

Support current operations.

obstacles to a greater extent than the guard

Maximize subordinate flexibility.

force. The number of obstacles must resem-

Facilitate future operations.

ble the number in the MBA to support the

deception of the location of the MBA.

SUPPORT CURRENT OPERATIONS

Commanders and staffs use obstacle control

REAR OPERATIONS

to focus obstacle effort where it will clearly

Protective obstacles are the primary rein-

support the scheme of maneuver and com-

forcing obstacle employed in support of rear

mander’s intent. They also plan obstacle

Obstacle Integration Principles 3-11

FM 90-7

control to ensure that obstacles will not

wants a brigade to defend well forward. The

interfere with current operations.

commander gives the brigade an obstacle

zone that includes only the forward part of

its sector. The division commander thus

MAXIMIZE SUBORDINATE FLEXIBILITY

ensures that any obstacles the brigade

Commanders normally give subordinates

emplaces will support a defense forward in

flexibility to employ obstacles similar to the

the sector.

flexibility to conduct tactical missions. For

example, defending in sector requires flexi-

Other specific guidance or orders provide a

bility in obstacle employment. A com-

means to focus obstacle-emplacement

mander will give subordinates maximum

authority. For example, a corps commander

emplacement authority to support the

may include in his OPORD instructions for a

defender’s freedom to maneuver and decen-

division to concentrate obstacle effort along

tralized fire planning. A commander will

a specific enemy AA. A second example is a

probably focus obstacle-emplacement

brigade commander that wants a TF to force

the enemy into an adjacent TF sector. The

authority for a unit defending from a BP.

Defending from a BP requires more obstacle

brigade commander gives the TF an obstacle

control because the BP dictates the

belt that encompasses most of the TF sector,

defender’s position and orientation of fires.

but he assigns an intent (target, obstacle

In the offense, commanders normally retain

effect, and relative location) to the belt. The

a higher degree of control due to limited

target helps to focus the type of obstacles the

opportunities for obstacle emplacement and

subordinate will choose. The effect (here it is

more requirements for friendly mobility.

to turn the enemy into the adjacent TF sec-

Commanders frequently withhold emplace-

tor) helps focus the obstacle array. The rela-

ment authority or restrict the use of most

tive location, within the belt, still allows the

obstacles.

TF commander maximum flexibility to

develop his own scheme of maneuver and

obstacle plan.

FACILITATE FUTURE OPERATIONS

Commanders withhold obstacle-emplace-

The need for future mobility drives the need

ment authority using control measures,

for obstacle control to facilitate future opera-

orders, or other specific guidance. For exam-

tions. A CATK axis and objective are exam-

ple, a commander withholds authority by

ples of future mobility needs. Another

shaping obstacle-control measures so that

example is a route for units that need to

they do not overlap the CATK axis and

reposition forward as part of a higher com-

objective, ensuring the freedom of the CATK

mander’s plan. Commanders usually with-

force.

hold emplacement authority or use

Obstacle restrictions are an important tool

restrictions to ensure that obstacles do not

for providing obstacle control. For example,

interfere with future maneuver; however,

a corps commander may designate a CATK

they may focus obstacle efforts to develop a

axis, through a division AO, as an obstacle

situation that will support future opera-

restricted area. A division commander

tions.

may restrict obstacles in objectives and

Commanders can focus obstacle-emplace-

planned BPs within the division sector to

ment authority using obstacle-control mea-

SCATMINEs with a not later than (NLT)

sures. For example, a division commander

SD time.

3-12 Obstacle Integration Principles

FM 90-7

The commander considers the following

emplace and integrate the directed obstacles

dimensions when planning obstacle control:

in the TF obstacle groups.

Width.

The echelonment of obstacle planning

Depth.

requires that commanders at each level pro-

Time.

vide subordinates with the right combina-

Maneuver control measures can aid in

tion of positive control and flexibility. At

tailoring the width and depth of obstacle-

each level, obstacle planning builds on the

control measures. Typical graphics that aid

obstacle plan from higher echelons. Without

in focusing the width and depth of obstacle-

obstacle zones and belts, units must submit

control measures are—

a report of intention (see Appendix B) for every obstacle. The report doubles as a

Unit boundaries and phase lines (PLs).

request when units initiate it at levels below

Battle handover lines (BHLs) and for-

emplacement authority. Units do not submit

ward edges of the battle area (FEBAs).

the report if the higher HQ grants emplace-

Lines of departure (LDs) and lines of

ment authority. Commanders give the

contact (LCs).

authorization to install obstacles when they

Fire-support coordination lines

establish obstacle-control measures. As an

(FSCLs), no-fire areas (NFAs), and

exception, units do not submit reports of

coordinated fire lines (CFLS).

intention for conventional obstacles that are

Passage lanes and corridors.

part of an operation plan (OPLAN) or gen-

CATK axis and movement routes.

eral defense plan (GDP) if the authorizing

Objectives, future BPs, and AAs.

commander approves the plan.

Commanders also consider time when plan-

ning obstacle control. For example, the use

CORPS-LEVEL PLANNING

of an on-order obstacle zone gives the com-

Corps-level obstacle planning primarily

mander the ability to give a subordinate

centers on obstacle control. The corps devel-

obstacle-emplacement authority only after a

ops obstacle restrictions to ensure that divi-

certain time or event. Also, the use of mines

sion obstacles do not interfere with the

with a SD time within a control measure

corps’ scheme of maneuver and future oper-

allows a commander to limit the time that

ations. The corps also provides obstacle-

obstacles affect an area.

emplacement authority to ACRs and sepa-

rate brigades using obstacle zones; however,

they do not provide obstacle-emplacement

ECHELONS OF OBSTACLE

authority to divisions. Divisions already

PLANNING

have the authority to emplace conventional

The nature of obstacle integration from

obstacles within their AOs. The corps plans

corps to company team leads to an echelon-

reserve or situational obstacle groups only

ment of obstacle planning. At each lower

as they are necessary to support the corps’

level, commanders and staffs conduct more

scheme of maneuver. In very rare instances,

detailed planning. At corps level, planning

the corps may plan directed obstacle groups.

mainly consists of planning obstacle restric-

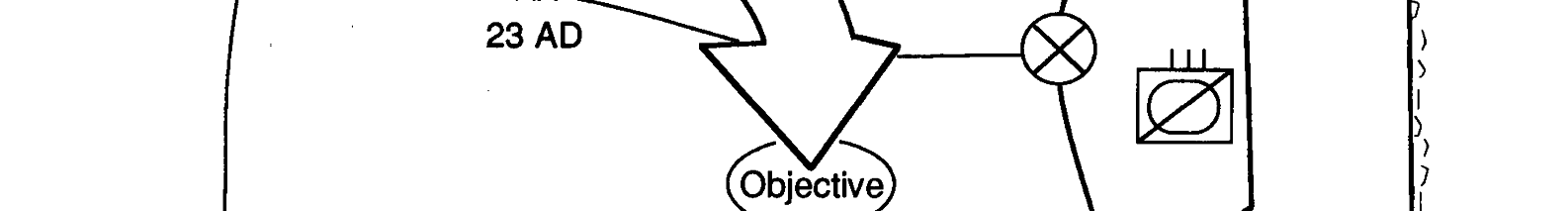

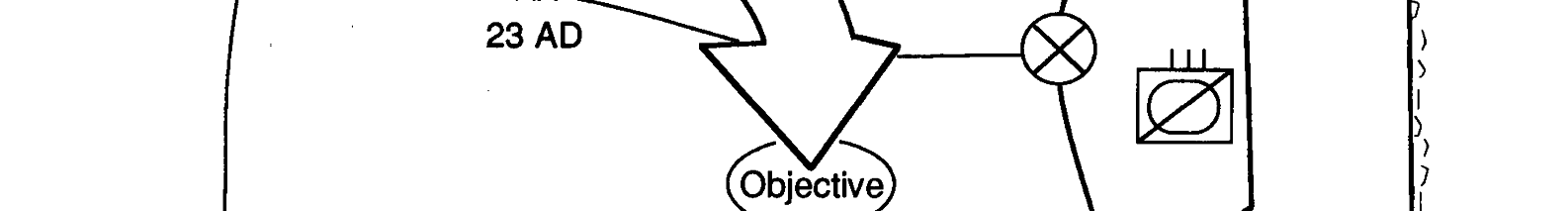

Figure 3-6, page 3-14, shows a corps defend-tions, although the corps may plan reserve,

ing with two divisions on line, an ACR as a

situational, or directed obstacle groups. At

covering force, and a separate brigade in

the company-team level, planning consists of

reserve. The corps plans a zone in the

the detailed design and siting plans to

ACR covering force area to provide the ACR

Obstacle Integration Principles 3-13

FM 90-7

commander with obstacle-emplacement

that brigade obstacles do not interfere with

authority and to focus the ACR obstacle

corps- or division-level operations. Divisions

effort close to the forward line of own troops

plan reserve and situational obstacle groups

(FLOT). Because the corps commander

to support the division’s and corps’ scheme of

wants to allow the ACR commander flexibil-

maneuver. Again, the planning of directed

ity, he does not assign a specific obstacle

obstacle groups is rare.

effect to the zone. To ensure that the corps

CATK is not hindered by obstacles, the com-

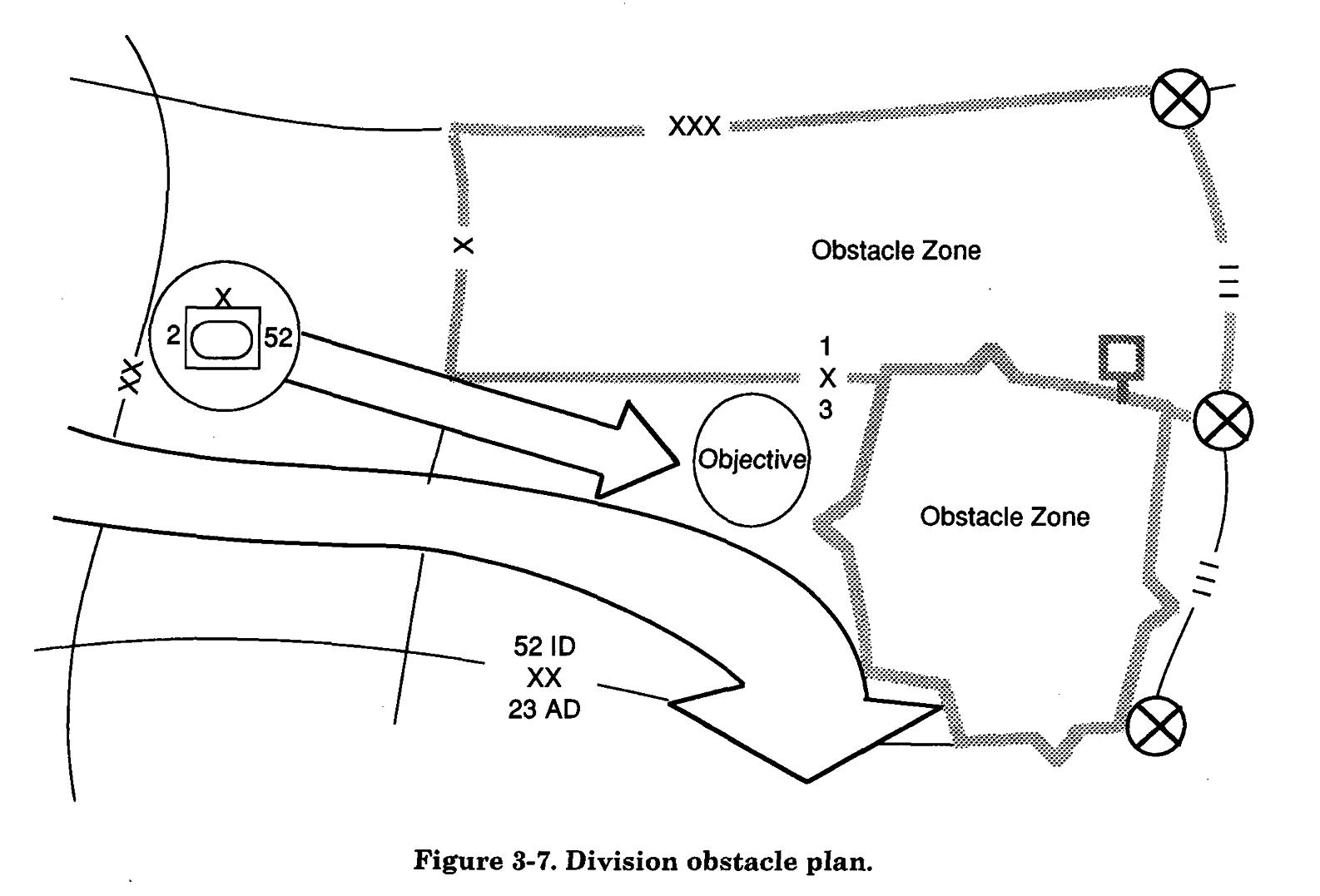

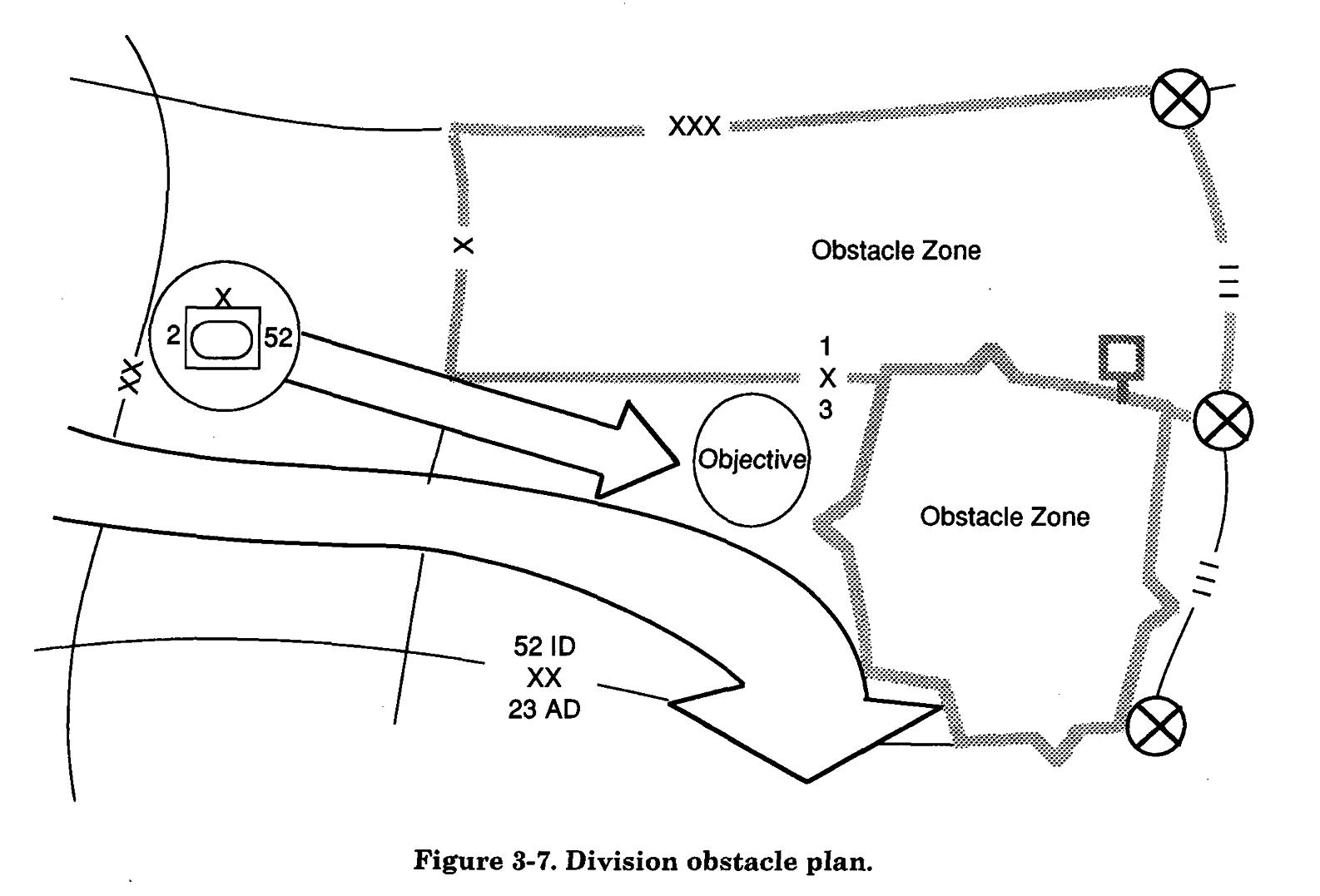

In Figure 3-7, the 52d Infantry Division (ID)

mander designates in the OPORD that the

(mechanized) of the defending corps con-

corps CATK axis is an obstacle restricted

ducts its defense with two brigades on

area, with no obstacles allowed.

line and a brigade in reserve. The division

plans a zone well forward in 3d Brigade’s

sector and targeted at an enemy division AA.

DIVISION-LEVEL PLANNING

This constrains the brigade’s obstacle-

At the division level, obstacle planning is

emplacement authority and ensures that its

more directive than at corps level. Divisions

obstacles do not interfere with the corps’ or

concentrate on planning obstacle zones to

division’s CATK routes. Note that the divi-

give brigades and other major subunits

sion does not need to designate either

(such as a cavalry squadron) obstacle-

CATK axis as an obstacle restricted area.

emplacement authority. Divisions also use

No one who is subordinate to the division

restrictions with the obstacle zones to ensure

has authority to emplace obstacles in these

3-14 Obstacle Integration Principles

FM 90-7

areas. In the north, the division designates

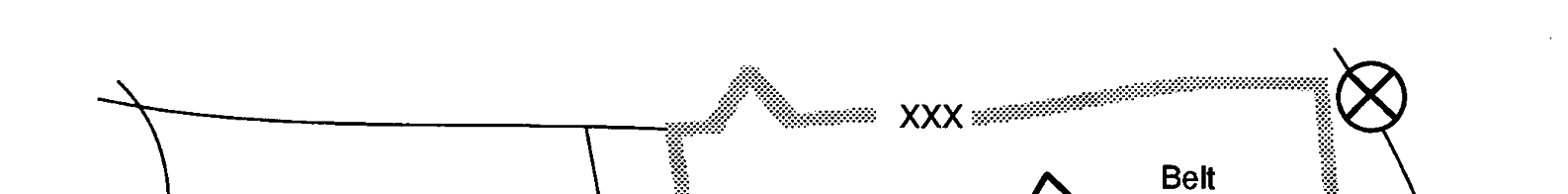

Based on his analysis of METT-T, the 1st

the entire 1st Brigade sector as a zone, tar-

Brigade commander of the 52d ID decides

geted at an enemy division; therefore, no

to defend as shown in Figure 3-8, page

additional graphic is required. However, the

3-16. He has positioned TF 4-27 in a BP and division has designated a contact point on

has assigned it responsibility for a block

the brigades’ boundaries and has directed

obstacle belt to defeat a second echelon

them to coordinate obstacles on the ground.

enemy regiment. TF 2-27 has responsibility

for a fix obstacle belt in the north to destroy

BRIGADE-LEVEL PLANNING

an enemy first echelon regiment. In the

Brigade-level units conduct more detailed

south, the commander assigns TF 1-93 a

obstacle planning. Brigades plan obstacle

turn obstacle belt, positioned well forward

belts that give obstacle-emplacement

in the sector to prevent an enemy regiment

authority to TFs. Brigades also use obstacle

from advancing along the boundary with

restrictions. Frequently, they plan situa-

the 3d Brigade. Note that the commander

tional obstacle groups and reserve obstacle

has specified an effect for each belt. Also,

groups. Directed obstacle group planning is

the commander has designated a contact

more common than at division level; how-

point between the two TFs to facilitate

ever, it is still rare.

obstacle coordination.

Obstacle Integration Principles 3-15

FM 90-7

TASK-FORCE-LEVEL PLANNING

COMPANY-TEAM-LEVEL PLANNING

TFs conduct the majority of detailed obstacle

At the company team level, obstacle plan-

planning. They plan most obstacle groups

ning focuses on the detailed design and sit-

that are executed at the company team level.

ing plans to execute the directed,

Most of these obstacle groups are directed

situational, and reserve obstacle groups

obstacles, but TFs can also plan reserve and

planned at higher levels.

situational obstacles. TFs may use restric-

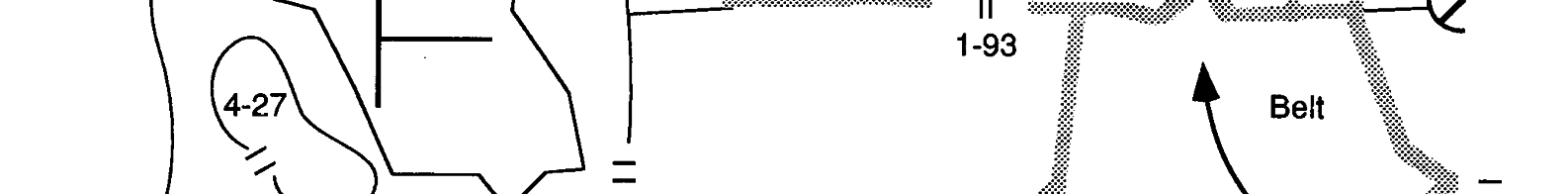

Figure 3-10 shows the obstacles Team A

tions, but normally do not because of the level

designed and sited to support the obstacle

of detail of the TF obstacle plan.

group intent. Note that the obstacles are in

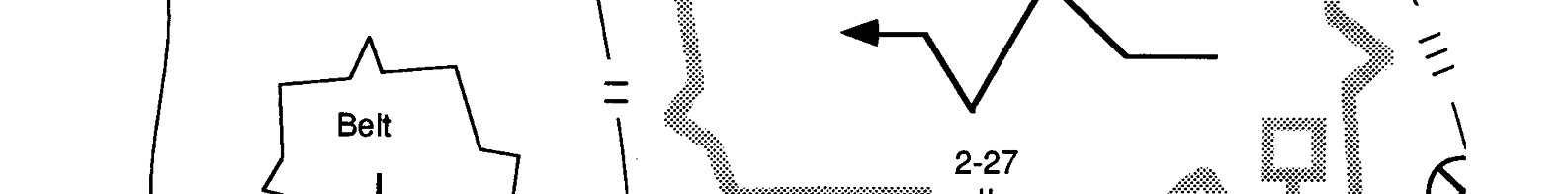

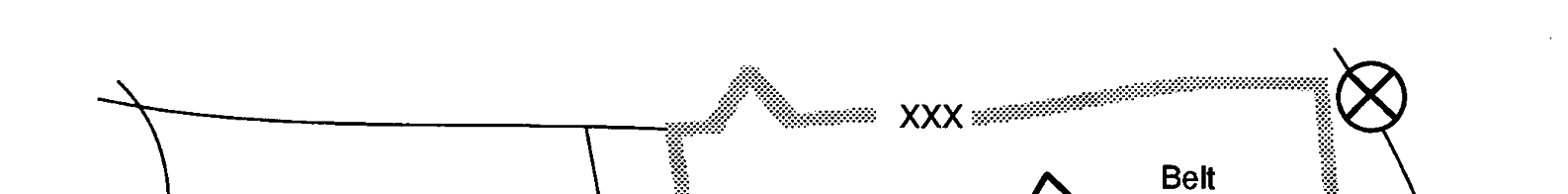

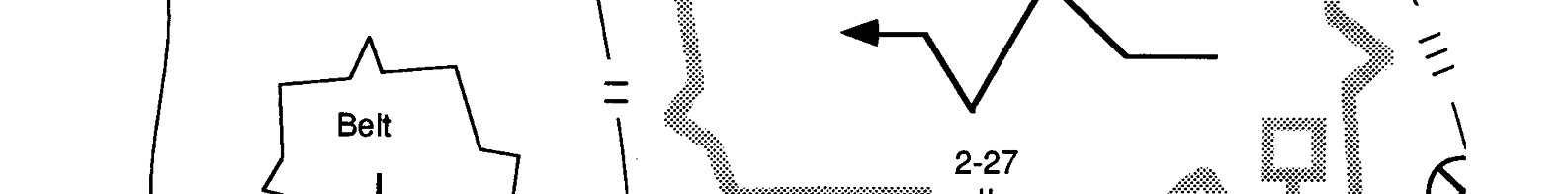

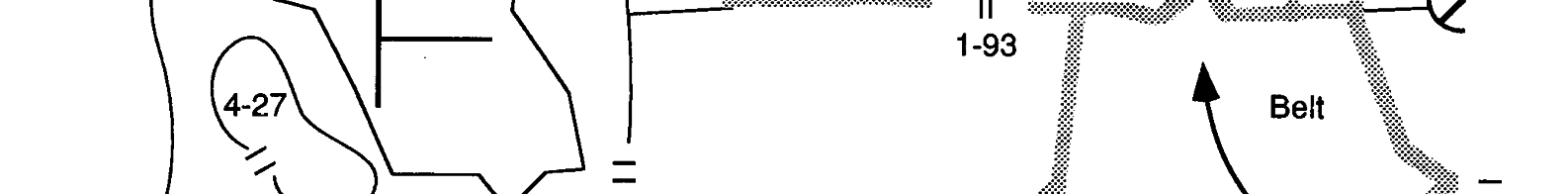

TF 1-93 plans to defend as shown in Fig-

depth and tied into terrain. The company

ure 3-9 and plans