Chapter 45: Precious Freedom

Before the troop of happy students reached the end of the meadow, they came to the track to the goat herder’s cabin, just where Farmer Koto said it would be, winding it’s way into the dense, dark forest on the eastern side of the meadow. After following the narrow track for several minutes, walking single-file with Mati and Tera in the lead, they came upon a huge old stump nestled in the trees beside a little stream.

As Mati rounded the massive tree stump, she first saw an irregular mossy roof, then little windows. Eventually a door came into sight, and on the far side she glimpsed a rock chimney. “It’s a house! It’s the most beautiful, magical house I’ve ever seen!”

Miko and Neti walked up to the house that was, to their eyes, very crude and cramped, little more than an animal burrow. They found a rope tied through the door handle. “No one’s home,” Miko announced.

As Boro arrived, he looked over the empty goat pen and shed in the yard, and other signs that they had, indeed, found the dwelling of a goatherd.

Everyone got comfortable on some fallen logs not far down the stream, and Buna handed out ripe plums.

“So, Ilika,” Boro began, resting his heavy rucksack on a log and slipping out of the straps, “the crew of your ship will have hard problems to solve, like the one we just did, but instruments and things will make it easier?”

“Much easier. But we’ll sometimes pretend something is broken, just for practice.”

“What if . . .” Miko pondered out loud with a soul-searching look on his

NEBADOR BookTwo: Journey 246

face, “there’s a real emergency . . . and someone makes a big mistake, a dangerous mistake?”

“Just like with anything in life, Miko, we scramble to fix it if we can. If we can’t, well . . .”

There was a long moment of silence as others nodded, even though Ilika hadn’t finished his sentence. Miko continued to quietly wrestle with some very personal feelings.

“I’ve heard that . . . lots of ship hands . . . die on long voyages,” Toli said with a shaking voice.

“Not where I come from!” Ilika assured them. “The ships in your harbor can sink very easily. The crews have miserable living conditions, bad food, no medical care, and terrible leadership. Misa would make a better captain than some . . .”

The girl grinned proudly.

“But in the Transport Service, the death of a crew member is very rare.

Also, long voyages are rare. My ship is fast, so most trips will take just a few hours, at most a few days.”

Miko and Toli both looked happier.

A thoughtful look came to Neti. “I think we should pick a new emergency meeting place.”

“Good idea,” Ilika said and pulled out the map as everyone gathered around. “We are here, at the north end of the big meadow, this area on the map with no trees. Before we cross the first mountain pass, here, our meeting place will be Koto’s farm. After the pass . . . it will be the village in the middle of the mountains.”

NEBADOR BookTwo: Journey 247

“Is that a monastery of a religious order?” Buna questioned with a frown.

“It’s not the same order that gave us trouble. From what little I’ve heard, it’s a very secretive order that doesn’t get mixed up in politics.”

Buna sighed with relief. “That’s good.”

Soon they began to hear the sounds of goats coming through the trees from the meadow, a herding dog nipping at their heels. The sounds continued and grew louder as the animals approached their home.

Eventually the dog sensed the strangers and broke off his work. He placed himself between the house and the group, snarling.

Finally a young man about Ilika’s age came into view, a worried look on his face. With each step, he let his long walking stick take most of his weight on one side. Arriving at the far bank of the stream, he stood beside his faithful dog and looked down at the strangers with cautious eyes peering out from under wild, tangled hair. After a few moments, he relaxed. “It’s alright, Sam, they look harmless.”

“We are,” Ilika said, still seated.

The young goatherd, with the help of his dog, coaxed the fifty or more goats into their pen. After hobbling by his house to glance at the knot securing his door, he returned to the stream. “What brings you to my home, strangers?”

“We stayed with Farmer Koto last night and bought some supplies. Now we’re looking for a rucksack for this young lady to carry her blankets . . .”

Misa waved shyly.

“Koto said you might have one you could sell us.”

“Hmm. I might.”

“Also, maybe some hard cheese if you’ve got too much.”

The goatherd looked at each member of the group, then limped back to his house, untied the knot, and disappeared inside. He returned a few minutes later with a rucksack. “It’s small, so I don’t use it much, but it might be okay for the girl.”

Ilika examined the sack — old but sturdy. He handed it to Misa, who looked it over, then stuck her head inside. When she came back out, she was smiling.

NEBADOR BookTwo: Journey 248

Kibi noticed the goatherd looking at Mati the entire time.

“What will you sell it for?” Ilika asked.

The young man pulled his attention from Mati with an effort. “You tell me what it would cost in town.”

“You mean the town that burned up?” Buna asked with a twisted smirk.

“I heard about that. It’s gonna be a long trip for supplies until they rebuild.”

“At Port Town,” Ilika began, “I’d pay seven coppers for it. But since we’re way up here in the woods, I’ll give you a silver.”

“Done!” the goatherd said quickly to seal the deal.

Ilika dug the coin out of his pouch.

The young handicapped man looked at Mati again while he spoke. “I think I’ve got three or four fully-cured cheeses in my cellar . . .”

“Your magical house has a cellar too?” Mati asked with wide eyes, looking directly at him for the first time.

Their eyes met and time stood still for both of them.

“Um . . . yes,” the goatherd managed to say, finally remembering the question but not taking his eyes from Mati. “Way up here in the woods we smoke meat, press cheese, dry fruit, and gather whatever we can from the forest, so a cellar is important. It’s already late,” he went on, reluctantly looking at the others, “so you’re welcome to camp here and make a fresh start in the morning.”

Ilika nodded. “Thank you. Tomorrow we head for the mountain pass.”

With an effort of will, the goatherd turned and hobbled toward his house.

As the group made camp among the fallen logs, the other students quickly noticed that Mati’s head was elsewhere. She spent most of her time looking at the little house in the old tree stump, and very little time caring for Tera, or helping with the camp. Rini made sure Tera had everything she needed.

Soon Boro had a fire going, and Neti started soup. Miko brought in armloads of wood, and Sata assembled their bags of dried herbs and spices on a log for Neti.

When they were about to eat, the goatherd appeared with a big wedge of cheese on a board. As the twelve of them began passing around bowls of

NEBADOR BookTwo: Journey 249

steaming soup, chunks of bread, and sticks of cheese, the setting sun sent farewell shafts of orange light into the clearing for a few minutes.

“I found four small wheels of well-aged cheese,” the goatherd said as he finished his soup, some of which had gotten into his wild hair. “But one thing that’s in very short supply up here in the mountains is . . . young ladies who will even look at a man who . . . doesn’t walk too well. If you’d let me talk to the beauty here who has the same problem I do, I’d sure appreciate it.”

A tense silence came over the group.

Ilika had to swallow before he could speak. “She’s not mine to say what she can or can’t do. She belongs to herself.”

“Would you like to talk, pretty lady? Maybe . . . check on the goats with me?”

To the surprise and frustration of all her friends, Mati sat grinning from ear to ear, and a moment later nodded.

The handsome brown-eyed goatherd rose, took a moment to steady himself with his walking stick, then held his hand out for Mati. With his help, she got her crutch under her and they slowly hobbled together toward the goat pen.

“You and me could be happy out here, me tending the goats, you keeping the house. You could ride your donkey when we go to town. Koto lets me borrow one of his horses . . .”

“Ilika!” Neti whispered loudly once the handicapped pair was gone. “You have to stop him!”

Ilika looked back at Neti and frowned. “You have all questioned me, again and again, to be sure you are free. Are you, or are you not, willing to respect Mati’s freedom now that she might choose her own way?”

They all looked at the ground.

“We’re sorry,” Boro mumbled. “It’s just . . . hard to imagine heading up the trail and doing lessons without . . . Mati and Tera.”

“I know,” Ilika agreed softly.

Kibi gazed thoughtfully into the flames of the campfire while the others whispered their frustrations to each other and slowly got ready for bed.

About an hour later, the goatherd delivered Mati back to the camp. They said good-night tenderly, and Mati crawled into her bedroll quietly, as if

NEBADOR BookTwo: Journey 250

already in a dream.

The entire group was thoughtful, almost sullen, the following morning as porridge simmered over the fire. The night had been cold, and most of them still wore their cloaks. Misa sat wrapped in her blankets.

“Ilika, is Tera mine?” Mati asked suddenly. “I mean . . . if I decide to stay here, do I get to keep her? I’d give you back all the money in my pouch . . .”

Ilika hesitated for a second. “Yes, Mati, Tera is yours, completely yours.

And if you decide to stay, the coins in your pouch will be a gift from us.”

“But Mati, you can’t!” Buna burst out with a pleading tone.

Mati locked eyes with Buna and took a deep breath. “You guys have to understand . . . I was a crippled slave. I had no hope of any kind of life. Ilika gave me hope, and many other things. He says I have a chance to be on his crew, but I’m not stupid. I’m a cripple! What am I going to do on a ship, peel potatoes?”

Everyone else was stunned into complete silence by Mati’s words.

“I have never, in my entire life,” she went on, breathing hard, “had a man tell me he liked me, and wanted to share a home with me. I can’t walk away from the only man to ever say that, on the chance that four of you are going to die tomorrow so Ilika will have to pick me.”

In the silence that followed, Kibi put down her porridge and moved close to Mati on the log. “We’re friends, right?”

“Of course, Kibi.”

“Will you take a short walk with me before you make your decision?”

“Okay.”

With Kibi’s help, Mati stood up, took her crutch, and the two girls walked slowly to the far side of the goat shed.

Ilika looked much older and sadder as he watched Kibi and Mati walk away.

They found some old wooden boxes behind the shed and sat down.

“Mati, I just want to share some things I know are true.”

“Thanks, Kibi. You’ve always been honest with me.”

“And I’m going to be honest with you now, because it might be the last

NEBADOR BookTwo: Journey 251

chance I get. The absolute truth is, Mati, you have the same chance of being picked as I do.”

Mati’s eyes opened wide. “But you’re . . .”

“That’s right. And I know he’s going to pick you also, for a real place, not just for peeling potatoes. But he can’t tell us yet. It would ruin the group.”

“I know. He wants everyone to do their best.”

“And there’s a boy in our group who is dreaming of sharing a bed with you someday. He’s just not the kind of boy who’s going to blab about it until the time is right. He wouldn’t have faced that wolf for just anyone. He’s going to be on that crew too. You stay here, and you’ll never hear him say those words to you.”

Mati looked troubled.

“And if that isn’t enough to convince you,” Kibi continued, “then I want you to tell that goatherd all the things you know, all the things you can do, and see what happens.”

Kibi stood and walked back to the group alone.

Mati sat for another quarter hour, then made her way slowly back toward the camp, toward her teacher Ilika, toward her friend Kibi . . . and toward Rini. As she rounded the goat pen, the magical tree-stump house came into view. Just at that moment, the handsome young goatherd came out, walking stick in one hand, four small cheese wheels under his other arm. A resolute expression came to Mati and she hurried so she would arrive at the camp before him.

“I appreciate what you tried to do, Kibi, but I’m staying here. I can’t give up something real for things other people might do someday in the future if they happen to get around to it.”

“Ilika, aren’t you going to do something?” Buna spat out with frustration.

“No, Buna, I’m not. I’m not Mati’s master. If Mati, or any of you, truly needs my help, I’ll be there, to my last breath if necessary. But there’s nothing happening here Mati can’t handle.”

“But Mati, our group wouldn’t be the same without you!” Neti pleaded.

Miko, Toli, and Boro all mumbled agreements, but were unsure what else to say. Rini looked sad, but said nothing.

NEBADOR BookTwo: Journey 252

Buna stood up, red-faced, hands clenched into fists. “I won’t let him take you away from us!”

“Stop it! All of you!” Mati screamed. “I’m free, and I’ve decided. I’m staying here, and it’s time for you to go!”

The goatherd, hearing the entire argument as he approached, stepped beside Mati wearing a subtle smile.

Ilika slowly rose. “I wish you well, Mati. Like I said, Tera is yours, and the coins in your pouch are a gift from us. We will pack up and leave as soon as I pay for the cheese.”

Buna suddenly turned and ran down the path toward the meadow, shaking her fists and crying.

Rini just sat on a log looking at the ground.

Deep Learning Notes

What need in Mati might have caused her to see a magical house, where others saw a crude and cramped shack?

As they discussed ship emergencies, what feelings was Miko experiencing?

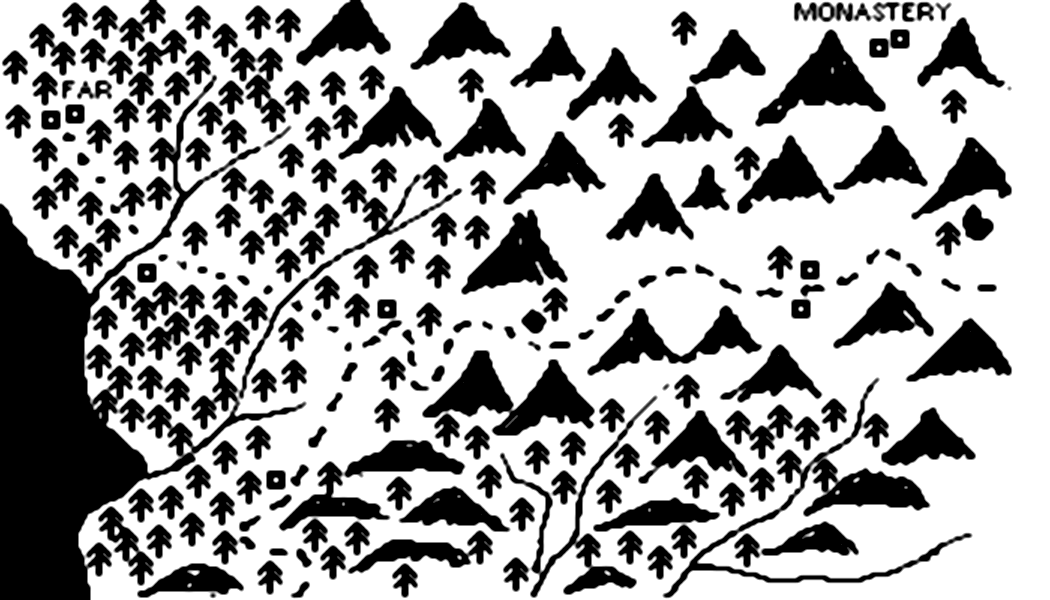

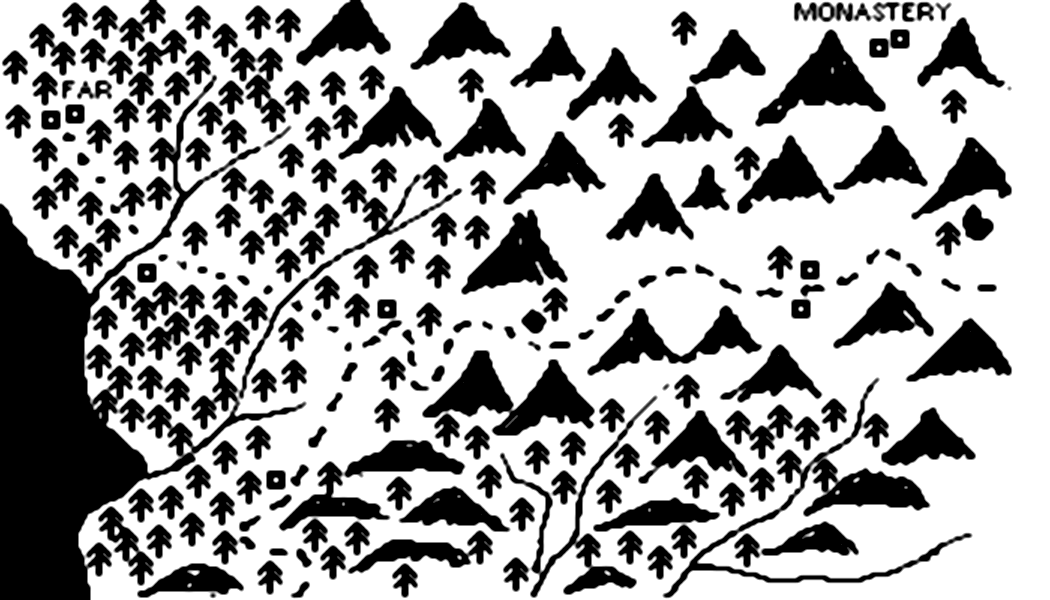

A map shows the western side of the mountains. The clear area surrounded by forest is the large meadow. Both Farmer Koto’s house and the shepherd’s cabin (seen in the next chapter) are marked.

Why did Ilika stay seated when the goatherd arrived?

The relationship between Mati and the goatherd was obviously not based on a long courtship and an intimate knowledge of each other’s personalities, values, and habits. It was based on what they could see in a few short hours, and was motivated by the hard, cold reality of their situations as handicapped people in a world where no allowances were made for such people. Anyone who disagrees with their decision may want to try harder to “see through their eyes and walk in their shoes.”

NEBADOR BookTwo: Journey 253

How, in your opinion, did Kibi know that Ilika would pick Mati to be on his crew? Do you believe Kibi was right?

What feelings might have motivated Buna to respond to the situation so dramatically?

Could Rini have done anything, during this chapter, to change the outcome?

NEBADOR BookTwo: Journey 254