assured, that their singular Passions, are parts of the Seditious roaring of a troubled Nation.

And if there were nothing else that bewrayed their madnesse; yet that very arrogating such

inspiration to themselves, is argument enough. If some man in Bedlam should entertaine you

with sober discourse; and you desire in taking leave, to know what he were, that you might

another time requite his civility; and he should tell you, he were God the Father; I think you

need expect no extravagant action for argument of his Madnesse.

This opinion of Inspiration, called commonly, Private Spirit, begins very often, from some lucky

finding of an Errour generally held by others; and not knowing, or not remembring, by what

conduct of reason, they came to so singular a truth, (as they think it, though it be many times

an untruth they light on,) they presently admire themselves; as being in the speciall grace of

God Almighty, who hath revealed the same to them supernaturally, by his Spirit.

Again, that Madnesse is nothing else, but too much appearing Passion, may be gathered out of

the effects of Wine, which are the same with those of the evill disposition of the organs. For the

variety of behaviour in men that have drunk too much, is the same with that of Mad-men:

some of them Raging, others Loving, others Laughing, all extravagantly, but according to their

severall domineering Passions: For the effect of the wine, does but remove Dissimulation; and

take from them the sight of the deformity of their Passions. For, (I believe) the most sober

men, when they walk alone without care and employment of the mind, would be unwilling the

vanity and Extravagance of their thoughts at that time should be publiquely seen: which is a

confession, that Passions unguided, are for the most part meere Madnesse.

The opinions of the world, both in antient and later ages, concerning the cause of madnesse,

have been two. Some, deriving them from the Passions; some, from Dæmons, or Spirits, either

good, or bad, which they thought might enter into a man, possesse him, and move his organs

in such strange, and uncouth manner, as mad-men use to do. The former sort therefore, called

such men, Mad-men: but the Later, called them sometimes Dæmoniacks, (that is, possessed

with spirits;) sometimes Energumeni, (that is, agitated, or moved with spirits;) and now in

Italy they are called not onely Pazzi, Mad-men; but also Spiritati, men possest.

There was once a great conflux of people in Abdera, a City of the Greeks, at the acting of the Tragedy of Andromeda, upon an extream hot day: whereupon, a great many of the spectators

falling into Fevers, had this accident from the heat, and from the Tragedy together, that they

did nothing but pronounce Iambiques, with the names of Perseus and Andromeda; which

together with the Fever, was cured, by the comming on of Winter: And this madnesse was

thought to proceed from the Passion imprinted by the Tragedy. Likewise there raigned a fit of

madnesse in another Græcian City, which seized onely the young Maidens; and caused many

of them to hang themselves. This was by most then thought an act of the Divel. But one that

suspected, that contempt of life in them, might proceed from some Passion of the mind, and

supposing they did not contemne also their honour, gave counsell to the Magistrates, to strip

such as so hang'd themselves, and let them hang out naked. This the story sayes cured that

madnesse. But on the other side, the same Græcians, did often ascribe madnesse, to the

operation of the Eumenides, or Furyes; and sometimes of Ceres, Phœbus, and other Gods: so

much did men attribute to Phantasmes, as to think them aëreal living bodies; and generally to

call them Spirits. And as the Romans in this, held the same opinion with the Greeks: so also

did the Jewes; For they called mad-men Prophets, or (according as they thought the spirits

good or bad) Dæmoniacks; and some of them called both Prophets, and Dæmoniacks mad-

men; and some called the same man both Dæmoniack, and mad-man. But for the Gentiles, 'tis

no wonder; because Diseases, and Health; Vices, and Vertues; and many naturall accidents,

were with them termed, and worshipped as Dæmons. So that a man was to understand by

Dæmon, as well (sometimes) an Ague, as a Divell. But for the Jewes to have such opinion, is

somewhat strange. For neither Moses, nor Abraham pretended to Prophecy by possession of a Spirit; but from the voyce of God; or by a Vision or Dream: Nor is there any thing in his Law,

Morall, or Ceremoniall, by which they were taught, there was any such Enthusiasme; or any

Possession. When God is sayd, Numb. 11. 25. to take from the Spirit that was in Moses, and give to the 70. Elders, the Spirit of God (taking it for the substance of God) is not divided. The

Scriptures by the Spirit of God in man, mean a mans spirit, enclined to Godlinesse. And where

it is said Exod. 28. 3. Whom I have filled with the spirit of wisdome to make garments for Aaron, is not meant a spirit put into them, that can make garments; but the wisdome of their own spirits in that kind of work. In the like sense, the spirit of man, when it produceth unclean

actions, is ordinarily called an unclean spirit; and so other spirits, though not alwayes, yet as

often as the vertue or vice so stiled, is extraordinary, and Eminent. Neither did the other

Prophets of the old Testament pretend Enthusiasme; or, that God spake in them; but to them

by Voyce, Vision, or Dream; and the Burthen of the Lord was not Possession, but Command.

How then could the Jewes fall into this opinion of possession? I can imagine no reason, but

that which is common to all men; namely, the want of curiosity to search naturall causes; and

their placing Felicity, in the acquisition of the grosse pleasures of the Senses, and the things

that most immediately conduce thereto. For they that see any strange, and unusuall ability, or

defect in a mans mind; unlesse they see withall, from what cause it may probably proceed, can

hardly think it naturall; and if not naturall, they must needs thinke it supernaturall; and then

what can it be, but that either God, or the Divell is in him? And hence it came to passe, when

our Saviour ( Mark 3. 21.) was compassed about with the multitude, those of the house

doubted he was mad, and went out to hold him: but the Scribes said he had Belzebub, and

that was it, by which he cast out divels; as if the greater mad-man had awed the lesser. And

that ( John 10. 20.) some said, He hath a Divell, and is mad; whereas others holding him for a Prophet, sayd, These are not the words of one that hath a Divell. So in the old Testament he that came to anoynt Jehu, 2 Kings 9. 11. was a Prophet; but some of the company asked Jehu, What came that mad-man for? So that in summe, it is manifest, that whosoever behaved

himselfe in extraordinory manner, was thought by the Jewes to be possessed either with a

good, or evill spirit; except by the Sadduces, who erred so farre on the other hand, as not to

believe there were at all any spirits, (which is very neere to direct Atheisme;) and thereby

perhaps the more provoked others, to terme such men Dæmoniacks, rather than mad-men.

But why then does our Saviour proceed in the curing of them, as if they were possest; and not

as if they were mad? To which I can give no other kind of answer, but that which is given to

those that urge the Scripture in like manner against the opinion of the motion of the Earth. The

Scripture was written to shew unto men the kingdome of God; and to prepare their mindes to

become his obedient subjects; leaving the world, and the Philosophy thereof, to the disputation

of men, for the exercising of their naturall Reason. Whether the Earths, or Suns motion make

the day, and night; or whether the Exorbitant actions of men, proceed from Passion, or from

the Divell, (so we worship him not) it is all one, as to our obedience, and subjection to God

Almighty; which is the thing for which the Scripture was written. As for that our Saviour

speaketh to the disease, as to a person; it is the usuall phrase of all that cure by words onely,

as Christ did, (and Inchanters pretend to do, whether they speak to a Divel or not.) For is not

Christ also said ( Math. 8. 26.) to have rebuked the winds? Is not he said also ( Luk. 4. 39.) to rebuke a Fever? Yet this does not argue that a Fever is a Divel. And whereas many of those

Divels are said to confesse Christ; it is not necessary to interpret those places otherwise, than

that those mad-men confessed him. And whereas our Saviour ( Math. 12. 43.) speaketh of an

unclean Spirit, that having gone out of a man, wandreth through dry places, seeking rest, and

finding none; and returning into the same man, with seven other spirits worse than himselfe;

It is manifestly a Parable, alluding to a man, that after a little endeavour to quit his lusts, is

vanquished by the strength of them; and becomes seven times worse than he was. So that I

see nothing at all in the Scripture, that requireth a beliefe, that Dæmoniacks were any other

thing but Mad-men.

Insignificant Speech.

There is yet another fault in the Discourses of some men; which may also be numbred

amongst the sorts of Madnesse; namely, that abuse of words, whereof I have spoken before in

the fifth chapter, by the Name of Absurdity. And that is, when men speak such words, as put

together, have in them no signification at all; but are fallen upon by some, through

misunderstanding of the words they have received, and repeat by rote; by others, from

intention to deceive by obscurity. And this is incident to none but those, that converse in

questions of matters incomprehensible, as the Schoole-men; or in questions of abstruse

Philosophy. The common sort of men seldome speak Insignificantly, and are therefore, by

those other Egregious persons counted Idiots. But to be assured their words are without any

thing correspondent to them in the mind, there would need some Examples; which if any man

require, let him take a Schoole-man into his hands, and see if he can translate any one chapter

concerning any difficult point; as the Trinity; the Deity; the nature of Christ; Transub-

stantiation; Free-will, &c. into any of the moderne tongues, so as to make the same

intelligible; or into any tolerable Latine, such as they were acquainted withall, that lived when

the Latine tongue was Vulgar. What is the meaning of these words. The first cause does not

necessarily inflow any thing into the second, by force of the Essentiall subordination of the

second causes, by Which it may help it to worke? They are the Translation of the Title of the sixth chapter of Suarez first Booke, Of the Concourse, Motion, and Help of God. When men write whole volumes of such stuffe, are they not Mad, or intend to make others so? And

particularly, in the question of Transubstantiation; where after certain words spoken, they that

say, the White nesse, Round nesse, Magni tude, Quali ty, Corruptibili ty, all which are incorporeall,

&c. go out of the Wafer, into the Body of our blessed Saviour, do they not make those Nesses, Tudes, and Ties, to be so many spirits possessing his body? For by Spirits, they mean alwayes things, that being incorporeall, are neverthelesse moveable from one place to another. So that

this kind of Absurdity, may rightly be numbred amongst the many sorts of Madnesse; and all

the time that guided by clear Thoughts of their worldly lust, they forbear disputing, or writing

thus, but Lucide Intervals And thus much of the Vertues and Defects Intellectuall.

CHAP. IX.

Of the Severall SUBJECTS of KNOWLEDGE.

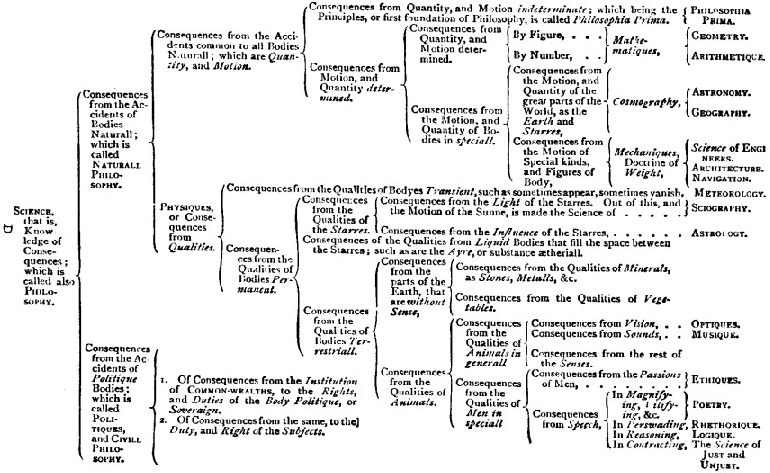

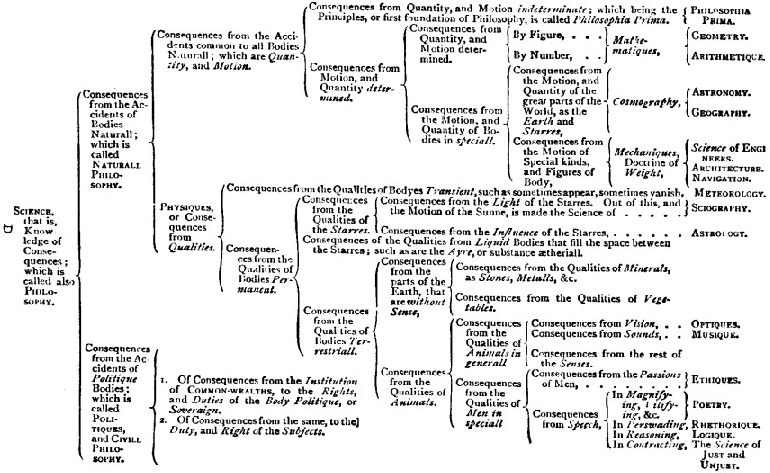

THERE are of KNOWLEDGE two kinds; whereof one is Knowledge of Fact: the other Knowledge

of the Consequence of one Affirmation to another. The former is nothing else, but Sense and

Memory, and is Absolute Knowledge; as when we see a Fact doing, or remember it done: And

this is the Knowledge required in a Witnesse. The later is called Science; and is Conditionall; as when we know, that, If the figure showne be a Circle, then any straight line through the Center

shall divide it into two equall parts. And this is the Knowledge required in a Philosopher; that is to say, of him that pretends to Reasoning.

The Register of Knowledge of Fact is called History. Whereof there be two sorts: one called Naturall History; which is the History of such Facts, or Effects of Nature, as have no

Dependance on Mans Will; Such as are the Histories of Metalls, Plants, Animals, Regions, and the like. The other, is Civill History; which is the History of the Voluntary Actions of men in Common-wealths.

The Registers of Science, are such Books as contain the Demonstrations of Consequences of one Affirmation, to another; and are commonly called Books of Philosophy; whereof the sorts

are many, according to the diversity of the Matter; And may be divided in such manner as I

have divided them in the following Table.

CHAP. X.

Of POWER, WORTH, DIGNITY, HONOUR, and WORTHINESSE.

Power.

THE POWER of a Man, (to take it Universally,) is his present means, to obtain some future

apparent Good. And is either Originall, or Instrumentall.

Naturall Power, is the eminence of the Faculties of Body, or Mind: as extraordinary Strength, Forme, Prudence, Arts, Eloquence, Liberality, Nobility. Instrumentall are those Powers, which acquired by these, or by fortune, are means and Instruments to acquire more: as Riches,

Reputation, Friends, and the secret working of God, which men call Good Luck. For the nature

of Power, is in this point, like to Fame, increasing as it proceeds; or like the motion of heavy

bodies, which the further they go, make still the more hast.

The Greatest of humane Powers, is that which is compounded of the Powers of most men,

united by consent, in one person, Naturall, or Civill, that has the use of all their Powers

depending on his will; such as is the Power of a Common-wealth: Or depending on the wills of

each particular; such as is the Power of a Faction, or of divers factions leagued. Therefore to

have servants, is Power; To have friends, is Power: for they are strengths united.

Also Riches joyned with liberality, is Power; because it procureth friends, and servants:

Without liberality, not so; because in this case they defend not; but expose men to Envy, as a

Prey.

Reputation of power, is Power; because it draweth with it the adhærence of those that need

protection.

So is Reputation of love of a mans Country, (called Popularity,) for the same Reason.

Also, what quality soever maketh a man beloved, or feared of many; or the reputation of such

quality, is Power; because it is a means to have the assistance, and service of many.

Good successe is Power; because it maketh reputation of Wisdome, or good fortune; which

makes men either feare him, or rely on him.

Affability of men already in power, is encrease of Power; because it gaineth love.

Reputation of Prudence in the conduct of Peace or War, is Power; because to prudent men, we

commit the government of our selves, more willingly than to others.

Nobility is Power, not in all places, but onely in those Common-wealths, where it has

Priviledges: for in such priviledges consisteth their Power.

Eloquence is power; because it is seeming Prudence.

Forme is Power; because being a promise of Good. it recommendeth men to the favour of

women and strangers.

The Sciences, are small Power; because not eminent; and therefore, not acknowledged in any

man; nor are at all, but in a few; and in them, but of a few things. For Science is of that

nature, as none can understand it to be, but such as in a good measure have attayned it.

Arts of publique use, as Fortification, making of Engines, and other Instruments of War;

because they conferre to Defence, and Victory, are Power: And though the true Mother of

them, be Science, namely the Mathematiques; yet, because they are brought into the Light, by

the hand of the Artificer, they be esteemed (the Midwife passing with the vulgar for the

Mother,) as his issue.

Worth.

The Value, or WORTH of a man, is as of all other things, his Price; that is to say, so much as would be given for the use of his Power: and therefore is not absolute; but a thing dependant

on the need and judgement of another. An able conductor of Souldiers, is of great Price in time

of War present, or imminent; but in Peace not so. A learned and uncorrupt Judge, is much

Worth in time of Peace; but not so much in War. And as in other things, so in men, not the

seller, but the buyer determines the Price. For let a man (as most men do,) rate themselves at

the highest Value they can; yet their true Value is no more than it is esteemed by others.

The manifestation of the Value we set on one another, is that which is commonly called

Honouring, and Dishonouring. To Value a man at a high rate, is to Honour him; at a low rate, is to Dishonour him. But high, and low, in this case, is to be understood by comparison to the rate that each man setteth on himselfe.

Dignity.

The publique worth of a man, which is the Value set on him by the Common-wealth, is that

which men commonly call DIGNITY. And this Value of him by the Common-wealth, is

understood, by offices of Command, Judicature, publike Employment; or by Names and Titles,

introduced for distinction of such Value.

To Honour and Dishonour.

To pray to another, for ayde of any kind, is to HONOUR; because a signe we have an opinion

he has power to help; and the more difficult the ayde is, the more is the Honour.

To obey, is to Honour; because no man obeyes them, whom they think have no power to help,

or hurt them. And consequently to disobey, is to Dishonour.

To give great gifts to a man, is to Honour him; because 'tis buying of Protection, and

acknowledging of Power. To give little gifts, is to Dishonour; because it is but Almes, and

signifies an opinion of the need of small helps.

To be sedulous in promoting anothers good; also to flatter, is to Honour; as a signe we seek

his protection or ayde. To neglect, is to Dishonour.

To give way, or place to another, in any Commodity, is to Honour; being a confession of

greater power. To arrogate, is to Dishonour.

To shew any signe of love, or feare of another, is to Honour; for both to love, and to feare, is to

value. To contemne, or lesse to love or feare, then he expects, is to Dishonour; for 'tis

undervaluing.

To praise, magnifie, or call happy, is to Honour; because nothing but goodnesse, power, and

felicity is valued. To revile, mock, or pitty, is to Dishonour.

To speak to another with consideration, to appear before him with decency, and humility, is to

Honour him; as signes of fear to offend. To speak to him rashly, to do any thing before him

obscenely, slovenly, impudently, is to Dishonour.

To believe, to trust, to rely on another, is to Honour him; signe of opinion of his vertue and

power. To distrust, or not believe, is to Dishonour.

To hearken to a mans counsell, or discourse of what kind soever, is to Honour; as a signe we

think him wise, or eloquent, or witty. To sleep, or go forth, or talk the while, is to Dishonour.

To do those things to another, which he takes for signes of Honour, or which the Law or

Custome makes so, is to Honour; because in approving the Honour done by others, he

acknowledgeth the power which others acknowledge. To refuse to do them, is to Dishonour.

To agree with in opinion, is to Honour; as being a signe of approving his judgement, and

wisdome. To dissent, is Dishonour; and an upbraiding of errour; and (if the dissent be in many

things) of folly.

To imitate, is to Honour; for it is vehemently to approve. To imitate ones Enemy, is to

Dishonour.

To honour those another honours, is to Honour him; as a signe of approbation of his

judgement. To honour his Enemies, is to Dishonour him.

To employ in counsell, or in actions of difficulty, is to Honour; as a signe of opinion of his

wisdome, or other power. To deny employment in the same cases, to those that seek it, is to

Dishonour.

All these wayes of Honouring, are naturall; and as well within, as without Common-wealths.

But in Common-wealths, where he, or they that have the supreme Authority, can make

whatsoever they please, to stand for signes of Honour, there be other Honours.

A Soveraigne doth Honour a Subject, with whatsoever Title, or Office, or Employment, or

Action, that he himselfe will have taken for a signe of his will to Honour him.

The King of Persia, Honoured Mordecay, when he appointed he should be conducted through the streets in the Kings Garment, upon one of the Kings Horses, with a Crown on his head, and

a Prince before him, proclayming, Thus shall it be done to him that the King will honour. And yet another King of Persia, or the same another time, to one that demanded for some great

service, to weare one of the Kings robes, gave him leave so to do; but with this addition, that

he should weare it as the Kings foole; and then it was Dishonour. So that of Civil Honour, the

Fountain is in the person of the Common-wealth, and dependeth on the Will of the Soveraigne;

and is therefore temporary, and called Civill Honour; such as are Magistracy, Offices, Titles; and in some places Coats, and Scutchions painted: and men Honour such as have them, as

having so many signes of favour in the Common-wealth; which favour is Power.

Honourable.

Honourable is whatsoever possession, action, or quality, is an argument and signe of Power.

And therefore To be Honoured, loved, or feared of many, is Honourable; as arguments of

Power. To be Honoured of few or none, Dishonourable.

Dishonourable.

Dominion, and Victory is Honourable; because acquired by Power; and Servitude, for need, or

feare, is Dishonourable.

Good fortune (if lasting,) Honourable; as a signe of the favour of God. Ill fortune, and losses,

Dishonourable. Riches, are Honourable; for they are Power. Poverty, Dishonourable.

Magnanimity, Liberality, Hope, Courage, Confidence, are Honourable; for they proceed from

the conscience of Power. Pusillanimity, Parsimony, Fear, Diffidence, are Dishonourable.

Timely Resolution, or determination of what a man is to do, is Honourable; as being the

contempt of small difficulties, and dangers. And Irresolution, Dishonourable; as a signe of too

much valuing of little impediments, and little advantages: For when a man has weighed things

as long as the time permits, and resolves not, the difference of weight is but little; and

therefore if he resolve not, he overvalues little things, which is Pusillanimity.

All Actions, and Speeches, that proceed, or seem to proceed from much Experience, Science,

Discretion, or Wit, are Honourable; For all these are Powers. Actions, or Words that proceed

from Errour, Ignorance, or Folly, Dishonourable.

Gravity, as farre forth as it seems to proceed from a mind employed on some thing else, is

Honourable; because employment is a signe of Power. But if it seem to proceed from a purpose

to appear grave, it is Dishonourable. For the gravity of the former, is like the steddinesse of a

Ship laden with Merchandise; but of the later, like the steddinesse of a Ship ballasted with

Sand, and other trash.

To be Conspicuous, that is to say, to be known, for Wealth, Office, great Actions, or any

eminent Good, is Honourable; as a signe of the power for which he is conspicuous. On the

contrary, Obscurity, is Dishonourable.

To be descended from conspicuous Parents, is Honourable; because they the more easily attain

the aydes, and friends of their Ancestors. On the contrary, to be descended from obscure

Parentage, is Dishonourable.

Actions proceeding from Equity, joyned with losse, are Honourable; as signes of Magnanimity:

for Magnanimity is a signe of Power. On the contrary, Craft, Shifting, neglect of Equity, is

Dishonourable.

Covetousnesse of great Riches, and ambition of great Honours, are Honourable; as signes of

power to obtain them. Covetousnesse, and ambition, of little gaines, or preferments, is

Dishonourable.

Nor does it alter the case of Honour, whether an action (so it be great and difficult, and