INTRODUCTION

DURING THE HOLOCAUST, APPROXIMATELY SIX MILLION JEWS AND COUNTLESS OTHER MINORITIES

were murdered by the Nazis and their collaborators. Between the German invasion of the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941 and the end of the war in Europe in May 1945, Nazi Germany and its accomplices strove to murder every Jew under their domination. Driven by a racist ideology that considered Jews and other minorities to be inferior to the “superior” German people, the Nazis set out to subjugate and later, eliminate them.

The killing began with shootings and evolved to murder by gas. Because Nazi discrimination against the Jews began with Hitler’s accession to power in January 1933, many historians consider this the start of the Holocaust era. The Jews were not the only victims of Hitler’s regime, but they were the only group that the Nazis sought to destroy entirely. This genocide of the Jews resulted in the murder of two-thirds of European Jewry.

Numerous people fell victim to the Nazi regime

for political, social, or racial reasons. Germans were among the first victims persecuted because of their

political activities. Many died in concentration camps, but most were released after their spirit was broken.

Germans who suffered from mental or physical handi-

caps were killed under a “euthanasia” program. Oth-

er Germans were incarcerated for being homosexuals,

criminals, or nonconformists; these people, although

treated brutally, were never slated for utter annihilation as were the Jews.

ashem

ad V

Roma and Sinti were murdered by the Nazis in

© Y

large numbers. Estimates range from 200,000 to over Two women say goodbye as Jews are rounded up before depor-500,000 victims. Nazi policy toward Roma and Sinti tation in Lodz, Poland.

was inconsistent.1 In Greater Germany, Roma and Sin-

ti who had integrated into society were seen as socially dangerous and eventually were murdered, whereas in the occupied Soviet Union, Roma and Sinti who had integrated into society were not persecuted, but those who retained a nomadic lifestyle were put to death.

The Slavic People of Belarus, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Russia, Ukraine and Yugoslavia were also deemed racially inferior by the Nazis. As such, they were discriminated against, imprisoned and murdered as Hitler attempted to reorganize Europe on racial grounds.

This study guide provides an important educational tool for understanding one group’s experience during the Holocaust, that of women. Each chapter reveals a particular struggle that women faced and how they dealt with it, from caring for their families when deprived of basic needs to trying their hardest to maintain some sense of purpose, humanity and strength, when all hope appeared to be lost. The companion DVD contains the personal stories of six women who lived through this period and experienced the Holocaust in different ways.

What makes the study of women and the Holocaust so important? What can we gain from studying it? Today, there is a broader and deeper perspective of research, which now includes the comparison of the female experience in the Holocaust to that of men in physical, psychological and social terms.

Women and the Holocaust: Courage and Compassion

7

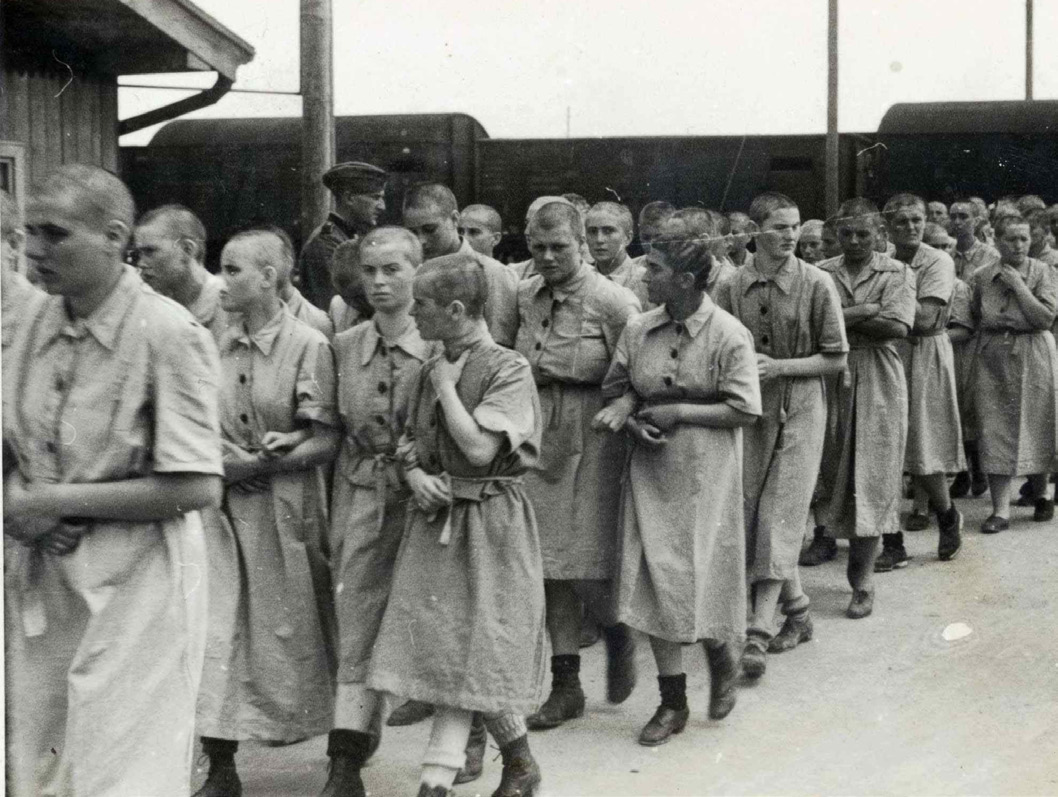

While not physically equipped, women were required to perform hard labour, which, along with malnutrition and stress, had an adverse effect on their ability to conceive and care for their children.

The psychological effects of such extraordinary circumstances came in the form of depression over the loss of their families, hope for rescue, and as a result of being deprived of their womanhood and femininity. Women also experienced anxiety over the fate of their children, and feared sexual abuse and rape.

Socially, women still attempted to create a home-like environment and provide some nor-malcy amidst the uncertainty of the daily life. Crowded into ghettos or deported, often separated from the men, they had to adapt. Despite the extreme situation, these women showed determination, leadership, compassion, dedication, courage and the willpower to survive.

ENDNOTES

1

The Holocaust Resource Center, Yad Vashem, The Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority, http://www.yad.vashem.org .

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. What was Nazi racist ideology?

2. Which groups were targeted by the Nazis for discrimination, imprisonment or murder?

3. What does study about women during the Holocaust tell us?

4. How can we combat racism, xenophobia and anti-Semitism in our world today?

Women and the Holocaust: Courage and Compassion

8

A woman with a baby

begging in the ghetto,

Warsaw, Poland, 1941.

© Yad Vashem

Women and the Holocaust: Courage and Compassion

9

CHAPTER I : DETERMINATION

Emanuel Ringelblum, the historian who documented the Warsaw ghetto, wrote in his diary: “...The future historian will have to dedicate an appropriate page to the Jewish woman in the war. She will take up an important page in Jewish history for her courage and steadfastness. By her merit, thousands of families have managed to surmount the terror of the times”.1

To paraphrase Ringelblum, one of the important pages of history on the Jewish woman in the Holocaust should relate to her heroic role within the family unit. Irrespective of whether the family was Orthodox or secular, rich or poor, large or small, the Holocaust caused radical changes in familial daily life. The traditional roles within the Jewish family shifted, as it suffered from hunger, terror, fear, and murder by the Nazis. As part of life in the ghettos – as well as that in hiding, in the forest, in transit camps, or elsewhere – Jewish women, primarily mothers, were forced into a daily struggle for survival. This struggle principally revolved around

assuring food supply, work, maintaining hygiene to

prevent disease, and a desperate, stubborn attempt

to keep family members alive. These changes caused

an upheaval in the traditional gender roles, in which women took on new roles, and were forced to face

extreme situations they had not previously encoun-

ashem

tered.

ad V

© Y

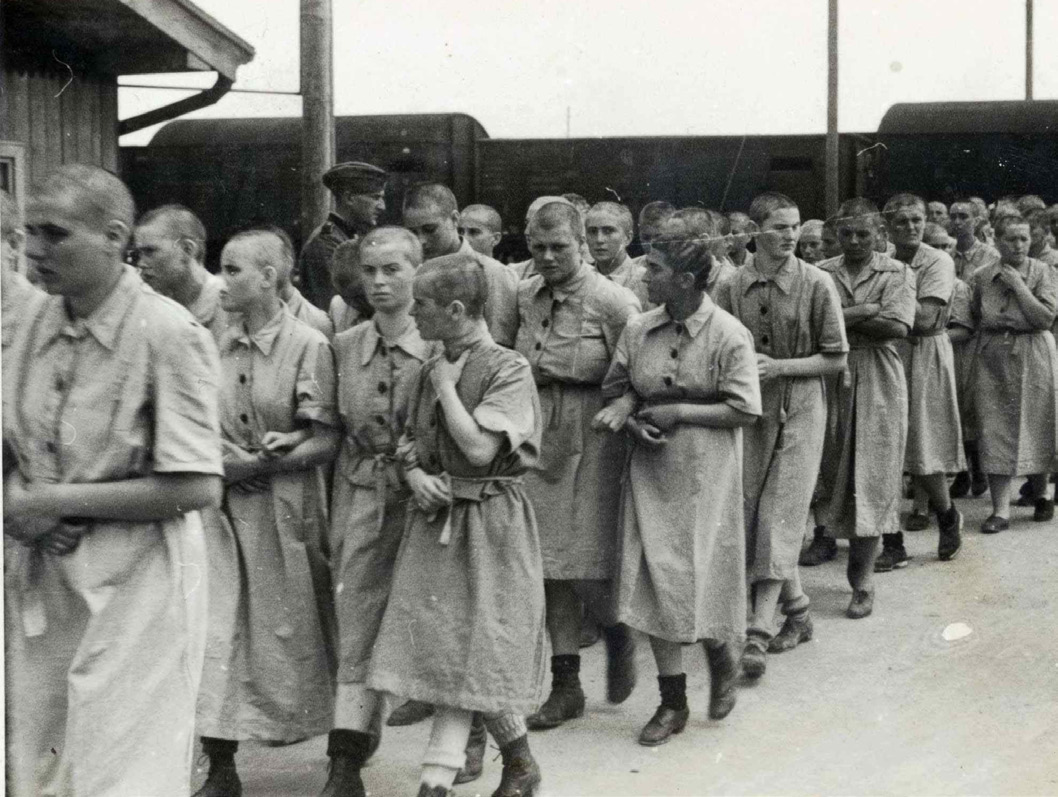

The continued deterioration in the women’s liv- Upon selection for forced labour at Auschwitz Birkenau, the wom-ing conditions, the escape eastward of men in con- en suffered further humiliation by having their heads shaved.

quered Poland, their random recruitment to forced

labor – and thus their fear to go out onto the street – caused an expansion in the women’s sphere of operation, and increased their influence within the family. As a result, women were the first to be forced to deal with a range of hardships and difficulties. One sphere was the problem of hunger. In ghettos and in hiding places, where Jews still maintained a family unit, the family members endured terrible hunger. Some women and girls risked their lives to smuggle food. Mothers were forced to contend with pitifully small ration quotas, and thus face the dilemma of how to divide food among the family members. Many mothers withheld food from themselves in order to try and protect their children. Forced to work, they suffered great anxiety while the children were often left home alone, under constant threat of house raids.

Jewish women and mothers tried stubbornly to preserve hygiene, under impossible circumstances, in order to prevent often fatal diseases. They protected and helped their sick children, even when they themselves were ill. They did their best to represent or defend their men when necessary and at times stood defiant against the Nazis at great personal risk. Hana Abrotsky (born in Warsaw, Poland, in 1932): “In the ghetto, Mother revealed herself in all her resourcefulness. Mother – who before the war I had never seen in the kitchen, who had never cleaned, laundered, scrubbed or washed dishes with her bare hands – maintained our apartment’s cleanliness with gritting teeth and at great personal risk” .2

Women and the Holocaust: Courage and Compassion

10

The Holocaust was a cataclysmic event for Jewish and Roma and Sinti families, and most did not survive roundups, incarceration, deportation and the camps. The ability of the women to adapt, their capacity to improvise, and their bravery are some of the remarkable phenomena of the Holocaust.

Irena Liebman (born in Lodz, Poland, in 1925), wrote in testimony submitted to Yad Vashem: “From what magical stream does my mother draw strength for all of this? There must be some great, hidden force, a force of love, a force of tremendous will to hold on and watch out for us”.3

ENDNOTES

1

Emmanuel Ringelblum, Notes from the Warsaw Ghetto, The Journal of Emmanuel Ringelblum, ed. and trans. Jacob Sloan, (New York: Schocken Paperback, 1974).

2

Hana Abrotsky, A Star among Crosses (Tel Aviv, 1995) 96-97 [Hebrew].

3

Irena Liebman Testimony, Yad Vashem Archives, O.3/3752.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. What were some of the problems women had to contend with in their daily struggle for survival?

2. How did mothers help their families to survive in the ghettos?

3. In what ways did the traditional roles of women change during the Holocaust?

4. How did women find the strength to deal with such difficult circumstances?

Women and the Holocaust: Courage and Compassion

11

Jewish women and girls

are washing laundry in

a concentration camp in

France.

© Yad Vashem

Women and the Holocaust: Courage and Compassion

12

CHAPTER II : LEADERSHIP

Blessed is the match consumed in kindling flame.

Blessed is the flame that burns in the secret fastness of the heart.

Blessed is the heart with strength to stop its beating for honour’s sake.

Blessed is the match consumed in kindling flame.

— HANNAH SZENES

This poem was written by Hannah Szenes, 23, a Hungarian Jew and a member of a group of para-chutists who were sent from Palestine on rescue missions to Nazi-occupied Europe. Although the chance of success was small, she felt that the group would be an inspiring and morale-raising symbol of hope for the Jews of Europe. Hannah was captured by the Nazis upon crossing the border into Hungary in 1944, tortured and later executed by firing squad.

Hannah was one woman among many who assumed leadership roles that were traditionally occupied by men. These women inspired their communities and provided strength and hope at a time when it was most needed. They headed community

and social groups; they ran soup kitchens and day care centres for children; and they provided relief from the day’s hardships for men, women and children.

Cecila Slepak was a journalist and translator who

lived in Warsaw before the war. Emanuel Ringelblum,

founder of the archive “Oneg Shabbat”, commis-

sioned Slepak to conduct research on Jewish women

living in the Warsaw ghetto. Held during the winter

and spring of 1942, Slepak’s interviews provide a

ashem

unique description of women’s strategies for coping

ad V

with the increased dangers that they were facing and

© Y

their shifting patterns of accommodation, defiance Rachel Rudnitzki joined a group of partisans that operated in Rudniki forest, Lithuania.

and resistance.

While very few women were able to join the ranks of the decision-makers in the ghetto, Gisi Fleischmann was accepted as a member of the male-dominated Judenrat in Slovakia. The Judenrat was a Jewish council set up in the ghettos by the Nazis to ensure that their orders and regulations were carried out. According to Professor Yehuda Bauer, a historian of the Holocaust, Gisi headed an underground group in the Slovak Judenrat and she was involved in efforts to get as many Jews as possible out of Slovakia. Professor Bauer indicated in his book, Rethinking the Holocaust, that the documentation shows that it was precisely because of her qualities as a woman, along with her strong personality, commitment, and wisdom, that the men accepted her leadership1.

Another woman who was involved in Judenrat operations was Dr. Rosa Szabad-Gabronska, a physician, who became a member of the Vilna Judenrat upon entering the ghetto. In this capacity she coordinated the care of young children, and at her initiative, a day-care centre was established, where children were fed, received medical aid, and played until their parents returned from work. Dr.

Szabad-Gabronska also opened a special centre for the distribution of milk for young children, and a centre for orphans. Dr. Szabad-Gabronska was murdered in Majdanek, a concentration and death camp in Nazi-occupied Poland.

Women and the Holocaust: Courage and Compassion

13

Women also led efforts to organize cultural activities whenever possible to lift spirits and foster a sense of community. At this time of darkness, there was an extraordinary need for some signs of nor-malcy, such as art, music and dramatic performances that provided relief from the persistent anxiety and despair. Vava Schoenova (Nava Schaan) was a famous theatre actress in Prague before the war. In July 1942, she was deported to the Terezin ghetto where she continued to perform, direct, and create theatre for children and youth. A woman survivor of Terezin told Schaan years later: “I owe you my childhood. …When I was your ‘firefly,’ this became my best childhood memory: to run around the stage and sing ‘the Spring will come.’ It was for me more than you can imagine. You created there, under the difficult conditions, great moments for the children”.2

ENDNOTES

1 Yehuda Bauer, Rethinking the Holocaust (New Haven,CT: Yale University Press, 2001).

2 Nava Schaan, To be an Actress, Trans. Michelle Fram Cohen (Lanham, MD: Hamilton Books, 2010).

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. Why could Hannah Szenes be considered a leader in her day?

2. Why are Cecilia Lepak’s interviews with the women of the Warsaw ghetto so important today?

3. What was significant about the participation of a woman in the Judenrat?

4. In what other ways did women serve as leaders in their communities?

Women and the Holocaust: Courage and Compassion

14

The title of Righteous

Among the Nations was

posthumously bestowed

upon Elisabeth Hedwig

Leja for saving Jewish

children during the war.

© Yad Vashem

Women and the Holocaust: Courage and Compassion

15

CHAPTER III : COMPASSION

“Whosoever saves a single life, saves an entire universe”.

(MISHNAH, SANHEDRIN 4:5)

Attitudes towards the Jews during the Holocaust mostly ranged from indifference to hostility. Most people watched as their former neighbors were rounded up and killed; some collaborated with the perpetrators; many benefited from the expropriation of the Jews property. Yet in a world of total moral collapse there was a small minority who mustered extraordinary compassion to uphold human values. These were the Righteous Among the Nations. More than half of them were women.

Righteous Among the Nations is an official title awarded by Yad Vashem, The Holocaust Martyrs’

and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority, on behalf of the State of Israel and the Jewish people to non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. The title is awarded by a special commission headed by a Supreme Court Justice according

to a well-defined set of criteria and regulations.

The price that rescuers had to pay for their action

differed from incarceration in the camps to execution.

Notices warning the population against helping the

Jews were posted everywhere. Many of those who

decided to shelter Jews had to sacrifice their normal lives and to embark upon a clandestine existence – in fear of their neighbors and friends – and to accept a life ruled by dread of denunciation and capture.

ashem

Most rescuers were ordinary people. Some acted

ad V

out of political, ideological or religious convictions;

© Y

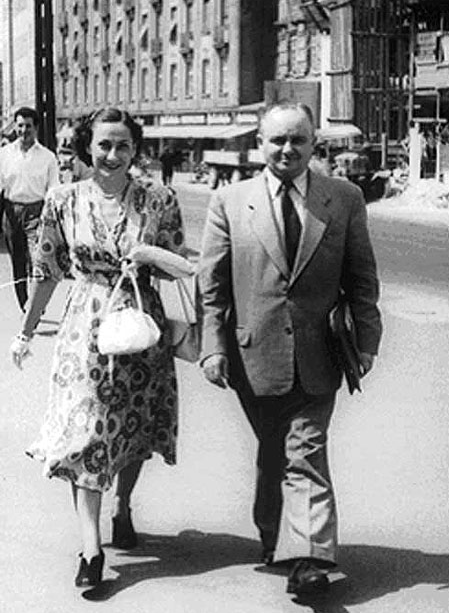

others were not idealists, but merely human beings After the war’s end, Bergen Belsen became the largest Displaced Persons (DP) camp in Europe, with 10,000 inhabitants in 1946.

who cared about the people around them. In many

cases they never planned to become rescuers and

were totally unprepared for the moment in which they had to make such a far-reaching decision.

They were ordinary human beings, and it is precisely their humanity that touches us and should serve as a model.

Elisabeth Hedwig Leja, was one of these rare people.

Edward and Dora Gessler, a Jewish couple, lived with their children, in the city of Beilsko Biala in Southern Poland. In 1938, Elisabeth Hedwig Leja, a Polish Catholic woman of ethnic German origin joined the family as a nanny of the family’s three young children, Elek, 11, Lili, 4, and Roman, 1. At the outbreak of the war, rather than join her family in safety, Elisabeth chose to remain with the Gesslers and help them as they fled from Beilsko Biala to Lvov. In Lvov, Dora, unable to bear the strain, committed suicide. Elisabeth remained to assist Edward, now a widower with three young children.

Towards the end of 1941, Edward and his son Elek escaped to Hungary. Lili and Roman remained in the care of Elisabeth. Several months later in March 1942, fearing for their lives, Elisabeth, Lili and Women and the Holocaust: Courage and Compassion

16

Roman fled Lvov, and journeyed to Hungary via the Carpathian Mountains to join Edward and Elek.

Elisabeth sewed her meager valuables into the lining of young Roman’s coat, and hired a rickety cart and two guides to take them through the mountains. As darkness approached, the group was stopped by the Gestapo. Elisabeth, with her native German, successfully convinced the officers that she was hurrying to find a doctor for her sick children. Elisabeth went to great lengths to protect the children, even dying Lili’s hair lighter and teaching them Christian customs, at real risk to her own life.

Eventually they were reunited with Edward and Elek in Budapest. Separated again when Elisabeth and Edward were arrested in 1944 and sent to a concentration camp, the family eventually was able to flee to Romania.

On 11 October 2007, the title of Righteous Among the Nations was posthumously bestowed upon Elisabeth Hedwig Leja Gessler.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. Who is a “Righteous Among the Nations”?

2. What could have motivated people to rescue their neighbours or people they did not even know when punishment for this could have been death?

3. Why do you think more people did not try to help those persecuted by the Nazis?

4. Why is the story of Elizabeth Hedwig Leja so unique?

Women and the Holocaust: Courage and Compassion

17

Yulichka Stern and her

son were both murdered

in Auschwitz Birkenau

in 1944.

© Yad Vashem

Women and the Holocaust: Courage and Compassion

18

CHAPTER IV : DEDICATION

Women are identified with caring for others. The origins of this identification lie in the perception of women as those responsible for care of the family and others. During the Holocaust, women were thus relied upon as caregivers, dedicated to helping family and friends stay alive.

Prior to the Holocaust, women discharged a range of functions. They helped to support the house-hold, sometimes even as sole breadwinners. They assumed roles that required academic training, such as doctors and nurses, social workers and university lecturers. Most working women, however, were kindergarten teachers, schoolteachers, shopkeepers, childcare providers, cooks, seamstresses and the like. Few women had economic power and none, to be

sure, were among the leaders of European Jewry.

This behaviour pattern persisted during the Holo-

caust; one may even say that it expanded. Almost all

women had to work, either to support their families

or in German factories under Nazi duress. During the

ghetto period, women accepted miscellaneous jobs that came their way, but many sought public functions that involved helping and caring for others.

Some had performed such tasks before the Holocaust

as well, but many others utilized the skills they had ac-quired as housewives and extended them to community

ashem

activity. Women managed soup kitchens, ran children’s ad V

homes, and built networks for care of the elderly. They

© Y

Jewish refugee children from Germany before setting sail for served as teachers and caregivers for children whose par- Harwich, England.

ents had been deported or mobilized for forced labour.

Women cared for other women who were no longer able to care for themselves and their families.

They worked as doctors and nurses in the ghettos, with the partisans, and in the camps.

One of the initial dilemmas that the family faced was how to find a hiding place, especially for the children, while it was still possible. Arranging a hiding place for a child was a complicated, expensive, and relatively uncommon process. Parents could not marshal the psychological will to take such a step, knowing that they would never see their child again, unless they sensed that the alternative was death. Since such an insight was difficult to internalize, many parents did not surrender their children to others even when they could have done so. Some Jewish parents, however, recognized the immi-nent danger posed by Hitler before the war and were able to send their children on the Kindertrans-port to Great Britain, where some 10,000 Jewish children lived in safety with British families.

Amidst all this violent terror, women found the mental fortitude to continue loving their children, caring for them until the moment of death and making decisions about their fate that people until that time had never had to confront. Some mothers elected to die with their children even though they could have chosen differently. Rabbi Israel Meier Lau was given away by his mother moments before he was to be placed aboard the train together with her. He wrote: “Separation from one’s mother is an inconceivable thing; its agony grips all corners of the psyche for all the years of one’s life. It took me some time to realize that by shoving me toward Naphtali [his brother], Mother had saved my life”.1

Women and the Holocaust: Courage and Compassion

19

At a certain point, some who had lost their families, found some consolation in caring for others.

They risked their lives and health by treating contagious patients and children in hiding places. Many went to their death with the children although they could have been saved. They toiled from morning to night as the situation deteriorated with each passing moment, not allowing their physical weak-ness to abate their efforts. Stefania Wilczynska was Dr. Janusz Korczak’s deputy. Together they ran the Warsaw Jewish orphanage. In a letter sent to her friends in Palestine, she wrote: “My dear, we are well. I work a little at the orphanage while Korczak is doing a great deal. I have not arrived because I do not want to go without the children”.2 Wilczynska and Korczak were given a choice not to join the children’s deportation, but they refused, and went together with them to the gas chambers.

ENDNOTES

1

Rabbi Israel Meir Lau, Do Not Raise Your Hand Against the Boy (Tel Aviv-Jaffa, Israel: Miskal - Yedioth, 2005).

2

Yehudit Inbar, Spots of Light: To Be a Woman in the Holocaust (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2007).

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. What was expected of women prior to the Holocaust?

2. How were some women able to help others in the ghettos?

3. What types of dilemmas did women face regarding their children?

4. Why would some women care for other peoples’ children?

Women and the Holocaust: Courage and Compassion

20

Rózà Robota saved lives

by heroically smuggling

gunpowder which was

used to destroy Crema-

torium IV in Auschwitz

Birkenau.

© Yad Vashem

Women and the Holocaust: Courage and Compassion

21

CHAPTER V : COURAGE

Jewish and Roman and Sinti women showed great courage during the Holocaust. Forced from their homes with just a few possessions, crowded into the ghettos under constant threat of arrest and deportation, and inflicted with every possible form of humiliation and abuse, these women had to summon the courage to face their Nazi persecutors and somehow survive.

Among these women were those who took great risks to help others, smuggle food, serve as couriers, and defy Nazi laws, policies, or ideology. Such activities alway