ARTY

STORIES

Book 6

THE MODERN WORLD

The ‘..isms’ of Art

Art and life

across the centuries

Ian Matsuda, FCA, BA (Hons)

for

Noko

Copyright

Ian Matsuda, FCA, BA (Hons), 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, transmitted or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher or licence holder https://www.artystories.org email: info@artystories.org

‘Futuristic Motorcycle’, Fortunato Depero, 1914

The Persistence of Memory, Salvador Dali, 1931

‘ARTY STORIES’

Art & Life across the centuries

‘Seeing people’s lives brings their art to life’

See the stories that made the art – the times – the place – the people Book 6: THE MODERN WORLD – The ‘…isms’ of Art

A refreshingly entertaining introduction to the world of art through 5,000 years of tumultuous history This sixth book enters a 20th Century where a kaleidoscope of new art thrust into the scene with their descriptive ‘…isms’.

The carnage of a first World War forced upon the people, realised protest across the world for a new, peaceful way –

expressed in new ‘futuristic’ art. Artists rejected traditional styles and explored their own inspirations, that reflected this new mood. Futurism, Cubism, Surrealism, Dadaism – Picasso, Dali, Warhol, all had their own perceptions in this maze and all their own supporters or detractors. Art became entertainment and each generation has its heroes.

Ideal for student and art lover alike

Supported by the Arts Council, England as:

‘creative and engaging for young people’

‘the opportunities to stimulate interest and imagination are evident’.

Centuries of great art are a gift to us all

Books in this Series

Book 1 Egypt - Greece - Rome Empires come & Empires go 2 The Renaissance in Italy Rulers rule, Painters Create 3 The Four Princes War, Terror & Religion 4 Northern Europe Revolution & Evolution 5 The American Dream Depression to Optimism

6 The Modern World The ‘..isms’ of Art

7 Past Voices Stories behind the Art All free e-book downloads

https://www.artystories.org

Book 6

THE MODERN WORLD

The ‘..isms’ 0f Art

CONTENTS

• The ‘..isms’ of Art

• Four artists and Futurism

• Pablo Picasso & Cubism

• The Great Depression

• Salvador Dali & Surrealism

• Warhol, Emin & Dadaism

• Summary

• Sources of information

The ‘...Isms’ of Art

Modern Art for a Modern World

The 20th century heralded new industrialised societies with a new middle class defining the new world for themselves, such as the adoption of impressionism against the upper-class art ‘establishment’. (Book 4) Artists were seen as the bohemian voice of society and free to express extreme opinions. Their art not only challenged traditional forms of art, but some saw themselves as a protest movement against bourgeois interests and the cultural values that shaped society, which they believed led to the First World War of 1914-18.

This was a time of great change as the war shook societies throughout Europe with 15-19 million deaths and 23

million wounded military personnel. It was the people who suffered and who termed it as ‘the war to end all wars’. The great empires of Russia and Austria fell and everywhere democracy was established as the people vowed never again to be taken to war by their rulers. But as we shall see, it would happen again.

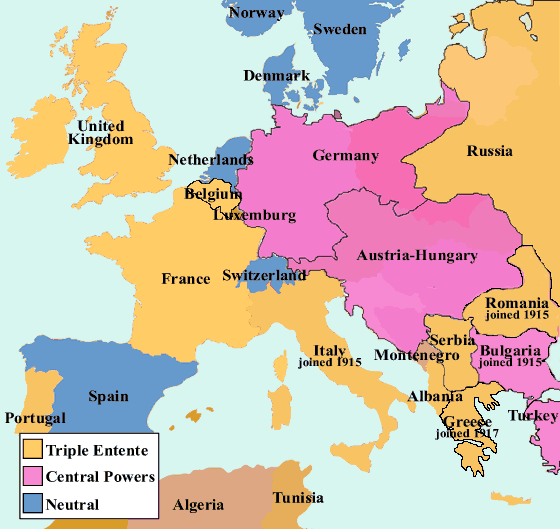

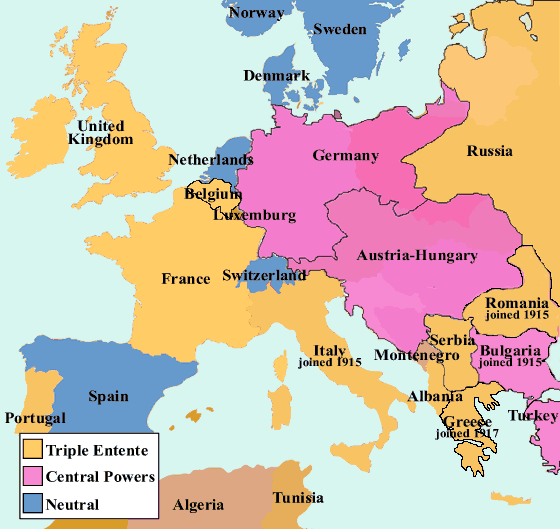

The First World War had been triggered by the assassination of the Emperor of the fading Austro-Hungarian Empire, by a Bosnian-Serb nationalist. The Empire decided that retribution must be made and set out to invade Serbia, who were Russia’s friends and who in turn declared war on the Empire. Germany rushed to the Empire’s defence declaring war on Russia. France had agreed to support Russia and so joined in. Germany then moved against France through Belgium, who Britain had agreed to support and so Britain joined in, creating a Russian, French and British axis, or ‘entente’. War now covered Europe to the bewilderment of the people, who were suddenly told that friends were now enemies. (1) Europe in the First World War

Mistrust between nations and a breakdown in diplomacy were to reap a dreadful cost on the men called to the fight, in a supposed defence of their nation. Nationalism was to pay a terrible price.

The 20th century had already brought great changes in society and the turmoil of war was to bring extreme changes in Art.

Following the art of Impressionism of the 1870’s and 1880’s, (an early ‘ism’), the door had been opened for artists to experiment and a rush of new forms and styles defied categorisation as artists shared ideas. With a new society embracing change, anything was possible and in art all possibilities were explored. Reviewing these early 20th century developments can be confusing and much like a mad tree branching off in all directions. But if we follow the journey made by the artists rather than the categories imposed by art critics with their ‘isms’, a clearer picture emerges.

These artistic movements all had one thing in common of looking to the future and stepping away from the past.

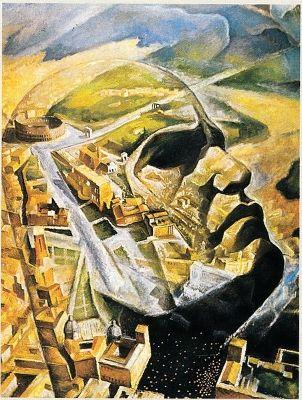

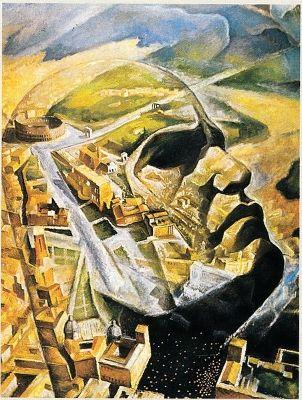

Four Artists and Futurism

In 1909 a challenging article by four Italian artists, was published in Italy and France stating ‘We want no part of the past …. we the young and strong Futurists’. They disparaged anything old and traditional for the new world of speed and technology – the car, the airplane, industrialised society and they were passionate nationalists. They praised originality ‘however daring, however violent’. So as fervent nationalists, they were as much a sociological as an artistic movement, expressing dynamism and energy in an age of new scientific developments. (2) This vision brought four artists together looking for a ‘universal dynamism’ in art with a style to break-up objects and people and then bring these separate objects together. Later to be taken up in the cubism practised by Picasso. They perceived a world in constant movement. Rushing cars, trains, planes and bikes were featured and even found their way into advertising.

Movement was everything

‘Futuristic Motorcycle’, Fortunato Depero, 1914 ‘Unique forms of Continuity in Space’, Boccioni, 1913

With its focus on nationalism, inevitably the Futurist movement was brought into politics and in 1914 they campaigned heavily against the then all-encompassing Austro-Hungarian Empire, heralding Italy’s entry into the First World War in 1915. The realities of war were to bring the group into disrepute and they began to break up.

But in the aftermath of the war, Fascism became the hope of modernising Italy with its industrialised North and archaic South. (‘Fascism’, defined as a far right, authoritarian, ultranationalist, dictatorial society) The futurist style was taken up by the new fascist regime under Mussolini and came to express the new modernist and nationalist vision, leading Italy to join fascist Germany in the next world war.

With Mussolini’s guiding figure

‘Women, Stairs, Skyscrapers’, Fortunato Depero, 1930 ‘Mussolini Aviatore’, Gauro Ambrosi, 1938

However, as Italy’s fortunes later suffered during World War 2, so the vision of a new powerful, all conquering society fell away, and Futurism was consigned to a past that it had earlier rejected.

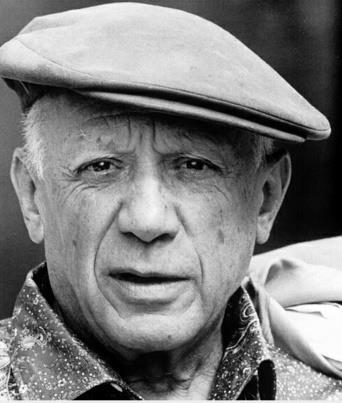

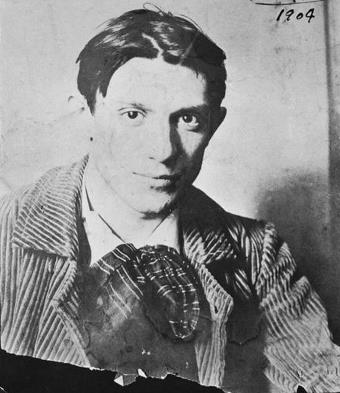

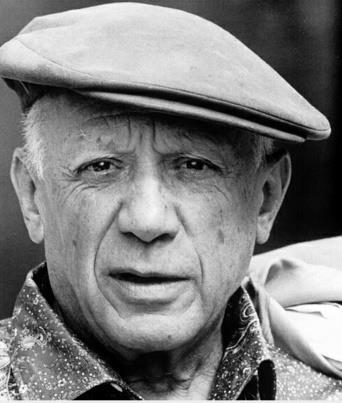

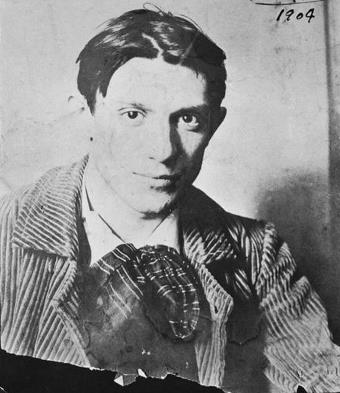

Throughout this time a giant of 20th Century Art – Pablo Ruiz Picasso, 1881-1973 – was developing his style of

‘cubism’, building on the concept practised by Futurists, that was to echo around the world.

Pablo Picasso & Cubism

1908 aged 27 and 1962 aged 81

Pablo Picasso was prominent amongst this ‘new wave’ of art was. Blessed with an extraordinary talent, his mother recalls his first words as ‘piz, piz’ – ‘pencil, pencil’ and encouraged by his father. He was an established traditional painter and lecturing art professor and gave his son a formal academic art training. He very soon recognised that his son’s skill had surpassed him and enrolled Picasso into a School of Fine Arts. But Picasso lacked discipline, skipping classes and instead immersing himself in works such as those by El Greco from the Renaissance with elongated limbs, startling colours and mystical backgrounds. (3) Picasso was developing his own view of ‘modernism’ and in 1900 aged just 19 he made his first trip to Paris, then the art capital of Europe and which became his home for the next 60 years. With no income he lived in extreme poverty and cold, often burning his paintings for warmth, sleeping during the day and working by night.

Picasso’s work had a hard beginning.

His work tended to a gaunt, modernist style and he went through periods where he favoured the colour blue and then the colour rose. Picasso always portrayed a sombre mood, influenced by how he had been traumatised by the death of his sister aged 7 and now by the suicide of a close friend. But his fame was spreading, even to New York where the famous Stein art collectors sought his work. But what route was his work to take?

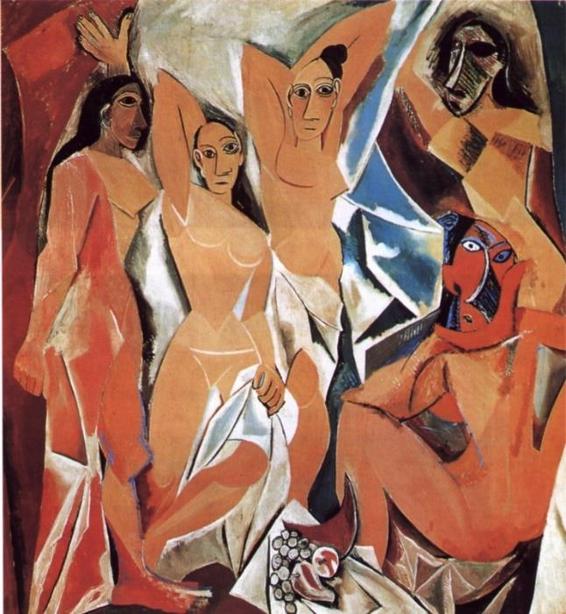

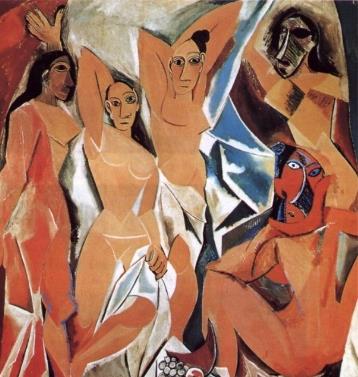

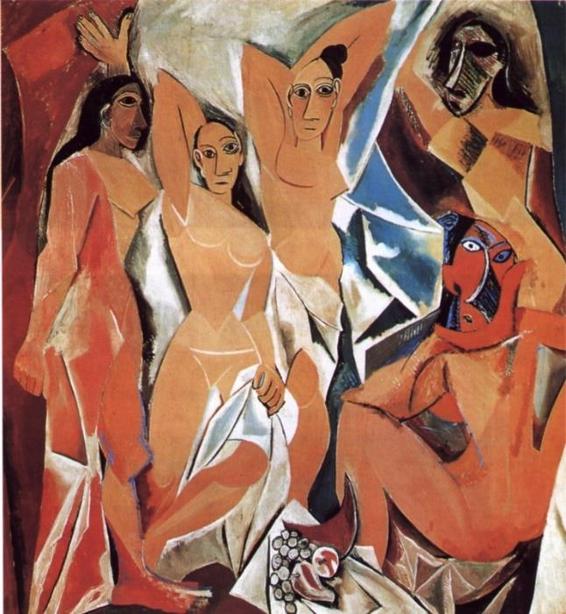

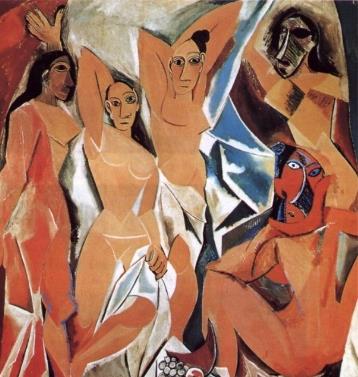

In 1907 he visited an exhibition of African artefacts and was impressed by the long-faced masks, which he then copied and introduced into his painting of prostitutes: Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, the birth of Cubism.

19th century, traditional African ‘Fang’ mask

The poor occupied his mind and prostitutes and beggars became much of his subject matter. His first cubist work was of these prostitutes, leading to the work being described as ‘immoral’. This caused Picasso some doubt and he did not show the painting until 1916, nine years later. In this interval he may have worked on the two heads on the right, which are clearly distinct from the other faces and reflect the African influence.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Pablo Picasso, 1907

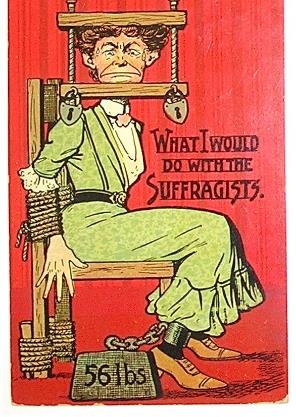

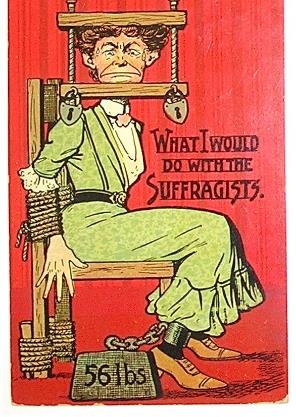

Picasso’s pre-occupation with the lives of women reflected a time when women were campaigning for the vote and greater equality with men. Suffragette (women’s right to vote) protests caused division in society, challenging society’s status quo. Women were arrested, jailed and derided in the popular press. But across the world women came to gain the vote, with society enacting further change in the cries for equality. The world had changed since the 19th century.

In the meantime, he worked with another artist Georges Braque and together they developed a cubist style that took apart objects and reassembled them in a stylised abstracted form, highlighting their shapes in multiple perspectives, as practised by the early ’Futurists’. (4) Girl with a Mandolin, Picasso, 1910 Georges Braque, Little Harbour in Normandy, 1909 The Reservoir, Pablo Picasso, 1909

In the face of criticism, the artists showed their works at the Salon des Independants in Paris, as had the Impressionists before them. Like the Impressionists they had a patron in an art dealer, Daniel-Henry Khanweiler, who guaranteed them an annual income for the exclusive rights to their paintings. The history of modern art may have been very different without these patrons and the doors that they opened.

Around 1920 cubism became less popular, but Picasso was not interested in which school his work could be designated, but only on the effect.

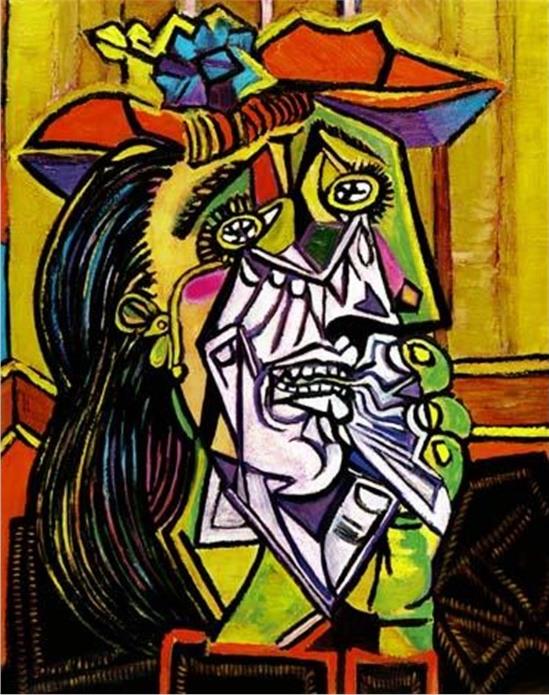

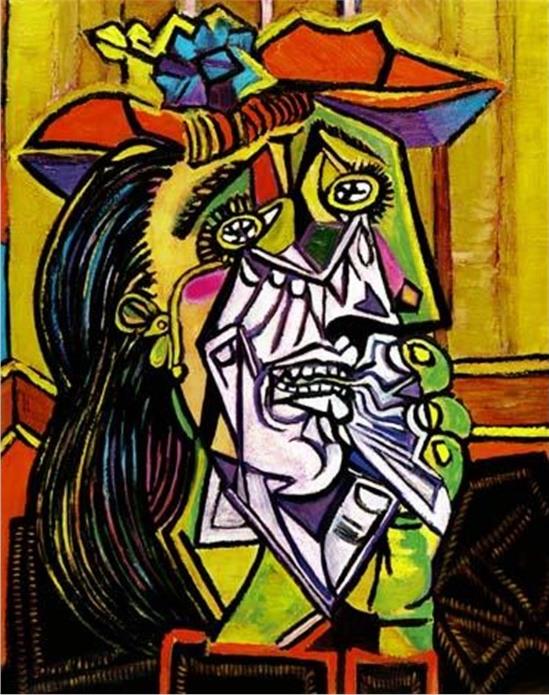

His work became more elaborate and one recurrent theme was ‘The Weeping Woman’. Picasso explained ‘For years I’ve painted her in tortured forms …. just obeying a vision that forced itself upon me. It was the deep reality … women are suffering machines’. An attitude experienced by his muse, Dora Marr.(Book 7) This statement shows how Picasso’s works reflect his emotions, which are then transferred to the viewer. Increasingly art came to portray an emotional experience as in impressionism and cubism, rather than an illustration, as in classical art.

The Weeping Woman, Picasso, 1937

This need and ability to reflect suffering is shown in the piece that could be considered his masterpiece, both in the emotions within the painting and on the events that it portrayed - ‘Guernica’. Spain was in the throes of a Civil War from 1936 to 1939 and Germany stepped in on the nationalist side, led by General Franco. But Germany’s interest was less in supporting their cause as in providing combat experience, primarily for their new air force.

They engaged in bombings of cities and towns, a prequel for later bombings of London and Warsaw. In 1937

they dive-bombed the town of Guernica, causing devastation and loss of civilian life as all the bombs targeted the city centre, to which the civilians had been deliberately herded.

On hearing of this terrible event in his native Spain, Picasso immediately set to creating a momentous canvas 3.5 by 7.8 metres, saying ‘I clearly express my abhorrence of the military caste which has sunk Spain into an ocean of pain and death’. ‘Guernica’ was to go on a tour around the world, including the USA, depicting to everybody the horror of an aerial war. It was Picasso’s comment on the rights of the individual against those who promote war.

Guernica, Pablo Picasso, 1937

Using black and white to add an immediacy, Picasso set out to portray the consequences, not the act itself. The scene is shown within a room forming a basement. On the left, a wide-eyed bull represents Spain and stands over a grieving mother holding a dead child in her arms. A dead soldier with a shattered sword lies under the horse. An awe-struck woman crawls in. On the right a woman raises her arms in terror, trapped by flames(5) After the victory of the Dictator General Franco, the painting was to go on an international tour to raise monies for Spanish refugees, including in New York. Picasso stipulated that the painting should remain there until democracy had returned to Spain. With World War 2 about to sweep over Paris, this was a fortuitous decision.

After the war the work continued to travel to exhibitions around the world and it was not until after Picasso’s death in 1973 and Franco’s in 1975, when democracy was restored, that Guernica returned to Madrid in 1982.

Arguably his pre-war Cubist period was a peak in Picasso’s creativity and thereafter he churned out comparatively ‘hack’ works for the masses. He lived on his fame as the father of cubism where his stamp had been made, influencing avant-garde artists for decades to come.

But across the world to come, many more trials lay ahead.

The Great Depression

War and economic crashes provided much of the scenarios in which artists could find new styles for societies in turmoil. War has its price, not just in human life, but in the aftermath of destruction of both cities and societies.

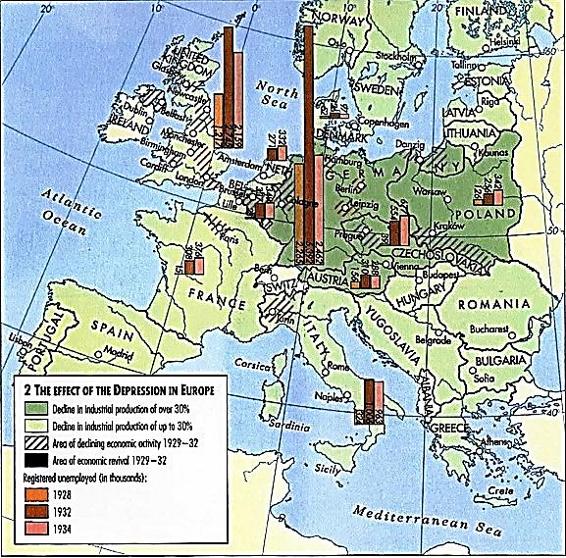

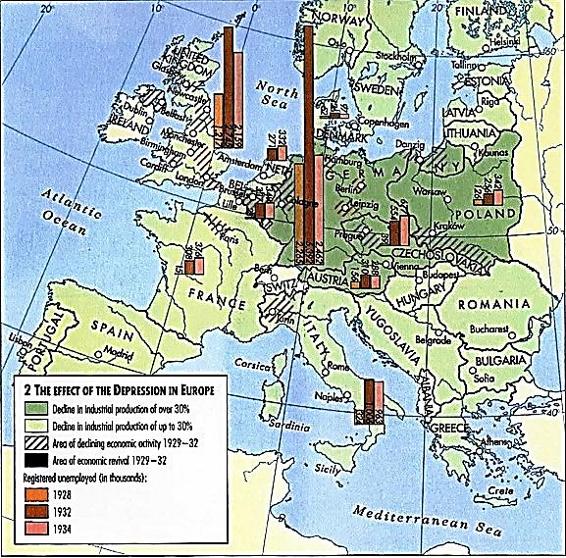

With the disruption and huge costs of restoration after the First World War, Europe and the United States were to fall into an economic depression through the 1930’s. A depression that caused great hardship and unrest with social change, such as under the new undemocratic rule in Spain.

The trigger for the financial collapse came first in America where the over heated stock market collapsed in 1929, followed by a decade of great suffering. Industrial output collapsed by up to 40%. Unemployment soared to 25% and the whole system caved in on itself. (6) (& Book 5)

Central Europe was hit hardest as the industrial driver Germany, crushed by defeat in the war, totally collapsed.

In Europe anger spread between countries. With

Germany losing the war, they were saddled with

enormous financial reparations. As their economy

stuttered, they were unable to meet these debts,

which France protested they depended upon.

International trade collapsed, there was a rush to

withdraw gold deposits from national banks, bank

lending dried up. Money was no longer available.

The impact was sudden and severe. Economic

activity shrunk.

Central Europe was worst hit and in Germany

blame was laid against the rest of Europe

demanding these huge debts, although they were

to pay very little before the next war. The social

cost led to a call to nationalism and to the rise of

the fascism of Hitler and the Nazis. In Italy

nationalism gave rise to the fascism of Mussolini

and with France and Great Britain still weakened

by the war, there was no appetite to challenge

these new forces.

The path of the Depression in Europe

Across the world, people marched in the streets and a popular uprising and revolution became a real fear, as had happened in Russia in 1917. Governments were caught between trying to contain the economic catastrophe with the need to respond to the suffering and despair unfolding outside of their doors.

Bread lines formed, people marched for jobs

and industry cried out for investment, but with

no markets to trade in. The USA launched a

‘New Deal’ to invest vast public monies in

infrastructure, such as dams. Slowly confidence

and money returned to restore consumer

spending and trade, but family incomes had

suffered. Families struggled and wives had to

look for part time jobs, further impacting the

unemployed men of the family. Wages fell,

family budgets fell and food became

unaffordable, causing ‘hunger marches’.

Public protest in London 1932, prior to a General Strike

Economies remained depressed with little and slow recoveries, until nations began to prepare for war. Germany was first to rearm its forces, on land, sea and air, using government borrowing to fuel the investment, boosting employment and wages. Germany was experiencing good times again and under Fascism and Hitler, with the Nazi party, promoted national superiority and strength in recovering their power to conquer Europe. A similar picture appeared in Italy with an alliance with Germany. Finally, France and England woke to the dangers and began to invest, boosting employment. Poland with a small army was most vulnerable and France and England agreed to come to their aid if Germany invaded. Germany did invade and France and England declared war.

Ironically it was war that destroyed economies and it was to be war that would revive these same economies.

The people of Europe had war visited upon them again, just 20 years after the First World War that was termed

‘The war to end all wars’.

This almost surreal environment was expressed in a new artistic style that questioned reality.

Salvador Dali & Surrealism

Appearing internationally in 1936, Surrealism was to provide an outlet from the destruction of World Wars, that responded to the post war society’s question as to ‘What does it all mean?’

One of the most recognisable exponents of surrealism was Salvador Dali, (1904-1989) whose dreamlike works and magical worlds can lead us out of the material world that we inhabit. Dali’s obsession with other worldly states was sown early in his life when his parents took him to his brother’s grave and told him that he was his brother’s reincarnation. Dali came to believe this saying ‘we resembled each other like two drops of water … he was probably the first version of myself’.

Like Picasso, Dali was born and studied art in Spain where he became interested in ‘cubism’, but leaving before completing his final exams. He also moved to Paris, grew his famous flamboyant moustache and became involved with ‘surrealism’, first in film and then in painting. Here he met Picasso whom the young Dali revered and Dali made a number of works strongly influenced by Picasso’s cubism. Over the next few years Dali would develop his own style outside of the box of everyday life. His most famous work depicted the looseness of time that we experience in dreams and drew on Freud’s psychoanalysis of the sub-conscious mind. (7) The work imagines a dream world where time

slips away when we dream, unlike the rigid time

when we are awake that determines all. Dali

provides a soft image of melting pocket

watches, some being devoured by ants as a

symbol of decay in time. In the middle is a

sleeping creature that cannot be defined, much

as in our recollections of dreams. The strange

dreamlike quality of surrealism.

The landscape is an image of his home in

Catalonia with the brooding shadow of

mountains.

The Persistence of Memory, Salvador Dali, 1931

Dali married Gala, a Russian immigrant who acted as his business manager steering a path through looming insolvency from their extravagant lifestyle. Society looked up when Dali held an exhibition in New York in 1934, creating an immediate sensation. The exhibition was as much of Dali as to any display. He swished around in a gold cloak of dead bees, releasing boxes of flies. Dali and Gala then paraded at balls and parties, projecting an eccentric and artistic image. Dali had become a brand. At a subsequent exhibition in London, Dali arrived in a deep-sea diving suit with a pair of Russian wolfhounds, before being rescued from suffocation inside the diver’s helmet. His eccentric image and reputation were established and his works and exhibitions would always draw comment. Again, a patron emerged in the form of wealthy Edward James in London, who bought many of his works, staving off bankruptcy.

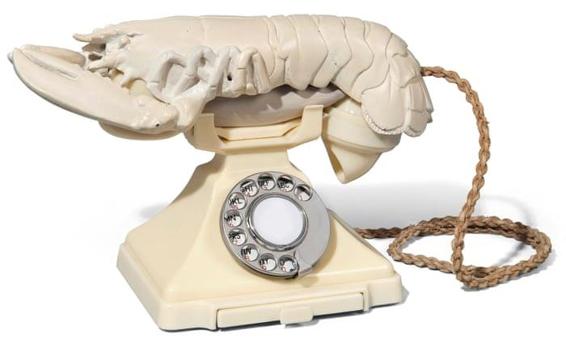

His creativity would now extend into everyday objects, modified and extended into other realms.

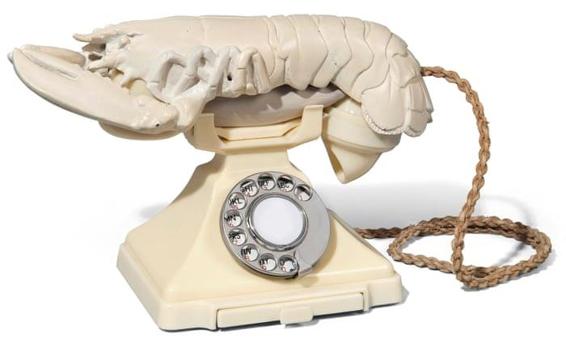

The Lobster Telephone, 1936 Mae West Lips Sofa, commissioned by Edward James, 1938

Undoubtedly these would open other paths for new artistic presentations utilising every day objects and for new forms of ‘modern art’, not seen before. They ranged from Jason Pollock’s drip painting in arcs and loops (8) to David Hockney’s geometric paintings. (9) New art galleries seized on these entertaining works and prospered.

Dali moved to the USA during the war and diverted into design across a range of jewellery, clothes, ballet and even shop windows. In his later years his creativity would continue with a varied range of approaches often involving optical illusions, being the first artist to use holography. Dali was distraught when his wife Gala died in 1982, attempting to place himself in a state of suspended animation. Finally, his heart was to give way and he died in 1989. Dali left an enduring legacy through his unique contribution to world of art. His last statement read

‘When you are a genius, you do not have the right to die, because you are necessary for the progress of humanity’.

Salvador Dali became a cultural icon and many of today’s modern artists attribute the inspiration for their creative ideas, to him.

Warhol, Emin & Dadaism

Inspiration from earlier artists can travel across decades as artists look for new expressions. Andy Warhol in the 1950’s and Tracey Emin in the 1990’s, owe much to a Parisian escaping the First World War - Marcel Duchamp.

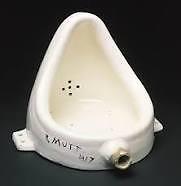

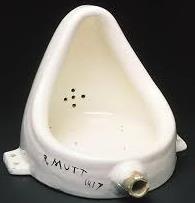

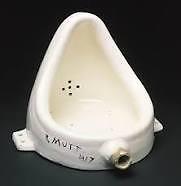

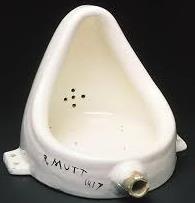

It all started with a toilet fixed to a wall.

An early cubist, Marcel Duchamp left Paris during the first World War and set up in New York. To establish himself he controversially submitted a toilet (urinal) to a major exhibition of modern art.

A standard off-the-shelf item, Duchamp gave it the name of the manufacturer, changing ‘Mott’ to ‘Mutt’, drawn from the comic strip ‘Mutt and Jeff’. Under the title of a new art, the exhibition was shown in Zurich and New York where the organisers were committed to not refusing any work, but hid this work from direct public view.

This event introduced ‘Dadaism’ to the world – a title possibly captured from an infant’s ‘dada’ for ‘daddy’. A movement formed against the bourgeoisie forces that drove the destruction of the First World war. With a manifesto to be ‘anti-art’, rejecting traditional forms that they saw as part of a culture that can lead nations to war. They rejected ‘reason and logic’ that had created treaties leading to the war and instead stood for ‘nonsense and intuition’ to provoke reaction and discussion.

‘Fountain’, Marcel Duchamp, 1917

Duchamp’s contribution was placing this mass manufactured ‘ready-made’ object, at the heart of the art institutions and to do that in an America that had just joined the conflict in Europe. The people of the USA were also led to a ‘European’ war that they had no part in and also questioned ‘reason and logic’.

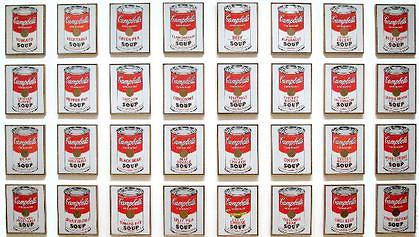

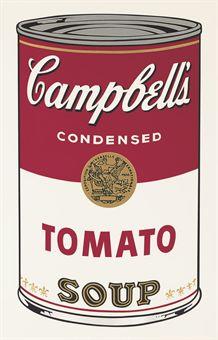

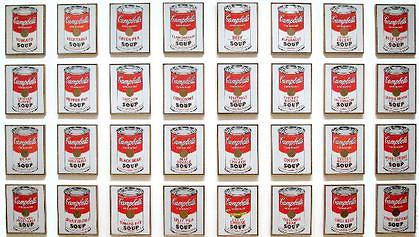

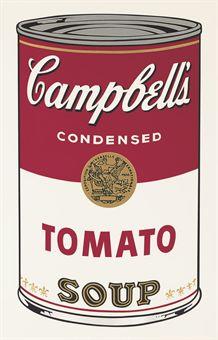

Stirring up media interest with this provocative display, Duchamp’s urinal is surprisingly seen as one of the most influential artworks of the 20th century and the precursor to a myriad of future displays. As the dust settled from the second World War, optimism swept America and its un-bombed and mightier industry exported to a war-ravaged world and fuelled a consumer boom. Art could now do anything, such as the repetitive painting of Campbells Soup Cans by Andy Warhol in 1962 and Tracy Emin’s installation ‘My Bed’ from 1999. As with Duchamp, they both presented an object outside of artistic endeavour, with an item solely elevated by its surroundings and influenced only by the artists’ choice. (10)

‘Campbell’s Soup Cans’, Andy Warhol, 1962 ‘My Bed’, Tracey Emin, 1999

Comprising 32 varieties of Campbell’s soups on individual canvases and produced by a team in what Warhol termed – ‘the factory’, each canvas was made by a semi-mechanised screen-printing process using a photograph for a stencil drawing that could be easily replicated. This came to be termed ‘pop art’ and this ‘non-painterly’ style quickly drew criticism which – as so often with new art – established Warhol’s reputation. As to why Warhol chose these everyday objects that he had bought from a local supermarket, he said ‘I used to drink it, I used to have the same lunch every day for twenty years’. The question becomes ‘why not?’

Tracey Emin had much the same motivation when for the Turner Prize, she presented her own bed that she had slept in for two weeks, redolent with body stains and objects such as a slipper and underwear. When also faced with critics claiming it a farce that no-one had done before, she replied ‘Well they didn’t, did they? No-one had ever done that before’. Another case of ‘why not?’

Tracey Emin did not win a prize, but also gained notoriety and ‘installation art’ came to fill the outbreak of new art galleries needing something to fill their vast spaces in a need to entertain and attract visitors. The 20th Century regarded art much more for its attraction and entertainment in a fast-moving consumer society, than for the pure aesthetic values of the past. Society called upon art to portray their ever-advancing technological world, in a search for a new culture. The simplicity of contemporary art is better suited to both offices and the new minimal domestic interiors in comparison with ‘heavier’ classical works.

In these developments the term ‘art’ has expanded to embrace any installation or object intended to entertain, with a defining line between ‘Classical’ and ‘Modern’ art, with displays of the present termed ‘Contemporary’.

Art by its very nature will always evolve as society evolves, as it has done over the centuries.

The start and the finish?

Summary

Four Italian artists introduced a new form of art that rejected the old and the past and expressed the new Italian industrialised society with energetic images of power and speed, in Futurism. They came to be inevitably politicised in the new Fascist regime that was to lead Italy into a disastrous war alongside Fascist Germany.

Then alongside this Picasso came to introduce Cubism which was to dominate art for decades to come. The essence was of breaking up an image and reassembling it in an abstract, yet harmonious form. His work was driven by emotion, initially on the lives of women, with one famous work showing a ‘weeping woman’

These emotions and concerns led to his masterpiece ‘Guernica’ depicting the suffering of townspeople during a bombing by German planes in the Spanish Civil War. A work that was to tour the globe and became a symbol of the suffering of war, not returning to Spain until the Fascist dictatorship of General Franco was finally removed.

The Great Depression that followed the First World War, threw the Western world into great poverty and suffering. Millions of men and women were thrown out of work as money, then trade, then industry all collapsed. Economies that were not to fully recover until the Second World War, when national states borrowed to finance the materials of the next war.

The economic suffering and the deaths of the Second World War, heralded the growth of Surrealism that sought to express the unconscious or dreamlike mind described by Freud.

The style gained status largely by being championed by the master of self promotion, Salvador Dali. His creativity would extend to a sub-conscious representation of everyday objects that would encourage future developments and presentations.

Artistic expression moved on from artistic works to the use of ‘readymade’ objects that started in 1917 with a toilet screwed to the wall under Dadaism. This would be taken up by

‘Pop Art’ and ‘Installation Art’ in an expression that splits opinion today.

The evolution of art and societies.

Sources of information

(1)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Causes_of_World_War_I

(2)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Futurism

(3)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/El_Greco

(4)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cubism

(5)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guernica_(Picasso)

(6)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Depression_in_Central_Europe

(7)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salvador_Dal%C3%AD

(8)

https://www.jackson-pollock.org/

(9)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Hockney

(10) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andy_Warhol & https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tracey_Emin

A BBC series ‘Civilisation’, provides a history of art and society from the middle ages to the present day, over 13 episodes

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLXC6RzjHc2wugLza1kMWN_CRBuKRqQNTw

The history of life and art

across centuries of

changing societies and

changing cultures.

‘I think the concept for your work is both creative and engaging for young people.

The links between art, history, society are clear in the outline you provide and the opportunities to stimulate young people’s interest and imagination are evident’.

Sir Nicholas Serota,

Chairman, Arts Council, England

Society makes art and art defines society’s culture