Chapter Forty-Eight

The Chief

The Final Years

Philemon 22 KJV But withal prepare me also a lodging: for I trust that

through your prayers I shall be given unto you.

Introduction

As we can see from our text verse, Paul believed that he would be released from house arrest and be freed. No one had arrived from Jerusalem or Judah to present their case against him before Ceasar, and the two-year time frame was beginning to draw to a close. Therefore, his request for Philemon to prepare a place for him to stay for a bit.

There is not much biblical proof of Paul’s actions after he is set free, or even that he was set free. We are dependent upon what historical scraps and traditions that we can find to get an idea about what he did. When it comes to tradition, we are aware that it may or may not be what the actual truth is.

Therefore, we are bound to give this caveat, “according to tradition.” This means that we are not sure what the actual events were, but this is what is believed by the most knowledgeable among mankind.

We are forced to use outside sources for what we can glean concerning Paul’s life after these two years.

Paul’s Release

Paul's First Imprisonment in Rome (Acts 28:30-31, 60-62

AD)

Paul is under house arrest in Rome. "Paul was allowed to live by himself, with a soldier to guard him." (Acts 28:16).

387

THE CHIEF

But within these constraints, he is free to conduct his ministry in person and by letter. The book of Acts concludes:

"30 For two whole years Paul stayed there in his own rented house

and

welcomed

all

who

came

to

see

him. 31 Boldly[448] and

without

hindrance[449] he

preached[450] the kingdom of God and taught[451] about

the Lord Jesus Christ." (Acts 28:30-31)

For these two years, he is chained to a Roman guard, one of

several who rotate through shifts. As a result, over time, many soldiers are converted. If Philippians was written during Paul's Roman imprisonment (as I think likely), then

he not only had a letter-writing ministry, but also a personal ministry to those around him.

"As a result, it has become clear throughout the whole palace guard and to everyone else that I am in chains for Christ."

(Philippians 1:13)

But in spite of the inconvenience of being chained to a guard, Paul carries on a rather active ministry, with many people coming and going. This is how the Acts of the Apostles ends:

Paul is in the heart of the Roman Empire, declaring the gospel openly, with the full knowledge of the Roman

government -- a victory!

10.3. Paul's Release in 62 AD

Presumably Paul would have had a hearing before Caesar (Acts 27:24) at the end of this period. The possible results

might be: (1) conviction and execution, (2) conviction and

much stricter confinement, (3) exile from Rome, or (4) Paul's accusers

don't

appear

and

his

case

is

dismissed.[452] Perhaps the significance of the "two years"

of Acts 28:30 is that it is the statutory time that Paul's 388

THE CHIEF

accusers have to bring their case before the emperor before

the case is dismissed. We're not sure.[453]

At any rate, there seems to be a firm Christian tradition that Paul was released for a time before his final execution.

Eusebius, writing around 300 AD says:

"After pleading his cause, he is said to have been sent again upon the ministry of preaching."[454]

Jerome writes in 392 AD, that at the end of his first imprisonment,

"Paul was dismissed by Nero, that the gospel of Christ might be preached also in the West."[455]

I think Paul's release in 62 AD is likely. If, as Christian tradition holds, Paul is executed by Nero following the great fire in Rome (64 AD, which we'll discuss in a moment), then

Paul has at least two years unaccounted for, from 62 to 64

AD, and perhaps more.

Paul's Ministry from 62 to 64 AD

What is Paul doing after his supposed release from prison in

62 AD? Here it gets pretty fuzzy, since there are only hints

in the New Testament, and specifics in early Christian tradition are rather general -- and sometimes conflicting.

389

THE CHIEF

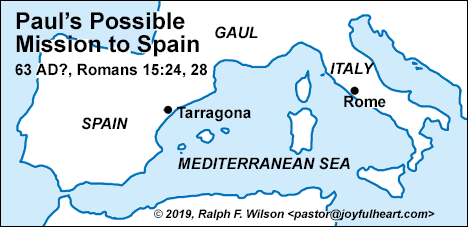

Map: Paul's Possible Mission to Spain (63 AD?, Romans 15:24, 28).

(larger map)

Ministry in Spain. One tantalizing possibility is that Paul goes to Spain, and preaches there in fulfillment of his wish

expressed in Romans 15:24, 28. Clement, bishop of Rome

88-99 AD, says:

"After preaching both in the east and west, he gained the illustrious reputation due to his faith, having taught righteousness to the whole world, and come to the extreme

limit of the west, and suffered martyrdom under the prefects" [or "given his testimony before the rulers"].[456]

The "extreme limit of the west" probably indicates Spain.

There

is

evidence

of

early

Christian

work

in

Spain.[457] This is also supported by the Muratorian Canon

(170 AD). The apocryphal Acts of Peter, a gnostic work dated about 180 AD, provides some detail about St. Paul departing to Spain from the Roman harbor of Ostia.[458] As

capital of the Roman province of Spain, Tarragona would have been the most likely city for Paul's mission to Spain,

390

THE CHIEF

and there are some late traditions in that city that support this scenario.[459]

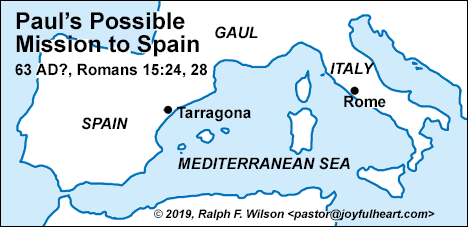

Map: Paul's Aegean Ministry following his first Roman imprisonment (62-65 AD). (larger map)

Ministry Around the Aegean Sea. The Pastoral Epistles (1

and 2 Timothy, Titus) seem to have been written after Paul's

Roman imprisonment, and offer some tantalizing clues to Paul's activities.[460] We're not sure of Paul's location when he writes 1 Timothy and Titus (though 2 Timothy is written

391

THE CHIEF

from prison in Rome at the end of his life[461]). Here are some snippets that suggest a ministry around the Aegean Sea:

"As I urged you when I went into Macedonia, stay there in Ephesus so that you may command certain men not to teach

false doctrines any longer" (1 Timothy 1:3)

"Although I hope to come to you [in Ephesus] soon, I am writing you these instructions so that, if I am delayed...." (1

Timothy 3:14-15)

"The reason I left you in Crete was that you might straighten out what was left unfinished and appoint elders in every town, as I directed you." (Titus 1:5)

"As soon as I send Artemas or Tychicus to you, do your best to come to me at Nicopolis, because I have decided to winter there." (Titus 3:12)

"When you come, bring the cloak that I left with Carpus at Troas, and my scrolls, especially the parchments." (2

Timothy 4:13)

"Erastus stayed in Corinth, and I left Trophimus sick in Miletus." (2 Timothy 4:20)

Exactly where Paul goes and when is a mystery we can't unravel. But it seems to me that probably Paul went to Spain

and conducted a ministry in the Aegean area from about 62

to 64 or 65 AD.

10.4. Paul's Final Days and a Christian View of Death

Rome Burns; Christians Are Blamed

Now an event occurs that has a major impact on the Christian

movement -- especially in Rome. Rome burns! On the night

392

THE CHIEF

of July 18-19, 64 AD a fire begins in the region of the Roman circus and consumes half the city before it is brought under

control after six days. Various stories circulate about its cause. Several have Nero responsible. Some record him

playing his lyre as he watches the fire. Others have him out

of

town

in

Antium.

Others

credit

it

to

an

accident.[462] Roman historian Tacitus tells us that after the fire, Nero brings in food supplies and opens places to accommodate the refugees. Of Rome's fourteen districts

only four remain intact. Three are leveled to the ground. The other seven are reduced to a few scorched and mangled ruins.

It is a terrible tragedy! But then it gets blamed on the Christians. According to Roman historian Tacitus (56-120

AD), the public believes that the fire is the result of an order by Nero. Here is Tacitus's conclusion, penned about 117 AD:

"Consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace.

Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the

extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of

one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus, and a most

mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment,

again broke out not only in Judaea, the first source of the evil, but even in Rome, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world find their center and

become popular.

Accordingly, an arrest was first made of all who pleaded guilty; then, upon their information, an immense multitude

was convicted, not so much of the crime of firing the city, as of hatred against mankind.

393

THE CHIEF

Mockery of every sort was added to their deaths. Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and

burnt, to serve as a nightly illumination, when daylight had

expired.

Nero offered his gardens for the spectacle, and was

exhibiting a show in the circus, while he mingled with the

people in the dress of a charioteer or stood aloft on a car.

Hence, even for criminals who deserved extreme and

exemplary punishment, there arose a feeling of compassion;

for it was not, as it seemed, for the public good, but to glut one man's cruelty, that they were being destroyed."[463]

Paul apparently isn't convicted by accusations of the Jews that brought him to Rome to be tried before Nero about 60-62 AD. But after the terrible fire that consumes much of Rome, anyone considered as a leader of the Christians in Rome would be subject to arrest and death, whether or not

he is a Roman citizen. We assume that Paul is arrested and

is in custody in Rome sometime in 64 or 65 AD.

The film, "Paul, Apostle of Christ" (2018, Sony Pictures), depicts with stark vividness the Christian community in Rome undergoing this horror. The film opens with Paul, condemned and confined in a dungeon underground in the

infamous Mamertine Prison in Rome. According to

tradition, prisoners were lowered through an opening into the lower dungeon.[464] Both St. Peter and St. Paul are imprisoned there, according to tradition.1

Here is another source.

On July 19, AD 64, a fire broke out in Rome, destroying ten

of the city’s fourteen districts. The inferno raged for six days and seven nights, flaring sporadically for an additional three 394

THE CHIEF

days. Though the fire probably started accidentally in an oil warehouse, rumors swirled that Emperor Nero had ordered

the inferno so he could rebuild Rome according to his own

liking. Nero tried to stamp out the rumors—but to no avail.

He then looked for a scapegoat. And since two of the districts untouched by the fire were disproportionally populated by Christians, he shifted the blame to them.

Roman historian Tacitus tells the story:

But all human efforts, all the lavish gifts of the emperor, and the propitiations of the gods, did not banish the sinister belief that the conflagration was the result of an order.

Consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. . . .

Accordingly, an arrest was first made of all who pleaded guilty [of being Christians]; then, upon their information, an immense multitude was convicted, not so much for the crime

of firing the city, as of hatred against mankind.(1)

The accusation that Roman Christians hated humanity likely

took root in their refusal to participate in Rome’s social and civic life, which was intertwined with pagan worship.

Whether for that reason or for the fire, once Nero’s madness

inflamed, he continued his persecution of Rome’s

Christians. And as a “ringleader” (Acts 24:5), Paul was rearrested at some point and placed, according to church tradition, in the Mamertine Prison.

The Mamertine Prison could have been called the “House of

Darkness.” Few prisons were as dim, dank, and dirty as the

lower chamber Paul occupied. Known in earlier times as the

Tullianum dungeon, its “neglect, darkness, and stench” gave

395

THE CHIEF

it “a hideous and terrifying appearance,” according to Roman historian Sallust. (2)

Prisoners in the ancient world were rarely sent to prison as

punishment. Rather, prisons typically served as holding cells for those awaiting trial or execution. We see this throughout Scripture. Mosaic Law made no provision for incarceration

as a form of punishment. Joseph languished in an Egyptian

prison for two years, presumably awaiting trial before Pharaoh on a charge of rape (Genesis 39:19–20; 41:1).

Jeremiah was imprisoned under accusation of treason

(Jeremiah 37:11–16) but was transferred to the temple

guardhouse after an appeal to King Zedekiah, who sought to

protect the prophet (37:17–21). And though Jeremiah was later thrown into a cistern, the purpose was to kill him, not imprison him (38:1–6).

During Paul’s first imprisonment, he awaited trial before Roman governors Felix and Festus (Acts 24–26). He then was under house arrest in Rome for two years (28:30), awaiting an appearance before Nero. Scholars believe Paul

was released sometime in AD 62 because the Jews who had

accused him of being “a real pest and a fellow who stirs up

dissension” (24:5) didn’t press their case before the emperor.

However, during Paul’s second imprisonment in the

Mamertine dungeon, he had apparently received a

preliminary hearing and was awaiting a final trial (2 Timothy 4:16). He didn’t expect acquittal; he expected to be found

guilty, in all likelihood, for hating humankind. From there,

Paul believed only his execution would be left (4:6–7), which was probably carried out in AD 68.(3)

1. Tacitus, Annals, 15.44, in Annals, Histories, Agricola, Germania, trans.

Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009), 353–4.

396

THE CHIEF

2. Sallust, The War with Catiline, 55.5, in The War with Catiline, The War with Jugurthine, trans. J. C. Rolfe, rev. John T. Ramsey (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2013), 133.

3. Paul must have languished in the Mamertine Prison for a couple of years before his beheading (as befitting his status as a Roman citizen), which, according to tradition, occurred on the Ostian Way about three miles outside the city. Eusebius notes that Paul and Peter were executed during the same Neronian persecution, though Peter was crucified upside down, as he requested. See Eusebius, The Ecclesiastical History, vol. 1, 2.25.6, 8 and 3.1.2, trans. Kirsopp Lake (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1926), 181, 183, 191.2

And yet another.

The Bible does not say how the apostle Paul died. Writing

in 2 Timothy 4:6–8, Paul seems to be anticipating his soon

demise: “For I am already being poured out as a drink offering, and the time of my departure has come. I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept

the faith. Henceforth there is laid up for me the crown of righteousness, which the Lord, the righteous judge, will award to me on that Day, and not only to me but also to all

who have loved his appearing.”

Second Timothy was written during Paul’s second Roman

imprisonment in AD 64—67. There are a few different

Christian traditions in regards to how Paul died, but the most commonly accepted one comes from the writings of

Eusebius, an early church historian. Eusebius claimed that Paul was beheaded at the order of the Roman emperor Nero

or one of his subordinates. Paul’s martyrdom occurred

shortly after much of Rome burned in a fire—an event that

Nero

blamed

on

the

Christians.

It is possible that the apostle Peter was martyred around the same time, during this period of early persecution of 397

THE CHIEF

Christians. The tradition is that Peter was crucified upside down and that Paul was beheaded due to the fact that Paul

was a Roman citizen (Acts 22:28), and Roman citizens were

normally

exempt

from

crucifixion.

The accuracy of this tradition is impossible to gauge. Again, the Bible does not record how Paul died, so there is no way

to be certain regarding the circumstances of his death. But,

from all indications, he died for his faith. We know he was

ready to die for Christ (Acts 21:13), and Jesus had predicted that Paul would suffer much for the name of Christ (Acts 9:16). Based on what the Book of Acts records of Paul’s life, we can assume he died declaring the gospel of Christ, spending his last breath as a witness to the truth that sets men free (John 8:32).3

Conclusion

For the final part, we will consider the writing of the books of 1 & 2 Timothy and Titus. If possible we will also take a short look at Hebrews.

1 https://www.jesuswalk.com/paul/10_prison.htm#_ftn464

2

https://insight.org/resources/article-library/individual/historical-background-of-paul-s-final-imprisonment

3 https://www.gotquestions.org/how-did-Paul-die.html

Note: Here are the references cited by the author of jesuswalk.com

[448] "Boldly" (NIV), "with all boldness" (ESV, NRSV), "with all confidence" (KJV) is two words, pas, "all," and parrēsia, "a state of boldness and confidence, courage, confidence, boldness, fearlessness," but here, the word carries something of "openness to the public," before whom speaking and actions take place," in our verse, "quite openly and unhindered" (BDAG 781, 3 and 2).

398

THE CHIEF

[449] "Without hinderance" (NIV, ESV, NRSV), "no man forbidding him" (KJV) is akōlytōs,

"without hinderance," found often in papyri as a legal technical term (BDAG 40). This is a compound verb, a-, "not" + kōlyō, "to hinder, prevent, forbid."

[450] "Preached" (NIV, KJV), "proclaiming" (ESV, NRSV) is kēryssō, "to make public declarations, proclaim aloud" (BDAG 543, 2bβ).

[451] "Taught" (NIV), "teaching" (ESV, NRSV, KJV) is didaskō, "to provide instruction in a formal or informal setting, teach" (BDAG 241, 2c).

[452] These are discussed by Bruce, Paul, p. 443-444.

[453] Bruce, Acts, pp. 534-535, cites William Ramsay, The Teaching of Paul (1913), pp. 346ff, but this seems more supposition than documented fact from Roman sources.

[454] Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, 2.22.2.

[455] Jerome, De Viris Illustribus ( On Illustrious Men), 5.

[456] 1 Clement 5.6-7.

[457] Irenaeus, Against Heresies 1.10.2; Tertullian, Answer to the Jews 7.

[458] See discussion of these in Bruce, Paul, pp. 449; E. E. Ellis, "Pastoral Epistles," DLP 661-662. 1 Clement 5:7; Acts of Peter (Vercelli) 1-3, 40; the Muratorian Canon; Eusebius, Church History 2.22.1-8.

[459] Otto F. A. Meinardus, "Paul's Missionary Journey to Spain: Tradition and Folklore," The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 41, No. 2 (Jun., 1978), pp. 61-63. Several late Spanish legends as earl as the 8th century describe his mission to the Catlans. John Chrysostom (398 AD) mentions, "Paul, after his residence in Rome, departed to Spain" ( Sermon on 2 Timothy 4:20). Jerome writes that the apostle reached Spain by sea.

[460] Though many scholars don't see the Pastoral Epistles as coming from Paul's hand, I accept them as genuine.

[461] 2 Timothy 1:17.

[462] "Great Fire of Rome," Wikipedia.

[463] Tacitus, Annals, 15.44.

[464] "Mamertine Prison," Wikipedia.

399

THE CHIEF