• Lightning

• Extremely high winds

• Avalanches

• Increased frequency and dura-

Fog

• Reduced mobility/visibility

tion

• Greatly decreased visibility at

Cloudiness

• Reduced visibility

higher elevations

Figure 1-4. Comparison of Weather Effects

WIND

1-22. In high mountains, the ridges and passes are seldom calm. By contrast, strong winds in protected valleys are rare. Normally, wind velocity increases with altitude and is intensified by mountainous terrain. Valley breezes moving up-slope are more common in the morning, while descending mountain breezes are more common in the evening. Wind speed increases when winds are forced over ridges and peaks (orographic lifting), or when they funnel through narrowing mountain valleys, passes, and canyons (Venturi effect).

Wind may blow with great force on an exposed mountainside or summit. As wind speed doubles, its force on an object nearly quadruples.

1-23. Mountain winds cause rapid temperature changes and may result in blowing snow, sand, or debris that can impair movement and observation.

Commanders should routinely consider the combined cooling effect of ambient temperature and wind (windchill) experienced by their soldiers (see Figure 1-5 on page 1-8). At higher elevations, air is considerably dryer than air at sea level. Due to this increased dryness, soldiers must increase their fluid 1-7

FM 3-97.6 ________________________________________________________________________________

intake by approximately one-third. However, equipment will not rust as quickly, and organic matter will decompose more slowly.

WIND SPEED

COOLING POWER OF WIND EXPRESSED AS “EQUIVALENT CHILL TEMPERATURE”

KNOTS

MPH

TEMPERATURE (o F)

CALM

CALM

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

-0

-5

-10

-15

-20

-25

-30

-35

-40

-45

-50

-55

-60

EQUIVALENT CHILL TEMPERATURE

3-6

5

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

-5

-10

-15

-20

-25

-30

-35

-40

-45

-50

-55

-60

-70

7-10

10

30

20

15

10

5

0

-10

-15

-20

-25

-35

-40

-45

-50

-60

-65

-70

-75

-80

-90

-95

11-15

15

25

15

10

0

-5

-10

-20

-25

-30

-40

-45

-50

-60

-65

-70

-80

-85

-90

-100

-105

-110

16-19

20

20

10

5

0

-10

-15

-25

-30

-35

-45

-50

-60

-65

-75

-80

-85

-95

-100

-110

-115

-120

20-23

25

15

10

0

-5

-15

-20

-30

-35

-45

-50

-60

-65

-75

-80

-90

-95

-105

-110

-120

-125

-135

24-28

30

10

5

0

-10

-20

-25

-30

-40

-50

-55

-65

-70

-80

-85

-95

-100

-110

-115

-125

-130

-140

29-32

35

10

5

-5

-10

-20

-30

-35

-40

-50

-60

-65

-75

-80

-90

-100

-105

-115

-120

-130

-135

-145

33-36

40

10

0

-5

-15

-20

-30

-35

-45

-55

-60

-70

-75

-85

-95

-100

-110

-115

-125

-130

-140

-150

WINDS ABOVE

40 HAVE

LITTLE DANGER

INCREASING DANGER

GREAT DANGER

LITTLE

(Flesh may freeze within 1 minute)

(Flesh may freeze within 30 secs)

ADDITIONAL

EFFECT

Figure 1-5. Windchill Chart

PRECIPITATION

1-24. The rapid rise of air masses over mountains creates distinct local weather patterns. Precipitation in mountains increases with elevation and occurs more often on the windward than on the leeward side of ranges.

Maximum cloudiness and precipitation generally occur near 1,800 meters (6,000 feet) elevation in the middle latitudes and at lower levels in the higher latitudes. Usually, a heavily wooded belt marks the zone of maximum precipitation.

Rain and Snow

1-25. Both rain and snow are common in mountainous regions. Rain presents the same challenges as at lower elevations, but snow has a more significant influence on all operations. Depending on the specific region, snow may occur at anytime during the year at elevations above 1,500 meters (5,000 feet).

Heavy snowfall greatly increases avalanche hazards and can force changes to previously selected movement routes. In certain regions, the intensity of snowfall may delay major operations for several months. Dry, flat riverbeds may initially seem to be excellent locations for assembly areas and support activities, however, heavy rains and rapidly thawing snow and ice may create flash floods many miles downstream from the actual location of the rain or snow.

1-8

_______________________________________________________________________________ Chapter 1

Thunderstorms

1-26. Although thunderstorms are local and usually last only a short time, they can impede mountain operations. Interior ranges with continental climates are more conducive to thunderstorms than coastal ranges with maritime climates. In alpine zones, driving snow and sudden wind squalls often accompany thunderstorms. Ridges and peaks become focal points for lightning strikes, and the occurrence of lightning is greater in the summer than the winter. Although statistics do not show lightning to be a major mountaineering hazard, it should not be ignored and soldiers should take normal precautions, such as avoiding summits and ridges, water, and contact with metal objects.

Traveling Storms

1-27. Storms resulting from widespread atmospheric disturbances involve strong winds and heavy precipitation and are the most severe weather condition that occurs in the mountains. If soldiers encounter a traveling storm in alpine zones during winter, they should expect low temperatures, high winds, and blinding snow. These conditions may last several days longer than in the lowlands. Specific conditions vary depending on the path of the storm. However, when colder weather moves in, clearing at high elevations is usually slow.

Fog

1-28. The effects of fog in mountains are much the same as in other terrain.

However, because of the topography, fog occurs more frequently in the mountains. The high incidence of fog makes it a significant planning consideration as it restricts visibility and observation complicating reconnaissance and surveillance. However, fog may help facilitate covert operations such as infiltration. Routes in areas with a high occurrence of fog may need to be marked and charted to facilitate passage.

SECTION II – EFFECTS ON PERSONNEL

1-29. The mountain environment is complex and unforgiving of errors. Soldiers conducting operations anywhere, even under the best conditions, become cold, thirsty, tired, and energy-depleted. In the mountains however, they may become paralyzed by cold and thirst and incapacitated due to utter exhaustion. Conditions such as high elevations, rough terrain, and extremely unpredictable weather require leaders and soldiers who have a keen understanding of environmental threats and what to do about them.

1-30. A variety of individual soldier characteristics and environmental conditions influence the type, prevalence, and severity of mountain illnesses and injuries (see Figure 1-6 on page 1-10). Due to combinations of these characteristics and conditions, soldiers often succumb to more than one illness or injury at a time, increasing the danger to life and limb. Three of the most common, cumulative, and subtle factors affecting soldier ability under these variable conditions are nutrition (to include water intake), decreased oxygen due to high altitude, and cold. Preventive measures, early recognition, and 1-9

FM 3-97.6 ________________________________________________________________________________

rapid treatment help

minimize nonbattle

PRECIPITATION

casualties due to these

conditions (see Appen-

TEMPERATURE

dix A for detailed in-

ELEVATION

formation on moun-

tain-specific illnesses

AGE

and injuries).

FATIGUE

WIND

NUTRITION AND ACTIVITY

NUTRITION

VELOCITY

RACE AND AREA OF ORIGIN

TRAINING AND EXPERIENCE

1-31. Poor nutrition

PREVIOUS/EXISTING INJURIES

contributes to illness

USE OF MEDICATIONS

or injury, decreased

MEDICAL HISTORY

performance, poor mo-

rale, and susceptibility

to cold injuries, and

can severely affect

Figure 1-6. Environmental and Soldier Conditions

military operations.

Influencing Mountain Injuries and Illnesses

Influences at high alti-

tudes that can affect nutrition include a dulled taste sensation (making food undesirable), nausea, and lack of energy or motivation to prepare or eat meals.

1-32. Caloric requirements increase in the mountains due to both the altitude and the cold. A diet high in fat and carbohydrates is important in helping the body fight the effects of these conditions. Fats provide long-term, slow caloric release, but are often unpalatable to soldiers operating at higher altitudes.

Snacking on high-carbohydrate foods is often the best way to maintain the calories necessary to function.

1-33. Products that can seriously impact soldier performance in mountain operations include:

• Tobacco. Tobacco smoke interferes with oxygen delivery by reducing the blood’s oxygen-carrying capacity. Tobacco smoke in close, confined spaces increases the amounts of carbon monoxide. The irritant effect of tobacco smoke may produce a narrowing of airways, interfering with optimal air movement. Smoking can effectively raise the “physiological altitude” as much as several hundred meters.

• Alcohol. Alcohol impairs judgement and perception, depresses respiration, causes dehydration, and increases susceptibility to cold injury.

• Caffeine. Caffeine may improve physical and mental performance, but it also causes increased urination (leading to dehydration) and, therefore, should be consumed in moderation.

1-34. Significant body water is lost at higher elevations from rapid breathing, perspiration, and urination. Depending upon level of exertion, each soldier should consume about four to eight quarts of water or other decaffeinated fluids per day in low mountains and may need ten quarts or more per day in high mountains. Thirst is not a good indicator of the amount of water lost, 1-10

_______________________________________________________________________________ Chapter 1

and in cold climates sweat, normally an indicator of loss of fluid, goes unno-ticed. Sweat evaporates so rapidly or is absorbed so thoroughly by clothing layers that it is not readily apparent. When soldiers become thirsty, they are already dehydrated. Loss of body water also plays a major role in causing altitude sickness and cold injury. Forced drinking in the absence of thirst, monitoring the deepness of the yellow hue in the urine, and watching for behavioral symptoms common to altitude sickness are important factors for commanders to consider in assessing the water balance of soldiers operating in the mountains.

1-35. In the mountains, as elsewhere, refilling each soldier's water containers as often as possible is mandatory. No matter how pure and clean mountain water may appear, water from natural sources should always be purified or chemically sterilized to prevent parasitical illnesses (giardiasis). Commanders should consider requiring the increased use of individual packages of powdered drink mixes, fruit, and juices to help encourage the required fluid intake.

ALTITUDE

1-36. As soldiers ascend in altitude, the proportion of oxygen in the air decreases. Without proper acclimatization, this decrease in oxygen saturation can cause altitude sickness and reduced physical and mental performance (see Figure 1-7). Soldiers cannot maintain the same physical performance at high altitude that they can at low altitude, regardless of their fitness level.

Altitude

Meters

Feet

Effects

Low

Sea Level – 1,500

Sea Level – 5,000

None.

Mild, temporary altitude sick-

Moderate

1,500 – 2,400

5,000 – 8,000

ness may occur

Altitude sickness and de-

High

2,400 – 4,200

8,000 – 14,000

creased performance is in-

creasingly common

Altitude sickness and de-

Very High

4,200 – 5,400

14,000 – 18,000

creased performance is the

rule

With acclimatization, soldiers

Extreme

5,400 – Higher

18,000 - Higher

can function for short periods

of time

Figure 1-7. Effects of Altitude

1-37. The mental effects most noticeable at high altitudes include decreased perception, memory, judgement, and attention. Exposure to altitudes of over 3,000 meters (10,000 feet) may also result in changes in senses, mood, and personality. Within hours of ascent, many soldiers may experience euphoria, joy, and excitement that are likely to be accompanied by errors in judgement, leading to mistakes and accidents. After a period of about 6 to 12 hours, euphoria decreases, often changing to varying degrees of depression. Soldiers may become irritable or may appear listless. Using the buddy system during this early exposure helps to identify soldiers who may be more severely affected. High morale and esprit instilled before deployment and reinforced frequently help to minimize the impact of negative mood changes.

1-11

FM 3-97.6 ________________________________________________________________________________

1-38. The physical effect most noticeable at high altitudes includes vision. Vision is generally the sense most affected by altitude exposure and can potentially affect military operations at higher elevations. Night vision is significantly reduced, affecting soldiers at approximately 2,400 meters (8,000 feet) or higher. Some effects occur early and are temporary, while others may persist after acclimatization or even for a period of time after descent. To compensate for loss of functional abilities, commanders should make use of tactics, techniques, and procedures that trade speed for increased accuracy. By allowing extra time to accomplish tasks, commanders can minimize errors and injuries.

HYPOXIA-RELATED ILLNESSES AND EFFECTS

1-39. Hypoxia, a deficiency of oxygen reaching the tissues of the body, has been the cause of many mountain illnesses, injuries, and deaths. It affects everyone, but some soldiers are more vulnerable than others. A soldier may be affected at one time but not at another. Altitude hypoxia is a killer, but it seldom strikes alone. The combination of improper nutrition, hypoxia, and cold is much more dangerous than any of them alone. The three most significant altitude-related illnesses and their symptoms, which are essentially a series of illnesses associated with oxygen deprivation, are:

• Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS). Headache, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, irritability, and dizziness.

• High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE). Coughing, noisy breathing, wheezing, gurgling in the airway, difficulty breathing, and pink frothy sputum (saliva). Ultimately coma and death will occur without treatment.

• High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE). HACE is the most severe illness associated with high altitudes. Its symptoms often resemble AMS

(severe headache, nausea, vomiting), often with more dramatic signals such as a swaying of the upper body, especially when walking, and an increasingly deteriorating mental status. Early mental symptoms may include confusion, disorientation, vivid hallucinations, and drowsiness.

Soldiers may appear to be withdrawn or demonstrate behavior gener-

ally associated with fatigue or anxiety. Like HAPE, coma or death will occur without treatment.

OTHER MOUNTAIN-RELATED ILLNESSES

1-40. Other illnesses and effects related to the mountain environment and higher elevations are:

• Subacute mountain sickness. Subacute mountain sickness occurs in some soldiers during prolonged deployments (weeks/months) to elevations above 3,600 meters (12,000 feet). Symptoms include sleep disturbance, loss of appetite, weight loss, and fatigue. This condition reflects a failure to acclimatize adequately.

• Carbon monoxide poisoning. Carbon monoxide poisoning is caused by the inefficient fuel combustion resulting from the low oxygen content of air and higher usage of stoves, combustion heaters, and engines in en-closed, poorly ventilated spaces.

1-12

_______________________________________________________________________________ Chapter 1

• Sleep disturbances. High altitude has significant harmful effects on sleep. The most prominent effects are frequent periods of apnea (temporary suspension of respiration) and fragmented sleep. Sleep disturbances may last for weeks at elevations less than 5,400 meters (18,000

feet) and may never stop at higher elevations. These effects have even been reported as low as 1,500 meters (5,000 feet).

• Poor wound healing. Poor wound healing resulting from lowered im-mune functions may occur at higher elevations. Injuries resulting from burns, cuts, or other sources may require descent for effective treatment and healing.

ACCLIMATIZATION

1-41. Altitude acclimatization involves physiological changes that permit the body to adapt to the effects of low oxygen saturation in the air. It allows soldiers to achieve the maximum physical work performance possible for the altitude to which they are acclimatized. Once acquired, acclimatization is maintained as long as the soldier remains at that altitude, but is lost upon returning to lower elevations. Acclimatization to one altitude does not prevent altitude illnesses from occurring if ascent to higher altitudes is too rapid.

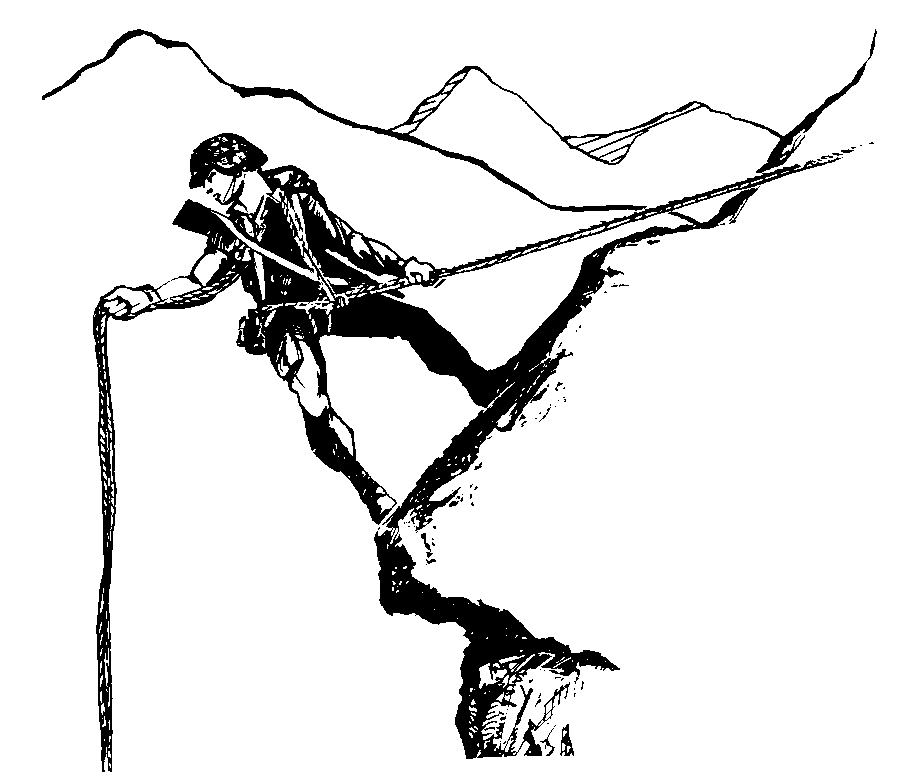

1-42. Getting used to living and working at

higher altitudes requires acclimatization.

• Altitude

Figure 1-8 shows the four factors that affect

•