CHAPTER 3

a) Respect for civil government v. 1-3

b) Salvation revealed by mercy & grace v. 4-7

c) Maintaining good works v. 8

d) Avoiding contentions, strivings, etc., v. 9-11

e) Final Greetings and Exhortations, v. 12-15

Conclusion

Did Paul write Hebrews?

It is possible Paul wrote the book of Hebrews. There are a

couple reasons why this might be the case.

First, in the earliest manuscript editions of the New Testament books, Hebrews is included after Romans among

the books written by the apostle Paul. This was taken as evidence that Paul had written it, and some Eastern churches

accepted Hebrews as canonical earlier than in the West.

Second, both Clement of Alexandria (c. AD 150 – 215) and

Origen (AD 185 – 253) claimed a Pauline association for the

book but recognized that Paul himself probably did not put

410

THE CHIEF

pen to paper for this book, even though they did not know

the author’s name.

Clement of Alexandria suggests that Paul wrote the book originally in Hebrew and that Luke translated it into Greek,

though the Greek of Hebrews bears no resemblance to

translation Greek (e.g., that of the Septuagint).

The King James Version assumes Pauline authorship

The nuanced position on the authorship question by the Alexandrian fathers was obscured by later church tradition

that mistook Pauline association for Pauline authorship.

The enormously influential King James Bible took its cue from this tradition. In fact, in the KJV, you’ll find the title translated as it was found in some manuscripts: “The Epistle

of Paul the Apostle to the Hebrews.” The tradition of Pauline authorship continued….

The most persuasive argument against Pauline

authorship

An even more persuasive argument that the apostle Paul was

not the author of Hebrews is the way the author alludes to

himself in Hebrews 2:3, stating that the gospel was

confirmed “to us” by those who heard the Lord announce salvation.

The apostle Paul always made the point that, even though he

wasn’t one of the twelve original disciples who walked with

Jesus during his earthly life, he was nonetheless an apostle

of Jesus Christ, and usually identifies himself as such in his letters. It seems unlikely that Paul here in 2:3 would refer to himself as simply someone who received the gospel from those who had heard the Lord.

411

THE CHIEF

With that, we close on the life of the Apostle Paul, the Chief of Sinners.

1.

https://insight.org/resources/bible/the-pauline-epistles/first-timothy 2.

Albert Garner, Power Bible CD, introduction to and outline of 1 Timothy 3.

https://blog.rose-publishing.com/2023/07/03/what-really-happened-to-paul-after acts/

4.

Albert Garner, Power Bible CD, introduction to and outline of 2 Timothy 5.

https://files.snappages.site/npkxonflbc/assets/files/Titus-Introduction-and-Chapter 1.pdf 412

THE CHIEF

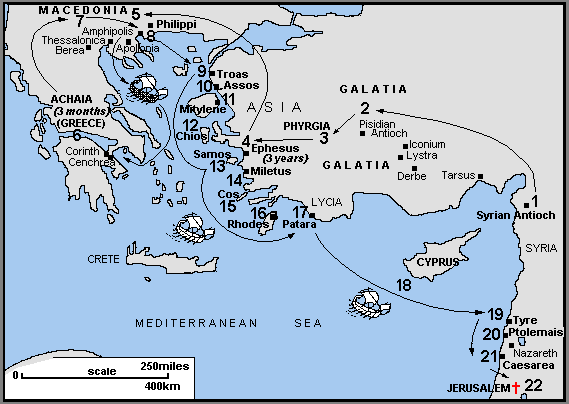

Appendix One

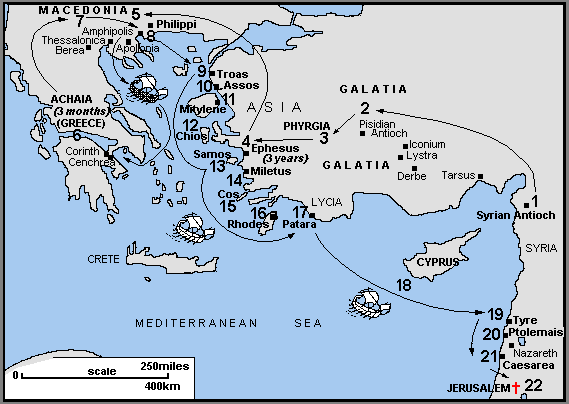

Ports of Call for Paul on his way to Jerusalem

An island off the coast of Caria, Asia Minor, one of the

Sporades, mountainous in the southern half, with ridges

extending to a height of 2,500 ft.; identified with the modern 413

THE CHIEF

Stanchio. It was famous in antiquity for excellent wine,

amphorae, wheat, ointments, silk and other clothing (Coae

vestes). The capital was also called Cos. It possessed a

famous hospital and medical school, and was the birthplace of Hippocrates (the father of medicine), of Ptolemy Philadelphus, and of the celebrated painter Apelles. The large plane tree in the center of the town (over 2,000 years old) is called "the tree of Hippocrates" to this day. The older capital, Astypalaea, was in the western part of the island, the later (since 366 B.C.) in the eastern part. From almost every point can be seen beautiful landscapes and picturesque views of sea and land and

mountain.

Cos was one of the six Dorian colonies. It soon became a

flourishing place of commerce and industry; later, like Corinth, it was one of the Jewish centers of the Aegean, as well as one of the financial centers of the commercial world in the eastern

Mediterranean.

https://bibleatlas.org/cos.htm

414

THE CHIEF

An island (and city) in the Aegean Sea, West of Caria, rough and rocky in parts, but well watered and productive, though at present not extensively cultivated. Almost one-third of the island is now covered with trees in spite of earlier deforestation. The highest mountains attain an altitude of nearly 4,000 ft. The older names were Ophiusa, Asteria, Trinacria, Corymbia. The capital in

antiquity was Rhodes, at the northeastern extremity, a strongly 415

THE CHIEF

fortitled city provided with a double harbor. Near the entrance of the harbor stood one of the seven wonders of the ancient world-a colossal bronze statue dedicated to Helios. Tiffs colossus, made by Chares about 290 B.C., at a cost of 300 talents (300,000 in 1915), towered to the height of 104 ft.

In the popular mind-both before and after Shakespeare

represented Caesar as bestriding the world like a colossus-this gigantic figure is conceived as an image of a human being of

monstrous size with leas spread wide apart, at the entrance of the inner harbor, so huge that the largest ship with sails spread could move in under it; but the account on which this conception is based seems to have no foundation.

The statue was destroyed in 223 B.C. by an earthquake. It was restored by the Romans. In 672 A.D. the Saracens sold the ruins to a Jew. The quantity of metal was so great that it would fill the cars of a modern freight train (900 camel loads).

https://bibleatlas.org/full/rhodes.htm

416

THE CHIEF

A coast city of ancient Lycia, from which, according to Acts

21:1, Paul took a ship for Phoenicia. Because of its excellent harbor, many of the coast trading ships stopped at Patara,

which therefore became an important and wealthy port of entry to the towns of the interior. As early as 440 B.C. autonomous coins were struck there; during the 4th and the 3rd centuries the coinage was interrupted, but was again resumed in 168

B.C. when Patara joined the Lycian league. Ptolemy

Philadelphus enlarged the city, and changed its name to

417

THE CHIEF

Arsinoe in honor of his wife. The city was celebrated not only as a trading center, but especially for its celebrated oracle of Apollo which is said to have spoken only during the six winter months of the year. Among the ruins there is still to be seen a deep pit with circular steps leading to a seat at the bottom; it is supposed that the pit is the place of the oracle. In the history of early Christianity, Patara took but little part, but it was the home of a bishop, and the birthplace of Nicholas, the patron saint of the sailors of the East. Though born at Patara, Nicholas was a bishop and saint of Myra, a neighboring Lycian city, and there he is said to have been buried. Gelemish is the modern name

of the ruin. The walls of the ancient city may still be traced, and the foundations of the temple and castle and other public

buildings are visible. The most imposing of the ruins is a

triumphal arch bearing the inscription: "Patara the Metropolis of the Lycian Nation."

https://bibleatlas.org/full/patara.htm

418

THE CHIEF

An island situated near the Northeast corner of the Levant, in an angle formed by the coasts of Cilicia and Syria. In the Old Testament it is called Kittim, after the name of its Phoenician capital Kition.

The island is the largest in the Mediterranean with the exception of Sardinia and Sicily, its area being about 3,584 square miles. It lies in 34

degrees 30'-35 degrees 41' North latitude and 32 degrees 15'-34 degrees 36' East longitude, only 46 miles distant from the nearest point of the Cilician coast and 60 miles from the Syrian. Thus from the northern shore of the island the mainland of Asia Minor is clearly visible and Mt.

Lebanon can be seen from Eastern Cyprus. This close proximity to the Cilician and Syrian coasts, as well as its position on the route between 419

THE CHIEF

Asia Minor and Egypt, proved of great importance for the history and civilization of the island. Its greatest length, including the Northeast promontory, is about 140 miles, its greatest breadth 60 miles. The Southwest portion of Cyprus is formed by a mountain complex,

culminating in the peaks of Troodos (6,406 ft.), Madhari (5,305 ft.), Papofitsa (5,124 ft.) and Machaira (4,674 ft.). To the Northeast of this lies the great plain of the Mesorea, nearly 60 miles in length and 10 to 20

in breadth, in which lies the modern capital Nicosia (Lefkosia). It is watered chiefly by the Pediaeus (modern Pedias), and is bounded on the North by a mountain range, which is continued to the East-Northeast in the long, narrow promontory of the Karpass, terminating in Cape Andrea, the ancient Dinaretum. Its highest peaks are Buffavento (3,135

ft.) and Hagios Elias (3,106 ft.). The shore-plain to the North of these hills is narrow, but remarkably fertile.

n the life of the early church Cyprus played an important part. Among the Christians who fled from Judea in consequence of the persecution which followed Stephen's death were some who "travelled as far as Phoenicia, and Cyprus" (Acts 11:19) preaching to the Jews only. Certain natives of Cyprus and Cyrene took a further momentous step in preaching at Antioch to the Greeks also (Acts 11:20). Even before this time Joseph Barnabas, a Levite born in Cyprus (Acts 4:36), was prominent in the early Christian community at Jerns, and it was in his native island that he and Paul, accompanied by Barnabas nephew, John Mark, began their first missionary journey (Acts 13:4). After landing at Salamis they passed "through the whole island" to Paphos (Acts 13:6), probably visiting the Jewish synagogues in its cities. The Peutinger Table tells us of two roads from Salamis to Paphos in Roman times, one of which ran inland by way of Tremithus, Tamassus and Soil, a journey of about 4 days, while the other and easier route, occupying some 3 days, ran along the south coast by way of Citium, Amathus and Curium.

Whether the "early disciple," Mnason of Cyprus, was one of the converts made at this time or had previously embraced Christianity we cannot determine (Acts 21:16). Barnabas and Mark revisited Cyprus later (Acts

15:39), but Paul did not again land on the island, though he sighted it when, on his last journey to jerus, he sailed south of it on his way from Patara in Lycia to Tyre (Acts 21:3), and again when on his journey to 420

THE CHIEF

Rome he sailed "under the lee of Cyprus," that is, along its northern coast, on the way from Sidon to Myra in Lycia (Acts 27:4). In 401 A.D.

the Council of Cyprus was convened, chiefly in consequence of the efforts of Theophilus of Alexandria, the inveterate opponent of Origenism, and took measures to check the reading of Origen's works.

The island, which was divided into 13 bishoprics, was declared autonomous in the 5th century, after the alleged discovery of Matthew's Gospel in the tomb of Barnabas at Salamis.

https://bibleatlas.org/full/cyprus.htm

https://www.ccel.org/bible/phillips/CN245ACTSPaulsReturn.htm

Appendix Two

When was Hebrews written, and why

does it matter?

Bert Watts – August 29, 2022

One common argument against Christianity is that the church didn’t decide that Jesus was divine until much, much later. Run a quick Google search of 421

THE CHIEF

“When did the church decide that Jesus was God?” and you will read that

“different views would be debated for centuries by Christians” but that they

“finally settled on the idea that he was both fully human and fully divine by the middle of the 5th century in the Council of Ephesus.”

Similarly, many today parrot the belief made popular by author Dan Brown, who in his bestselling fiction book, The Da Vinci Code, made the claim that Jesus wasn’t considered divine until A.D. 325 at the Council of Nicea, and even then it was only for the political

purposes of the emperor Constantine. As a counter to that argument, we should consider the book of Hebrews, and we should consider when the book of Hebrews was written.

The Divinity of Jesus in Hebrews 1

First, it is clear that Hebrews makes the claim that Jesus is divine. Consider just the first chapter of the book. Hebrews 1 declares that:

• Jesus was the agent at work in creation and therefore existed prior to creation (Hebrews 1:2, 10 );

• Jesus shares the full nature of God (Hebrews 1:3);

• Jesus “upholds the universe by the word of his power” (Hebrews 1:3 );

• Jesus is the Son of God (Hebrews 1:2, 5);

• Jesus is worthy of worship, which is reserved for God alone (Hebrews 1:6; cf. Exodus 20:3; Isaiah 42:8);

• God uses the name “God” in reference to “the Son” (Hebrews 1:8);

• Jesus is eternal (Hebrews 1:12).

Hebrews teaches that Jesus is the God-Man. Fully divine. Fully human. So now the question is, when was Hebrews written?

The Date of Hebrews

There are four key pieces of evidence in determining the date of Hebrews.

Second-Generation Christians

First, we do know that some time has passed since Christ’s resurrection and 422

THE CHIEF

ascension. Hebrews 2:3 tells us that this group is a second-generation group.

They heard the gospel from those who heard from the Lord. On top of that, we know that they themselves have been believers in Christ for at least long enough that they should be well-versed in the faith (Hebrews 5:12; cf.

10:32).

The Suffering of Roman Christians

That helps us somewhat with the front-end of the dating process, but there is other evidence that can get us even closer. The second clue to consider is twofold. First, it seems likely that the letter was written to believers in Rome. In Hebrews 13:24, the author informs his audience that “those who are from Italy send you greetings.” The most natural understanding here is that believers who had left Rome were sending their greetings back to believers who they knew who still lived in Rome. With that in mind, part two of this piece of evidence is found in Hebrews 10. In verse 32, the writer asks the readers to “recall the former days, when, after you were enlightened, you endured a hard struggle with sufferings,” and goes on to describe the abuse they received, including imprisonment and loss of property. They’ve suffered for their faith, they’ve lost property, experienced bloodshed for their faith (see 12:4, “you have not yet resisted to the point of shedding blood”). These facts are key.

In A.D. 49, the emperor Claudius expelled the Jews (and likely man Jewish Christians) from Rome due to a dispute regarding someone named

“Chrestus.” It is very likely that “Chrestus” is meant to refer to “Christos,”

and the dispute was between Jews and the now Jewish believers in Christ.

Many were expelled, some persecution ensued, but the severe time of persecution, which involved much bloodshed for Christians, did not begin until A.D. 65 under the reign of Nero. Therefore, we need a time when the readers can remember the earlier suffering, but prior to the intense suffering.

External Evidence

A third piece of evidence is from the letter now known as 1 Clement.

Written by the church father, Clement, this letter was written no later than 423

THE CHIEF

the first part of the second century (likely by A.D. 140), with some arguing for a date as early as A.D. 95-96. 1 Clement helps us by solidifying the back-end of the timeline. 1 Clement is known to borrow from the letter to the Hebrews, with William Lane writing that “it is broadly recognized that Clement was, in fact, literarily dependent upon Hebrews.”

Therefore, Hebrews could not have been written later than 1 Clement.

The Destruction of the Temple

Finally, helping us again with the back-end of the timeline, we need to consider the internal evidence of the letter itself. Hebrews speaks extensively about the sacrificial system and the Levitical priesthood, and in so doing the author assumes the ongoing practice of reason that’s important is that the Temple in Jerusalem was destroyed in A.D. 70. After that event, the practice of animal sacrifice ceased. If Hebrews was written after the destruction of the temple, it would seem that the author would make a completely different argument and include that event in his argumentation.

One scholar, conceding that this is an argument from silence, goes on to put it like this: “this silence is deafening!”

Conclusion

The evidence seems to show this: Hebrews was written sometime well after A.D. 49 and prior to A.D. 65. The best guess perhaps is the late 50’s to early 60’s. What that means is that by 25-30 years after Jesus’s resurrection and ascension, this is the commonly held belief of the early church. They didn’t have Twitter, or Wikipedia, or email. They didn’t have scholarly journals with wide readership or radio programs to disseminate information.

Information travel was slow. Painfully slow. But by 25 years after the fact, it was already widely taught that Jesus is divine. Why is that? Because that’s what the very first believers believed. Jesus is God in the flesh, who was.

crucified for our sins, was buried, was raised on the third day, and ascended into heaven. The first believers believed it. They spread the news. The earliest church believed it. You can believe it, too.

424

THE CHIEF

Jesus’s divinity wasn’t invented in the mid-fifth century. It wasn’t decided for political motive in A.D. 325. It’s an eternally true fact, revealed in Scripture, and is the foundation of our faith.

https://mountaincreekbc.org/when-was-hebrews

written/#:~:text=Conclusion,belief%20of%2

0the%20early%20church.

425

THE CHIEF

Appendix Three

Historical Background of Paul’s Final Imprisonment

August 14, 2017 by Derrick G. Jeter

On July 19, AD 64, a fire broke out in Rome, destroying ten of the city’s fourteen districts. The inferno raged for six days and seven nights,flaring sporadically for an additional three days. Though the fire probably started accidentally in an oil warehouse, rumors swirled that Emperor Nero had ordered the inferno so he could rebuild Rome according to his own liking.

Nero tried to stamp out the rumors—but to no avail. He then looked for a scapegoat. And since two of the districts untouched by the fire were disproportionally populated by Christians, he shined the blame to them.

Roman historian Tacitus tells the story:

But all human efforts, all the lavish gifts of the emperor, and the propitiations of the gods, did not banish the sinister belief that the conflagration was the result of an order. Consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace.

. . . Accordingly, an arrest was first made of all who pleaded guilty [of being Christians]; then, upon their information, an immense multitude was convicted, not so much for the crime of firing the city, as of hatred against mankind.1

The accusation that Roman Christians hated humanity likely took root in their refusal to participate in Rome’s social and civic life, which was intertwined with pagan worship. Whether for that reason or for the fire, once Nero’s madness inflamed, he continued his persecution of Rome’s Christians. And as a “ringleader” (Acts 24:5), Paul was rearrested at some point and placed, according to church tradition, in the Mamertine Prison.

The Mamertine Prison could have been called the “House of Darkness.”

426

THE CHIEF

Few prisons were as dim, dank, and dirty as the lower chamber Paul occupied. Known in earlier times as the Tullianum dungeon, its “neglect, darkness, and stench” gave it “a hideous and terrifying appearance,”

according to Roman historian Sallust. 2

Prisoners in the ancient world were rarely sent to prison as punishment.

Rather, prisons typically served as holding cells for those awaiting trial or execution. We see this throughout Scripture. Mosaic Law made no provision for incarceration as a form of punishment. Joseph languished in an Egyptian prison for two years, presumably awaiting trial before Pharaoh on a charge of rape (Genesis 39:19–20; 41:1). Jeremiah was imprisoned under accusation of treason (Jeremiah 37:11–16) but was transferred to the temple guardhouse after an appeal to King Zedekiah, who sought to protect the prophet (37:17–21). And though Jeremiah was later thrown into a cistern, the purpose was to kill him, not imprison him (38:1–6).

During Paul’s first imprisonment, he awaited trial before Roman governors Felix and Festus (Acts 24–26). He then was under house arrest in Rome for two years (28:30), awaiting an appearance before Nero. Scholars believe Paul was released sometime in AD 62 because the Jews who had accused him of being “a real pest and a fellow who stirs up dissension” (24:5) didn’t press their case before the emperor. However, during Paul’s second imprisonment in the Mamertine dungeon, he had apparently received a preliminary hearing and was awaiting a final trial (2 Timothy 4:16). He didn’t expect acquital; he expected to be found guilty, in all likelihood, for hating humankind. From there, Paul believed only his execution would be left (4:6–7), which was probably carried out in AD 68.3

1. Tacitus, Annals, 15.44, in Annals, Histories, Agricola, Germania, trans.

Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb (New York: Alfred A.

Knopf, 2009), 353–4.

2. Sallust, The War with Catiline, 55.5, Jugurthine, trans. J. C. Rolfe, rev.

John T. Ramsey (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2013), 133.

427

THE CHIEF

3. Paul must have languished in the Mamertine Prison for a couple of years before his beheading (as befitting his status as a Roman citizen), which, according to tradition, occurred on the Ostian Way about three miles outside the city. Eusebius notes that Paul and Peter were executed during the same Neronian persecution, though Peter was crucified upside down, as he requested. See Eusebius, The Ecclesiastical History, vol. 1, 2.25.6, 8 and 3.1.2, trans. Kirsopp Lake (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1926), 181, 183, 191. Copyright © 2009, 2015, 2017 by Charles R.

Swindoll, Inc. All rights are reserved worldwide. Used by permission. For additional information and resources visit us at www.insight.org.

https://insight.org/resources/article-library/individual/historical background-of-paul-s-final-imprisonment

428

THE CHIEF

About the Author

Dr. Joseph F. Roberts has been a Baptist minister, missionary, and pastor for over 56 years. He currently serves as Executive Director of the International Missionary Baptist Ministries, a ministry of the Mayfield Drive Baptist Church in Smyrna, Tennessee. He holds two Bachelor of Theology Degrees, a Master of Theology Degree, a Master of Divinity Degree, a Doctor of Theology Degree, and a Doctor of Philosophy in Religion Degree. He is a published author of several books and articles.

429

THE CHIEF

Other Books by This Author

The Lord’s Prayer

Church History Through the Trail of Blood

The Birth of Christ

A Sin Unto Death (Edited by Author)

The Footsteps of Jesus

Cardinal Doctrines of a New Testament Church

The Prayers of Jesus

How to Be: Humble, Joyful…

How to Go to Heaven: What Must I Do to Be Saved?

First, Second, Third John (Edited by Author)

Christianity in Action (Edited by Author)

Understanding the Holy Spirit

The Church Covenant (Edited by Author)

430

THE CHIEF

431

THE CHIEF

No doubt there are hundreds of books, articles,

and eBooks that have been written about the life of

the Apostle Paul. Despite all the work that has been

written on the subject, there is always room for more

on Paul. He is such an outstanding figure, we never

tire to expound on the life of a man whose beliefs

and actions have caused him rise to the top of the

list, to be one of the most ancient men to come to

the top of human history, other than Jesus Himself.

The lessons to be learned from his life and his

teachings can be compared to a well of knowledge

whose depths cannot be reached. Yet at the same

time he calls himself the chief of sinners. Why

would we want by any reasonable notion to consider

the work of a man who thought of himself in that

manner? We will see.

432