What You Need

To Know About™

Prostate

Cancer

National Cancer Institute

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF

HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

National Institutes of Health

National Cancer Institute Services

This booklet is only one of many free

publications for people with cancer.

You may want more information for yourself,

your family, and your friends.

Call NCI’s Cancer Information Service

1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237)

Visit NCI’s website

http://www.cancer.gov

Chat online

LiveHelp, NCI’s instant messaging service

https://livehelp.cancer.gov

E-mail

cancergovstaff@mail.nih.gov

Order publications

http://www.cancer.gov/publications

1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237)

Get help with quitting smoking

1-877-44U-QUIT (1-877-448-7848)

About This Booklet

This National Cancer Institute (NCI) booklet is for you—a man who has just been diagnosed with prostate cancer. In 2012, about 242,000 American men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer.

Words that may be new to you are shown in bold. See the Words to Know section on page 32 to learn what a new word means and how to pronounce it.

This booklet tel s about medical care for men with prostate cancer. Learning about medical care for prostate cancer can help you take an active part in making choices about your care.

You can read this booklet from front to back. Or, you can read only the sections you need right now.

This booklet has lists of questions that you may want to ask your doctor. Many people find it helpful to take a list of questions to a doctor visit. To help remember what your doctor says, you can take notes. You may also want to have a family member or friend go with you when you talk with the doctor—to take notes, ask questions, or just listen.

Contents

1

The Prostate

1

Cancer Cells

4

Tests

7

Stages

9

Treatment

26

Nutrition

27

Follow-up Care

29 Sources of Support

30

Cancer Treatment Research

32 Words To Know

The Prostate

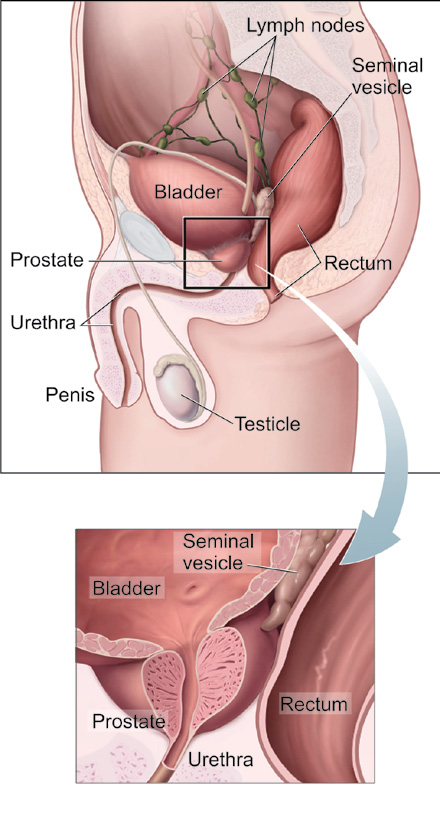

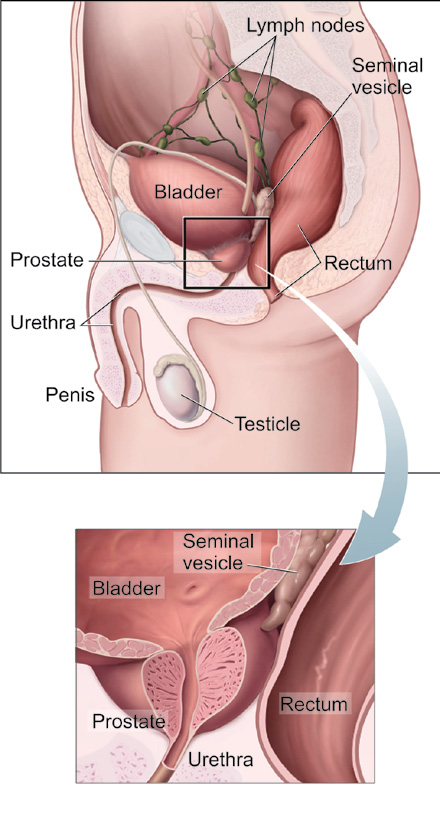

The prostate is part of a man’s reproductive system. It’s located in front of the rectum and under the bladder. (See picture on page 2.) The prostate surrounds the urethra, the tube through which urine flows.

A healthy prostate is about the size of a walnut. If the prostate grows too large, it squeezes the urethra. This may slow or stop the normal flow of urine.

The prostate is a gland. It makes part of the seminal fluid.

During orgasm, the seminal fluid helps carry sperm out of the man’s body as part of semen.

Cancer Cells

Cancer begins in cells, the building blocks that make up all tissues and organs of the body, including the prostate.

Normal cel s in the prostate and other parts of the body grow and divide to form new cel s as they are needed. When normal cel s grow old or get damaged, they die, and new cel s take their place.

Sometimes, this process goes wrong. New cel s form when the body doesn’t need them, and old or damaged cel s don’t die as they should. The buildup of extra cel s often forms a mass of tissue called a growth or tumor.

1

The first picture shows the prostate and nearby organs.

The second picture shows how the prostate surrounds the urethra.

2

Growths in the prostate can be benign (not cancer) or malignant (cancer):

■■ Benign growths (such as benign prostatic hypertrophy):

• Are rarely a threat to life

• Don’t invade the tissues around them

• Don’t spread to other parts of the body

• Can be removed and usual y don’t grow back

■■ Malignant growths (prostate cancer):

• May sometimes be a threat to life

• Can invade nearby organs and tissues (such as the bladder or rectum)

• Can spread to other parts of the body

• Often can be removed but sometimes grow back

Prostate cancer cel s can spread by breaking away from a prostate tumor. They can travel through blood vessels or lymph vessels to reach other parts of the body. After spreading, cancer cel s may attach to other tissues and grow to form new tumors that may damage those tissues.

When prostate cancer spreads from its original place to another part of the body, the new tumor has the same kind of abnormal cel s and the same name as the primary (original) tumor. For example, if prostate cancer spreads to the bones, the cancer cel s in the bones are actual y prostate cancer cel s. The disease is metastatic prostate cancer, not bone cancer. For that reason, it’s treated as prostate cancer, not bone cancer.

3

Tests

After you learn that you have prostate cancer, you may need other tests to help with making decisions about treatment.

Tumor Grade Test with Prostate Tissue

The prostate tissue that was removed during your biopsy procedure can be used in lab tests. The pathologist studies prostate tissue samples under a microscope to determine the grade of the tumor. The grade tel s how different the tumor tissue is from normal prostate tissue.

Tumors with higher grades tend to grow faster than those with lower grades. They are also more likely to spread.

Doctors use tumor grade along with your age and other factors to suggest treatment options.

The most commonly used system for grading prostate cancer is the Gleason score. Gleason scores range from 2 to 10.

To come up with the Gleason score, the pathologist looks at the patterns of cel s in the prostate tissue samples. The most common pattern of cel s is given a grade of 1 (most like normal prostate tissue) to 5 (most abnormal). If there is a second most common pattern, the pathologist gives it a grade of 1 to 5 and then adds the grades for the two most common patterns together to make the Gleason score (3 +

4 = 7). If only one pattern is seen, the pathologist counts it twice (5 + 5 = 10).

A high Gleason score (such as 10) means a high-grade prostate tumor. High-grade tumors are more likely than low-grade tumors to grow quickly and spread.

4

For more about tumor grade, see the NCI fact sheet Tumor Grade.

Staging Tests

Staging tests can show the stage (extent) of prostate cancer, such as whether cancer cel s have spread to other parts of the body.

When prostate cancer spreads, cancer cel s are often found in nearby lymph nodes. If cancer has reached these lymph nodes, it may have also spread to other lymph nodes, the bones, or other organs.

Your doctor needs to learn the stage of the prostate cancer to help you make the best decision about treatment.

Staging tests may include…

■■ Physical exam (digital rectal exam): If the tumor in the prostate is large enough to be felt, your doctor may be able to examine it. With a gloved and lubricated finger, your doctor feels the prostate and surrounding tissues from the rectum. Hard or lumpy areas may suggest the presence of one or more tumors. Your doctor may also be able to tell whether it’s likely that the tumor has grown outside the prostate.

■■ Bone scan: A small amount of a radioactive substance will be injected into a blood vessel. The radioactive substance travels through your bloodstream and collects in the bones. A machine called a scanner makes pictures of your bones. Because higher amounts of the radioactive substance collect in areas where there is cancer, the pictures can show cancer that has spread to the bones.

5

■■ CT scan: An x-ray machine linked to a computer takes a series of detailed pictures of your lower abdomen or other parts of your body. You may receive contrast material by injection into a blood vessel in your arm or hand, or by enema. The contrast material makes it easier to see abnormal areas. The pictures from a CT scan can show cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes or other areas.

■■ MRI: A strong magnet linked to a computer is used to make detailed pictures of your lower abdomen. An MRI can show whether cancer has spread to lymph nodes or other areas. Sometimes contrast material is used to make abnormal areas show up more clearly on the picture.

Questions you may want to ask your doctor about tests

■■ May I have a copy of the report from the pathologist?

■■ What is the grade of the tumor?

■■ Has the cancer spread from the prostate? If so, to where?

6

Stages

Doctors describe the stages of prostate cancer using the Roman numerals I, II, III, and IV. A cancer that is Stage I is early-stage cancer, and a cancer that is Stage IV is advanced cancer that has spread to other parts of the body.

The stage of prostate cancer depends mainly on…

■■ Whether the tumor has invaded nearby tissue, such as the bladder or rectum

■■ Whether prostate cancer cells have spread to lymph nodes or other parts of the body, such as the bones

■■ Grade (Gleason score) of the prostate tumor

■■ PSA level

On NCI’s website at http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/

types/prostate, you can find pictures and more information about the stages of prostate cancer.

Stage I

The cancer is only in the prostate. It might be too small to feel during a digital rectal exam. If the Gleason score and PSA level are known, the Gleason score is 6 or less, and the PSA level is under 10.

Stage II

The tumor is more advanced or a higher grade than Stage I, but the tumor doesn’t extend beyond the prostate.

7

Stage III

The tumor extends beyond the prostate. The tumor may have invaded a seminal vesicle, but cancer cel s haven’t spread to lymph nodes. See page 2 for a picture of a seminal vesicle.

Stage IV

The tumor may have invaded the bladder, rectum, or nearby structures (beyond the seminal vesicles). It may have spread to lymph nodes, bones, or other parts of the body.

You and your doctor will develop a treatment plan.

8

Treatment

Men with prostate cancer have many treatment options.

Treatment options include…

■■ Active surveillance

■■ Surgery

■■ Radiation therapy

■■ Hormone therapy

■■ Chemotherapy

■■ Immunotherapy

You may receive more than one type of treatment.

The treatment that’s best for one man may not be best for another. The treatment that’s right for you depends mainly on…

■■ Your age

■■ Gleason score (grade) of the tumor

■■ Stage of prostate cancer

■■ Your symptoms

■■ Your general health

At any stage of disease, care is available to control pain and other symptoms, to relieve the side effects of treatment, and to ease emotional concerns. You can get information about coping on NCI’s website at http://www.cancer.gov/

cancertopics/coping.

9

Also, you can get information about coping from NCI’s Cancer Information Service at 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237). Or, chat using NCI’s instant messaging service,

LiveHelp (https://livehelp.cancer.gov).

Doctors Who Treat Prostate Cancer

Your health care team will include specialists. There are many ways to find doctors who treat prostate cancer:

■■ Your doctor may be able to refer you to specialists.

■■ You can ask a local or state medical society, or a nearby hospital or medical school for names of specialists.

■■ NCI’s Cancer Information Service can give you information about treatment centers near you. Call 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237). Or, chat using

LiveHelp (https://livehelp.cancer.gov), NCI’s instant messaging service.

■■ Other sources can be found in the NCI fact sheet How To Find a Doctor or Treatment Facility If You Have Cancer.

Your health care team may include the following specialists:

■■ Urologist: A urologist is a doctor who specializes in treating problems in the urinary tract or male sex organs.

This type of doctor can perform surgery (an operation).

■■ Urologic oncologist: A urologic oncologist is a doctor who specializes in treating cancers of the male and female urinary tract and the male sex organs. This type of doctor also can perform surgery.

■■ Medical oncologist: A medical oncologist is a doctor who specializes in treating cancer with drugs, such as chemotherapy, hormone therapy, or immunotherapy.

10

■■ Radiation oncologist: A radiation oncologist is a doctor who specializes in treating cancer with

radiation therapy.

Your health care team may also include an oncology nurse, a social worker, and a registered dietitian.

Your health care team can describe your treatment options, the expected results of each option, and the possible side effects. Because cancer treatments often damage healthy cel s and tissues, side effects are common. These side effects depend on many factors, including the type of treatment.

Side effects may not be the same for each man, and they may even change from one treatment session to the next.

Before treatment starts, ask your health care team about possible side effects and how treatment may change your normal activities. For example, you may want to discuss with your doctor the possible effects on sexual activity. The NCI booklet Treatment Choices for Men with Early-Stage Prostate Cancer can tell you more about treatments and their side effects.

You and your health care team can work together to develop a treatment plan that meets your medical and personal needs.

You may want to talk with your health care team about taking part in a research study (clinical trial) of new treatment methods. Research studies are an important option for men at any stage of prostate cancer. See the Cancer Treatment Research section on page 30.

11

Questions you may want to ask your doctor about treatment options

■■ What are my treatment options? Which do you

recommend for me? Why?

■■ What are the expected benefits of each kind of treatment?

■■ What are the risks and possible side effects of each treatment? How can the side effects be managed?

■■ What can I do to prepare for treatment?

■■ Will I need to stay in the hospital? If so, for how long?

■■ What is the treatment likely to cost? Will my insurance cover it?

■■ How will treatment affect my normal activities? Will it affect my sex life? Will I have urinary problems? Will I have bowel problems?

■■ Would a research study (clinical trial) be right for me?

Second Opinion

Before starting treatment, you might want a second opinion about your diagnosis and treatment options. You may even want to talk to several different doctors about all treatment options, their side effects, and the expected results. For example, you may want to talk to a urologist, radiation oncologist, and medical oncologist.

12

Some men worry that the doctor will be offended if they ask for a second opinion. Usual y the opposite is true.

Most doctors welcome a second opinion. And many health insurance companies will pay for a second opinion if you or your doctor requests it. Some insurance companies actual y require a second opinion.

If you get a second opinion, the second doctor may agree with your first doctor’s diagnosis and treatment recommendation. Or, the second doctor may suggest another approach. Either way, you have more information and perhaps a greater sense of control. You can feel more confident about the decisions you make, knowing that you’ve looked at all of your options.

It may take some time and effort to gather your medical records and see another doctor. In most cases, it’s not a problem to take several weeks to get a second opinion. The delay in starting treatment usual y will not make treatment less effective. To make sure, you should discuss this delay with your doctor.

Active Surveillance

Your doctor may suggest active surveil ance if you’re diagnosed with early-stage prostate cancer that seems to be growing slowly. Your doctor may also offer this option if you are older or have other health problems.

Active surveil ance is putting off treatment until test results show that your prostate cancer is growing or changing. If you and your doctor agree that active surveil ance is a good idea, your doctor will check you regularly (such as every 3

to 6 months, at first). You’ll get digital rectal exams and PSA tests. After about a year, your doctor may order another 13

prostate biopsy to check the Gleason score. Your doctor may suggest treatment if your Gleason score rises, your PSA level starts to increase, or you develop symptoms. Your doctor may suggest surgery, radiation therapy, or another type of treatment.

By choosing active surveil ance, you’re putting off the side effects of surgery, radiation therapy, or other treatments.

However, the risk for some men is that waiting to start treatment may reduce the chance to control cancer before it spreads. Having regular checkups reduces this risk.

For some men, it’s stressful to live with an untreated prostate cancer. If you choose active surveil ance but grow concerned later, you should discuss your feelings with your doctor. You can change your mind and have treatment at any time.

Questions you may want to ask your doctor about active surveillance

■■ Is it safe for me to put off treatment? Does it mean I will not live as long as if I started treatment right away?

■■ Can I change my mind later on?

■■ How often will I have checkups? Which tests will I need? Will I need a repeat biopsy?

■■ How will we know if the prostate cancer is getting worse?

■■ Between checkups, what problems should I tell you about?

14

Surgery

Surgery is an option for men with early-stage cancer that is found only in the prostate. It’s sometimes also an option for men with advanced prostate cancer to relieve symptoms.

There are several kinds of surgery to treat prostate cancer.

Usual y, the surgeon will remove the entire prostate and nearby lymph nodes. Your surgeon can describe each kind of surgery, compare the benefits and risks, and help you decide which kind might be best for you.

The entire prostate can be removed in several ways…

■■ Through a large cut in the abdomen: The surgeon removes the prostate through a long incision in the abdomen below the bel y button. This is called a radical retropubic prostatectomy. Because of the long incision, it’s also called an open prostatectomy.

■■ Through small cuts in the abdomen: The surgeon makes several small cuts in the abdomen, and surgery tools are inserted through the small cuts. A long, thin tube (a laparoscope) with a light and a camera on the end helps the surgeon see the prostate while removing it. This is called a laparoscopic prostatectomy.

■■ With a robot: The surgeon may use a robot to remove the prostate through small incisions in the abdomen.

The surgeon uses handles below a computer display to control the robot’s arms.

■■ Through a large cut between the scrotum and anus: The surgeon removes the prostate through an incision between the scrotum and anus. This is called a radical perineal prostatectomy. It’s a type of open prostatectomy that is rarely used anymore.

15

Other surgery options for treating prostate cancer or relieving its symptoms are…

■■ Freezing: For some men, cryosurgery is an option. The surgeon inserts a tool through a small cut between the scrotum and anus. The tool freezes and kil s prostate tissue.

■■ Heating: Doctors are testing high-intensity focused ultrasound therapy in men with prostate cancer. A probe is placed in the rectum. The probe gives off high-intensity ultrasound waves that heat up and kill the prostate tumor.

■■ TURP: A man with advanced prostate cancer may choose transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) to relieve symptoms. The surgeon inserts a long, thin scope through the urethra. A cutting tool at the end of the scope removes tissue from the inside of the prostate.

TURP may not remove all of the cancer, but it can remove tissue that blocks the flow of urine.

You may be uncomfortable for the first few days or weeks after surgery. However, medicine can help control the pain.

Before surgery, you should discuss the plan for pain relief with your doctor or nurse. After surgery, your doctor can adjust the plan if you need more pain relief.

The time it takes to heal after surgery is different for each man and depends on the type of surgery. You may be in the hospital for 1 to 3 days.

After surgery, a tube will be inserted into your penis. The tube allows urine to drain from your bladder while the urethra is healing from the surgery. You’ll have the tube for 5 to 14 days. Your nurse or doctor will show you how to care for it.

16

After surgery, some men may lose control of the flow of urine (urinary incontinence). Most men regain at least some bladder control after a few weeks. Your nurse or doctor can teach you an exercise to help you recover control of your bladder. For some men, however, incontinence may be permanent. Your health care team can show you ways to cope with this problem.

Surgery may also damage nerves near the prostate and cause erectile dysfunction. Sexual function usual y improves over several months, but for some men, this problem can be permanent. Talk with your doctor about medicine and other ways to help manage the sexual side effects of prostate cancer treatment.

If your prostate is removed, you’ll have dry orgasms, which means you’ll no longer release semen. If you wish to father children, you may consider sperm banking before surgery.

Questions you may want to ask your doctor

about surgery

■■ Do you suggest surgery for me? If so, what kind of surgery do you recommend for me? Why?

■■ How will I feel after surgery? How long will I be in the hospital?

■■ If I have