2

Global Health and Aging

Photo credits front cover, left to right (Dreamstime.com): Djembe; Sergey Galushko; Laurin Rinder; Indianeye; Magomed Magomedagaev; and Antonella865.

Contents

Preface 1

Overview

2

Humanity’s Aging 4

Living Longer 6

New Disease Patterns 9

Longer Lives and Disability 12

New Data on Aging and Health 16

Assessing the Cost of Aging and Health Care 18

Health and Work 20

Changing Role of the Family 22

Suggested Resources 25

4

Global Health and Aging

Preface

The world is facing a situation without precedent: We soon will have more older people than children and more people at extreme old age than ever before. As both the proportion of older people and the length of life increase throughout the world, key questions arise. Will population aging be accompanied by a longer period of good health, a sustained sense of well-being, and extended periods of social engagement and productivity, or will it be associated with more illness, disability, and dependency? How will aging affect health care and social costs? Are these futures inevitable, or can we act to establish a physical and social infrastructure that might foster better health and wellbeing in older age? How will population aging play out differently for low-income countries that will age faster than their counterparts have, but before they become industrialized and wealthy?

This brief report attempts to address some of these questions. Above all, it emphasizes the central role that health will play moving forward. A better understanding of the changing relationship between health with age is crucial if we are to create a future that takes full advantage of the powerful resource inherent in older populations. To do so, nations must develop appropriate data systems and research capacity to monitor and understand these patterns and relationships, specifically longitudinal studies that incorporate measures of health, economic status, family, and well-being. And research needs to be better coordinated if we are to discover the most cost-effective ways to maintain healthful life styles and everyday functioning in countries at different stages of economic development and with varying resources. Global efforts are required to understand and find cures or ways to prevent such age-related diseases as Alzheimer’s and frailty and to implement existing knowledge about the prevention and treatment of heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and cancer.

Managing population aging also requires building needed infrastructure and institutions as soon as possible. The longer we delay, the more costly and less effective the solutions are likely to be.

Population aging is a powerful and transforming demographic force. We are only just beginning to comprehend its impacts at the national and global levels. As we prepare for a new demographic reality, we hope this report raises awareness not only about the critical link between global health and aging, but also about the importance of rigorous and coordinated research to close gaps in our knowledge and the need for action based on evidence-based policies.

Richard

Suzman,

PhD

John Beard, MBBS, PhD

Director, Division of Behavioral and Social Research Dir ector, Department of Ageing and Life Course

National Institute on Aging

World Health Organization

National Institutes of Health

Preface

5

1

Overview

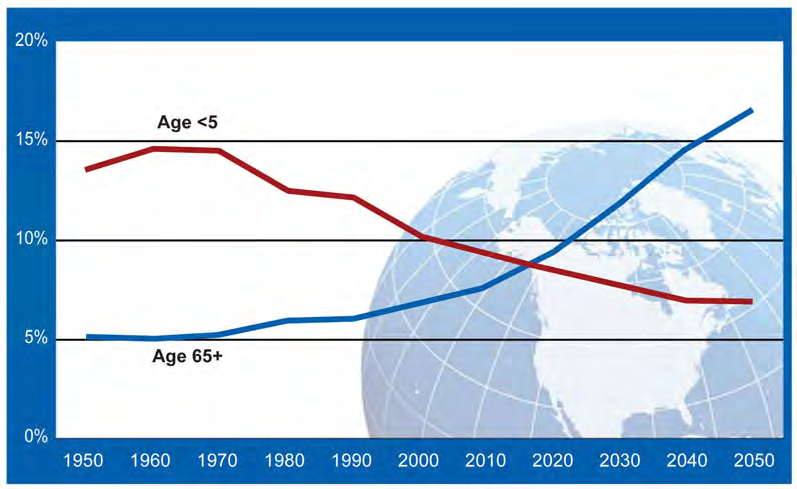

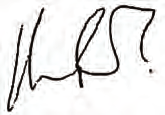

The world is on the brink of a demographic

the major health threats were infectious and

milestone. Since the beginning of recorded

parasitic diseases that most often claimed

history, young children have outnumbered

the lives of infants and children. Currently,

their elders. In about five years’ time, however,

noncommunicable diseases that more commonly

the number of people aged 65 or older will

affect adults and older people impose the

outnumber children under age 5. Driven by

greatest burden on global health.

falling fertility rates and remarkable increases in

life expectancy, population aging will continue,

In today’s developing countries, the rise of

even accelerate (Figure 1). The number of

chronic noncommunicable diseases such as

people aged 65 or older is projected to grow

heart disease, cancer, and diabetes reflects

from an estimated 524 million in 2010 to nearly

changes in lifestyle and diet, as well as aging.

1.5 billion in 2050, with most of the increase in

The potential economic and societal costs of

developing countries.

noncommunicable diseases of this type rise

sharply with age and have the ability to affect

The remarkable improvements in life

economic growth. A World Health Organization

expectancy over the past century were part

analysis in 23 low- and middle-income countries

of a shift in the leading causes of disease

estimated the economic losses from three

and death. At the dawn of the 20th century,

noncommunicable diseases (heart disease,

Figure 1.

Young Children and Older People as a Percentage of Global Population: 1950-2050

Source: United Nations. World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision.

Available at: http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp.

2

Global Health and Aging

stroke, and diabetes) in these countries would

With continuing declines in death rates among

total US$83 billion between 2006 and 2015.

older people, the proportion aged 80 or older

is rising quickly, and more people are living

Reducing severe disability from disease

past 100. The limits to life expectancy and

and health conditions is one key to holding

lifespan are not as obvious as once thought.

down health and social costs. The health

And there is mounting evidence from cross-

and economic burden of disability also can

national data that—with appropriate policies

be reinforced or alleviated by environmental

and programs—people can remain healthy

characteristics that can determine whether

and independent well into old age and can

an older person can remain independent

continue to contribute to their communities

despite physical limitations. The longer people

and families.

can remain mobile and care for themselves,

the lower are the costs for long-term care to

The potential for an active, healthy old age

families and society.

is tempered by one of the most daunting and

potentially costly consequences of ever-longer

Because many adult and older-age health

life expectancies: the increase in people with

problems were rooted in early life experiences

dementia, especially Alzheimer’s disease. Most

and living conditions, ensuring good child

dementia patients eventually need constant

health can yield benefits for older people.

care and help with the most basic activities

In the meantime, generations of children

of daily living, creating a heavy economic and

and young adults who grew up in poverty

social burden. Prevalence of dementia rises

and ill health in developing countries will be

sharply with age. An estimated 25-30 percent

entering old age in coming decades, potentially

of people aged 85 or older have dementia.

increasing the health burden of older

Unless new and more effective interventions

populations in those countries.

are found to treat or prevent Alzheimer’s

disease, prevalence is expected to rise

dramatically with the aging of the population

in the United States and worldwide.

Aging is taking place alongside other broad

social trends that will affect the lives of older

people. Economies are globalizing, people are

more likely to live in cities, and technology

is evolving rapidly. Demographic and family

changes mean there will be fewer older people

with families to care for them. People today

have fewer children, are less likely to be

married, and are less likely to live with older

generations. With declining support from

families, society will need better information

and tools to ensure the well-being of the

world’s growing number of older citizens.

Dundanim | Dreamstime.com

Overview

3

Humanity’s Aging

In 2010, an estimated 524 million people were

nearly three children per woman around 1950.

aged 65 or older—8 percent of the world’s

Even more crucial for population aging, fertility

population. By 2050, this number is expected to fell with surprising speed in many less developed nearly triple to about 1.5 billion, representing

countries from an average of six children in

16 percent of the world’s population. Although

1950 to an average of two or three children

more developed countries have the oldest

in 2005. In 2006, fertility was at or below the

population profiles, the vast majority of

two-child replacement level in 44 less developed

older people—and the most rapidly aging

countries.

populations—are in less developed countries.

Between 2010 and 2050, the number of older

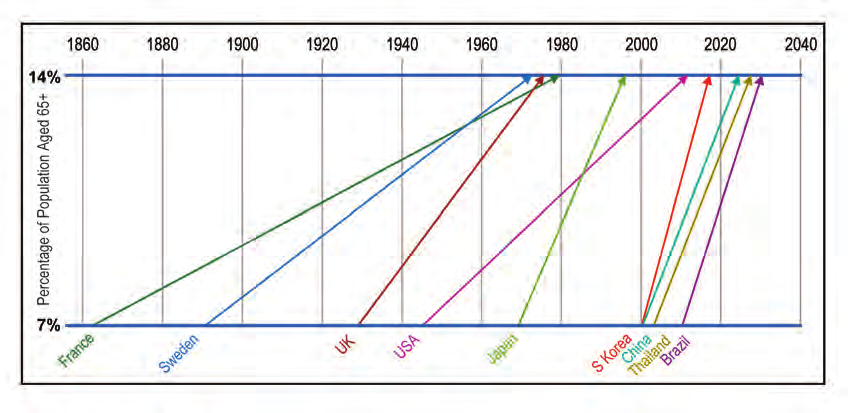

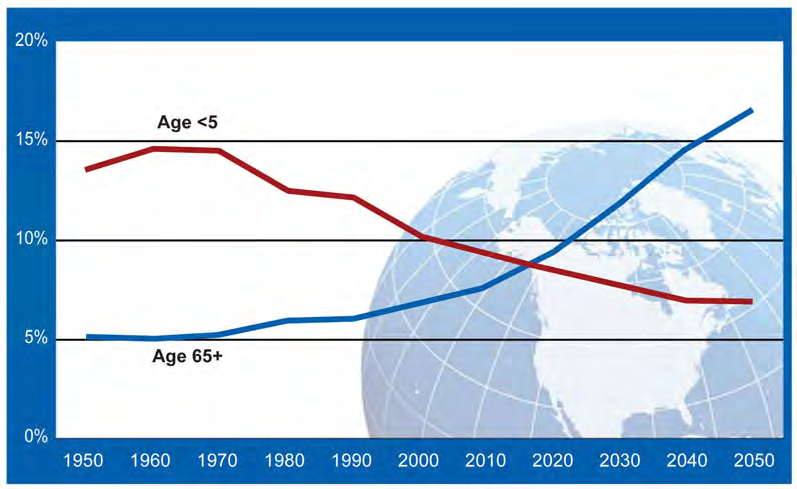

Most developed nations have had decades to

people in less developed countries is projected to adjust to their changing age structures. It took increase more than 250 percent, compared with

more than 100 years for the share of France’s

a 71 percent increase in developed countries.

population aged 65 or older to rise from 7

percent to 14 percent. In contrast, many less

This remarkable phenomenon is being driven

developed countries are experiencing a rapid

by declines in fertility and improvements in

increase in the number and percentage of older

longevity. With fewer children entering the

people, often within a single generation (Figure

population and people living longer, older

2). For example, the same demographic aging

people are making up an increasing share of the

that unfolded over more than a century in

total population. In more developed countries,

France will occur in just two decades in Brazil.

fertility fell below the replacement rate of two

Developing countries will need to adapt quickly

live births per woman by the 1970s, down from

to this new reality. Many less developed nations

Figure 2.

The Speed of Population Aging

Time required or expected for percentage of population aged 65 and over to rise from 7 percent to 14 percent

Source: Kinsella K, He W. An Aging World: 2008. Washington, DC: National Institute on Aging and U.S. Census Bureau, 2009.

4

Global Health and Aging

will need new policies that ensure the financial

security of older people, and that provide the

health and social care they need, without the

same extended period of economic growth

experienced by aging societies in the West.

In other words, some countries may grow old

before they grow rich.

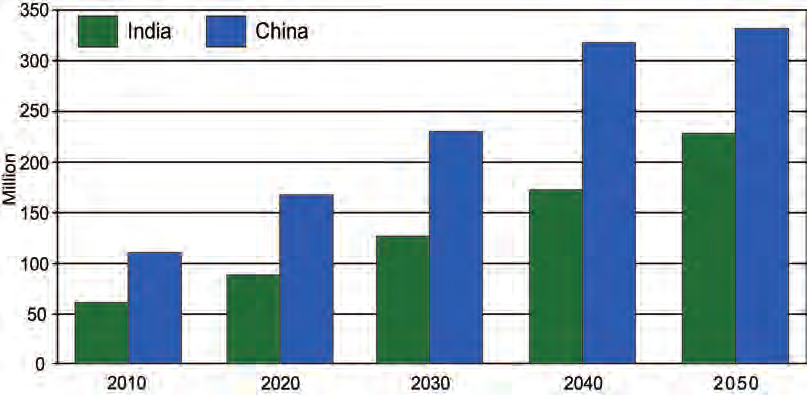

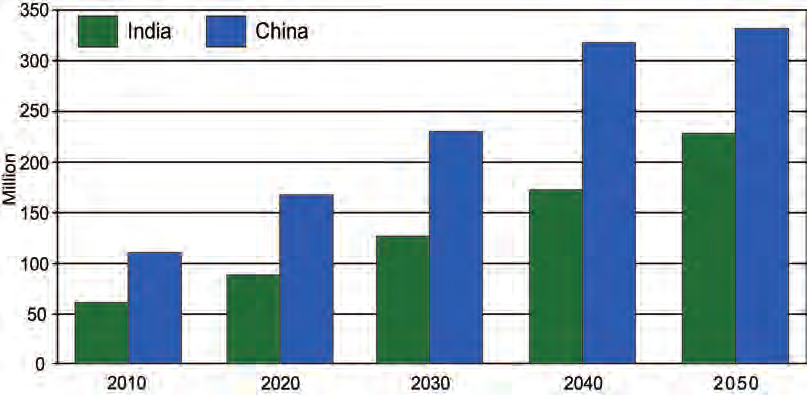

In some countries, the sheer number of

people entering older ages will challenge

national infrastructures, particularly health

systems. This numeric surge in older people is

dramatically illustrated in the world’s two most

populous countries: China and India (Figure 3).

China’s older population – those over age 65 –

will likely swell to 330 million by 2050 from 110

million today. India’s current older population

of 60 million is projected to exceed 227 million

in 2050, an increase of nearly 280 percent from

today. By the middle of this century, there

could be 100 million Chinese over the age of 80.

This is an amazing achievement considering

that there were fewer than 14 million people

this age on the entire planet just a century ago.

Crystal Craig | Dreamstime.com

Figure 3.

Growth of the Population Aged 65 and Older in India and China: 2010-2050

Source: United Nations. World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision.

Available at: http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp.

Humanity’s Aging

5

Living Longer

The dramatic increase in average life expectancy pathways. This transition encompasses a during the 20th century ranks as one of

broad set of changes that include a decline

society’s greatest achievements. Although most

from high to low fertility; a steady increase

babies born in 1900 did not live past age 50, life

in life expectancy at birth and at older ages;

expectancy at birth now exceeds 83 years in

and a shift in the leading causes of death and

Japan—the current leader—and is at least 81

illness from infectious and parasitic diseases

years in several other countries. Less developed

to noncommunicable diseases and chronic

regions of the world have experienced a steady

conditions. In early nonindustrial societies, the

increase in life expectancy since World War

risk of death was high at every age, and only a

II, although not all regions have shared in

small proportion of people reached old age. In

these improvements. (One notable exception

modern societies, most people live past middle

is the fall in life expectancy in many parts of

age, and deaths are highly concentrated at older

Africa because of deaths caused by the HIV/

ages.

AIDS epidemic.) The most dramatic and rapid

gains have occurred in East Asia, where life

The victories against infectious and parasitic

expectancy at birth increased from less than 45

diseases are a triumph for public health

years in 1950 to more than 74 years today.

projects of the 20th century, which immunized

millions of people against smallpox, polio,

These improvements are part of a major

and major childhood killers like measles. Even

transition in human health spreading around

earlier, better living standards, especially

the globe at different rates and along different

more nutritious diets and cleaner drinking

water, began to reduce serious infections and

prevent deaths among children. More children

were surviving their vulnerable early years

and reaching adulthood. In fact, more than

60 percent of the improvement in female life

expectancy at birth in developed countries

between 1850 and 1900 occurred because more

children were living to age 15, not because more

adults were reaching old age. It wasn’t until

the 20th century that mortality rates began

to decline within the older ages. Research for

more recent periods shows a surprising and

continuing improvement in life expectancy

among those aged 80 or above.

The progressive increase in survival in these

oldest age groups was not anticipated by

demographers, and it raises questions about how

high the average life expectancy can realistically

rise and about the potential length of the human

lifespan. While some experts assume that life

Berna Namoglu | Dreamstime.com

expectancy must be approaching an upper limit,

6

Global Health and Aging

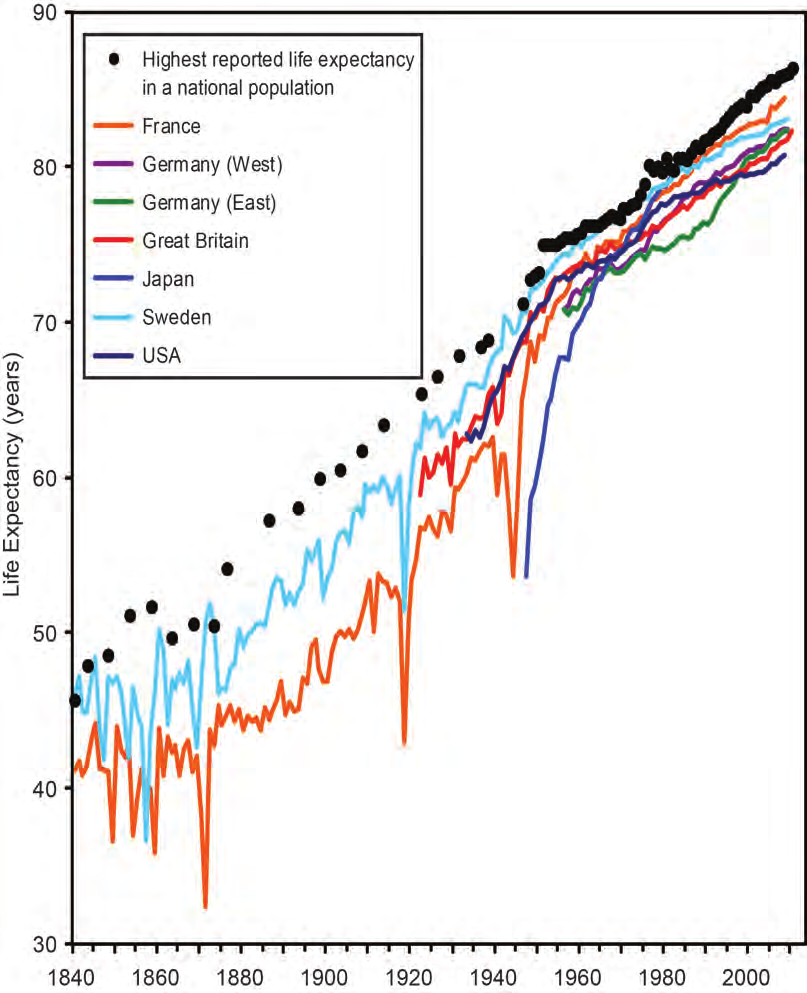

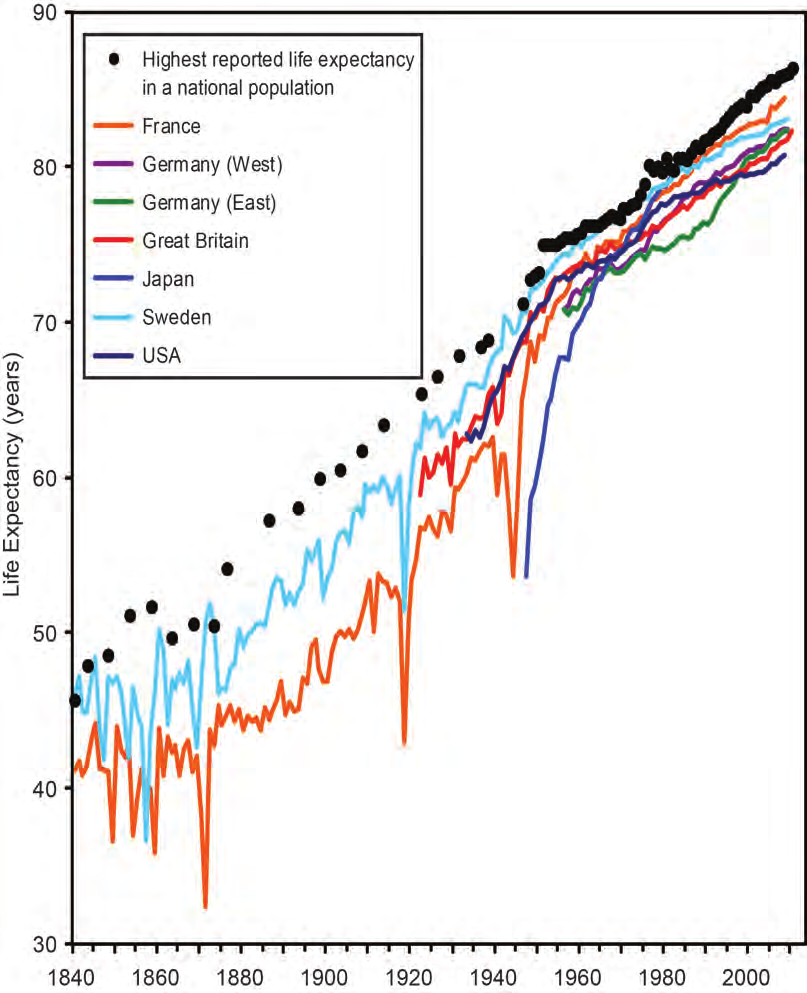

Figure 4.

Female Life Expectancy in Developed Countries: 1840-2009

Source: Highest reported life expectancy for the years 1840 to 2000 from online supplementary material to Oeppen J, Vaupel JW. Broken limits to life expectancy. Science 2002; 296:1029-1031. All other data points from the Human Mortality Database (http://www.mortality.org) provided by Roland Rau (University of Rostock). Additional discussion can be found in Christensen K, Doblhammer G, Rau R, Vaupel JW. Aging populations: The challenges ahead.

The Lancet 2009; 374/9696:1196-1208.

Living Longer

7

data on life expectancies between 1840 and 2007

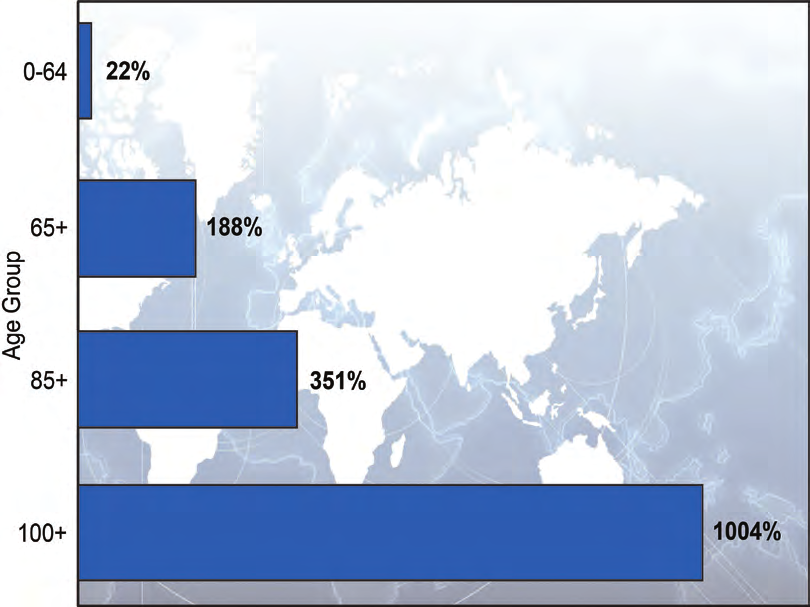

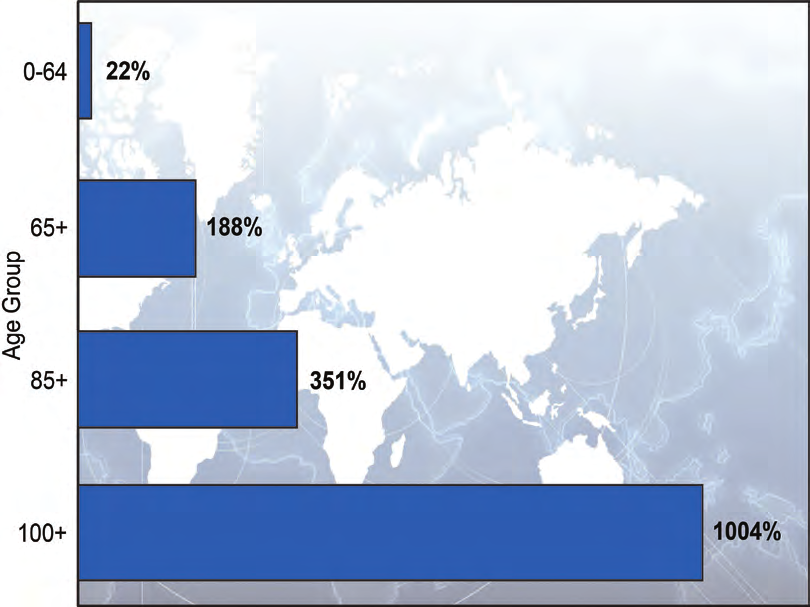

global level, the 85-and-over population is

show a steady increase averaging about three

projected to increase 351 percent between 2010

months of life per year. The country with the

and 2050, compared to a 188 percent increase for

highest average life expectancy has varied over

the population aged 65 or older and a 22 percent

time (Figure 4). In 1840 it was Sweden and

increase for the population under age 65 (Figure 5).

today it is Japan—but the pattern is strikingly

similar. So far there is little evidence that life

The global number of centenarians is projected

expectancy has stopped rising even in Japan.

to increase 10-fold between 2010 and 2050. In

the mid-1990s, some researchers estimated that,

The rising life expectancy within the older

over the course of human history, the odds of

population itself is increasing the number and

living from birth to age 100 may have risen from

proportion of people at very old ages. The

1 in 20,000,000 to 1 in 50 for females in low-

“oldest old” (people aged 85 or older) constitute

mortality nations such as Japan and Sweden.

8 percent of the world’s 65-and-over population: This group’s longevity may increase even faster 12 percent in more developed countries and 6

than current projections assume—previous

percent in less developed countries. In many

population projections often underestimated

countries, the oldest old are now the fastest

decreases in mortality rates among the oldest

growing part of the total population. On a

old.

Figure 5.

Percentage Change in the World’s Population by Age: 2010-2050

Source: United Nations, World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision.

Available at: http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp.

8

Global Health and Aging

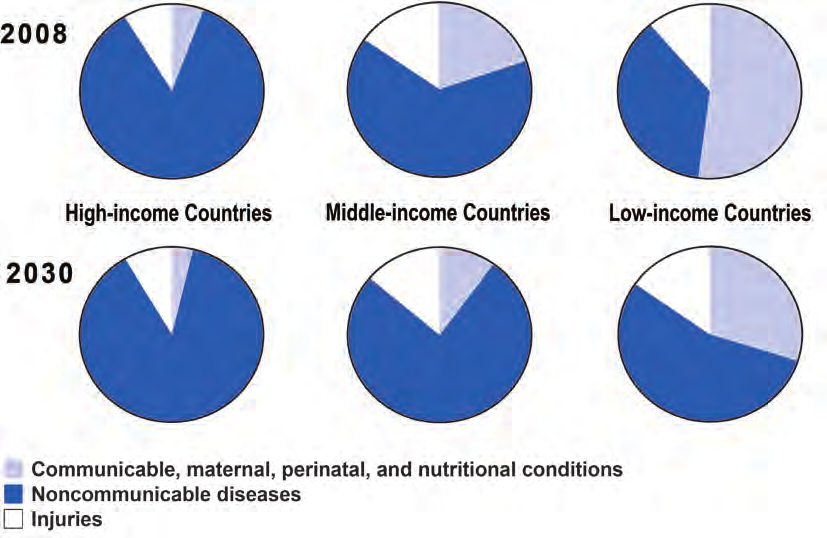

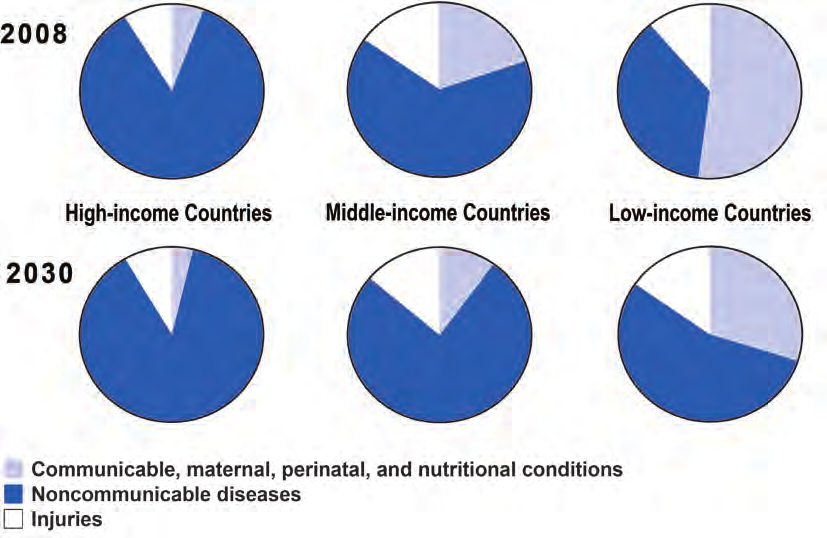

New Disease Patterns

The transition from high to low mortality

major epidemiologic trends of the current

and fertility that accompanied socioeconomic

century is the rise of chronic and degenerative

development has also meant a shift in

diseases in countries throughout the world—

the leading causes of disease and death.

regardless of income level.

Demographers and epidemiologists describe this

shift as part of an “epidemiologic transition”

Evidence from the multicountry Global Burden

characterized by the waning of infectious and

of Disease project and other international

acute diseases and the emerging importance of

epidemiologic research shows that health

chronic and degenerative diseases. High death

problems associated with wealthy and aged

rates from infectious diseases are commonly

populations affect a wide and expanding

associated with the poverty, poor diets, and

swath of world population. Over the next

limited infrastructure found in developing

10 to 15 years, people in every world region

countries. Although many developing countries

will suffer more death and disability from

still experience high child mortality from

such noncommunicable diseases as heart

infectious and parasitic diseases, one of the

disease, cancer, and diabetes than from

Figure 6.

The Increasing Burden of Chronic Noncommunicable Diseases: 2008 and 2030

Source: World Health Organization, Projections of Mortality and Burden of Disease, 2004-2030.

Available at: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/projections/en/index.html.

New Disease Patterns

9

infectious and parasitic diseases. The myth

Lasting Importance of Childhood Health

that noncommunicable diseases affect mainly

affluent and aged populations was dispelled by

A growing body of research finds that many

the project, which combines information about

health problems in adulthood and old age stem

mortality and morbidity from every world region