the two; another and another followed, until the entire family lay before

me, and a whole legion of jars covered the table and surrounding shelves;

the odor had become a pleasant perfume; and even now, the sight of an

old, six-inch, worm-eaten cork brings fragrant memories.

The whole group of haemulons was thus brought in review; and, whether

engaged upon the dissection of the internal organs, the preparation and ex-

amination of the bony framework, or the description of the various parts,

Agassiz’s training in the method of observing facts and their orderly ar-

rangement was ever accompanied by the urgent exhortation not to be con-

tent with them.

“Facts are stupid things,” he would say, “until brought into connection

with some general law.”

12

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 2. The Nature of Learning: Recognition of Different Perspectives

At the end of eight months, it was almost with reluctance that I left these

friends and turned to insects; but what I had gained by this outside ex-

perience has been of greater value than years of later investigation in my

favorite groups.4

Facts and Theories

And we may add to Agassiz’s statement, “General Laws are ‘stupid’ things

until brought into connection and interrelation with philosophical theo-

ries.”

Generally speaking, when we seek facts, we are not looking for objects

in the world, instead we are genuinely attempting to discover what is true

or what is the case about an event or an object. In other words, much

of the time, “fact” is used as a suitable paraphrase for “true statement.”5

Some of the time, however, facts are thought to be independent of a world

view since newly proposed theories not only can conform to some well-

established facts but also can imply the existence of hitherto unknown

facts. Whether or not such a view of the relation of facts to theories is

entirely true or not, it is true that many facts are dependent on theories

for their existence. Hence, it is somewhat simplistic to suppose one must

always seek facts in order to explain some puzzling state of affairs be-

cause what is the case or what is true is often theory-dependent. Some-

what surprisingly, we will discover that almost always our view of the

facts “changes” as the theories that imply them change.

Another way to illustrate the difficulties involved with just seeking the

facts in order to account for the way things are, is to realize that in any

given situation, we simply cannot collect all the facts, even though our

initial presumption is we should leave no stone unturned. For example, if

we were to try to explain how this page got in this book, we would not go

about seeking every related fact before we invoke possible theories of how

this “page-event” occurred. The number of facts concerning this page are

limitless.

4.

Samuel H. Scudder, “In the Laboratory With Agassiz”, Every Saturday, (April 4,

1974) 16, 369-370.

5.

Willard Van Orman Quine, Word and Object, Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press,

1960, 44.

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

13

Chapter 2. The Nature of Learning: Recognition of Different Perspectives

Specifically, it is a fact that each letter of each word is a specific distance

from any given letter of another word. Each letter is a measurable dis-

tance from any given object in the universe—for example, the distance to

a ballerina on a New York stage.6 The facts relevant to the state of affairs

described as “the page being in the book” increase and change over time

as the ballerina moves, and, of course, the facts change as we uncomfort-

ably fidget while considering the implications of this example. Therefore,

we are able to collect as many facts as we please and still not have them

all.

In order to make sense of a given state of affairs in the world, we must se-

lect only some of the facts—presumably, the relevant and important ones.

But how can we know beforehand which of the facts will be relevant and

important? We need some sort of criterion or rule for selection. In other

words, in order to find the relevant facts, we need a theory or at least a

few ruling assumptions involving what is appropriate in situations similar

to this one. We find out the specific relevant facts by applying a theory in

order to determine what facts we think should be considered in our expla-

nation. At this point our discussion may have become a bit too abstract for

an introductory philosophy reading. Perhaps, a specific example can clar-

ify by illustrating the point of what is meant by saying “facts are normally

theory-dependent.”

Facts Are Often Theory-Dependent

Suppose you and your astronomer-friend are camping along the

Appalachian Trail in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. As you

awake at dawn from the first sound of stirring wildlife, you sleepily

notice a rosy, picturesque sunrise.7 With a bit of alarm you anticipate

rain showers and a muddy hike ahead. As you rouse your friend, you

comment, “Look at that sunrise; we’re in for trouble.” Assume, moreover,

your friend dimly responds with a slow yawn, “I see the sun, but there is

no sunrise today or, for that matter, any day.”

6.

Newton’s law of gravitation is “Every object in the universe attracts every other

object with a force directed along the line of centers of the two objects that is propor-

tional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the

separation of the two objects.”

7.

“Red in the morning is a sailor’s sure warning.”

14

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 2. The Nature of Learning: Recognition of Different Perspectives

What do you say? Is your friend’s statement sensible? Presumably his eye-

sight is just as good as yours, and evidently he is looking where you are

looking. Yet, your friend is apparently claiming he does not see what you

see. You see the sunrise; he apparently is stating he does not. Now, is there

any chance you could be mistaken? Let’s pause just a moment and see if

this exchange makes any sense.

You do see the sun rising today, and you have seen it rise countless times

in the past. Your friend, however claims not only is there no sunrise today,

but there has never been a sunrise. Is this disagreement a misunderstanding

over the meaning of words, a misunderstanding due to personal feelings,

or a misunderstanding concerning relevant facts at hand? Also, assuming

we know what kind of dispute it is, how should we go about resolving it?

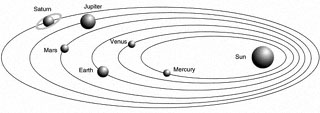

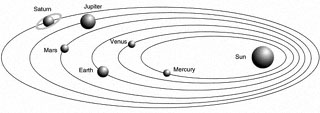

Sunrise in Smoky Mountains, Clingman’s Dome, NC

You would have to be a gentle person to think this far without suspect-

ing, perhaps in some exasperation, that your friend is half-asleep, does not

know what he is saying, or has some other kind of brain-trouble. However,

in order to make this disagreement a bit more interesting, let us further

suppose that your friend is beginning to warm up to the strange looks you

are giving him and proposes a bet. If you can convince him that the sun is

rising after all, he will prepare all meals and wash all utensils for the re-

mainder of the camping trip; if not, then you will prepare all the remaining

meals and wash the utensils.

Would you take the bet? Only a cursory look at the remains of the previous

night’s repast might be sufficient to convince you to accept the wager.

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

15

Chapter 2. The Nature of Learning: Recognition of Different Perspectives

After all, everybody knows the sun rises every morning whether we see

it or not.8 It is difficult to resist the payoff; you accept the bet and begin

thinking about proving your case.

From the reading. . .

“I see the sun, but there is no sunrise today. . . ”

On the one hand, how do you go about proving such an obvious and well-

known truism? If you proceed somewhat systematically, you might first

begin by getting clear and obtaining agreement about the meaning of any

key terms in the dispute. Most important, what does “sunrise” mean? Once

the significant terms are defined, then facts can be sought to verify the

hypothesis. Let us suppose your friend will reply something along the lines

of “sunrise” means “the usual daily movement above the eastern horizon

of the star which is the center of our solar system.” Second, you might

seek to show him that the facts correspond exactly to his definition. That

is, while eagerly anticipating his preparing of breakfast, you simply point

out the observation that the sun is rising above the horizon, as expected.

Finally, you could note that no undue feelings or attitudes have shaped

your position on this issue and cloud the judgments and observations of

either you or your friend, the other disputant.

On the other hand—let’s say you are beginning to be hungry—no telling

how long your dim-witted friend will hold out before admitting that he

actually does see the sun rising in the sky. O.K., the sun does move rather

slowly. Why not put the burden of proof on him? Let him prove that the sun

is not rising. We often take the approach of assuming we are right if our

beliefs cannot be disproved.9 Thus, here in the Blue Ridge Mountains you

8.

Note the argumentum ad populum.

9.

Note how this presumption, as well as the friend’s original bet could be viewed

as an example of an ad ignorantiam fallacy. If a statement or a point of view cannot be proved beyond a shadow of doubt, then that statement or point of view cannot

be known to be mistaken. The ad ignorantiam fallacy occurs whenever it is asserted that if no proof of a statement or argument exists, then that statement or argument

is incorrect. The error in reasoning is seen when we realize nothing can be validly

concluded from the fact that if you can’t prove something right now, then the opposite

view must be true.

16

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 2. The Nature of Learning: Recognition of Different Perspectives

put the question directly to your friend. “What could you possibly mean

by saying, ‘The sun doesn’t rise and isn’t rising right now’? Just look!”

Your friend sleepily replies, “Do Kepler and Tycho see the same thing in

the east as dawn?”10

Alas, you probably remember that Tycho Brahe, as well as most other

folks at the time, thought that the earth was the center of the heavens.

Kepler was one of the first persons to regard the earth as revolving around

the sun. If the earth moves around the sun, then it appears as though your

friend is correct. The sun does not really rise, the earth turns. Even worse,

he’s apparently right when he said the sun has never risen.

Doesn’t it seem that by now our culture would have this simple fact en-

trenched in our ordinary language? We do see the sun rise; we do believe

the sun rises. Aren’t these facts? Accordingly, both you and your friend do

not really have the same visual experience since your conceptual interpre-

tation of what you see differs from what he sees. Even though the patterns

of light and color are the similar for you and him, what you experience

is largely dependent on the theoretical perspective from which you view

the event. Just as we cannot know a foreign language only by listening, so

also we cannot know the sun rises only by seeing. It is not at all unusual

for two skilled investigators to disagree about their observations, if each is

interpreting the the data or “facts of the case” according to different con-

ceptual frameworks.11 Just as your mind-set affects what you see, so also

your awareness of other mental perspectives can affect what you know.

The learning of new perspectives is what, in large measure, philosophy is

all about.

From the reading. . .

“We find out the specific relevant facts by applying a theory in order

to determine what facts we think should be considered in our explana-

tion.”

10. For a detailed analysis of this question, see Norwood Russell Hanson’s Patterns

of Discovery, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1958, 5.

11. Frederick Grinnell. The Scientific Attitude. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1978, 15.

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

17

Chapter 2. The Nature of Learning: Recognition of Different Perspectives

Solar System, BNSC © HMG

Related Ideas

Project

Gutenberg

(http://www.ibiblio.org/gutenberg/etext04).

The

Project Gutenberg EBook of Louis Agassiz as a Teacher A compilation

by Lane Cooper of descriptions of Agassiz’s teaching methods by several

well known former students.

Topics Worth Investigating

1. What is a fact? What are the different kinds of facts? Can we be mis-

taken about the facts? Do facts change with new discoveries? Are

facts discovered or are they constructs of theories?

2. In the Philosophical Investigations, Ludwig Wittgenstein indicates

the aim of philosophy is “To shew the fly the way out of the

fly-bottle.”12 In what ways is this precisely the same problem facing

Samuel Scudder when he sits before Hæmulon elegans? What is the

difference between finding a method and using a method?

3. If the same state of affairs is seen from two different conceptual

frameworks, are there different facts involved? How can facts

implied by different theories be compared? Can one structurally

“translate” from theory to theory?

12. Ludwig Wittgenstein. Philosophical Investigations. New York: Macmillan, 1953,

§309.

18

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 3

The Nature of Philosophical

Inquiry

Ideas of Interest From “Nature of

Philosophical Inquiry”

Messier 81, NASA, JPL

1. How is philosophy provisionally defined in this chapter?

2. In what ways does Alexander Calandra’s “Barometer Story” illustrate

the philosophical approach to a practical problem? What do you think

is the difference between thinking about the methods for solving a

19

Chapter 3. The Nature of Philosophical Inquiry

problem and applying a method for solving a problem?

3. What are some of the differences between philosophy and science?

4. Briefly characterize the main branches of philosophy.

5. Do you think the kinds of distinct things that exist in the universe

are independent of the concepts we use for description? Consider the

following koans: “Where does my fist go when I open my hand?”

“Where does my lap go when I stand up?”

From the reading. . .

“. . . some people characterize a philosophical problem as any question

that does not have a well-established method of solution, but that defi-

nition is undoubtedly too broad.”

Characterization of Philosophy

One reasonably good beginning characterization of philosophy is that phi-

losophy is the sustained inquiry into the principles and presuppositions of

any field of inquiry. As such, philosophy is not a subject of study like other

subjects of study. Any given field of inquiry has philosophical roots and ex-

tensions. From the philosophy of restaurant management to philosophy of

physics, philosophy can be characterized as an attitude, an approach, or

perhaps, even a calling, to ask, answer, or even just comment upon certain

kinds of questions. These questions involve the nature, scope, and bound-

aries of that field of interest. In general, then, philosophy is both an activity

involving thinking about these kinds of ultimate questions and an activity

involving the construction of sound reasons or insights into our most basic

assumptions about the universe and our lives.

Quite often, simply asking a series of “why-questions” can reveal these

basic presuppositions. Children often ask such questions, sometimes to

the annoyance of their parents, in order to get a feel for the way the world

works. Asking an exhaustive sequence of “why-questions” can reveal prin-

ciples upon which life is based. As a first example, let us imagine the fol-

20

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 3. The Nature of Philosophical Inquiry

lowing dialogue between two persons as to why one of them is reading

this philosophy book. Samantha is playing “devil’s advocate.”

Samantha: “ Why are you reading Reading for Philosophical Inquiry?”

Stephen: “It’s an assigned book in philosophy, one of my college courses.”

Samantha: “Why take philosophy?”

Stephen: “Well, philosophy fulfills the humanities elective.”

Samantha: “Why do you need that elective?”

At this point in the dialog, a growing resemblance to the insatiable curios-

ity of some children is beginning to be unmistakable. We continue with

the cross-examination.

Stephen: “I have to fulfill the humanities elective in order to graduate.”

Samantha: “Why do you want to graduate?”

Stephen: “What? Well, I’d like to get a decent job which pays a decent

salary.”

Samantha:“Well, why, then, do you want that?”

Undoubtedly, at this point, the conversation seems artificial because for

some persons, the goal of graduating college is about as far as they have

thought their life through, if, indeed, they have thought that far—and so for

such persons this is where the questioning would have normally stopped.

Other persons, however, can see beyond college to more basic ends such

as Stephen’s want of an interesting vocation with sufficient recompense,

among other things. Even so, we have not yet arrived at the kind of ba-

sic presuppositions we have been talking about for Stephen’s life, so we

continue with Samantha’s questioning.

Stephen: “What do you mean? A good job which pays well will enable me

the resources to have an enjoyable life where I can do some of the important

things I want to do.”

Samantha: “Why do you want a life like that?”

Stephen: “Huh? Are you serious?”

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

21

Chapter 3. The Nature of Philosophical Inquiry

When questions finally seem to make no sense, very often, we have

reached one of those ultimate fundamental unquestioned assumptions. In

this case, a basic principle by which Stephen lives his life seems to be

based on seeking happiness. So, in a sense, although he might not be

aware of it at the moment, he believes he is working toward this goal

by reading this textbook. Of course, his choice of a means to obtain

happiness could be mistaken or perhaps even chosen in ignorance—in

which case he might not be able to obtain what he wants out of life. If

the thought occurs to you that it is sometimes the case that we might

not be mistaken about our choices and might actually be choosing

knowledgeably and even so might not achieve what we desire, then you

are already doing philosophy.

If we assume that Samantha is genuinely asking questions here and has

no ulterior motive, then it is evident that her questions relate to a basic

presupposition upon which Stephen is basing his life. Perhaps, she thinks

the quest for a well-paying job is mistaken or is insufficient for an excellent

life. Indirectly, she might be assuming that other fundamental values are

more important. If the questioning were to continue between Samantha

and Stephen, it quite possibly could go along the lines of attempting to

uncover some of these additional presuppositions upon which a life of

excellence can be based.

In philosophy these kinds of questions are often about the assumptions,

presuppositions, postulates, or definitions upon which a field of inquiry

is based, and these questions can be concerned with the meaning, signif-

icance, or integration of the results discovered or proposed by a field of

inquiry.1

For example, the answer “Gravity” is often thought to be a meaningful

answer to the question, “Why do objects fall in the direction toward the

center of the earth?” But for this answer to be meaningful we would have

to know what gravity is. If one were to answer “a kind of force,” or “ an

1.

Our

characterization

here

omits

what

are

sometimes

termed

the

“antiphilosophies” such as postmodernism, a philosophy opposing the possibil-

ity of objectivity and truth, and existentialism, a group of philosophies dismissing

the notion that the universe is in any sense rational, coherent, or intelligible. The

characterization of philosophy proposed in the text is provisional and is used as a

stalking horse for the discipline.

22

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 3. The Nature of Philosophical Inquiry

attraction” between two objects, then the paraphrase gives no insight into

the nature of what gravity is, for the paraphrase is viciously circular.

Many scientists hold the view that, “If we know the rules, we consider that

we ‘understand’ the world.”2 The rules for gravity are:

. . . every object in the universe attracts every other object with a force which

for any two bodies is proportional to the mass of each and varies inversely as

the square of the distance between them.

. . . an object responds to a force by accelerating in the direction of the force

by an amount that is inversely proportional to the mass of the object. . . 3

Yet, there must be more to understanding gravity than this. Consider a

mentalist who stands before a door and concentrates deeply. Suppose the

door opens, and no one, neither scientist nor magician, is able to see how

the mentalist accomplishes the opening of the door. So we ask, “How did

you do that?”

The mentalist responds, “Smavity.”

We reply, “What is ‘smavity’?”

The mentalist says, “Smavity is a force—an attraction between me and the

door.”

The scientist on the scene observes and measures:

The mentalist attracts the door with a force which b