APPENDIX A

WHY I BUSTED COLLEGE (Reprinted with permission from Seventeen)

I am a bustee from an Ivy League college. I’m not alone. One

out of every six students who enter a major eastern college or university

leaves without a diploma. Here is my story, representative of many, told with

some degree of shame and with the hope that it might keep someone else from

doing the same thing.

I’m not dumb. I have an IQ upward of 140. I graduated in the

upper half of my class at a top eastern preparatory school, and I applied to

only one university—Cornell in Ithaca, New York. Like many of my classmates, I

wasn’t sure what career I wanted and felt that college was probably the best

way to find out. There was also a definite angle of glamour and intrigue that

went with the thought of college. Then, too, I considered college the next step

toward maturity—a step that parents and others expected of me. Put simply, I

had been working, eating and breathing college, until college—in my case

Cornell—had become a goal in itself. I came through satisfactorily on my

entrance examination and in the fall of 1956 was proud to become one of the

1,611 men freshmen “on the hill.”

Since I was not sure what I wanted to do, I entered the

liberal arts college with some thought of law. I felt I would enjoy working

with people, researching and compiling cases, preparing them with common sense,

presenting them with logic and winning them over with the zeal of a crusader.

I’m the kind of guy who likes to argue.

Also, I reasoned, law would give me an excellent background

for business.

Since Ithaca was my hometown, Cornell was familiar to me. I

faced no problem of adjusting myself to a new environment. I moved into the

men’s dorm to continue life on my own—away from home—and to meet more people.

Classes began September 19, two days after formal

registration. I bought my books and thumbed through them, but put off reading

the first assignments. Everyone was trying to meet everyone else. Orientation

rallies, dances and coed parties followed one another in rapid succession. I

wasn’t worried about grades. I was confident that my prep school background would

carry me through.

Within two weeks, I became fast friends with seven other

freshmen, most of whom had also attended prep schools. When a person enters a

large college, he can’t help feeling lost. But it is a sort of contest as to

who can appear the most casual and unconcerned. I doubt that I came close to

winning, but I know this—I tried hard. And among my friends I had some tough

competition. Ours was a varied and close-knit crew.

John was from Ithaca, and we had been close friends long

before college. Rip had attended prep school with me. We had both wrestled on

the school team, and we managed to get into the same dorm at Cornell. His

roommate, Sabu, was a foreign student from Iran who welcomed the American

routine.

Just down the hall from me, on the same corridor, was Binge.

He and his roommate, Brew, had both gone to a military academy. Later, we fell

in with Skoal, a graduate of a different prep school, and a high school

graduate named Jud. Each of us was different; that’s what made the group

dynamic.

Wherever we went, we went together, and many were the nights

we’d go out looking for excitement. Since I had access to a car, there were

always the safaris to nearby colleges. All this time my books collected dust.

I went into my first quizzes cold and unprepared. And I

busted them flat.

Well, it bothered me, but I really wasn’t worried, and I

wasn’t alone. We all felt that we could do better on the next test, get a high

mark and bring our averages back up.

But the difference between the prep school I had attended

and Cornell was becoming more apparent. It pervaded the atmosphere—both

academic and social.

At prep school, twelve students would sit about a huge

elliptical table with the master at one end. The masters were instructors,

advisors, debate leaders and friends, all in one. Classes would often start

with a joke and continue in a chatty style. Students entered into discussions,

and if you didn’t understand a particular point, all you had to do was to raise

your hand to get an explanation.

At Cornell, for the most part, the classes were larger—some

of the lecture classes had more than two hundred students. Often I found myself

sitting mutely in huge lecture rooms, rapidly, almost frantically, jotting page

after page of notes, which usually were merely so many meaningless and

unrelated words.

There was no respected companion drawing out each student

and inspiring him to participate. The exalted professor was telling. And when a

professor would rapidly join the rest on the page, only later, after reviewing,

was I able to discover extraneous material and weed it from the important.

At prep school also I had a strong goal. The goal was to get

accepted into college. Toward this goal, it seemed, every master, advisor and

headmaster was intent on helping us travel.

Once prep school was behind, I lost this goal. I was in

college and figured I would have no trouble staying there.

Beyond high school had lain college, with its promises,

intrigues and freedoms. Beyond college lay life—which is a lot tougher than

college, and most of us inwardly realize this. We each had four or five years

before leaving our warm, secure, little world, and we wanted to enjoy every

moment of it.

With the sudden release from personal guidance, interest and

pressure came a slack in my studious intentions. At Cornell, my time was my

own, and an endless variety of functions were beckoning. It was easy to become

a glutton.

But the assignments kept pouring in—a report here, a short

quiz there, a paper today, and an hour exam tomorrow. I failed to stay on top

of them, let alone catch up on my back work. Why? I’ve asked myself that

question a hundred times.

Most of the time I spent “studying” was really an exercise

in self-deception. I would sit in front of a book for hours on end. When I had

finished, I would find that I had merely substituted the putting of words on

paper for learning. The brainwork still lay before me.

I was taking courses in English, French, psychology, English

history, basic military science (ROTC), and physical education. The minimum

number of required course hours in most colleges today is fifteen per term.

With six for French, I was carrying eighteen.

My English course was primarily theme writing. I had always

enjoyed that, and I liked my professor. He spoke our language. I enjoyed

English immensely.

Not so with French. It was a grind. I had terrific

instructors, but I had already taken three years of French and was tired of it.

A language was required at Cornell, so I had to take it.

Psychology, I found extremely interesting, although the

professor sometimes lost me in the shuffle of terms and philosophies.

I liked my professor for English history, but not the

course.

History came hard for me, and that was my first inkling that

I could never be a lawyer. The inkling grew later.

Military science was a valuable experience. It was required,

as was physical education.

I found this combination of courses a good brainful, but we

were all in it together. And my friends and I were having our fill of college

fun, too.

One night about eight, the six of them (Jud was already in

bed) came into my room and asked me to go stir up a little excitement with

them. Since I had put off a five-thousand-word theme until the last minute, I

said no. That was one of the few times I can remember saying it. They went on,

anyway. At two that morning I had finished and was deep in sleep.

An hour later, they were banging at my door.

When I saw Binge grinning there, a bale of way hay strapped

to his back, a huge Bridge out sign under one arm, I couldn’t help laughing.

Then Rip came thumping down the hall behind a no pArking sign. A squeaking

noise signaled the arrival of Brew, pushing a wheelbarrow full of wet cement.

The rest of the fellows each held a red blinker-lantern.

While the rest of the dorm slept, we scattered hay in every

crack and corner of the building. We rolled the wheelbarrow into another dorm,

hid the signs in a nearby graveyard.

This was the most extravagant of many escapades, none of

which was allowed to end when it was over. We kept each adventure going for

nights on end, rehashing it in bull sessions. Hardly a day passed when at least

one of us didn’t feel he had something important to relate, and we would gather

in a room and talk late into the night.

All these ill-conceived doings bit huge chunks out of my

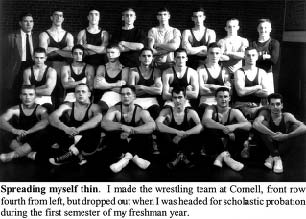

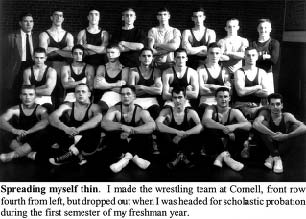

study time. Extracurricular activities stole even more. All through the year,

we freshman were warned by counselors and advisors against “spreading yourself

thin.” But I had dreamed of wrestling for Cornell when I was in prep school,

and I had to make the team. I was also the art editor of Sounds of Sixty, our

class newspaper.

At the end of the term, the little blue probation slip ended

my extracurricular career.

I had passed all my courses; 60 is passing and I had an

average of 69.4. But in Cornell liberal arts school you must have three courses

over 70 to stay off pro. I had only two—English (80) and History (75). If I

wanted to stay in Cornell, I had to get off pro.

And make no mistake, I wanted very much to stay in Cornell.

Fraternity rushing went on for the first two weeks of the

sec

ond term. I should not have rushed on pro, but I did. So did

my friends. And we all made good fraternities.

There was the usual orientation to fraternity life, pledge

raids, meetings, and parties. And then things calmed down a bit. My fraternity

brothers were concerned over my grades and tried to help. I began in earnest to

raise my marks.

The courses were a little more to my liking this term.

English, French, psychology, English history, ROTC, physical education again,

and biology, a subject in which I had done well at prep school. We even used

the same text.

A Cornell tradition is “freedom with responsibility,” and

class attendance is, within limits, up to the individual students. In biology,

each cut over three took a point off the final grade. I knew this but figured

incorrectly that if I did well, the rule wouldn’t apply. Overconfident, I cut

some lectures.

Then I had two bad breaks.

I knocked my right thumb out of joint falling off a

motorbike when I tried to carry a girl sidesaddle. I had to wear my arm in a

cast and couldn’t write for a full month. Lectures were completely forsaken,

but without getting special permission from the lecturers. Later, I contracted

a virus that put me in the infirmary for a week.

My English dropped to a 75, partly due to the extra time I

spent pulling my grade in psychology. I got a 70 in French. The other two

courses I busted from cuts. Twenty-one points for cuts were subtracted from my

final average of 80 in biology. Cuts influenced my history professor to give me

a disciplinary mark of 55.

The biology incident, in particular, set my teeth on edge. I

spoke to my biology teacher, but he turned a deaf ear. So I received my

suspension notice. One hundred thirty-two boys in my class didn’t make the

grade. It was pretty sad to see some of my closest friends walking out the back

door with suitcases in their hands. It was sadder still to be among them.

I got two jobs and began working a twelve-hour day, driving

myself to relieve my depression. I walked two miles to get to my second, and

another half-mile in the evening to get back home.

Finally, I got my courage back and, urged by one of my

professors, I sent a letter of appeal to the Reviewing Board at Cornell. I

cited my broken thumb and illness and vowed never to cut again. Then I could

only wait.

Each day I took my stand beside that mailbox expecting the

board’s decision. When it finally arrived, I remember holding the envelope for

a while, turning it over and over in my hand until I could work up courage to

open it. I tore it open. A glance. I was back in! I was to be readmitted that

fall. There was one condition: I had to take two courses at Cornell summer

school and get at least 75 in both.

When summer school began, I quit my morning job to attend

classes. I made it through with a 75 and an 80, and I was back at Cornell that

fall! This time I lived at home instead of the fraternity house. I didn’t waste

time with friends. I didn’t cut lectures. I didn’t date. I went up to my room

and closed the door and studied. I spent hours each day bent over my books. And

I think I had the neatest collection of notes, typed on bond paper and bound,

of any student since the University opened in 1868. I really worked.

And college today is work. You can’t stay in a good college

any more just because you can pay. You have much less time than years ago for

coeds and drinks at Zinck’s. The toughest thing about education today, in my

opinion, is learning how to go about getting it.

My hard work did pay off. Up to the finals, I had an 83, 78

and 77 respectively in sociology, biology and Far Eastern studies, with a lower

average of 68 in Great English Writers and of approximately 60 in British

government. These averages would easily get me off pro, and I was beginning to

feel like a human being again.

I moved into the fraternity. I was finally going to be

initiated; I had a 1952 Nash-Healey sports car of my own; a group of us were

going to start a combo in which I was to play the drums, and I knew the courses

I would be taking next term would be primarily of my choosing. Everything was

finally going right.

Then came the finals. I laid out my study plans, I sweated

and crammed. I forgot about sleep and taxed myself to the limit. And the

results began to come in.

My final mark in English, 65, was consistent with my work

for the term, and I was content with it. I had passed and I hadn’t particularly

enjoyed the “jug-jug, pu-we, to-witta-woos,” and “hey nonny nonnies” of the old

English writers anyway. I passed ROTC again. Biology was easy. I made an 88 on

the final, got an 80 as a final mark. Government, which had been giving me

trouble all term, I busted. But I was still in the running. I was sure I had

done well on the Far Eastern exam, but I was worried about the sociology final.

Much to my surprise, my sociology grade came in at 85. I had still to get my

Far Eastern studies mark.

Then it came. My final in Far Eastern had been low, so low

that the final mark was 63. That was a blow I had not expected.

I couldn’t understand what had happened. I saw my professor

and asked to see the exam. He told me it was “inaccessible,” that it and

another quiz had counted more than I expected. He was as immovable as a

concrete wall and offered about as much sympathy.

All I could do was wait for the drop notice.

The board didn’t meet for a while so I continued to go to

classes. I wrote another appeal letter, but I had no real basis for an appeal

this time. When the board met, I was dropped from Cornell. This time for good.

Well, the end had come and I left Cornell. Again, I wasn’t

alone. Of the eight in our group, only three are now in Cornell. Five of us

failed to meet the pace.

This time I lost all hope, and friends and acquaintances

didn’t help much. For each person who genuinely cared, there were two who cared

more about extracting a sadistic pleasure from it. Many who asked me about it

would, under the guise of sympathy, stick in the knife and give it a little

twist.

Of those few who genuinely cared, I remember two. One was a

wonderful girl I had known and felt close to most of my life. We went for a

long drive soon after I learned that I had busted and she proceeded to outline

my weaknesses and lay bare the reasons for my failure. She strongly suggested I

go into the army to get back on my feet. She meant well, but what she said

really challenged me to prove I could continue my education somehow.

I got the confidence to back up the challenge a few nights

later. I had a long talk with one of my fraternity brothers, who told me to

hold up my head and keep working until I could get back into a college that

would give me what I wanted. He said he knew I could do it.

That really helped. The next week, I took a series of

aptitude and interest tests to help me plan my future. All the results pointed

to writing and journalism. I signed up immediately for two journalism courses

in the Cornell Extension School.

I enjoyed them immensely, and then I was sure. I was going

into the writing field, and somehow I was going to get into another college so

that I could develop my ability. I knew the shadow of my bad record loomed over

me. One possibility presented itself: The University of North Carolina in

Chapel Hill. It has an excellent school of journalism, and since I was born in

that state, I seemed to have at least a chance.

Dad and I flew down one weekend to see what my chances were.

We talked to everyone, my records were studied and the admissions director

decided to give it a try. I was to take two more courses by correspondence and

make at least Bs in both. Then I was to go to a double session of Carolina

summer school, take four more courses and come out with a B average in all.

It was a lot of concentrated work—study, eat and sleep, with

a little black coffee on the side. But I was working to get into a college

again, and all the determination I’d had at prep school came back.

By June 9, 1958, I had finished the correspondence courses,

taken the exams and was attending my first classes at Carolina summer school.

The correspondence marks had come through a day before—an A in English, a B in

math. The Cornell marks came soon after—86 in advertising, 83 in writing.

So far so good.

The summer started off fine. I was pretty lonely, but since

I was there to do a job, it didn’t matter.

To fill in all the loneliness, I began writing on the side.

I’ll never forget my first published editorial. I had written it to a local

paper, the Chapel Hill News Leader. Over a cup of coffee on the morning of July

3, I saw my name in print for the first time.

Later, missing a girl back at Cornell, I began pouring my

feelings into poems. My first poem appeared in the Raleigh News & Observer

in August. I bought every paper in Chapel Hill, and then I drove to Raleigh to

buy more.

Life was great. When I registered for the fall term at

Chapel Hill, I lost exactly half of my Cornell credits. But fall term was fine.

I stuck pretty close to my B average and made a lot of new friends. I got to

know my instructors. I went to my advisor if any trouble developed.

Spring term went well too. I’m on my way now. I’m in a good

university—the oldest state university in the nation. I’m enjoying my studies.

I know where I’m going.

There have been some basic changes in my study habits. I

spend less time organizing, typing notes and outlining material, and more time

just plain learning. I read the assignments and keep up with the professor, day

by day. I enter into discussions as I did at prep school.

If I dislike some of the professor’s ideas or philosophy, I

listen

anyway. I’m in college to learn, not rebel, for I have begun

to realize that the truly educated man has very few prejudices.

Carolina is no easier than Cornell. But it’s easier for me.

Why? I’m working harder, I’m back in college—to stay.

To stay until I walk out the front door, a diploma in my

hands.