ARTY

STORIES

Book 2

THE RENAISSANCE

IN ITALY

The Patron & The Artist

Art and life

across the centuries

Ian Matsuda, FCA, BA (Hons)

for

Noko

Copyright

Ian Matsuda, FCA, BA (Hons), 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, transmitted or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher or licence holder https://www.artystories.org email: info@artystories.org

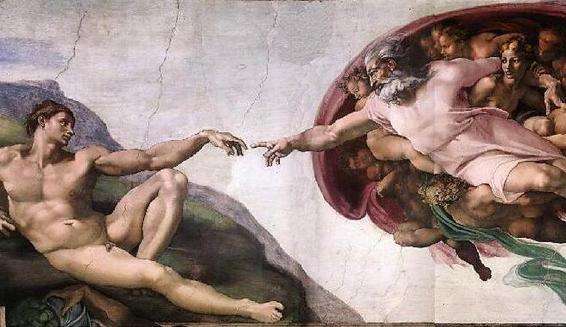

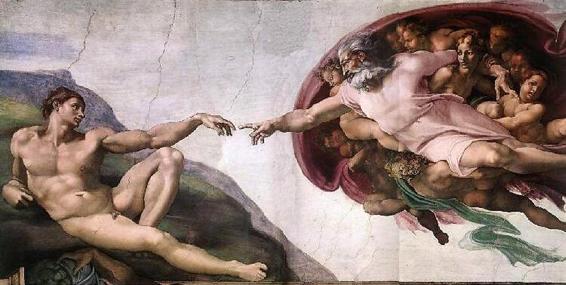

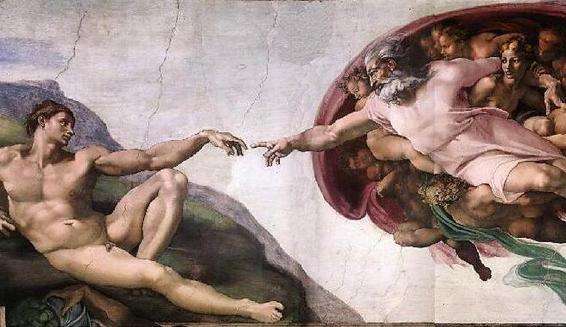

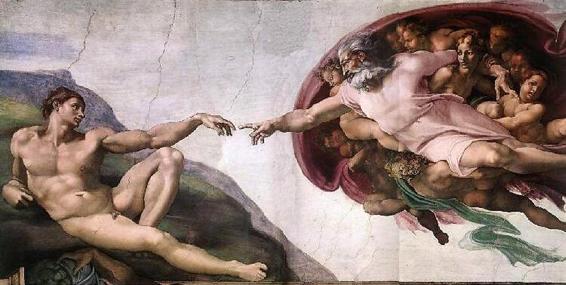

God giving life to man, Adam and is that Eve protected under his left arm?

Lady with an Ermine – 1489-90, National Museum, Poland

‘David’ by Donatello – 1440, Museo Nazionale, Florence

‘ARTY STORIES’

Art & Life across the centuries

‘Seeing people’s lives brings their art to life’

See the stories that made the art – the times – the place – the people Book 2: THE RENAISSANCE IN ITALY - The Patron and the Artist

A refreshingly entertaining introduction to the world of art through 5,000 years of tumultuous history This second book describes the Renaissance; or rebirth; of the great art of lost Empires, in 15th Century Italy.

New trading routes heralded new rich merchants who looked for art to raise their prestige, raising art to a rediscovered realism and beauty. Great artists flourished, new cities were raised, forging new, sophisticated cultures across Europe.

Leonardo, Michelangelo, Bernini - all designed buildings, carved sculptures and painted frescoes full of colour.

Ideal for student and art lover alike

Supported by the Arts Council, England as:

‘creative and engaging for young people’

‘the opportunities to stimulate interest and imagination are evident’.

Centuries of great art are a gift to us all

Books in this Series

Book 1 Egypt - Greece - Rome Empires come & Empires go 2 The Renaissance in Italy The Patron & The Artist

3 The Four Princes War, Terror & Religion 4 Northern Europe Revolution & Evolution 5 The American Dream Depression to Optimism

6 The Modern World The ‘..isms’ of Art

7 Past Voices Stories behind the Art All free e-book download

https://www.artystories.org

Book 2

THE RENAISSANCE IN ITALY

The Patron & The Artist

CONTENTS

• Lost and reborn in Italy

• Retelling history through art

• The great Italian artists – Leonardo da Vinci

- Michelangelo

• The Baroque & Bernini

• Summary

• Sources of information

Lost and reborn in Italy

Greece copied Egypt, Rome copied Greece and Italy copied their forefathers in Rome, calling it a ‘Re-naissance’

(re-birth) But all had very different societies and Medieval Italy was entirely new.

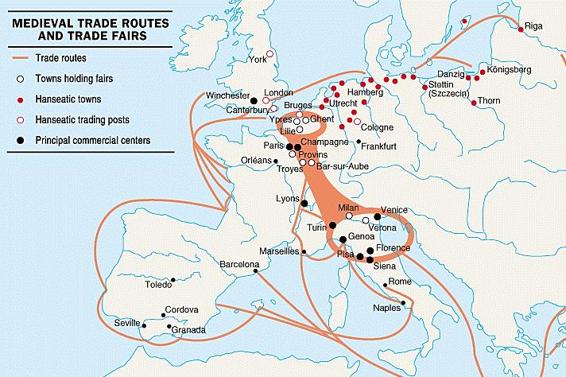

The culture and art of the Greek and Roman empires were to be lost for a thousand years, but were to be rediscovered in the renaissance in Italy. A dramatic and sustained increase in population across Europe with increased food, health and life expectancy, that all combined to drive a dramatic increase in trade. Newly rich merchants and bankers fuelled a demand for art. The art patrons had arrived.

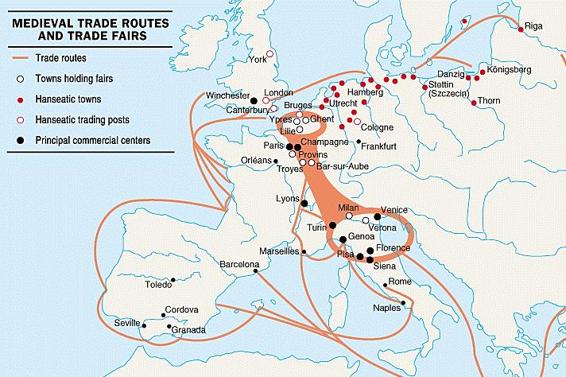

So by the 14th century, 900 years after the fall of

Rome, trade had recovered and again flowed

through the states of Italy. From Venice and

Florence and then on to France, the Netherlands and

England, even on to the Baltic. (1)

A rich circle of trade financed by powerful bankers

that grew to develop commercial contracts. These

wealthy families sought a status through the

perceived sophistication of art and soon their art

patronage eclipsed that of the Church or Aristocracy.

Art moved from the Church to the people.

Their wishes came to influence the nature of art.

Rich merchants and even richer bankers brought wealth to the cities and their new villas began to replace the old dark wooden houses. But, at night the cities were left in darkness with no streetlights and just a few very dim oil lamps in the major areas. The narrow side streets stayed completely dark and black, where you would need to carry a flaming torch to light your way home, amidst barking dogs, rattling carriages, and raucous shouting.

In this darkness the smells wafted of excrement, animal carcasses and rubbish, lifted by the smell of warm bread

Gradually the money from trade by the rich began to filter down to the lives of the poor and cities prospered. In Florence, even a peasant maid’s family would expect to offer money to persuade another family’s son to marry their daughter. It was more of an arrangement between families than an act of love, with lavish weddings. (2) Wives were expected to raise young boys to grow up to be healthy, educated young men and so more families could become successful and wealthy. An educated middle class was born.

Their children went to schools to study

Mathematics, Greek and Latin, with the

ancient sculptures and classical literature,

where art was valued in a virtuous life.

Realism in art was reborn, away from the religious taboos where the ban on ‘graven images’ had resulted in a cult of flat, un-natural images. This new art raised peoples’ aspirations and citizens rejoiced in this new culture, in which banking families were the leaders. The great cities of old were returning with a civic pride.

But it had taken a thousand years for these great cities to grow again, with their ancient art re-discovered (the

‘re-birth’, or as termed in French as the ‘re-naissance’). This new style was expressed as ‘humanism’ in a philosophy adopted across Europe to engage all citizens in an ethical, harmonious civic life and in its culture.

By the 15th century the ancient civilisations and art of the Greeks and Romans, had come to be admired and artists again went to schools of ancient art to study the beauty and realism of these works. Across Europe the church, aristocracy and the new wealthy merchants and bankers competed to be part of this ‘humanist’

sophistication. A sophisticated culture grew that is still admired today.

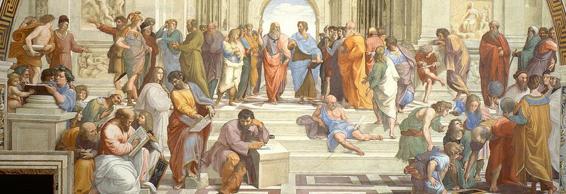

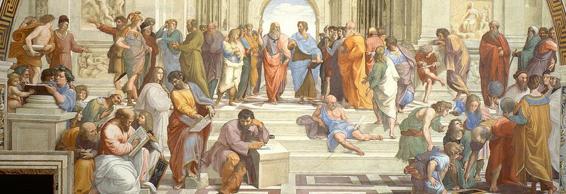

Seeing themselves as part of a new sophisticated social class, these wealthy patrons would go on to commission the best artists who could produce an art of beauty - true to life. The ancient Roman sculptures that still existed in Italy, provided examples and inspiration for the artists to sculpt with realism and balance. Great artists such as Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael and Donatello came to fame. This fresco by Raphael depicting Ancient Athens, symbolises the marriage of philosophy, art and science drawn from Ancient Greece.

Plato and Aristotle are dominant in the centre, whilst Raphael depicts himself lounging on the steps with Michelangelo at the foot, struggling to achieve perfection. The ancient philosophers and their values became the hallmark of the Italian Renaissance.

School of Athens, 1509-1511 Raphael, Apostolic Palace, Vatican City Artists designed buildings, created beautiful sculptures and painted great art. They were to transform cities and bring art back into ordinary people’s lives, providing a unifying culture on which to build a cohesive society.

But it was the patrons looking to secure their status in society and establish their sophistication across their European markets, who would fuel demand and determine the nature and style of the art.

You only have to look at one religious sculpture to see how realism was again embraced, even in churches. This sculpture from 1463 depicts the friends of Jesus rushing to him when they heard of his death.

With their head-dress and cloaks flying and

crying out in dramatic style, it was too detailed

to be carved in marble and was instead

modelled in clay and baked as terracotta

(‘baked clay’). It was then painted in vivid

colours, that have now long since faded away.

Sculpture was transformed into something

lifelike, dramatic and exciting. These women

are life size and seen rushing to find Jesus

dead. The excitement of the age has even

caused the church to change.

This realism is in contrast to previous religious

dogma and teachings and brought religion

directly into people’s lives rather than previous

portrayals of a heaven far away from this world.

Lamentation, Nicollo Dell’Arca, 1435-1440, Bologna

But, as we shall see, there was fierce competition between the independent states of Italy fuelled by the rich trade of powerful bankers and merchants, where power and control were everything.

Retelling history through art

Florence had become the richest state and so had the biggest army to wage a string of wars between states. In this bustling 15th century, the Medici banking family had used their great wealth to gain control of Florence.

The Medici’s family’s wealth came both from trade and from managing Church money across Europe. (11) View of ancient Florence, by Probst

The rich could now afford to have art made that reflected their power and status and so their version of history.

They wanted to show the world the superiority of Florence across the region and display their fine tastes. They aspired to be recognised as the wisest and most cultured across Europe and so they sent out for the best artists to make the best works of art. These were to emulate the grace and realism of Ancient Greece which was now the standard throughout the European aristocracy. As they competed amongst themselves to be the best and the most cultured, they often ordered different versions of the same subject, to suit their personal standing.

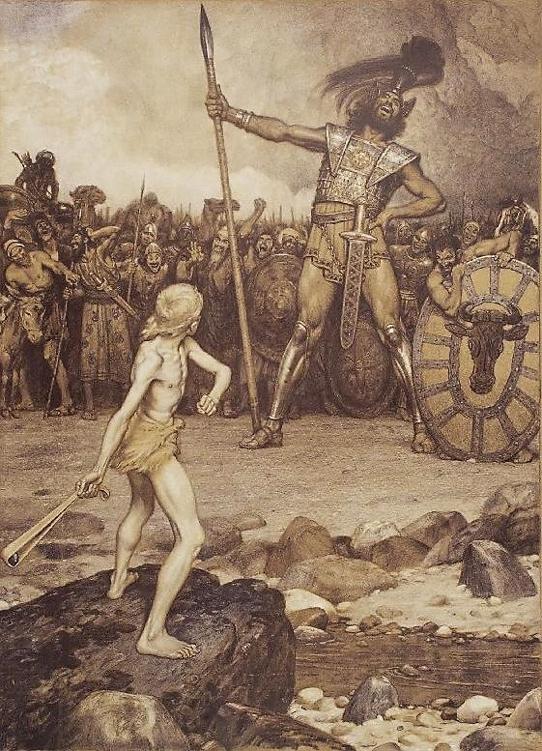

An example is in the varied statues of ‘David’.

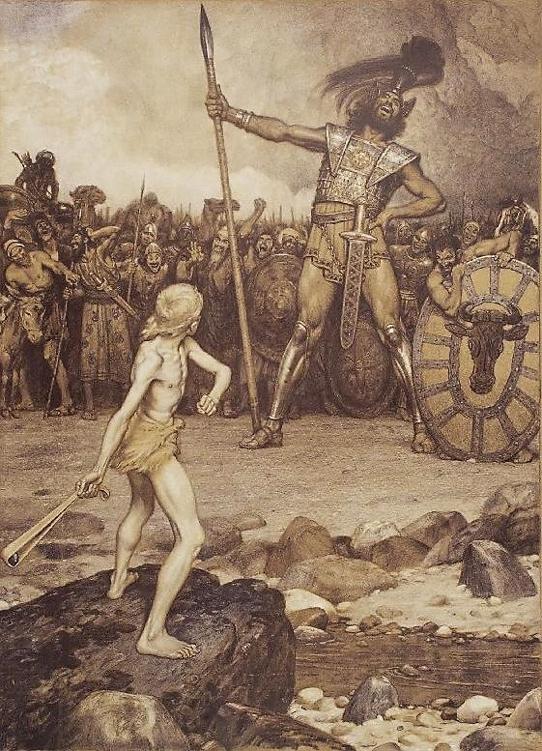

Sculptures often celebrated great events from the past and the battle between David and Goliath was one that celebrated the power of good over evil. The battle had taken place some 2000 years earlier, but the story was well known as it had been celebrated in the Bible and so read out in church. Celebrating how the Israelites (Jews) defeated their enemy, the invading Philistines, the legend demonstrates how the ‘few’ can defeat the

‘many’. This was very relevant to the many Jewish bankers who were a minority in Italian society.

A shepherd boy David went out armed with just a sling to meet the

Philistine champion Goliath, who had challenged the Israelites to settle the war by single combat. Goliath was a giant, carrying a huge sword and spear and towering over David. The mighty threaten the small.

Picking up some stones David walked bravely forward, throwing down

his armour. The Philistines laughed and then, as both armies looked on hushed, David spun his sling above his head and before Goliath could use his mighty sword, launched his stone. He struck Goliath in the

middle of his forehead and he crashed to the ground, dead. David cut off the dead giant’s head and held it aloft. Seeing their leader killed so easily, the Philistines fled the battlefield and Israel was saved.

Courage and right were rewarded.

The Renaissance philosophy praised individual values of honour and

glory in this life, rather than being merely a gateway to an afterlife.

Antique print, 1900, Schindler

But the character of David was open to interpretation.

The church in Italy dominated people’s lives and the rich wanted to secure their place in heaven. This story of the triumph of good over evil was known by everyone and artists were paid by rich merchants to celebrate this biblical victory and so secure their place in heaven. As a result, there is more than one sculpture of David and each one was ordered by a different patron and made by a different artist and each shows a different story that each wanted to portray. Patrons were deciding the nature of art.

The first was by ordered by the banker Medici who controlled Florence, to show his perfect taste.

He sought the best sculptor of the time, Donatello who portrays a

young and slim life size portrayal of David, victorious after the

battle. This delicate style was very different from other sculptures of the time. David looks down at the head of Goliath that lays at

his feet and prods it with Goliath’s sword. The message was that

the Medici family were always victorious and were the leaders in

style and society, not just cold mercenary bankers. The sculpture

was made in bronze and could be polished to shine with the

beauty of David. This life-size work stood in the courtyard of the

banker’s house for all their guests from across Europe to admire

and so admire the Medici. Daring to be the first nude sculpture in

Florence and clearly effeminate, they invited controversy, further

demonstrating their unchallenged position in society.

‘David’ by Donatello – 1440

Museo Nazionale, Florence

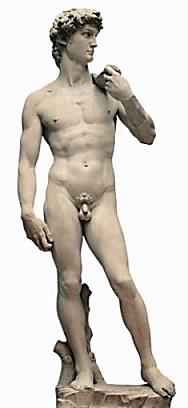

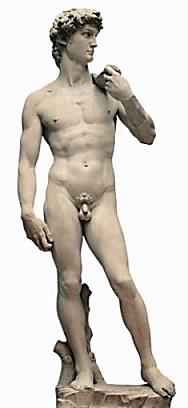

And then later there is Michelangelo’s idea of a proud, but tense David before the battle and is the most famous. The first huge nude since antiquity, this was a daring sculpture on which he laboured for 4 years.

Cut from a single block of marble that had lain neglected for 40 years as other sculptors were put off by flaws inside the block, Michelangelo worked secretly day and night inside a black tent. This huge sculpture stands 17

feet high, a tremendous three times the size of other life size sculptures. It was made to sit on the top of the roof of the Duomo, Florence’s cathedral.

As a result, when you look at the sculpture from ground level, David’s head seems bigger than you’d expect. But when you look up at the sculpture from underneath; as you would have done if it was on the roof; then it all looks in proportion. It had to be big to be seen from the street below. But, then no one could lift this huge 6 ton sculpture up on to the roof and so instead it stood in a public square outside the governors’ offices, who had

commissioned the statue. Ironically this was closer for the people to admire and all the better to announce to the states all around Florence that the hero David was a symbol of the peoples’ strength and would protect and overcome all enemies.

Completed in 1504, it was not until 1873 that it was moved inside a gallery.

‘David’ by Michelangelo – 1504, Galleria Dell’ Academia, Florence

Next came a sculpture by Bernini who was aged just 24. (see later)

Again, life size and shows David in the moment of launching the stone. David had thrown aside his armour as he advanced on Goliath and it lay at his feet.

This marble sculpture does not have the grace and beauty of the earlier bronze work, but is all power and action as it steps out into the viewer with a strong, determined look. This powerful image was ordered by a church Cardinal for his villa and stood as a statement of his power.

‘David’ by Bernini – 1624 Galleria Borghese, Rome

Three sculptures portraying David before, during and after the battle for three different patrons who each chose their own version of the ‘reality’ of that event and of that person. It was the rich merchants or the church who decided what people see and believe. History can be influenced to present a particular interest. As Winston Churchill said: ‘History is written by the victors’.

Even today we see individual and corporate wealth determining architecture in our cities and supporting new art galleries, displaying an art designed primarily to attract visitors and so enhance their status in society.

With the demand for their work, together with architectural commissions for imposing grand buildings, Renaissance artists thrived. Art began to again enhance cities as in the Greek and Roman world of old.

The great Italian artists – Leonardo da Vinci

This same revolution of a renaissance in realism and expression that was seen in sculpture, was also expressed in paintings, although they still portrayed perfect and ideal figures. Where previous paintings had looked ‘flat’, now they had depth – perspective – giving the illusion that you are looking into a real scene. This was coupled with a burst of wonderful colour in paintings on church walls and then on canvas. As Popes, Kings, Emperors, Dukes and the new rich merchants and bankers competed for the best, art was raised to new levels and artists became revered for their skill. The Medici family who commissioned the sculpture of David, now had a banking business that extended from Italy up to the north at Bruges, in the Netherlands. Bruges was the leading centre for the wool trade and so became a major trading city as well as an art centre for Northern Europe. The Medici had a long and powerful reach across European countries and so influenced tastes across varied societies.

While the Italian states fought between themselves both in battle and in trade, they were also rivals to be the most cultured and so were also in competition for the best artists. As art became exclusive to the richest and the most powerful, art became political as a projection of ‘soft power’ to assert their position. But this also brought beauty and pride to the cities and unified societies emerged, creating stability and bringing business and increased wealth. Other new artists seized these opportunities and more works became more freely available.

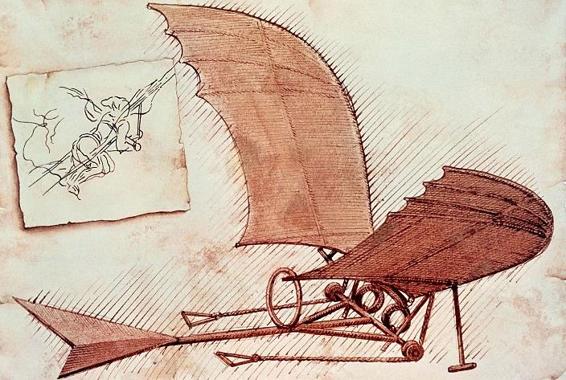

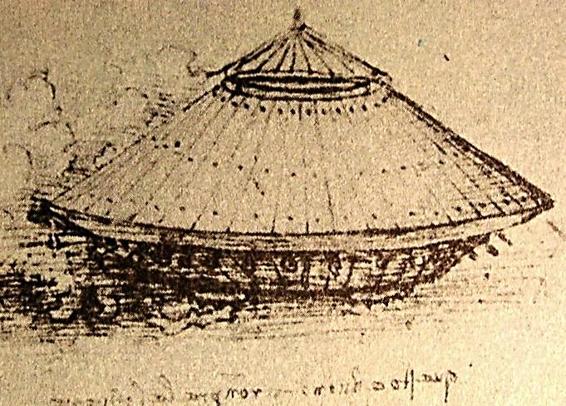

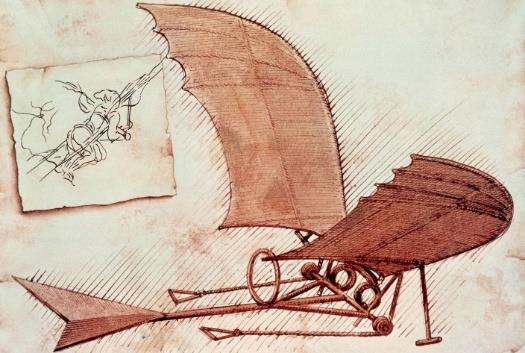

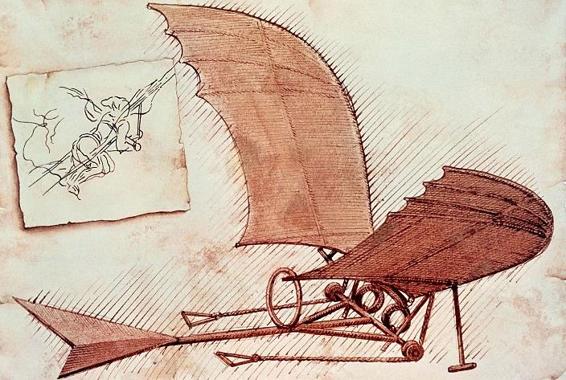

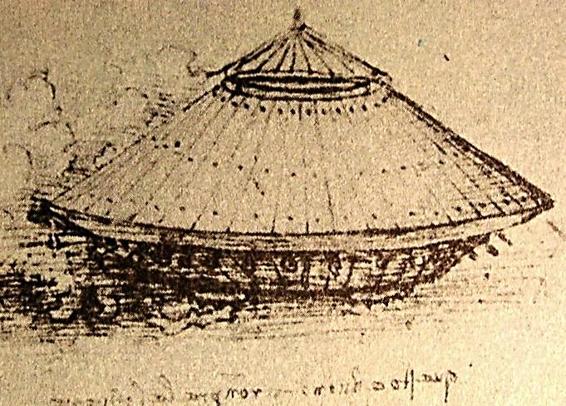

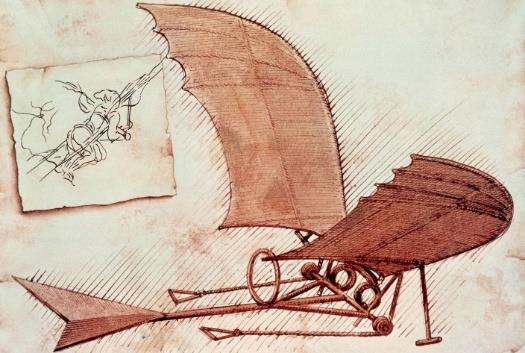

One of the most gifted of these artists was Leonardo da Vinci who became an apprentice to the famous painter Verrocchio. Although entirely self-taught, his early work so impressed that it is said that Verrocchio never painted again. Leonardo not only produced great art, but complemented this with the science of the Renaissance, designing military weapons for the wars. He drew the first flying machines, engineered canals to divert rivers and even composed music. This range of talents made him attractive to the rich and powerful, where his exceptional musical skills enhanced their own status in society. The Duke of Milan realised this when Leonardo worked for him from 1482 to 1499. ‘Worked’ is debatable as in those 17 years Leonardo was so pre-occupied with his ideas, that he produced just 9 paintings and not all for the Duke. It seems that Leonardo preferred the process of concept and invention, rather than the finished work. (4)

He invented armoured fighting machines (tanks), canons and catapults to breach city walls and barricades to protect them. He designed double hulls to protect ships and even flying machines to hold a man.

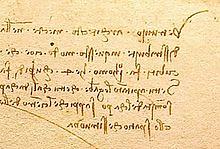

But most were never to be built as the technology to build them had not kept up with his ideas, which were way ahead of his time. The Duke of Milan would have relished these advances as his family fought wars with an advancing Venice and then under siege from France, only to be rescued by the Habsburg Empire. (Book 3) Leonardo was so keen to keep his inventions secret that he wrote in a mirror image, so to read his writings you had to look at the words in a mirror.

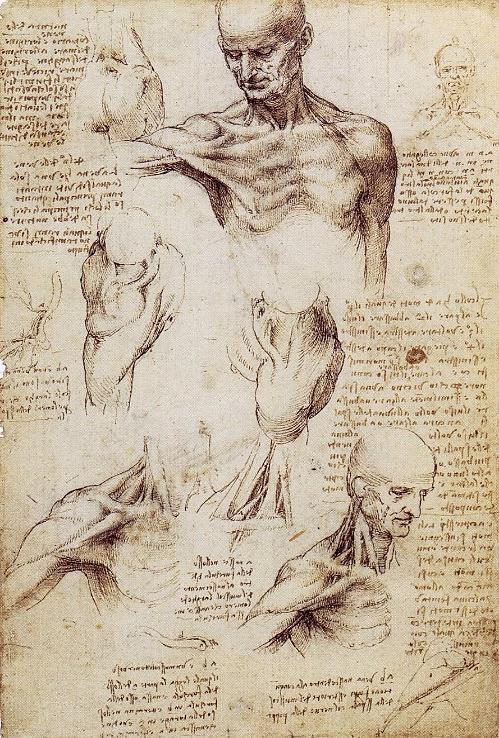

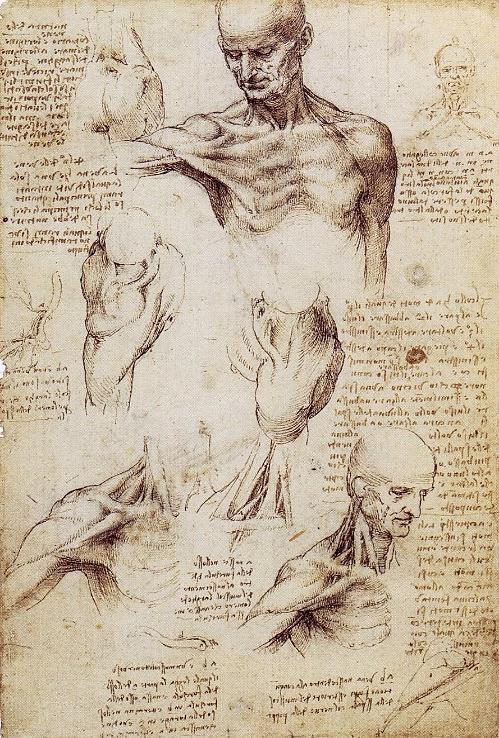

Although Leonardo considered himself a creative visionary and inventor, his studies of the workings of human and animal bodies meant that his art was true to life.

The description ‘genius’ can well be applied to Leonardo. He had so many ideas that a collection of 30,000

pages of his notes can be seen today in a chateau in Amboise in France. On the invitation of Francis 1 he had retired there for 3 years before he died aged 67 in 1519. His creativity can be seen in his famous, but few artistic works, which show us his true genius in capturing the character of the sitter. Being so innovative, he was among the first Italians to use the Dutch invention of painting with oils on canvas, allowing more vibrant colours.

As Leonardo was known for the use of vibrant colours - even in his own clothes - the Parisian Mona Lisa now cracked and yellow with age, may not be a true depiction of his work. A copy in Madrid made by an apprentice of Leonardo, may show a different view. This was very possibly made in the studio at the same time, but not subjected to the heavy varnishing used in later restorations. Similarly, his depiction of The Last Supper is even more degraded, but again an apprentice’s copy in London, illustrates shows the true colours. (5) We can see this colour in another earlier work by Leonardo, Lady with an Ermine, arguably with more personality and life than the later Mona Lisa.

Mona Lisa – 1503-06 Mona Lisa copy – 1503-06 Lady with an Ermine – 1489-90

Louvre, Paris Prado Museum, Madrid National Museum, Poland Mona Lisa was commissioned by a Florentine silk merchant, of his wife Lisa del Giocondo, but he was never to receive the finished work. Leonardo kept the painting for himself for the rest of his life – why? He had a tendency to tinker with his paintings, sometimes over years or perhaps her calm, knowing smile hides a secret love that grew between them while Mona Lisa was sitting for Leonardo. He never married and shortly after left Florence, never to return. Is there a little sadness in her smile? The earlier Lady with an Ermine (6) has more movement and as if surprised by someone else entering, again with far more colour. This beautiful painting depicts the mistress of the Duke of Milan. He was a member of the prestigious Order of the Ermine and so the ermine (stoat) on her lap, which is also a symbol of the lady’s purity. Here, the light falls on her face, to draw you in to her thoughts, in contrast to the Mona Lisa, who hides her thoughts.

So, what makes a work of art famous, the artist’s work or public opinion? Well the Mona Lisa was stolen in 1911

and until its return in 1913, had a lot of publicity in the newspapers, when it then became famous. However, Lady with an Ermine and the recently discovered colour contemporary copy of the Mona Lisa, have hardly been mentioned in the press and so are less well known. Art is very personal and perhaps each viewer should decide, although opinions can be influenced by institutes, promotional articles and events.

The great Italian artists -Michelangelo

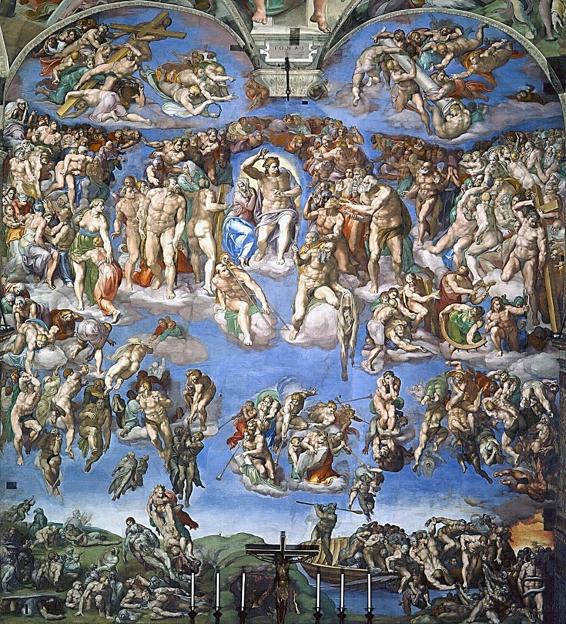

Now let us look at Leonardo’s fierce rival in what is probably the biggest painting in the world by Michelangelo in 1512, covering ceilings and walls in the huge hall of the Sistine Chapel in Rome. No greater painting can there be than this soaring fresco depicting the story of the creation of man in the heavens. Then the contrast of man’s subsequent downfall in the later adjacent wall painting of the ‘Last Judgement’, portraying the horror of hell.

As the wars between the Italian states subsided, the popes had returned to Rome 100 years earlier and set out to rebuild the city and its cultural heritage. The church had amassed great power and money by using its Papal armies to secure lands and had brought the churches in other European countries back under its control. The people had to go to the church and pay for their prayers (termed ‘indulgences’) to forgive their sins and reserve their place in heaven with a dread of hell. The church and the Pope became the highest authority and as the priests were held to be the only ones who could talk to God, they held a continuing source of power over people and over kings and emperors across Europe. A source of great power and wealth that Martin Luther was to teach against in 1520 in Germany and why Henry Vlll was to break away from the Catholic church in 1532.

This monopoly of religious power, so important to peoples’ lives, was to lead to what transpired to be more than 100 years of the wars of the ‘Reformation’, that brought so much terror and suffering across Europe. (Book 3)

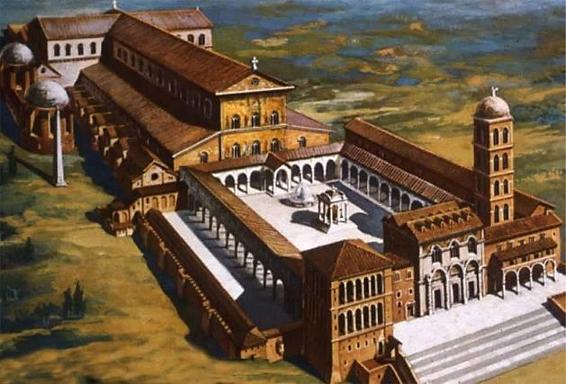

As Rome again became rich and powerful, bankers, merchants and pilgrims returned to benefit from its power.

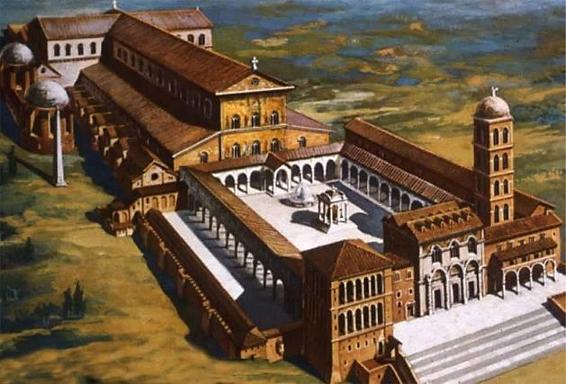

This power and wealth was used by successive popes to rebuild the ruins of Rome, neglected for over 1000

years. They started with the tired old Roman church that was collapsing and by the 16th century they had replaced it with a great new church in white marble, standing on a hill and dominating all of the people of Rome.

Impression of ancient St Peters, from 360AD ‘New’ St. Peters, 1506

Once the new church was built and it became the Catholic centre for Europe, they needed the very best works of art to raise its prestige. With his power, Pope Julius lll virtually forced Michelangelo to give up his other work. From 1508 -1512

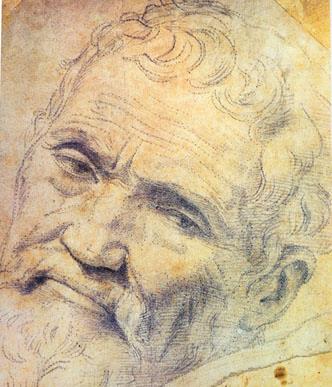

he devoted four years of backbreaking effort to paint his Sistine Chapel in the rebuilt St Peters. Michelangelo saw himself as divine, with a god given talent.

But Michelangelo was reluctant at first, insisting that he was a sculptor not a painter. However, the more he thought about it, the more he saw the tremendous potential and was so excited that he isolated himself in the chapel. He threw out the Pope’s design and for four years he refused to let anyone in to see the progress, for fear of being copied. In a display of arrogance, he even refused entry to the Pope who was the most powerful man in Italy and in Europe.

Sistine Chapel, 1508-1512

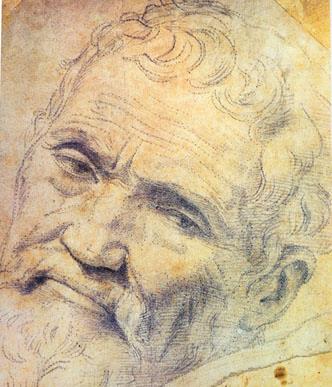

The ceiling tells the story of the creation of man by God, depicted in the central panel. On the right side is God’s creation of the world, the parting of the seas from the land and setting the stars and planets, bringing light to the earth and then the creation of man. But man lost this perfection, leading to the downfall of Adam and Eve. (7) The beauty of this work is in contradiction to the life of Michelangelo himself, who lived in squalor, eating only out of necessity and often going to bed in his boots and clothes, as he did when painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling. This was emphasised by his looks, being quite small, with a broken nose from a student fight. He had a reputation for ugliness, which may have discouraged self portraits. His life was not one of socialising, but of dedication and he dedicated himself to an obsessive search for perfection.

God giving life to man, Adam and is that Eve protected under his left arm?

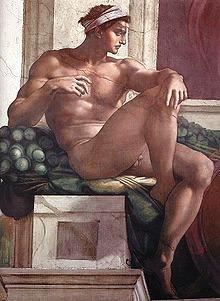

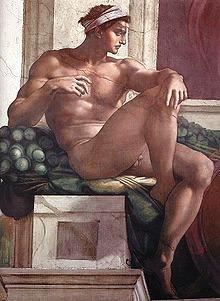

Delphic Sibyl with her scroll of phrophecies Male athelete, ‘The Ignudi’ The damned going down to hell She would tell the future one of 20 guarding the saints They had no future !

Michelangelo used bright colours so that these huge expressive figures could be seen from the floor, more than 20 metres below. We are now able to see these original colours due to a ten-year restoration project, completed in 1994. The whole chapel is 40 meters long and the ceiling painting covers over 460 sq. meters, with over 300

figures, each 3-4 times life-size. This was not so much a painting as a work of supreme physical endurance.

To realise this work of painting a ceiling, Michelangelo had to either stand and bend backwards or lie on his back and twist his neck, with paint dripping down on to his face and beard. Working in such a cramped space, he became locked in that position and even read his letters lying down. Perched on scaffolding 60 feet up in the roof, the pain and effort were terrible with the cold freezing his hands in the winter and in summer enduring the stifling heat, Michelangelo’s self-belief and determination to show his divine genius, drove him to exhaustion.

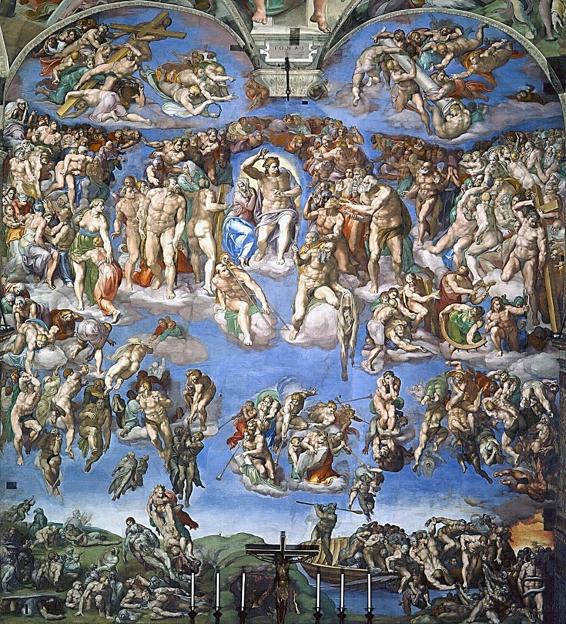

Then Michelangelo returned 24 years later to again paint a massive work on the end wall, this time showing hell.

This huge work of 14 by 12 metres, took Michelangelo

another 4 years and he was almost 67 by the time he

had finished. The painting shows the last judgement with

Christ and Mary in the middle, surrounded by saints.

On the left those who had lived good lives are ascending

with the angels to heaven. On the right are the damned

who had led bad lives, being rowed across the river

Styx, to descend into the horror of the underworld.

This is how you encouraged people to live good lives

and to obey the church and its laws, keeping society

honest and under control, in a fear of God.

But the Catholic world was about to change as people

across Europe broke away from the authority of Rome

and the Church wealth was to diminish. (Book 3)

The Last Judgement, 1536-1541 Michelangelo

Amazingly, between these two great works, Rome had been sacked by rebel soldiers of Charles V, in a terrible siege that decimated the population of Rome. The Pope was imprisoned and forced to appoint Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor. His rigid Catholicism was to crush the free-thinking principles of the Renaissance. The terrors of the Spanish inquisition were to follow and Europe was to enter 100 years of wars. (8) and (Book 3)

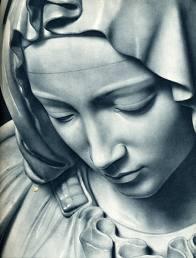

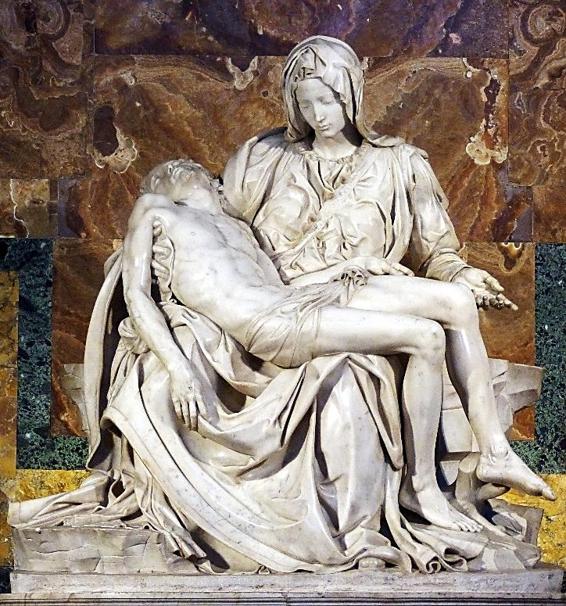

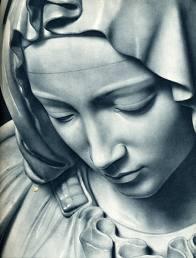

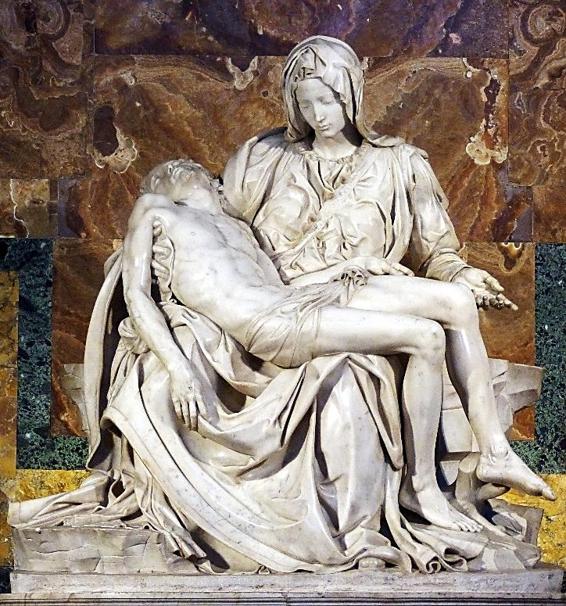

Michelangelo’s skill as a sculptor is clear in his statue of David (see earlier), aged just 23, he had already produced a delicate carving of Mary with the crucified Christ laying across her lap in La Pieta; ‘the Pity’.

Commissioned by a French cardinal for his memorial, this also now stands in St Peters in Rome.

Michelangelo portrayed Mary as youthful because as she had stayed a virgin, she would stay youthful. We can see his obsessive search for perfection, even in this early work, where the strength and love of Mary for Jesus, signifies the love and protection of the Church.

La Pieta, Michelangelo, 1499 The folds in the skin and dress A loving gaze St Peters, Rome

In the Renaissance tradition, Michelangelo was also an exceptional architect where he was appointed Chief Architect of St Peters and designed the exterior columns and dome, although this was modified after his death.

The ‘Renaissance’ was to evolve into the ‘Baroque’ style where greater flamboyance and energy was championed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, who had sculpted the powerful statue of David. (see earlier)

The Baroque & Bernini

Bernini was a man of many parts as playwright, architect and city planner, but is remembered mostly for his sculptures. His skill in manipulating marble marked him as a worthy successor to Michelangelo, even from the age of 8. His rise was predicted and eagerly awaited. Between 1619 to 1625, aged just 21-27, he introduced himself with four sculptures, heralding a new era in European sculpture.

As with his ‘David’ (see earlier), his work exuded emotion, enhanced by theatrical compositions in a flamboyant style, with a technique and skill equal or greater to any sculptor who had gone before. (8) Here, the virgin Daphne is pursued by the God Apollo, only to turn into a tree at the point of capture. (see her hands) His fame attracted the Church where the Pope commented ‘You are made for Rome and Rome for you’, granting him a near monopoly on papal commissions, designing the famous square and colonnade in front of St Peters.

Apollo and Daphne, 1622-1625, Gian Lorenzo Bernini

Within the St. Peters Basilica he created a dominating

centrepiece with a spiralling gilded bronze canopy. This

strode over the high altar and the tomb of St. Peter, in an

ornate style that would come to define the baroque.

Nothing like it had been seen before.

St. Peters Baldacchino, 1626, Gian Lorenzo Bernini

Bernini worked up to two weeks before his death in 1680,

aged 81, the father of the Baroque.

Summary

Firstly, how Greek sculpture was reborn in Italy with the Renaissance and how the Kings and Emperors all over Europe wanted to own these exciting and stunning new works.

We saw how the wealth of rich merchants and with the church, each looked to project their power and status in society, reflected in the different portrayals of their sculptures.

This success revitalised cities and new civic pride attracted further business and wealth In commissioning a work, the patron can determine how the artist portrays the subject and so the patron can influence the public’s perception of both himself and of the society that they live in.

Status in society can be a driving force.

The patron influences the art and the art influences society

Leonardo da Vinci’s few works of art have achieved fame both by their exquisite technique and also by the fame generated in media, often influencing the public’s opinion. The copies made at the same time by his apprentices, may provide a truer picture.

Then Leonardo’s futuristic inventions; many of which were only realised 400 years later in the 20th century and show the levels of creativity reached by him in the 15th century, although never realised.

How the church became so rich it initiated a rebuilding of the city of Rome and demanded the best artists to come to decorate it. This led to the Pope’s ambition to commission the huge work by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel, that defies the human spirit.

Then the evolution to the flamboyance and theatrical compositions of the Baroque that provided sculptures charged with vitality and emotion.

A renaissance that heralded a new society and culture and inspired art that takes our breath away today.

Sources of information

(1)

https://www. metmuseum.org>trade>Roman_Empire

(2)

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/wedd/hd_wedd.htm

(3)

https://www. pbs.org/empires/medici/medici/bankers.html

(4)

https://www. da-vinci-inventions.com

(5) https://en. wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Last_Supper_(Leonardo)

(6)

https://www.totallyhistory.com/lady-with-an-ermine

(7)

https://en. wikipedia.org/wiki/Sistine_Chapel_ceiling

(8) https://en. wikipedia.org/wiki/Gian_Lorenzo_Bernini

A BBC series ‘Civilisation’, provides a history of art and society

from the middle ages to the present day, over 13 episodes

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLXC6RzjHc2wugLza1kMWN_CRBuKRqQNTw

Books in this Series

Book 1 Egypt - Greece - Rome Empires come & Empires go 2 The Renaissance in Italy The Patron & The Artist

3 The Four Princes War, Terror & Religion 4 Northern Europe Revolution & Evolution 5 The American Dream Depression to Optimism

6 The Modern World The ‘..isms’ of Art

7 Past Voices Stories behind the Art All free e-book download

https://www.artystories.org

The history of life and art across centuries,

of changing societies and changing cultures.

‘I think the concept for your work is both

creative and engaging for young people.

The links between art, history, society

are clear in the outline you provide and

the opportunities to stimulate young people’s

interest and imagination are evident’.

Sir Nicholas Serota,

Chairman, Arts Council, England

Society makes art

and art defines society’s culture

Lamentation, Nicollo Dell’Arca, 1435-1440, Bologna