LECTURAS FÁCILES

CON EJERCICIOS

BY

LAWRENCE A. WILKINS

DIRECTOR OF MODERN LANGUAGES IN THE NEW

YORK CITY

HIGH SCHOOLS

CORRESPONDING MEMBER OF THE HISPANIC

SOCIETY OF AMERICA

AND

MAX A. LURIA

HEAD OF THE DEPARTMENT OF SPANISH, DEWITT

CLINTON

HIGH SCHOOL, NEW YORKCITY

LECTURER IN SPANISH, EXTENSION TEACHING,

HUNTER COLLEGE

NEW YORKCITY

SILVER, BURDETT AND COMPANY

BOSTON NEW YORK CHICAGO

COPYRIGHT, 1916,

BY SILVER, BURDETT AND COMPANY.

LA GIRALDA DE SEVILLA

ÍNDICE

Preface

Lista De Los Grabados

Mapas

Sección De Cuentos Europeos

Frases de uso común en la clase

3

El Viejo Y El Asno

8

La Piedra En El Camino

11

La Mona

14

El Juez Y El Escarabajo

14

Un Cuento De Un Perro

17

El Príncipe Y La Araña

19

La Perla Y El Diamante

22

El Muchacho Y El Lobo

22

El León Y El Conejo

24

El Camello Perdido

25

El Árabe Hambriento

28

El Oso

29

Abuelo Y Nieto

32

La Chimenea

35

Un Juez Moro

36

Pensamientos

42

El Persa Verídico

42

El Flautista De Hamelin

46

La Riña

49

El Muchacho Héroe

50

No Son Toros Todo Lo Que Se Dibuja

53

El Leñador Honrado

56

De "La Vida Es Sueño"

60

El Último Juguete

60

Versos

65

El Buen Rey

66

Arabesco

69

Niños Precoces

69

La Lección

73

Sección Panamericana

América

77

Colón

78

El Combate De Diego Pérez

83

El "Mayflower"

86

Emilio Castelar

90

El Cura Y El Sacristán

92

El Español De Varias Partes

95

El Canal De Panamá

100

Puerto Rico

104

La República Argentina

109

El Espantajo

116

El Brasil

121

El Café

127

Chile

130

El Arrepentimiento De Un Penitente

135

Una Visita A Costa Rica

140

Cuenca, La Ciudad Meridional Del Ecuador

144

El Juez Ladrón Y El Ladrón Juez

147

Méjico

153

El Perú

158

El Alacrán De Fray Gómez

163

Venezuela

166

Refranes

170

Apéndice De Verbos

172

Vocabulario

207

PREFACE

THIS book is the result of the conviction of the authors, after severalyears of experience teaching the Spanish language, that it isdiscouraging to the students of that language, as well as acontravention of all common-sense pedagogy, to place before them asreading material in the first year or year and a half, selections fromclassic Spanish novelists and short story writers.

Such writings canonly be understood and appreciated after considerable training in thefundamentals of Spanish, a language abounding in intricate idiomaticexpressions and having great wealth of vocabulary. Such writings do notprovide the student with a working vocabulary of the more common andpractical terms. To read, for instance, Alarcón's Capitán Veneno oreven Valera's El Pájaro Verde in the second or third semester of thestudy of Spanish in high schools, seems a sheer tour de force,resulting in neither a practical vocabulary nor a proper appreciation ofthese little masterpieces. Yet the strongest claim, at least at present,that can be made for a place for Spanish in the educational scheme ofthe United States is that it is a "practical"

language for NorthAmericans to know (being, as a mother-tongue in the New World, second inimportance only to English), while at the same time affording as goodlinguistic training as does a study of either French or German. But thetask of the Spanish teacher has for many years been complicated in thiscountry because no material other than that of a purely literary naturehas been available for the reading work in elementary classes.

The present volume, it is believed, provides in every-day, idiomaticSpanish, stories and articles that are simple and yet not childish, thatcan be readily appreciated by the beginner and yet withal are "muyespañol." It is suggested that it be used in the second and thirdsemesters of the high school or in the first and second semesters ofcollege, a proper place for it being determined by the age of thestudents and their previous linguistic training.

The first part, Sección de Cuentos Europeos, is based chiefly upon the Libro Segundo de Lectura and the Libro Tercero de Lectura of theseries published by Silver, Burdett & Company for use in the schools ofSpanish-speaking countries. Our thanks are given to this company forpermission to use this material and for aid in preparing this part ofthe manuscript.

The second part, Sección Panamericana, provides in Spanish interestinginformation about Latin-American countries and will serve, it is hoped,to increase, in some slight measure at least, the awakening realizationamong North Americans, especially

among young people, of the importantplace held by our sister republics of America in the resources andcommerce of the world. Those articles upon Argentina, Brazil, Cuenca,Costa Rica, and Peru are adapted from various articles appearing in thepublications of the Pan American Union, to the officers of whichsociety, especially to Mr. Francisco J. Yánes, the Assistant Director,our thanks are extended for permission to use this material in this way;also for permission to reproduce in this part several of theirphotographs of South American scenes.

Upon the selections in both parts of the book are based exercises ofvarious types. The authors believe that especial value is attached tothat form of exercise which requires working over in various ways theidioms found in the text. These idioms, selected by means of footnotes,not only aid the student in reading the text, but are of still greaterimportance in furnishing a basis for the exercises on Spanish locutionsgiven in connection with nearly every story or article. It will be foundthat the same idiom has in some cases been selected several times in thebook, but this has been done purposely for one or both of two reasons:the idiom is important and frequent in the language, or other stories ofthe book containing the idiom may not have been read before by theclass. Other exercises are: cuestionarios to be answered orally or inwriting; verb drills consisting chiefly of writing synopses of verbs;plans for the dramatization of stories; directions for giving summaries,oral and written, of stories read; word-studies (English and Spanishcognates, grouping of Spanish words of the same root, etc.); observationand description of the pictures of the text; memory passages; thecompletion of incomplete sentences based on a story read; all of which,especially in high school classes, the instructor will find desirable tohave the students work out fully.

It will be found that each English-Spanish exercise can be done byreference to the idioms and vocabulary of the article upon which it isbased. For that reason no English-Spanish vocabulary has been provided.

The important proper nouns that occur in the text are amply explained inthe Spanish-English vocabulary.

It is believed that the very full conjugations of the type-verbs of theregular conjugations given in the Apéndice de Verbos may prove to be agreat help as also may the outlines of all the common irregular verbsand the type classes of the radicalchanging and orthographical-changingverbs included in this appendix. Reference may be made to theseparadigms, if necessary, when the pupil writes out the synopses andother verb drills asked for in the exercises.

The reading matter in the first section of the book is arranged inincreasing order of difficulty, but after the first few stories havebeen covered the selections may be read in any order. Many will be foundsuitable for sight reading, especially the informational articles onSpanish-American countries.

Finally, it is hoped that in the use of this reader and its exercises,together with its section of classroom expressions and grammaticalnomenclature in Spanish, the "read and translate"

method may berelegated to at least second—may we hope to third?—place in the listof the many possible ways of covering a reading lesson in Spanish.

To our colleague Mr. Modesto Solé y Andreu, we are especially indebtedfor reading the book in manuscript and for helpful suggestions givenfrom time to time in the preparation thereof. Needless to say, he is inno sense responsible for its shortcomings.

L. A. W.

M. A. L.

SEPTEMBER, 1916.

LISTA DE LOS GRABADOS

La Giralda de Sevilla

Un Vendedor de Botijos

El Palacio Real de la Granja

Una Calle de una Aldea Española

Un Olivar de España

Una Ventana de la Alhambra

El Patio de los Arrayanes de la Alhambra

La Plaza Mayor, Burgos

Un Rincón de Sevilla

La Salida de las Cuadrillas

Pasto para las Bestias

Una Calle Sevillana

Cristóbal Colón

La Santa María

Una Brújula

El "Mayflower" en el Puerto de Plymouth

El Estadista Castelar

Un Rebaño de Ovejas en un Rancho Chileno

Las Esclusas de Pedro Miguel Miradas desde el Norte, Agosto de 1910

Las Esclusas de Gatún

El Corte de Culebra del Canal de Panamá

Vendedores de Sombreros, Puerto Rico

Las Palmas de Puerto Rico

Regatas de Buques en el Puerto de San Juan

El Acarreo do la Lana, Argentina

La Plaza de Congreso, Buenos Aires

Ganado de una Estancia Argentina

Mulas de Carga, los Andes

Panorama de la Bahía y Ciudad de Río de Janeiro

Secando el Café en el Brasil

Un Cafetal Brasileño

Vaqueros Chilenos

Un Yacimiento de Nitrato

Minando el Salitre

Llamas de los Andes

El Puerto de Valparaíso

Recogiendo las Bananas de Costa Rica

El Seminario de Cuenca

La Catedral de la Ciudad de Méjico

En la Región Minera del Perú

Una Tumba de los Incas

El Monte Misti y el Observatorio de Harvard

Un Aguador Inca

Un Cañón de los Andes en la Línea Ferroviaria de Oroya

Estatua de Bolívar, Plaza de Caracas, Caracas, Venezuela

En el Mercado de Caracas

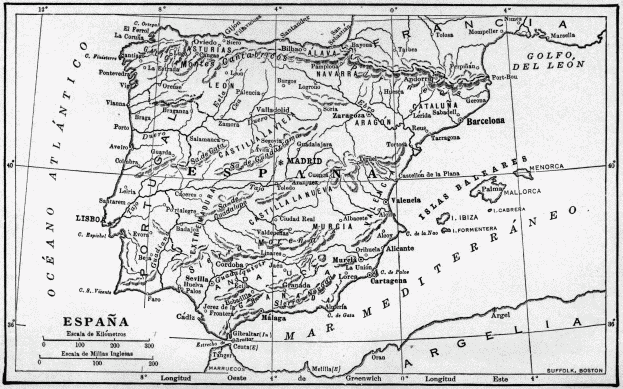

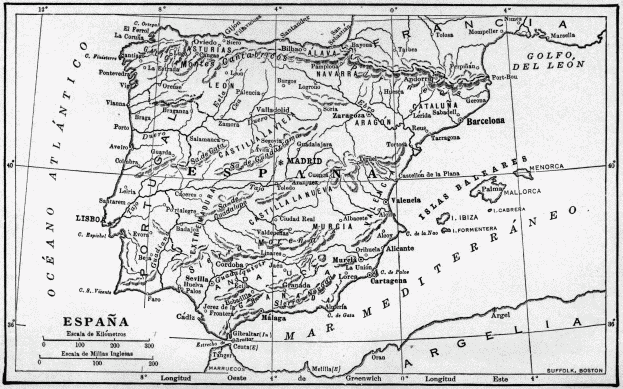

MAPAS

España

América del Sur

América Central

[Page 2]

MAPA DE ESPAÑA

[VIEW ENLARGED]

SECCIÓN DE CUENTOS EUROPEOS

Page

[3]

LECTURAS FÁCILES

[Transcriber's note: The spelling and accentuation of the Spanish in the original, hard book have been retained.A small number of words which appear here with accent are no longeraccented in modern-day Spanish: vi (ví) vio (vió) fui (fuí) fue (fué)and dio (dió) construido (construído) heroica (heróica).]

FRASES DE USO COMÚN EN LA CLASE

Saludos y despedidas

Buenos días, profesor, profesora. Good morning, teacher.

Buenas tardes. Good afternoon.

Buenas noches. Good evening, good night.

¿Cómo está usted?

¿Cómo lo pasa usted?

How are you?

¿Cómo se encuentra usted?

¿Qué tal?

¡Hasta luego!

See you later!

¡Hasta más tarde!

¡Hasta la vista! Till we meet again!

¡Adiós! Good-bye!

Asistencia y puntualidad

Voy a pasar lista a la clase. I am going to call the roll.

Juan Brown. Presente. John Brown. Here.

¿Quién está ausente? Who is absent?

¿Quién sabe la causa de la ausencia de la señorita Smith?

Who knows whyMiss Smith is absent?

¿Por qué llega usted tarde? Why are you late?

¿Cómo se llama usted? What is your name?

Me llamo Pedro Smith, para servirle a usted. My name is Page

[4]Peter Smith,at your service.

Fórmulas de cortesía

Fórmulas de cortesía

Haga usted el favor de

(más el infinitivo).

Please (plus the infinitive).

Tenga usted la bondad de

(más el infinitivo).

Gracias. Muchas gracias. Mil gracias. Thank you.

De nada. No hay de que. Don't mention it.

Dispénseme usted. Con permiso suyo. Excuse me.

La lección de lectura

Póngase usted de pie. Rise.

¿Cuál es la lección para hoy? What is the lesson for to-day?

Abra usted el libro. Open your book.

Lea usted. You may read.

¿Lo entiende usted? Do you understand it?

Traduzca usted al inglés. Translate into English.

Dígame usted en español lo que acaba de leer. Tell me in Spanish whatyou have just read.

Siga usted leyendo. Continue reading.

Repita usted cuando le corrijo. Repeat when I correct you.

Usted pronuncia muy bien. You pronounce very well.

No lea usted tan de prisa. Do not read so fast.

En el pizarrónVaya usted al pizarrón. Go to the blackboard.

Tome us