be made complete by “so prudent a use of this

of a democratic republic, one might mention an incident

blessing.”

from his earlier years. He had ended his military career

as the revolutionary commander with a poignant fare-

Finally, desiring “the permanency” of “your happiness

well to the officers who had served faithfully under him.

as a people,” he offered disinterested advice similar to

Woodrow Wilson noted that, in the final years of the

that he urged when he disbanded the army.

Revolutionary War and “the absence of any real govern-

On that occasion, Washington, drafting his 1783 “Circu-

ment, Washington proved almost the only prop of author-

lar Address,” was responding to the urgings of several of

ity and law.” How this arose from Washington’s character

his colleagues to leave his countrymen a political testa-

was displayed fully in Fraunces Tavern, November 23,

ment to guide their future considerations. Washington

1783. The British had departed New York, and the

acknowledged these urgings

general bade farewell to

in a letter to Robert Morris

his men. At that emotional

on June 3, 1783, by stating

moment, at a loss for words,

that he would “with greatest

according to contemporary

freedom give my sentiments

accounts, Washington raised

to the States on several polit-

his glass: “With heart full

ical subjects.” He followed

of love and gratitude, I now

the same model in 1796,

take my leave of you.” He

upon leaving the presidency,

extended his hand, to shake

without need of urging.

the hands of his officers

Washington’s retirement

filing past. Henry Knox

from the presidency in 1796

stood nearest and, when

after two four-year terms

the moment came to shake

in office was important

hands and pass, Washington

because it cemented the

impulsively embraced and

concept of a limited presi-

kissed that faithful general.

dency. Washington could

Then, in perfect silence,

Washington’s retirement was made gratifying by his love for his plantation, have used his military stature

he so embraced each of his

Mount Vernon.

and his enormous popular-

officers as they filed by, and

ity to become an autocrat; yet, he refused to do so. His

then they parted. This dramatic end to eight years of

modesty certainly appealed to the public. The spon-

bloody travail demonstrates Washington’s instinctive

taneous and universal acclaim that welcomed him home

wish to build concord out of conflict, and his ability to

from the Revolutionary War in 1783 was duplicated on

recognize the merit and value of others, as well as his

this occasion.

own.

This time, however, he had completed a much more

When Washington declared, upon retiring from the

trying task, the increasingly bitter party strife having

presidency decades later, that “`Tis substantially true,

made even him an open target. Not only had the coun-

that virtue or morality is a necessary spring of popular

try been solidified and its finances put in order, but also

government,” he stated in words what his earlier actions

ominous threats of foreign war that loomed over his last

symbolized: that the success of the democratic enterprise

five years in office had greatly declined even while the

depends on a certain willingness to give others their due

country had been strengthened. Washington also took

and to relinquish some claims of the ego and of power.

satisfaction that resignation removed him from that

The very first condition for the preservation of a demo-

unfamiliar position of being held up to public scorn and

cratic republic, Washington believed, is the foundation

ridicule by “infamous scribblers,” a source of grief and

within the individual of prudent reason. Speaking of

irritation to every president since Washington as well.

the people as a whole, Washington ultimately called this

quality “enlightened opinion” and “national morality.”

20

By commending morality and reason to the American

amendment) represents continuing affirmation of the

people as he left office, Washington hoped that the

people’s authority.

power of his example had made them capable of follow-

ing duty over inclination. By limiting his own behav-

W. B. Allen is a professor of political science at Michigan State University, ior and prerogatives in office and by enduring conflict

specializing in political philosophy, American government, and jurisprudence.

Currently on sabbatical leave, he is a visiting fellow in the James Madison without resorting to tyranny, Washington made it clear

Program, Department of Politics, Princeton University,

that he wished his legacy to be a true democracy, and not

translating Montesquieu’s Spirit of the Laws . His publications include a reversion to traditional autocracy. His refusal to seek

George Washington: A Collection , and Habits of Mind:

a third presidential term cemented that. Washington’s

Fostering Access and Excellence in Higher Education

“falling” in 1796 was his people’s rising. Continuing

(with Carol M. Allen).

respect for the two-term presidential precedent in the

United States (now enforced by constitutional

Tourists can visit Mount Vernon today, to get a

glimpse of Washington’s America.

21

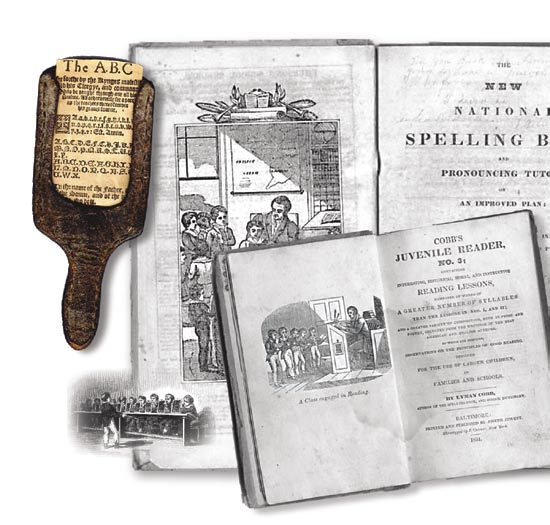

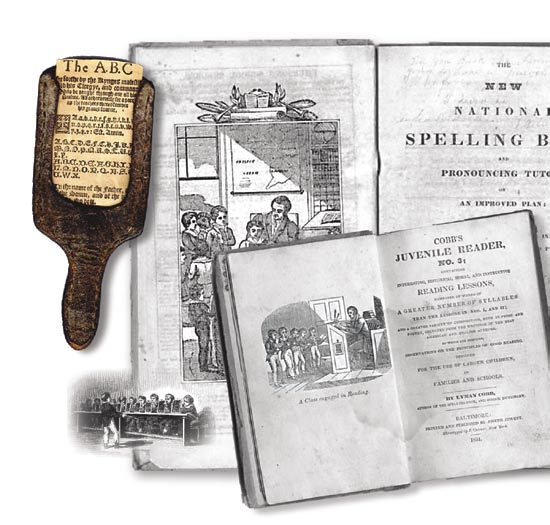

The technology of education has changed, at least to some extent,

since the time of the 16th-century hornbook shown at left, or of 19th-century schoolbooks (below). Over the course of history, however, what information children should be taught, what methods should be used, and who may have access to education, have been perennial social issues.

22

by Carl F. Kaestle

Victory of the Common School Movement:

A Turning Point in

American Educational History

AMERICANS TODAY COUNT ON THEIR PUBLIC SCHOOLS

TO BE FREE OF EXPENSE, OPEN TO ALL, AND DEVOID OF

RELIGIOUS SECTARIANISM. ALTHOUGH FAMILIES ARE

PERMITTED TO ENROLL THEIR CHILDREN IN PRIVATE

SCHOOLS AT THEIR OWN EXPENSE IN THE UNITED STATES,

THE PERCENTAGE OF PRIVATE SCHOOL STUDENTS HAS

BEEN STABLE AT ABOUT 10 - 12 PERCENT FOR HALF A

CENTURY. THE GREAT MAJORITY OF STUDENTS ATTEND

PUBLIC SCHOOLS, FROM THE FIRST TO THE TWELFTH YEAR

OF SCHOOLING, THE FULFILLMENT OF A CRUCIAL POLICY

DECISION MADE IN EACH INDIVIDUAL STATE IN THE NORTH-

ERN PART OF THE COUNTRY IN THE 1840S, AND IN THE

SOUTHERN STATES IN THE LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY.

IT WAS CALLED “THE COMMON SCHOOL MOVEMENT.”

Horace Mann, pictured here, an educational reformer of the 1840s.

23

Free schools open to all children did not exist in colo- taught children their ABC’s through rhymed couplets, nial America. Yet, something like modern American

beginning with “In Adam’s Fall, We sinned all,” and

public schools developed in the 1840s, when a majority

concluding with “Zaccheus he Did climb the Tree, Our

of voters in the northern regions of the United States

Lord to see.”

decided that it would be wise to create state-mandated

Schools offered brief terms, perhaps six weeks in win-

and locally controlled free schools. Once this model of

ter and another six weeks in summer, attended mainly

schooling prevailed, the stage was set for the creation of

by young children who were not working in the fields.

an inclusive free-school system in the United States.

These practices swayed to the rhythms of agricultural

In the British colonies of the 17th and 18th centuries,

work and the determination of most towns to provide

schooling was not compulsory, not free of charge, not

only modest resources for schools. Formal schooling was

secular, not open to all, and not even central to most

more extensive for a tiny elite, as it was in America’s par-

children’s education. Decisions about the provision

ent country, England. In the colonies, only a few boys of

of schools were made town-by-town. Girls were often

European ancestry might go on to more advanced schools

excluded, or allowed to attend only the lower-level

for English grammar and then, for an even smaller

schools, and sometimes at different hours from the boys.

number, tutoring in Latin, leading to Harvard College, or

In most towns, parents had to pay part of the tuition to

Yale, or William and Mary. The majority of these privi-

get their young educated. These barriers to the educa-

leged few then became ministers, rather than leaders in

tion of all characterized the New England colonies in

secular society.

the Northeast as well as those in the middle-Atlantic and

The rest of the children learned most of their literacy,

the South. In those sections of North America that were

adult roles, work skills, and traditions outside of school,

then governed by Spain or France, even less was done

from a constellation of institutions, principally the home,

for education. Christian missionaries made intermit-

the workplace, and the church. However, as colonial

tent efforts to evangelize Native Americans and African

society became more highly populated, more complex,

Americans through religious education across North

and more riven by faction in the 18th century, competi-

America; but schooling, whether local or continental, was

tion among rival Protestant denominations and quarrels

not primarily a governmental matter.

developed over religious doctrine. In addition, political

and financial issues ultimately brought relations between

The Religious Roots of Colonial the colonists and the English homeland to a breaking point. Thus, the uses of literacy for argumentation

Schooling

– both in oral and written form – grew. And as agricul-

ture became more commercial and efficient, it brought

more cash transactions, more focus on single crops, and

However, in spite of patchwork, casual customs of

the prospect of more distant markets, into the country-

schooling throughout the British colonies, there was a

side, reinforcing the value of literacy. In the growing

push for literacy among many colonists, based largely

coastal towns of Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and

on the Protestant belief that lay people should learn

Charleston, and in some inland centers like Albany and

to read the Bible in the vernacular tongue (that is, for

Hartford, philanthropic groups and churches, responding

British colonists, in English, rather than Latin or Greek).

to the increase in poverty and its visibility, established

Passing a law in 1647 for the provision of schools, the

free schools for the moral education of poor children, on

Massachusetts colonial legislature commented that “old

the model of English “charity” schools.

deluder Satan” had kept the Bible from the people in

the times before the Protestant Reformation, but now

they should learn to read. Thus, the legislature decreed,

towns of over 50 families should provide a school. They

did not specify that the education had to be free, nor did

they require attendance. The law was weakly enforced.

In effect, parents decided whether to send their children;

if they did, they had to pay part or all of the cost; and

religion was without doubt or question intertwined with

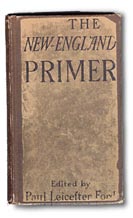

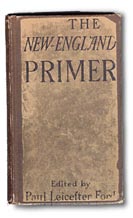

education in those days. The most popular schoolbook

in British colonial America, The New England Primer,

24

The Common School Movement ing in these institutions. Even for white children, the terms were brief, the teachers often poorly educated,

and the buildings generally in poor condition. The rural

Given these 18th-century dynamics, one might have school became a favorite target of school reformers later expected that when the colonists’ victory over

in the early 19th century. Michigan’s superintendent,

British forces in the American Revolution finally left

John Pierce, called little rural districts “the paradise of

newly-minted Americans free to establish republican

ignorant teachers”; another report spoke of a district

institutions to their liking, schools would have been high

school building in such bad repair that “even the mice

on the list. Indeed, many of the Revolution’s leaders

had deserted it.”

thought they should be – including Thomas Jefferson

and Benjamin Rush. Jefferson wrote from France in

1786, advising a friend to “preach a crusade against

The Monitorial School Model

ignorance,” and support free schools in Virginia. Rush, a

Philadelphia physician and signer of the Declaration of

In cities, there were more opportunities. Even in the

Independence, proposed a similar bill for free schools in

18th century in urban areas, there were several differ-

Pennsylvania.

ent kinds of schools, funded in different

Leaders of this movement for state

ways and with different levels of financial

systems of common schools in the early

resources. A modest amount of “charity”

national period came from both the Jef-

schooling provided some free instruction

fersonian Republicans and the Federal-

for children of poor whites and of African

ists. But their efforts failed in their state

Americans, often subsidized by churches

legislatures. Most free citizens, it appears,

and by state and local government. Such

thought that the patchwork colonial mode

efforts resulted in African Free Schools,

of education was still quite sufficient. In

“infant” schools for the two- and three-

particular, Americans were wary of any

year-old children of the indigent, and

increase in taxes (which had been a major

other types of sponsorship. As time

point of contention with England) and did

passed and as concern grew, many cities

not want their fledgling state governments

in the new Republic experimented with

to meddle in affairs that had always been

a type of charity school, the “monitorial”

local matters for towns or families to de-

school, which became popular in Eng-

cide. After Jefferson’s bill for free schools

land, Europe, and Latin America in the

in the Virginia legislature had failed twice,

1810s and ‘20s. Invented by Joseph Lan-

he complained to his friend Joel Barlow in

caster, a Quaker schoolmaster in England,

1807, “There is a snail-paced gait for the

the “monitorial” school model encour-

advance of new ideas on the general mind, This schoolbook was published in 1727 in aged more advanced pupils to teach those under which we must acquiesce.” Boston and later reprinted. “Primer” who were less advanced. Lancaster wrote originally meant book of prayers; it came

Thus, in the countryside, towns still

to mean an introductory school text. The many manuals in his efforts to popularize decided whether to have a school, and

boundary between religious and secular edu- the methods. Lancaster attempted to de-if so, how to fund it. The cost was usu-

cation is still being defined in many societies. fine appropriate discipline and to provide ally covered through some combination of taxes on all

detailed instructions for classroom procedures. At a time

citizens plus tuition fees for the parents of children who

when boys were routinely paddled for school infractions,

attended. Sometimes parents paid by providing food

advocates applauded Lancaster’s ideas about motivation

for the teacher or firewood for the school, but usually

without corporal punishment, discipline motivated by an

it was cash. Parental payments were called “rate bills.”

active curriculum and competition, neutrality with regard

Sometimes the school would be free for all children for

to religious denominations, and, perhaps most important,

a set amount of time and then a “continuation” school

economy of expense. Lancaster claimed that with his

would be provided for those whose parents were able

system a single master could teach 500 poor children at

to pay. Thus the amount of schooling a child received

a time. By the 1820s, Lancasterian schools had popped

was in the last analysis determined by wealth. At most,

up in Pittsburgh, Harrisburg, and many other Pennsyl-

there would be a single school for each town or district.

vania towns; in Detroit, Michigan; Washington, D.C.;

Blacks and Indians in general received no formal school-

Hartford and New Haven, Connecticut; Norfolk and

25

Richmond, Virginia; and dozens of other cities. In New

munity. Traditional opponents of taxation labelled this

York City and in Philadelphia, reformers organized entire

an unwarranted and oppressive intrusion of state govern-

networks of Lancasterian monitorial schools, systems that

ment into local affairs; however, Henry Barnard, Con-

became the physical and organizational basis of the later

necticut’s school superintendent, called it “the cardinal

public free schools of those cities. Later critics derided

idea of the free school system.” Reformers also urged

the monitorial schools for regimenting their poor students

the centralization of the little rural districts into larger

and separating them from other children, but Lancaster’s

town-wide units, for better supervision and support.

ideas helped popularize the notion of a school “system,”

Simultaneously, in urban settings, school reformers of the

referring not only to the pedagogy and curriculum but to

same period began to focus their efforts on absorbing the

the organization of schools into a network.

charity schools into free public school systems and then

For parents with a bit more money, there were inex-

trying to attract the children of more affluent parents into

pensive pay schools advertised in the newspapers, taking

these “common” schools. The idea of the school as a

in children whose parents could afford a few shillings

common, equal meeting ground took on great force for

a quarter. The wealthy educated their children with

reformers, and they aimed their criticisms at the evils of

private tutors or sent them to expensive boarding schools

private schools. A system of private schools for the rich,

in the English style, now

said Orville Taylor in 1837,

increasingly available to the

“is not republican. This

English-speaking ex-colo-

is not allowing all, as far as

nials. The cream of soci-

possible, a fair start.” The

ety might even send their

present system, Henry

favored sons and daughters

Barnard complained, “clas-

to acquire intellectual and

sifies society . . . assorting

social finesse in academies

children according to

abroad. Well into the 1820s

the wealth, education, or

and ‘30s, “free” education

outward circumstances of

thus connoted only limited

their parents.” As Jeffer-

privileges granted to the

son had discovered earlier,

poor, and was distinctly

however, old practices

dependent on the goodwill

die hard. Even Horace

of local congregations, both

Mann, the best known of

Protestant and Catholic,

the education reformers in

or perhaps the largesse of

the 1840s, lamented the

Modern tastes might find this old primer rather gloomy and limiting. Most would nondenominational philan-argue that pedagogy has improved over the centuries.

slow progress of his efforts,

thropic societies. In New

labeling his opponents as

York and elsewhere these charity schools might receive

“an extensive conspiracy” of “political madmen.”

some support, variously from the city council or the state.

There remained much support for small-scale district

Our current distinction between “private” and “public”

control. In Massachusetts, for example, traditional Prot-

education had not yet crystallized.

estants of the Congregational denomination rightly per-

ceived that the state would use its influence to discour-

The Common School Reform

age the advocacy of particular doctrines in such common

schools. In New York state, a petition from a little town

Movement Gathers Steam

in Onondaga County complained that the newly passed

school law of 1849 allowed people “to put their hands

into their neighbors’ pockets” to get support for schools.

Meanwhile, in the small towns and countryside,

Roman Catholics in New York City fought the creation