ARTY

STORIES

Book 5

THE AMERICAN DREAM

Depression to Optimism

Art and life

across the centuries

Ian Matsuda, FCA, BA (Hons)

for

Noko

Copyright

Ian Matsuda, FCA, BA (Hons), 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, transmitted or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher or licence holder Website: artystories.com email: history@artystories.com

A Dash for the Timber’, Frederic Remington, 1889

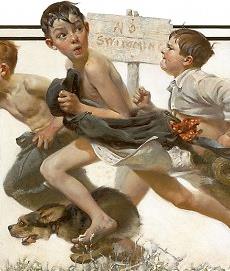

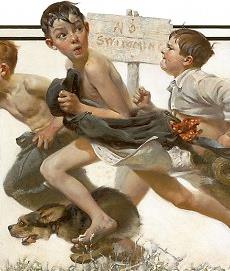

‘No Swimming’, Saturday Evening Post cover, Norman Rockwell, 1921

‘ARTY STORIES’

Art & Life across the centuries

‘Seeing people’s lives brings their art to life’

See the stories that made the art – the times – the place – the people Book 5: THE AMERICAN DREAM – Depression to Optimism

A refreshingly entertaining introduction to the world of art through 5,000 years of tumultuous history This fifth book describes a new world that endured great struggles on the road to the birth of a new nation.

America ripped itself apart as generation of young men killed each other in the cotton fields of the South in a Civil war against slavery. But new adventures were to follow in the new lands of the west, only to be dashed by the Great Depression that destroyed lives and families in the dust bowls of that west. An American culture of self-reliance emerged as a great democracy and the new America was to bring leadership, a moral compass and entertainment, to the world.

Ideal for student and art lover alike

Supported by the Arts Council, England as:

‘creative and engaging for young people’

‘the opportunities to stimulate interest and imagination are evident.’

Centuries of great art are a gift to us all

Books in this Series

Book 1 Pre-History & Greece to Rome Olympics & Empires 2 The Renaissance in Italy The Patron & The Artist 3 The Four Princes War, Terror & Religion 4 Northern Europe Revolution & Evolution 5 The American Dream Depression to Optimism 6 The Modern World The ‘..isms’ of Art 7 Past Voices Stories behind the Art All free e-book downloads

https:/www.artystories.org

Book 5

THE AMERICAN DREAM

From depression to optimism

CONTENTS

• The Civil War

• The Great American West

• The 20th Century

• The Great Depression

• Steps into optimism

• A post-war boom

• Summary

• Sources of information

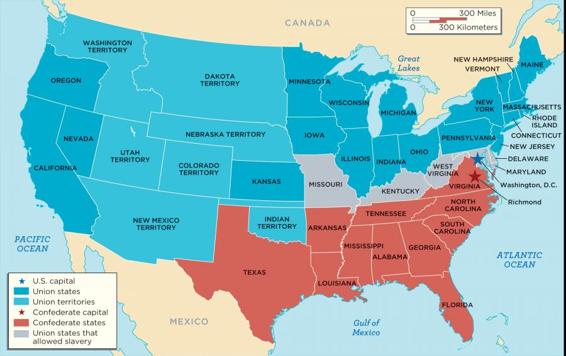

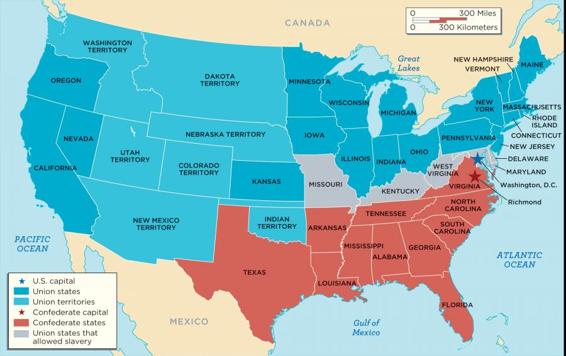

The Civil War

The first settlers came to America some 400 years ago in 1607, escaping religious persecution and looking to find a new world – a new utopia, the American Dream. They came to build new colonies for their native countries and it was to be a further 170 years before they gained independence from Great Britain in 1783.

But 80 years later; as new states

were formed; differences began to

emerge, primarily on the enslavement

of black slaves from Africa who toiled

in the southern lucrative fields of

cotton and tobacco. In 1861 eleven

southern states out of the 34 formed,

seceded from the country to form the

Confederate States and set the

ground for the American Civil War.

The question of black slavery was

such that in 1862 President Lincoln

proposed to a Committee of coloured

leaders that ‘It is better for us both to be

separated’, suggesting that they

emigrate to Central America.

Both sides immediately introduced conscription, raising armies from civilians and setting the North-South divide. The

Confederate armies gained the early victories, destroying larger Northern ‘Union’ armies. But the Southern Confederacy lacked the resources of the North and the tide began to turn with the Union General, Ulysses Grant engineering gains in the west. At the bloody battle of Gettysburg in 1863 General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate army was defeated and the South fell into retreat.

Across both sides, casualties in the field totalled 50,000 men.

Surgeons were to be avoided with a reputation for incompetence and laziness. The North had virtually no medical facilities at the outset and at the earlier Battle of Bull Run in 1861, 3,000

wounded still lay injured in the field 3 days after the battle. (1) Battle of Antietam, 1862, Library of Congress

As the Union armies battled south, they set out to destroy what resources the Confederates still held, setting fire to homes and fields, ravaging the countryside and towns and cities. Hungry women in the towns protested in ‘bread riots’ and in Richmond 5,000 broke into shops to steal provisions. The army were called in to restore order, but resistance to the war was mounting as the suffering increased.

As the Union armies swept down the Mississippi river, they cut the Confederate army in two. Depleted by the mounting casualties and deserting conscripts, Lee had a smaller army to confront the well equipped Northern Union and defeat was inevitable.

Finally, at the Confederate’s last stand at the capital of Richmond, Virginia, Lee was surrounded with the city in ruins and he finally surrendered to a corps of black troops, in humiliation.

Four years of intense and bloody battles had left up to 700,000 people dead. More than the total losses from the four 20th century wars, (World wars 1 & 2, Korea and Vietnam) The South was devastated with political power now in the North, but in a divided country.

This was the first war to be recorded by camera and the immediacy and unvarnished dreadful truth was depicted in 7,000 photos. The immediacy and stark truth of these photos, brought the war into every home.

Richmond Virginia, 1865. Final days of the Confederacy,

‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’, 1969 ballad

The savagery of the young men of America killing each other hit Americans hard, as if their New World had been lost. Many Southern plantation owners lost their land with devastated cotton and tobacco farms. They now had a worthless Confederate currency and the new crippling land taxes, drove these ‘Southern Gentlemen’ into bankruptcy.

Northerners (termed ‘carpetbaggers’) seized the opportunity to purchase these farms. Whilst they provoked great resentment, they restored the plantations, employed both white and black ex-slaves and established schools and banking systems. In short, resentment was to turn to relief as the country looked to a slow reunification and rebuilding. The deep depression of war recovered some optimism and although America had lost its innocence, it was eventually to emerge stronger and become truly ‘The United States of America’.

From these losses people looked to the new lands of the west and a drive west grew. Landscapes of a vast unspoilt and beautiful wilderness fed the vision of a wonderful new country waiting with a new history.

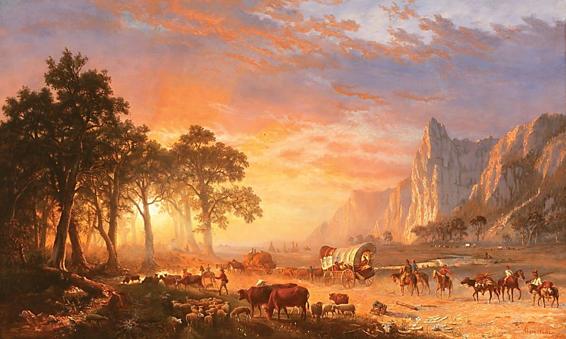

The Great American West

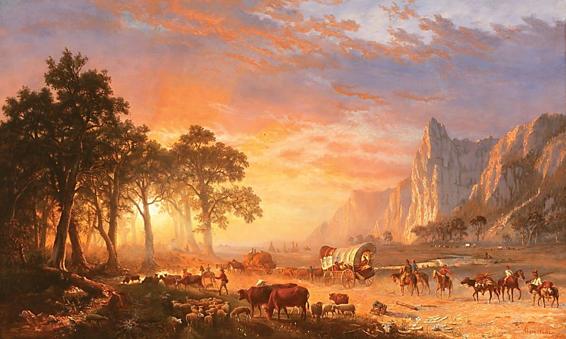

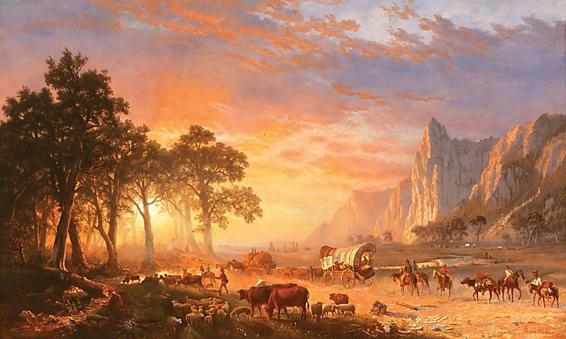

A country free of war again looked to the untapped riches of the West and landscape painting was to encourage the westward expansion. One famous wagon trail opening these new lands, was the ‘Oregon Trail’ – a 2,170 mile trek, over mountains and across plains to the Pacific.

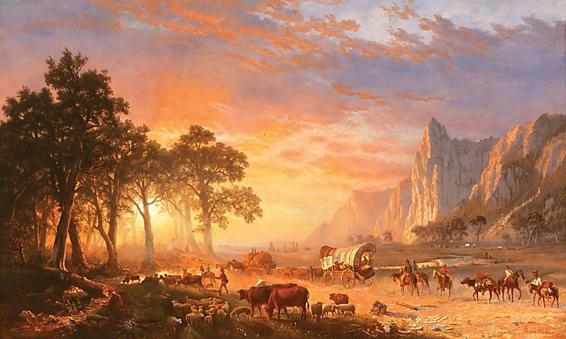

One artist Albert

Bierstadt portrayed a

sense of majesty and

divine beauty, drawn

from his homeland in

Germany and the

romance of their art.

His immense luminous

canvases were inspired

by his early travels along

the wagon trail. A master

of self- promotion, he

held exhibitions across

Europe. He glorified the

American West as a land

of promise, and is

credited with ‘fuelling

European emigration’

(2)

‘The Oregon Trail’, Albert Bierstadt, 1869

Another artist to celebrate the great outdoors was Winslow Homer who also rose from magazine illustrator at Harpers Weekly, to world renowned artist. In this respect the media acted in supporting artists, like the art patrons of old.

Homer’s love of outdoor ‘pursuits’ embraced

mountain, but he is best known for his

seascapes that capture the ‘Wild Coast of Maine’

and children riding the waves in a new spirit of

freedom.

Through the magazines his paintings reached

the masses, celebrating the national ownership

of America’s exceptional beauty, instilling a

shared bond across society, promoting:

‘America the beautiful’.

Breezing Up, (A Fair Wind), 1874, Winslow Homer

But the lure of the West still held appeal and one artist typified these iconic images, Frederic Remington, for whom the cowboy was his focus saying ‘With me cowboys are what gems and porcelain are to others’. A restless individual, Remington was not suited to the academia of Yale University and instead took his inheritance monies west where he invested in cattle, mining and finally a saloon. As his money dwindled, he began to sell his sketches and also became an artist-correspondent for Harpers Weekly, specialising on the Apache leader Geronimo. Although he never caught up with Geronimo, his artistic prowess grew and his work appeared in the front cover in 1886.

Remington ventured west to

experience the Apache wars and

from his brief and unsuccessful

attempt at ranching, became the

authentic ‘pseudo cowboy’, at a time

when the early West was inevitably

disappearing. He preferred ‘action’

works and here we see the iconic

cowboys fighting off a chase from

Apaches. He went on to produce

2,700 paintings. The excitement,

speed and adventure sweep out

towards a viewer

A Dash for the Timber’, Frederic Remington, 1889

These ‘heroes’ masked the true cost of the adventure west, which had terrible consequences.

To most Americans the Indians were considered a threat to be overcome and the land to be ‘settled’. These ‘new Americans’ looked to conquer this vast continent, often at the expense of the estimated 5-15 million Native Indians who had lived there for thousands of years before the arrival of any settlers. The continent was not to be shared, but to have new owners, more powerful than the indigenous tribes. These Native Americans endured epidemics of diseases brought from Europe with measles and smallpox decimating 90%. Then war and forced relocation as the US Government sought to destroy their culture, religion, and way of life. (3) Akin to a genocide, the European settlers replaced the Native Indians and by 1900 just 250,000 remained and just 500 of the 60 million buffalo. Their tragic history up to the final massacre, is set out in the book: ‘Bury my heart at Wounded Knee’ by Dee Brown. (4) America was moving towards the 20th Century and a new society was building in the new cities.

The 20th Century

As the world opened up, artists travelled to Europe and Paris, seen as the cultural centre of art.

There they found impressionism that had first come to New York in 1885. (Book 4).

An early advocate was Mary Cassatt who became a friend of Degas and the only American to have her work exhibited alongside the Impressionists in 1891. An unusual achievement in those unliberated times. Her subjects were domestic scenes mostly of women as she did not enjoy the outdoor artistic freedom of her male counterparts.

Mary Cassatt, 1844-1926

Mary strongly criticised the Parisian Art Establishment and when her works were refused display in their Salon, she found a common cause with the similarly refused Impressionists, joining their exhibitions. (Book 4) Japanese art was currently attracting interest in Paris as in the oriental carpet, wall hangings, chest of drawers and water pitcher in this domestic scene of a mother tenderly washing her daughter’s feet, with the absolute concentration of them both, seen from above as if by someone were entering the room.

Mary made her home in France, but her work was exhibited in America and she did much to encourage American art dealers to buy Impressionist works, that had found so much favour after their earlier introduction in 1885. (Book 4)

‘The Child’s Bath’, Mary Cassatt, 1893

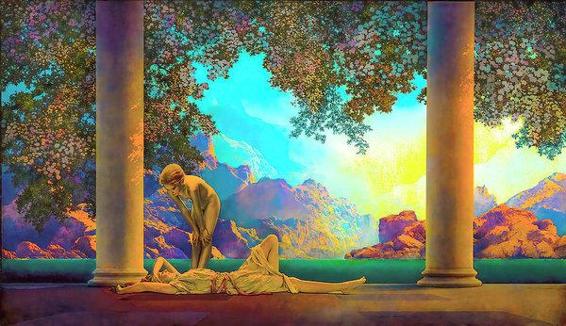

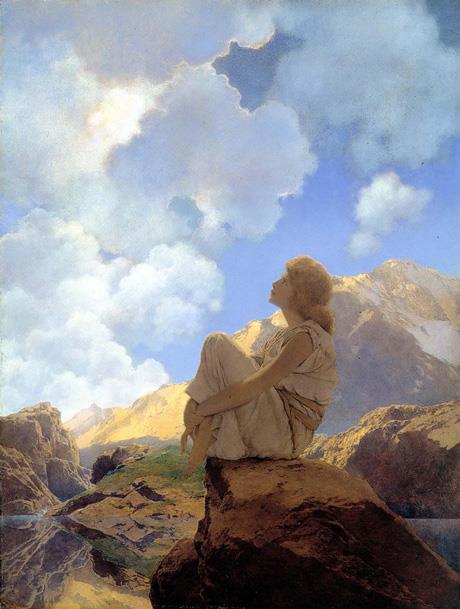

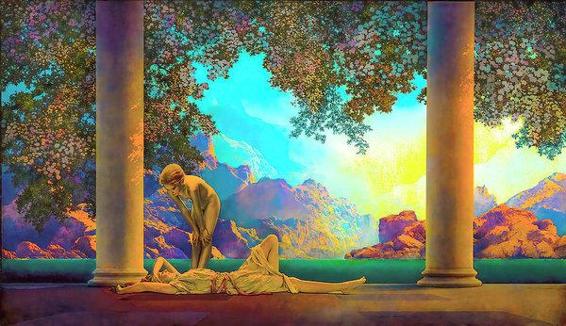

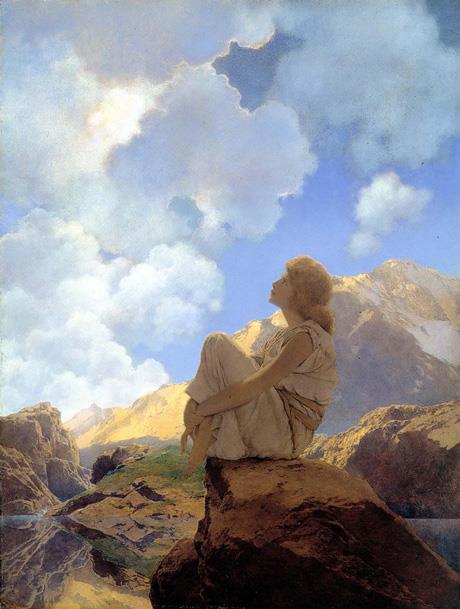

At the same time another ‘illustrator’, Maxfield Parrish, was realising great success with vibrant paintings incorporating classical themes, which were popular in the Art Nouveau fashion between 1890-1910. Starting with illustrations for children’s books, he went on to design a cover for Harpers Weekly and became particularly popular for his annual calendars, which became collectors’ items, with some selling more than 200,000 copies.

Parrish had a very precise technique, applying layer after layer of thin oil paint to the paper, with coats of varnish in between. The effect was highly detailed, producing luminous pictures, with his popular skies being termed ‘Parrish blue’.

The whimsical nature of his work chimed with the social themes of the time in the sinuous curves of Art Nouveau and the imagined settings. These also reflected the current fascination with a spiritual life, conjured up in his works.

‘Morning Spring’, Maxfield Parrish, 1922 ‘Daybreak’, Maxfield Parrish, 1922 (200,000 prints)

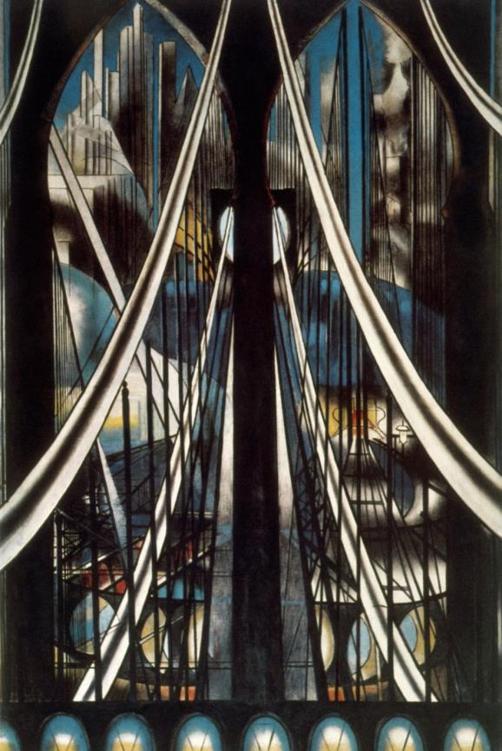

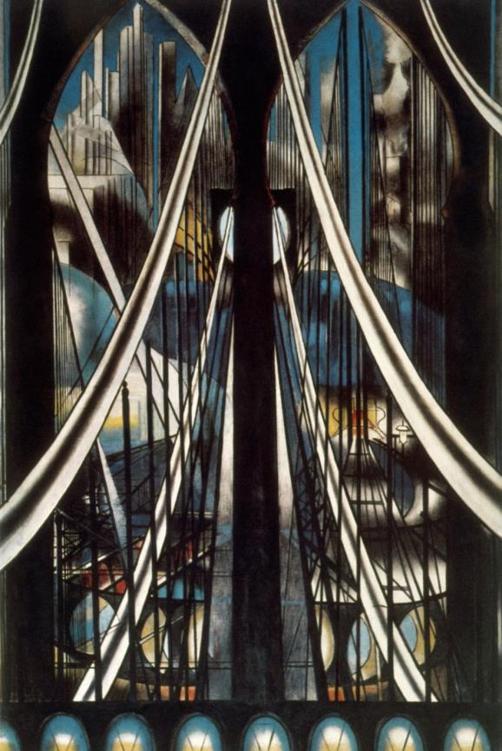

By the start of the 20th Century this pre-war art nouveau interior and architectural style, was to be superseded by the new art deco. An Italian immigrant Joseph Stella was fascinated by the geometric quality of the architecture springing up in 1920’s New York.

Here he captures the soaring spirit of America in the strength of the supporting cables of a new bridge sweeping up and imitating the skyscrapers in the background. The bridge was a new feature further connecting the island of Manhattan to the mainland, displaying the energy and pace of modern life.

Skyscrapers were themselves becoming

artistic structures in their own right,

reflecting the Art Deco fashion of the time.

The architecture brought a romantic

theme to the city, to provide an image of

New York as a city to rival Paris. Art Deco

followed the earlier decorative style of Art

Nouveau and was a grander, more

opulent design that caught the spirit of

invincibility at the end of the First World

War.

A new vibrant society and culture was

emerging. An aspiration soon to die.

Joseph Stella, Brooklyn Bridge, 1919-20

New York, Chrysler Building, Art Deco style, 1930

The 20th Century was to herald rapidly increasing immigration bringing a cocktail of cultures. America needed to redefine itself, but it would take a further war and economic collapse before a proud and optimistic America would again emerge. The First World War of 1914-18 and the ensuing worldwide economic depression waited around the corner and a new American ‘realism’ caught the agony.

The Great Depression

The depression in the USA came from an over-optimistic and over-heated economy, with excessive corporate speculation matched by consumer debt that was often used for stock market speculation. A viscous spiral, shattering American’s faith in the future. As people rushed to withdraw their savings, money dried up and confidence was lost, instigating a sharp decline in manufacturing and agricultural production. The economic boom of the 1920’s was to lead to a sudden and steep fall into recession and in 1929 the Wall Street stock market collapsed, losing 90% of its value, bringing down the ‘whole pack of cards’. Bankruptcies, suicides and destitution followed with unemployment of 25%. In the mid-west an agriculture that had boomed during the good times of World War 1 army contracts, now saw crop failures. With no crops to hold the soil, farms fell into ‘dust bowls’ where topsoil blew away and nothing grew.

The ‘dust bowls’ blew into people’s lungs and suffering was widespread with 60% of rural families classified as ‘impoverished’. Unemployment and falling wages drove many into homelessness, living in cardboard ‘shacks’ where a lack of sanitation resulted in disease and illness. Farm prices fell and as they were then hit in 1931 by one of the worst droughts in history, farmers lost their farms.

One child later said ‘You get used to hunger. After a while it doesn’t hurt, you just get weak’. Family members swapped clothes, each taking turns to go to church in the one dress they owned. (5) One child told by her teacher to go home and get food said ‘I can’t. It’s my sister’s turn to eat’.

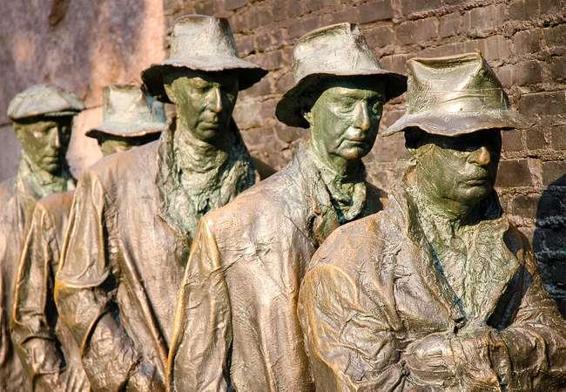

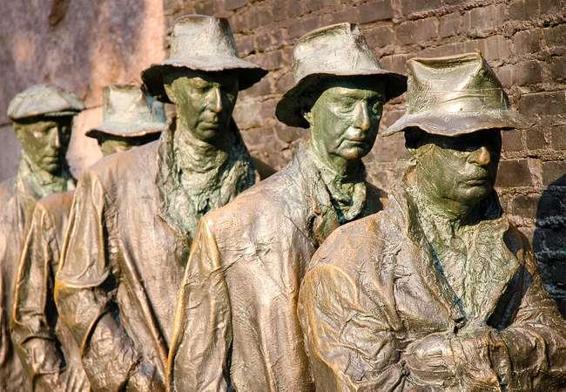

Bread lines and soup kitchens were a common sight,

serving 85,000 people daily in New York alone, as

remembered in this bronze sculpture.

The end only came with a new President in Franklin D.

Roosevelt (FDR) in 1933, who introduced the ‘New

Deal’ as he delivered a massive injection of public

monies to invest in infrastructure with dams and roads

kickstarting employment and the moribund economy,

supporting farmers and regulating banks. This

programme ran to 1936 and restored much of

consumer confidence and although not immediately

restoring jobs long term, realised a spirit of optimism.

‘The Bread Line’, George Segal, 1991, FDR Memorial Washington DC

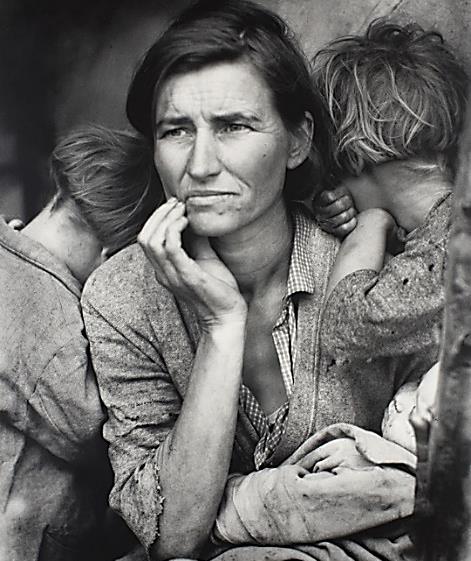

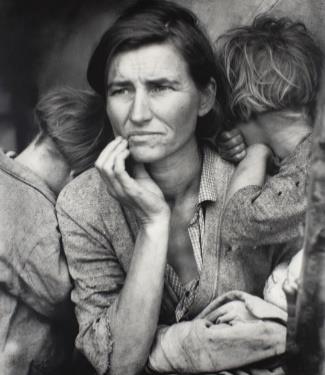

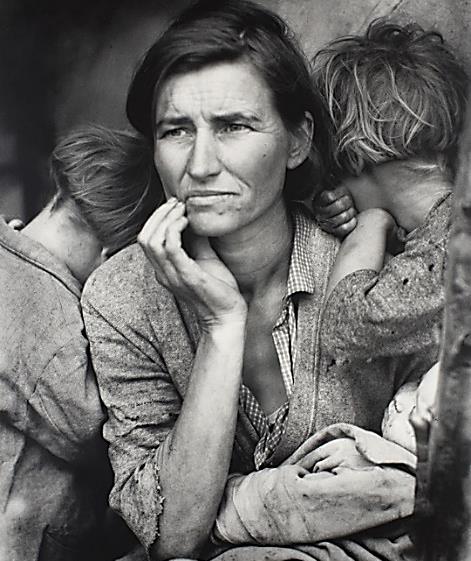

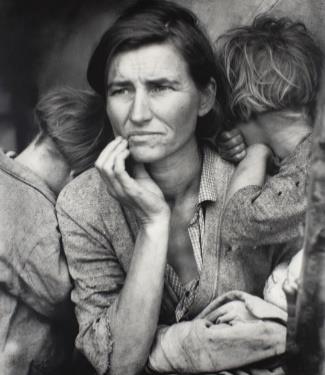

The depression brought a cultural reflection on the importance of family life and concern for the community as a whole. This famous photo holds the gaze of the woman beaten into despair, looking out with nowhere to look, while her family seek protection around her. But a US culture of self-reliance came to be born. A respect for the self-made man ran through society as the Depression ironically forged the foundation of modern America. This was to reach its nadir in the Second World War, when American armies swept enemies aside and then helped restore their battered economies in democratic societies. The US held a moral and economic standing that would provide a worldwide power and influence for the next 50 years.

‘Migrant Mother’, Dorothy Lange, 1936, (Florence Owens-Thompson, aged 32)

Movies reflected this cultural shift providing an escapism to better times and Hollywood entered its golden era, with an image to the world of a vibrant, successful life in distinct contrast to the hard times experienced in Europe.

Steps into Optimism

The decade started with songs such as ‘Brother can you spare a dime’, but recognising peoples’ ambitions for happier times, films moved to musicals and glamourous sets where songs such as ‘We’re in the money’ & ‘Happy Days are Here Again’, became popular. People wanted to forget their worries and Hollywood became the entertainment centre of not just America, but of the World.

Cinemagoers were happy to pay a precious 25 cents to see

the madcap escapades of the Marx Brothers or the dazzling

dances of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. The 1930’s were

to end with the musical ‘The Wizard of Oz’ where ‘good’

overcomes ‘bad’. Followed by the community tear jerker ‘it’s a Wonderful Life’, where a family business owner succeeds

against an unscrupulous banker, the scourge of the

Depression, but now firmly in the past.

The Arts again reflected life and were again to shape not only the national culture, but the national mood. The vision and morals of Americans were to guard their democracy and the

freedoms that all men should enjoy.

Original Movie Poster from 1939

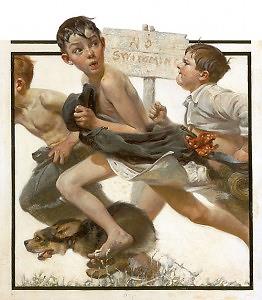

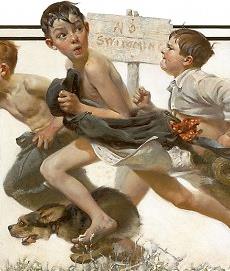

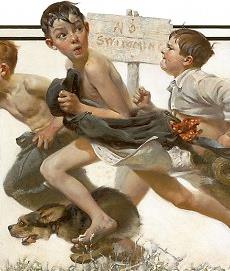

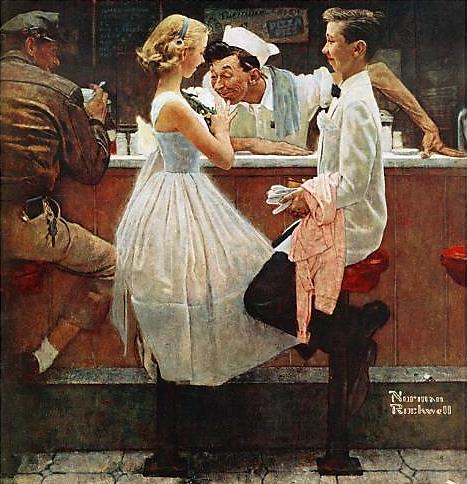

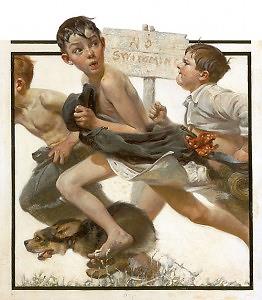

It was not just the movies that would contribute to this reawakening, but the ever-popular magazines that entertained and informed. Prominent amongst these was ‘The Saturday Evening Post’ where it’s cover page artist Norman Rockwell, gained popular appeal with his endearing images of family and community life. (6) Picasso said that ‘The purpose art is washing the daily dust of life off our souls’ and for five decades Norman Rockwell did just that, providing faith and reassurance to millions

through a world war, the great depression, the Korean

and the civil rights struggles, steadily providing a window into a more idyllic world.

Imbuing his work with a sense of humour and natural

playfulness, his characters often displayed a wry smile.

He portrayed a world in which all would want to belong

and helped induce a bond between Americans in a

country both still new and still experiencing ‘growing

pains. This was a life that all could relate to and was as

American as ‘apple pie’.

‘No Swimming’, Saturday Evening Post cover, Norman Rockwell, 1921

Norman Rockwell was probably the world’s most prolific

painter producing over 4,000 works from 1916 to 1978. His

‘sentimentalised portrayals’ were largely dismissed by

serious art critics of his time, referring to him only as an

‘illustrator’. It is true that many of his paintings depict small town America, but these were the very places that had

suffered so terribly during the Depression. Despite this lack of critical acclaim, he is loved by many Americans and

appreciated in the Norman Rockwell Museum. He has been

exhibited across America and adopted as the Official State

Artist of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts,

demonstrating the lasting public appreciation.

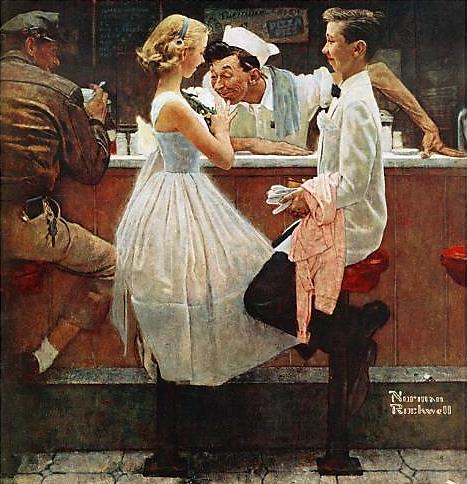

‘After the Prom’, Saturday Evening Post, 1957, Norman Rockwell 1894-1978

Art in America between 1860 and 1960 differed from that in Europe as artists worked primarily for magazines and so this was uniquely the ‘Art of the People’. Both Homer and Remington worked for the leading magazine Harpers Weekly and Rockwell for the equally nationwide, Saturday Evening Post and Parrish with his universal calendars.

Their work was designed to appeal to the nation as a whole and did much to give the nation a shared culture, at a time of great internal challenges. Whilst ‘serious academic art critics’ may disparage their works, the people obviously valued them. Their ‘media’ art was not made for museums and galleries, but for their homes and made their pictures part of people’s lives. The art of the people.

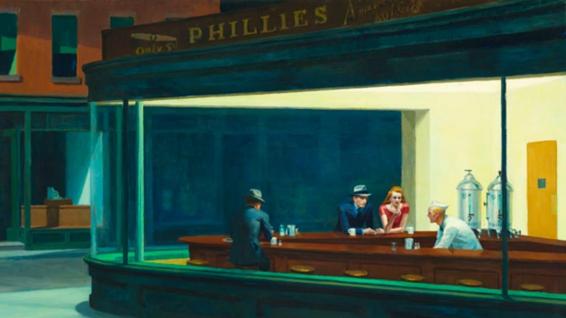

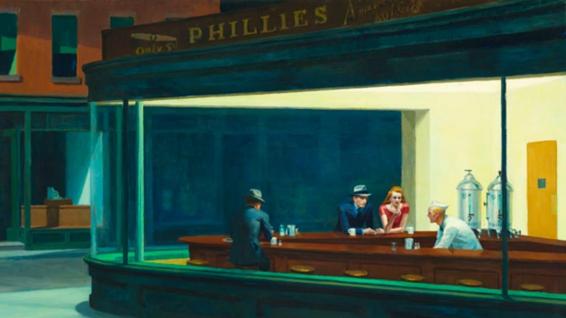

In contrast to these ‘magazine’ artists,

was the simultaneous production of

‘realist’ works that showed another side

of life. These paintings were taken up by

art galleries and so recognised by the art

academia.

This realism could show the isolation that

can be experienced in towns or cities,

where lonely people fail to interact with

each other. The image is one of being

alone or of a fleeting meeting, where the

viewer is outside, almost acting as a

‘peeping tom’, in the cheap, bleak

surroundings. The painting is more of a

commentary than an inspiration for

covers designed to sell magazines.

‘Nighthawks’, Edward Hopper, 1942

A Post-war boom

This bonding of spirit and shared vision was to come to the fore when America entered the second World War in 1941, following the surprise Japanese invasion of Pearl Harbour in Hawaii. America had new industries that could easily transfer to military equipment and provide a huge surge in power to both Europe and the Far East. The immediate successes brought a pride and a moral leadership across the world. America escaped bombing to leave the war with her industries intact, and her economy ready to boom. A surge of optimism in a world where the ‘bad guys’ had been beaten and destroyed, heralding new innovations and a confident new art.

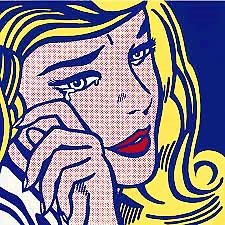

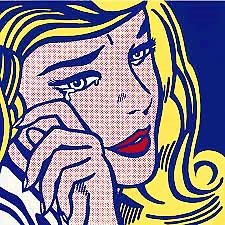

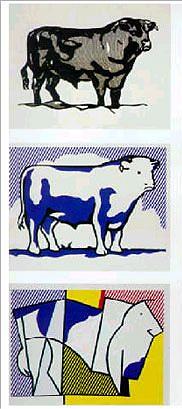

In this consumer dominated society, it was ‘pop art’ - so called as popular items were used - that caught the public attention and none more so than Roy Lichtenstein in 1960. He was to lead the new generation of commercial pop artists, who were to ride on the backs of the commercial world. They reflected an American society to which all Americans could relate to and which the rest of the world would be swept away by their boldness. (7) Lichtenstein’s work was

drawn directly from comic

strips and so drew criticism

not just from the art

academia, but also from the

public where many

considered him a ‘copyist’,

with Life magazine headlining

‘Is he the worst artist in the

US?’.

‘Whaam’, Roy Lichtenstein, 1963 2

panels totalling 1.7m by 4.0m

But his work attracted a strong audience, at home and around the world, possibly enhanced by the developing art market where works were bought as an investment. One criticism is that Lichtenstein never acknowledged the original artists he copied or paid any royalties, although he remarked that ‘I am nominally copying’. (5) One cartoonist commented that ‘Lichtenstein did more or less for comics that Andy Warhol did for soup’. (Book 6) One aspect where his work differed from the

original was his enlargement of the Ben-Day

dots that formed the colours of 1950’s

comics.

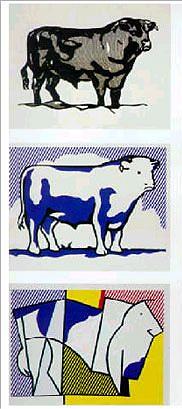

After some 3 years Lichtenstein largely

dropped this pop style to experiment with a

range of influences, including cubism. Here

he remarked ‘What I am painting is a kind of

Picasso done the way a cartoonist would do it ….

I’ve always been interested … in Picasso’. This

image shows a picture deconstructed into

cubism.

‘Crying Girl’ Roy Lichtenstein, 1964

Bulls Going Abstract, Roy Lichtenstein, 1982

With its early embrace of the media, America trod an altogether different artistic route than older European countries.

Their art was far more consumer oriented and so arguably had a far greater impact on society and American culture, than their European cousins. Certainly, they are more direct and more related to the worlds in which they were produced, otherwise they just wouldn’t sell. A key aspect of American society.

This culture and society carried the United States through years of war and depression, to an optimism that continues to this day with an often repeated quote by historian James Adams in 1931:

‘The American dream is that dream of a land in which life should be better, richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each according to his ability and achievement’.

Summary

80 years after independence, America was gripped by Civil War between the South where African slaves were worked in the cotton and tobacco fields and the North who looked to end this slavery. The country was split in two with bloody battles until 700,000 lay dead. The South was destroyed and would take years to rebuild and overcome the resentment that divided the country.

The country turned to the immense lands of the West as settlers formed wagon trails over endless plains and rugged mountains. People were swept up with the beauty of the interior and with the romance of new territories, but lands that had been occupied by millions of native Indians for millenia, but who suffered to the point of extinction.

The bravery of the ‘cowboy’ was to enter the imagination as he overcame the odds and the West was won.

The world was opening up with influences shared between Europe and America and the new art of Impressionism was brought to America. Women began to gain greater recognition, with female artists achieving success in the capital of art - Paris. But their opportunities were still limited to domestic scenes or portraits of other women.

After the First World War, the economy boomed, but then overheated as consumers and companies over-borrowed and money became tight. A European collapse heaped further pain as consumers reined in their spending, hitting production and jobs. Unemployment soared, farming collapsed, banks collapsed and the stockmarket collapsed. The Great Depression had arrived and people formed bread lines for food, until the ‘New Deal’ brought an injection of government monies to rebuild the infrastructure and the economy.

A new optimism came through in movies and magazines as America struggled to recover and find a sense of unity and national identity. A new picture of America emerged of a strong and vibrant country, encouraging a confidence for consumers and to the rest of the world. A shared culture emerged that would drive America through the Second World War and onwards.

America’s art responded through the media, appealing directly to the people.

America emerged from the Second World War with her industries intact and a post-war boom arrived. With a confidence in the country’s power and moral standing, people relished new expressions and ‘pop-art’ emerged that used everyday products in an art directly recognisable by the people. America was truly a consumer society.

Information sources

(1)

https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/21936/7-civil-war-stories-you-didnt-learn-high-school

(2)

https://www.history.com/topics/immigration/u-s-immigration-before-1965

(3)

https://www.history.com/news/native-americans-genocide-united-states

(4)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bury_My_Heart_at_Wounded_Knee

(5)

https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-ushistory2os2xmaster/chapter/the-depths-of-the-great-depression/

(6)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Norman_Rockwell

(7)

https://lichtensteinfoundation.org/biography/

A BBC series ‘Civilisation’, provides a history of art and society from the middle ages to the present day, over 13 episodes

https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/group/p050q44y

Books in this Series

Book 1 Pre-History & Greece to Rome Olympics & Empires 2 The Renaissance in Italy The Patron & The Artist 3 The Four Princes War, Terror & Religion 4 Northern Europe Revolution & Evolution 5 The American Dream Depression to Optimism 6 The Modern World The ‘..isms’ of Art 7 Past Voices Stories behind the Art All free e-book downloads

e-book website: artystories.org

The history of life and art across

centuries, of changing societies

and changing cultures.

‘I think the concept for your work

is both creative and engaging for

young people. The links between

art, history, society are clear in

the outline you provide and the

opportunities to stimulate young

people’s interest and imagination

are evident’.

Sir Nicholas Serota,

Chairman,

Arts Council, England

‘The Oregon Trail’, Albert Bierstadt, 1869

Society makes art and art defines society’s culture