Chapter 1. Using untranslated materials in research

What are these documents?

These texts are digitized versions of

documents found in Rice University’s Woodson Research Center. They

are a sampling of a collection of several hundred documents that

comprise Rice’s Americas Archive. The selection of documents used throughout this module were all originally written in Spanish and have been translated into English. I refer to a couple of translated documents here, but you may wish to browse through all of the documents listed in the upper left sidebar, all of which are available on-line (or will be soon!) in three

formats: their original format, a transcription, and a

translation.

What is the difference among the

formats?

The original version is a scanned image of

the document, so it shows what the document actually looks like - a letter, a printed pamphlet, etc.. The transcription is a typed

version of the original in its original language. The

transcription should retain any misspellings, typos, and other

“errors” that are found in the original. The translation is an

English version of the document. The translations are meant to be

easy to understand and also to retain the “flavor” of the original.

Since the documents were written about 150 years ago, the

translations may also have an old feel to them.

What is the advantage of looking at the

original?

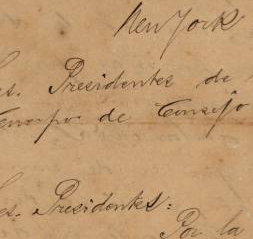

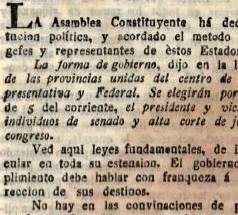

The original version can give you a feel for

the type of text you are perusing and also give you some clues

about its author. The two documents below are visually quite

different; one is a letter written by José Martí and the other is a

Central American governmental manifesto.

Even if you do not understand Spanish, the differences between

these documents is very clear. You can tell just by glancing at them that they

served quite different purposes. The visual differences

are not at all apparent in the transcribed or translated versions.

Please refer to the module "Using original

documents on the Mexican American War" for more information on the

value of looking at the original versions of these

documents.

What is the advantage of looking at the

transcription?

Transcriptions are almost always much easier to read than

originals. It might take you an hour to read José Martí’s

letter in his handwriting but only a few minutes to read its typed

transcription. You may wish to look at the transcription first to

determine if a document is of interest to you. Just

remember that a transcription is an interpretation of the original

document. If you decide to

work closely with a document, you may also wish to read it in its

original Spanish version as well as its translated version.

Why should I look at the translated

version?

If a transcription is an interpretation of the

original, a translation is an interpretation of the transcription.

A translator typically transcribes a hand-written document and then

translates it. In this sense, a translation is two steps removed from the

original.

That being said, someone who does not

understand Spanish would not be able to understand much, if any, of

the content of these documents without reading the translation. If

you understand some but not a lot of Spanish, reading the transcription might be

fairly laborious but reading the translation quite fast. This could

help you determine whether or not you want to spend more time with

the document.

What is the value of comparing all three

versions?

It can be quite useful for a student who

speaks some amount of both Spanish and English to browse through

all three versions of the document. The translation may have

interpreted some words in one sense, while you may prefer to think

of them in another sense. In addition, not all words and their

translations have exactly the same connotations

Cecelia Bonnor, who transcribed and translated the letter from J.G. de Torde along with several other documents in the Americas Archive, says that when working with originals "I have had to contend with different hands, which must be deciphered in order to allow the documents to speak for themselves. In particular, I am thinking of the Goliat letter, the first manuscript document I translated for the Americas project as it presented interesting and immediate challenges having to do with the common practice of abbreviating words. Specifically, the first line of this document contains the word "Disto.," which is short-hand for "Districto" or "District." At first glance, it would seem that "Disto." reads "Osito" [i.e., little bear] but this word does not fit within the context of the sentence, which has to do with the Royal Corporation. Further, the word in question becomes clearer when one realizes that it was acceptable to use abbreviations in the nineteenth century. Therefore, in attempting to translate documents, I have found that contextualization can be of significant help in deciphering unknown or ambiguous words."

This example illustrates the importance of referring to the original yourself when working closely with a document. If a casual translator interpreted the word as "little bear," imagine how different the letter would seem! It's a good idea to check any unusual words or phrases against the original - you may know more about the context in which the document was written and than whomever translated it.