ARTY

STORIES

Book 4

NORTHERN EUROPE

Revolution & Evolution

Art and life

across the centuries

Ian Matsuda, FCA, BA (Hons)

for

Noko

Copyright

Ian Matsuda, FCA, BA (Hons), 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, transmitted or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher or licence holder https://www.artystories.org email: info@artystories.org

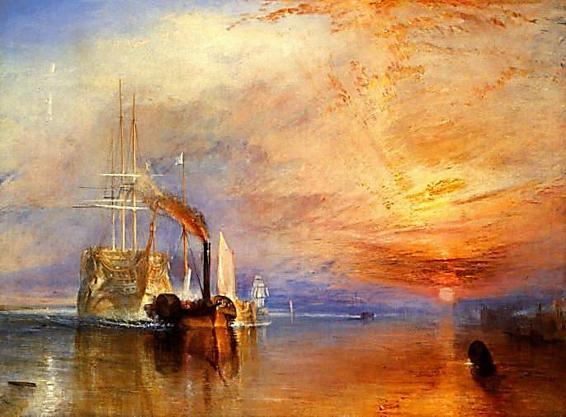

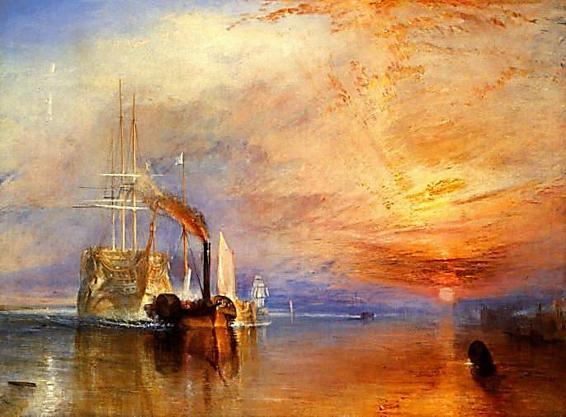

Liberty leading the battle, 1830 Eugene Delacroix, Louvre, Paris The Fighting Temeraire, tugged to last berth, Turner, 1839, National gallery, London

‘ARTY STORIES’

Art & Life across the centuries

‘Seeing people’s lives brings their art to life’

See the stories that made the art – the times – the place – the people Book 4: NORTHERN EUROPE – Revolution & Evolution

A refreshingly entertaining introduction to the world of art through 5,000 years of tumultuous history This fourth book covers the 16th to 19th C with a ‘golden age’ in the Netherlands, revolution in France, industry in England.

The Dutch established new colonies in the East Indies and in a settled society, introduced new techniques of painting on oil and canvas. But across the border in France the people were oppressed into poverty, breaking out into revolution that swept the old aristocrats away in a great bloodletting. England rushed to introduce new protections for the poor in the new industrial revolution - education came to the people. The ‘new’ democratic France found a new art of impressionism.

Ideal for student and art lover alike

Supported by the Arts Council, England as:

‘creative and engaging for young people’

‘the opportunities to stimulate interest and imagination are evident’.

Centuries of great art are a gift to us all

Books in this Series

Book 1 Egypt - Greece - Rome Empires come & Empires go 2 The Renaissance in Italy The Patron & The Artist 3 The Four Princes War, Terror & Religion 4 Northern Europe Revolution & Evolution 5 The American Dream Depression to Optimism

6 The Modern World The ‘…isms’ of Art

7 Past Voices Stories behind the Art All free e-book downloads

https://www.artystories.org

Book 4

NORTHERN EUROPE

Revolution & Evolution

CONTENTS

• Northern Europe – the Netherlands

• Children’s games and town festivals

• The French revolutions

• Romance in England

• The Battle of the Artists

• Summary

• Sources of information

Northern Europe – The Netherlands

Outside of Italy and prior to the Renaissance, art was taking very different paths in very different worlds. It was the Dutch who had first taken paintings to a new level with oils on canvas. Trade brought rich customers who wanted bright paintings to hang on their walls and to send home.

At the start of the 15th century the Dutch artist Jan van Eyck had developed painting with linseed oils, building up translucent layers for a ‘glazed’ finish to enhance the colours. Through their trade routes from the Dutch East Indies, they could import bright pigments from as a far away as Baghdad and exotic Persia. Colours came from nature, not manufactured and the deep blue of lapis came from Afghanistan. Millions of years ago lapis was thrown up from 35-40 km underground where the extreme heat and pressure had transformed yellow sulphur into a deep ultramarine blue – worth more than gold! Using oils also meant that the Dutch could paint on a ship’s canvas rather than oak board and the canvas could then be rolled up and sent by sea or overland in smaller and faster carts. Paintings became more available and much more exciting. (1) The Dutch already had established routes for their art as the Netherlands became a centre of trade between the north from England, Russia and Scandinavia and the south with France, Italy and Constantinople (now Istanbul).

Bankers provided letters of credit for payment and these wealthy bankers had come from Italy and wanted to send some of this wonderful new art back home. At that time Italian artists were still using an egg-based paint (tempura) and could not produce the same impression of depth and colour achieved with oils. The bankers spent much of their wealth on portraits, 70 years before the Italian painters such as Michelangelo and Leonardo.

Jan van Eyck was the first to produce realistic portraits that reflected the sitter’s character. He worked for the fabulously wealthy Duke of Burgundy, acting as ambassador and spy with his travels termed ‘secret commissions’. His artistic notoriety and the patronage of the Duke, opened many doors otherwise held closed.

This self-portrait by the artist Jan van Eyck shows him looking challengingly at the viewer with an inscription reading ‘as I Eyck can’. With the exaggerated folds of the bright red ‘turban’ he was showing prospective customers the colour, detail and accuracy of his own work. These true to life portraits were a new skill appreciated by the aristocracy to favourably display themselves and when looking for a wife from another country could see not just her looks, but gave an insight into her character.

Van Eyck displayed an incredible level of detail, as in these excerpts from his Ghent altarpiece. The detail and richness of colour that he achieved stands out and also shows how he was a master of portraying the brilliance of jewellery.

Self-portrait, Jan van Eyck, 1433 National Gallery, London

The altarpiece was opened on feast days to show rich religious symbols Ghent Altarpiece, Jan & Hubert van Eyck, 1432, St. Bavo’s, Cathedral, Ghent. (Excerpts are from the top 2nd and centre panels)

Children’s games and town festivals

But as all these bankers, Kings and Dukes lived these privileged lives, what of everybody else, the poor – what were their lives like in Northern Europe in the 16th century?

Well at first with all this trade work, was plentiful and the people in the towns lived well. So, they began to have larger families, but with more mouths to feed, the price of their food escalated. Then as the children grew up, there were more people to work and so wages fell, pushing them back into poverty. A life of swings and roundabouts. Their diet was black bread and peas, washed down with lashings of beer, an average of one litre a day each. The water could be too bad to drink, so it had to be beer. But they lived in close communities and celebrations and festivals were their escape from the grind of life, both for children and for adults.

One Dutch artist 130 years after van Eyck, was Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Rather than paint for the rich, he chose to record village life, providing a unique window into a now vanished folk culture and rural society. Bruegel started out in life as a designer of prints, but he moved to Brussels and switched to painting and unusually at that time, depicted peasant life. Bruegel produced many scenes of rural and town life during the 16th century and as his sons and even grandsons were to continue this work, he came to be called Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

His paintings became sought after by wealthy Flemish collectors, who were drawn to the distinct style of dozens of small figures engaged in individual pursuits, seen from a high viewpoint. This was very different to the studied and structured paintings of the day where all was carefully staged in a rigid pose.

Without these paintings we would not have such a vibrant picture of life outside of the cities.

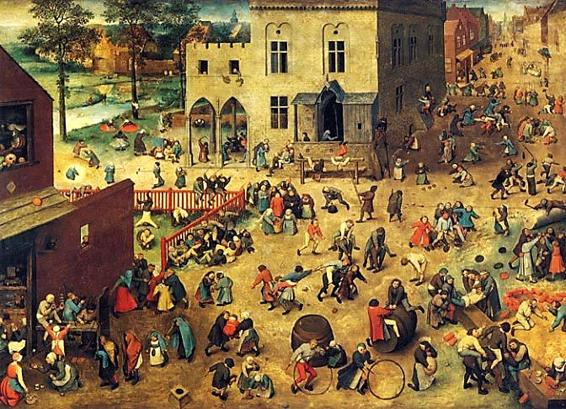

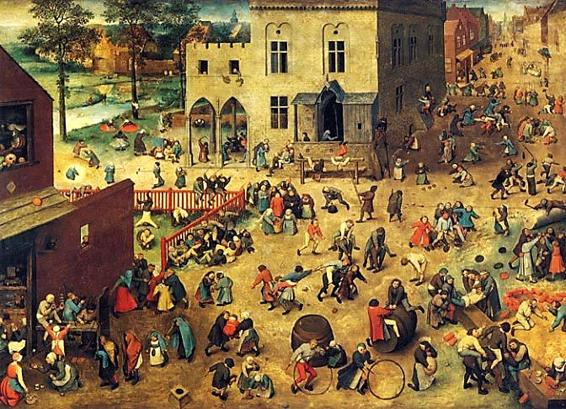

Amazingly in this painting,

from almost 500 years ago,

are 80 children’s games.

Playing with dolls, a water

gun, an inflated pig’s

bladder (like a football),

masks, swing, climbing,

handstand, somersault,

tiddlywinks, marbles,

pretend wedding, blind

man’s bluff, soap bubbles,

riding a broom, ‘hide and

seek’, a toy animal, walking

on stilts, pole vaulting,

leapfrog, rolling a hoop and

that’s just 20! These are

games still played today.

A town full of children.

‘Children’s Games’ Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1560, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna There was a poem of the time that ridiculed adults as playing foolish games in their lives like children, when perhaps they should know better, as in the next painting.

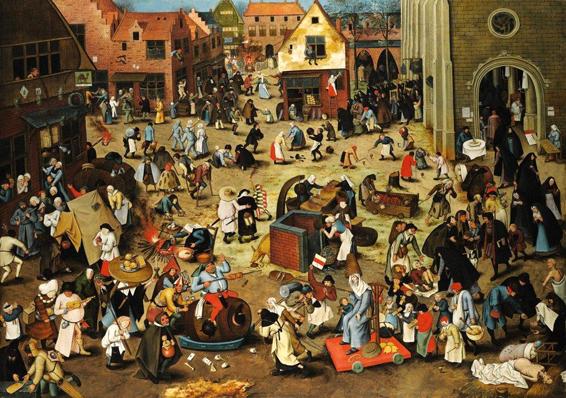

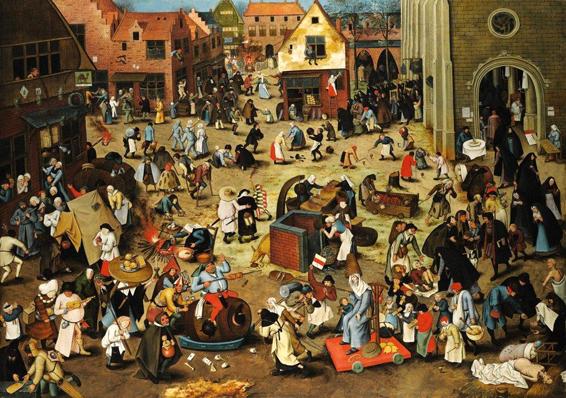

This painting has an

interesting contrast with an

inn (pub) on the left-hand

side, with boisterous party-

goers dancing to a band to

celebrate carnival. While on

the other side is a church

with nuns in black observing

prayer and Lent, tending the

poor and the sick. One

celebrating the church

religious festival and the

other the carnival party. Each

year there was a ‘battle’

between the two sides with

competing floats. The fat

man on the beer barrel with a

pie on his head pushed by a

‘clown’, contrasted by ‘Lady

Lent’ on the other, drawn by

a nun and a monk. Town Festival, ‘The Fight Between Carnival and Lent’, Pieter Bruegel the Elder 1559, Vienna In the middle of the square is the well that serves everyone with water, while at the back of the square are people preparing food and wine. On the left is a scene of joy that food is plentiful and then on the right the religious reminder of the tougher times to come before spring. Both the harvest and the church are important.

The French revolutions

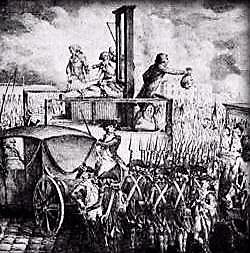

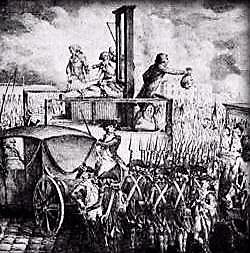

As the 16th and 17th centuries drew to a close the Dutch had entered a ‘Golden Age’ (Book 3), while in France the poor began to increasingly suffer with grinding poverty and oppression, only worsening through the 18th century. France was bankrupt from supporting the American War of Independence against the hated English, with its people starving from 2 years of drought. The people rose up and the excessive and ridiculed monarchy -

together with the crushing aristocrats - were thrown into jail. Here they promptly came before the Tribunal and people’s judge to be found guilty. They would then immediately be taken to have their heads cut off by the infamous ‘Madame Guillotine’. A dreadful and swift retribution in the ‘Terror’.

Dragged on a cart through the narrow, cobbled streets, overflowing with sewage, they faced crowds of ‘citizens’

crying out for their blood. Terrified and huddled together they would reach the dreaded guillotine and wait to watch those before them being beheaded, before it was their turn to walk up the steps. Between 1793 and 1794, 17,000 would make this terrible journey, to the cheers of the crowd each time the guillotine fell. (2)

Following this revolution, Napoleon became Emperor and took France on a doomed adventure to conquer all of Europe. This was stopped 16 years later at the battle of Waterloo in 1815, throwing France into disarray and heralding the return of a monarchy. But this new monarchy was itself to become deeply unpopular as they sought to overrule the government and were themselves removed by a second revolution in 1830. France struggled to keep its titular monarchy, but it would finally be removed in 1848 when a Republic was declared with an elected President – a government remaining in place to this day.

Men and women were equal in this struggle

for democracy and women were portrayed

as leading men into battle against the

aristocrats’ soldiers. Seen here in the second

revolution, leading a charge over the bodies

of the fallen soldiers. Baring her chest to the

enemy she leads and turning with the French

flag in one hand and a musket in the other,

urges the men on, to raise their tempers for

the battle

The painting is a celebration of the 1830

victory of the people’s republic to go forward

into the future, with a cry of ‘Liberté, egalité

and fraternité’ (‘Liberty, equality and

fellowship’) A cry that is still heard in the

French national anthem today.

Liberty leading the battle, 1830 Eugene Delacroix, Louvre, Paris In England they chose another way, without terror and blood, but one that still empowered the people.

Romance in England

When Henry Vlll broke away from the church in Rome in 1532, he destroyed all the powerful and rich abbeys and discouraged religious art in the churches. (Book 3) England was now outside of the Italian Renaissance and art tended to be commissioned by the King and the landed gentry in staged portraits, particularly miniatures.

Sculpture was limited to tombs.

It was not until a further 200 years later in the 19th century, that the industrial revolution was to bizarrely develop an art for the ordinary people and then in romantic paintings. A contradiction, but also a progress.

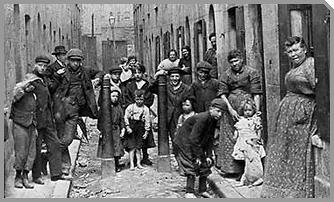

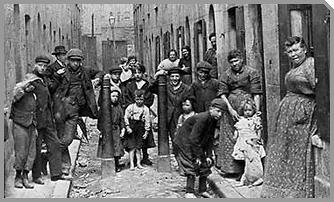

In the Victorian age; 1837-1901; living conditions in the new industrialised towns were terrible, with dreadful housing in slums and dangerous working conditions. These brought poverty, poor health, hunger, high child mortality and minimal education. In these living conditions people will despair and foster a dangerous resentment. These later photos record the people and their conditions – still very poor.

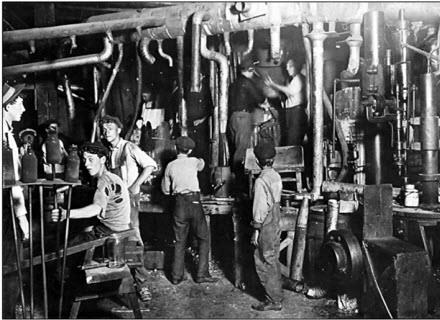

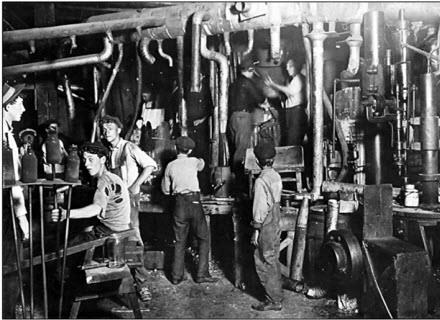

Whitechapel, London, 1880’s Glass factory 1908

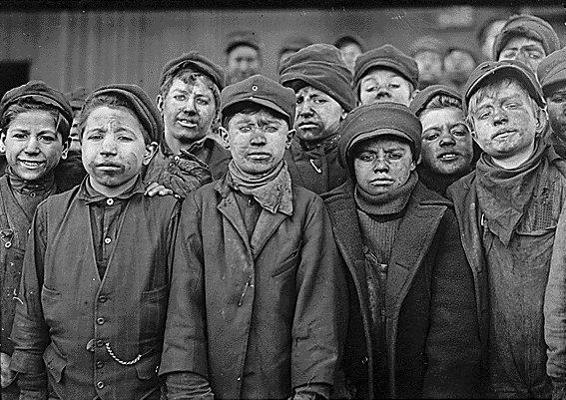

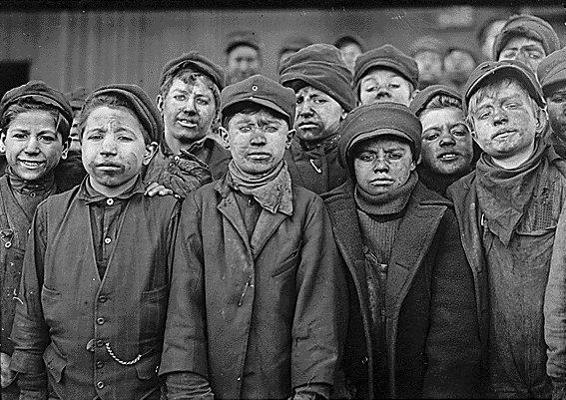

This suffering in the early 19th century was a recipe ripe for revolution as happened in France and one that the British government sought to avoid. They introduced a succession of reforms giving people the right to vote (although women had to wait another 50 years), together with worker’s trade unions. Public health improved with clean water through sewage removal and education was compulsory for all children. Children as young as 5 or 6

worked 10-15 hours a day, often barefoot with no shoes, in dreadful factories and mines, their lives taken away.

This first reform still only raised the minimum age to 9 years old and a maximum 12 hour working day. (3) Coal mining 1911 Mill workers 1910

This suffering has been immortalised in the hymn ‘Jerusalem’, as ‘those dark satanic mills’ and reflected in the streets full of the noise of horses with metal coach wheels rattling over cobbles and street sellers and paper boys shouting their wares. London streets stank of effluent, collected by the ‘night soil man’, otherwise running down to the Thames, carrying cholera. Only with the ‘great stink’ of 1858, was Parliament moved to build sewers.

As the reforms were enacted, public bodies sought to engender a pride and ownership in their towns, with grand public buildings, as in ancient Athens. (Book 1) A national pride grew as the British Empire strode the world and under Queen Victoria, ‘Great Britain’ stamped its place in the world and in people’s lives.

People’s lives became far better and with the

introduction of holidays, far more enjoyable. Factory

owners saw the benefits of people being healthier

and happier and encouraged a pride in their town.

Public buildings for local councils and libraries were

built and art galleries opened, mostly in the Greek

style with impressive and strong pillars. For the first

time the ordinary man had a civic pride and could

see art in his local town and it was free for all,

inducing a sense of ownership.

A new urban society grew, with greater prospects,

leading to a rapidly expanding middle class.

Victorian Leeds Town Hall, 1853-1858

In the new art galleries, the most popular paintings were in romantic settings. These gave people a dream out of their day-to-day lives in smoky and dirty towns, to a beautiful, sunny countryside. Artists looked to portray an abundance of detail with the intense colours of nature and not the elegant poses that the rich had commissioned. This art became the art of the people, not religious art or views of the upper class, but of the dreams in ordinary lives. People now had something to imagine, away from the industrial grind.

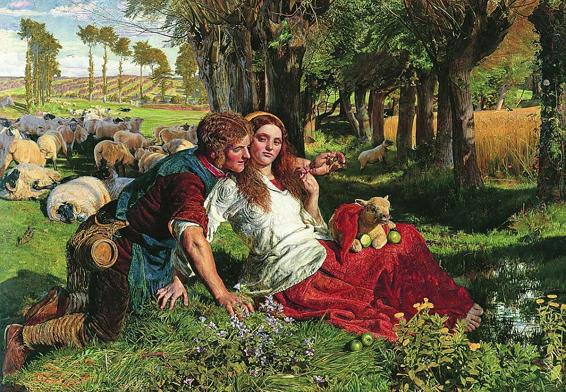

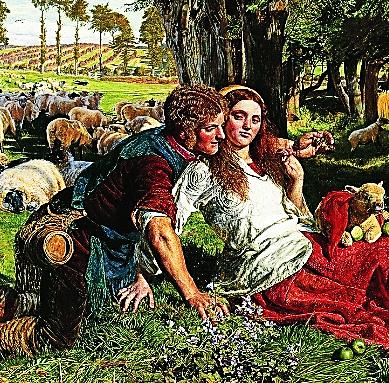

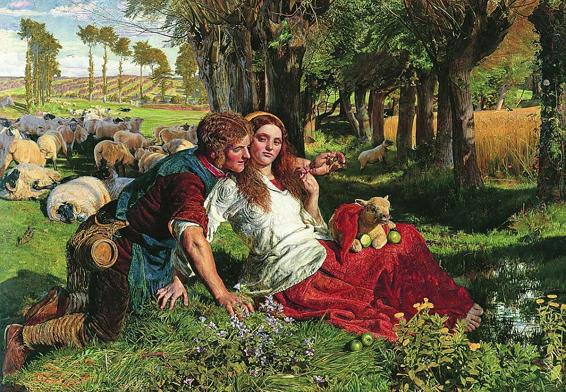

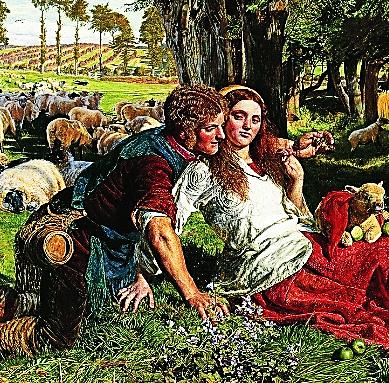

One artist who led this rebellion against the upper class and their establishment, was Holman Hunt.

Romantic and doomed love was a melodrama

loved by the Victorians. But not all paintings were

sad and some told of happiness and love, with

scenes of an ideal England among the country

fields, far from the smoke of industrialised towns.

The shepherd neglects his sheep who are

wandering into a corn field, to be with the girl,

showing her a butterfly that he had caught for her.

The rosy complexions and rich landscape of

sheep and corn, show a land of goodness and

plenty, with time for love.

The painting is still in the Manchester Art Gallery

The Hireling Shepherd, 1851 William Holman Hunt

Manchester Art Gallery

In strict and conservative Victorian England when women had little rights, love was a distraction from the greyness of everyday life. It was their ‘cinema’ and their escape to other worlds, with an art for the people.

Poetry and books began to be popular as education helped people to learn to read. Romantic dreams in the Victorian age flourished with novels by Jane Austen and Charles Dickens and poems by Wordsworth and Tennyson. One popular romantic poem was The Lady of Shalott, written by Tennyson in 1832. A sad tale of all consuming and tragic love. True Victorian melodrama.

A lady lost to a doomed love

The Lady of Shalott, 1888, John Waterhouse,

Tate Britain, London

From the poem by Alfred Lord Tennyson

The story in the poem is of the Lady of Shalott who lived ‘by the island in the river, flowing down to Camelot’ –

fabled castle of the medieval knights. There was ‘a curse on her if she stay to look down to Camelot’, so she only looked out through a reflection in ‘a mirror clear’. But she was lonely and one day a knight, ‘bold Sir Lancelot’ rode down by the river ‘and as he rode his armour rang’, she turned to look and ‘the mirror cracked’ and she cried ‘the curse is come upon me’. But, she had fallen in love with ‘his coal black curls’ and ‘down she came and found a boat’

and ‘she floated down to Camelot’. There, ‘singing in her song, she died’ as her curse had predicted, Lancelot looked down on her and said ‘she has a lovely face, God in his mercy lend her grace, The Lady of Shalott’.

The Battle of the Artists

While life improved in England, there had been smaller revolts right across Europe in Paris, Vienna, Berlin, Milan, Rome and Venice. All against the upper classes as a call from the poor for greater freedoms.

Revolution would become evolution.

In 1870 war broke out between France and Germany and a penniless young artist, Claude Monet fled to London. As a young man Monet had been impressed by the work of Joseph Turner, a prolific English painter.

Turner had suffered criticism of his ‘impressionist’ paintings, described as ‘soapsuds and whitewash’ with critics saying that ‘calling it a picture would be an abuse of language’ (4) Paintings that we admire today.

Painted by Turner, ‘The Fighting Temeraire’ had

boasted 98 guns and had fought at the Battle of

Trafalgar in 1805. Here, Turner shows us as she is

being towed to her last berth in 1839, to be broken

up for scrap. Silently sailing into her last sunset,

with the light falling on the ship to conjure a white

ghostly yet colourful image - to haunting effect. We

can see how he has framed the sky, with the rich

colours reflected in the sea.

‘The Fighting Temeraire, tugged to last berth’,

Turner, 1839, National gallery, London

It was Turner who first had caught the emotional

impression and swirl of colour some 30 years

before Monet, instigating a major evolution in art.

Monet was to hold this inspiration and develop his new ideas on his return to Paris.

In France, there had been a public outburst of freedom of expression, with the people looking to a new future, challenging the old ways. This spirit of rebellion saw artists rejecting the traditional paintings of the ‘high art’

picturesque and staged scenes. Their entirely new approaches brought the ‘Battle of the Artists’ to the streets of Paris. They wanted to catch life in the moment, just as it is happening, as an impression of that moment with the changing light. But, rejected by the official art salons, they had to fight to even get their paintings shown.

Gone was the carefully lit studio and studied pose. Artists set up their easels outside and painted with no preparation, in rapid short brushstrokes or scraped on with a palette knife, applying layers of thick oils on wet oil paint for a texture and softer mix of colour.

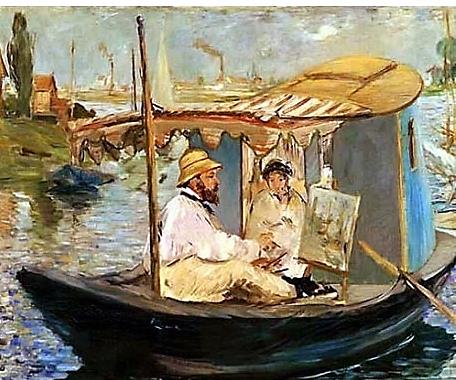

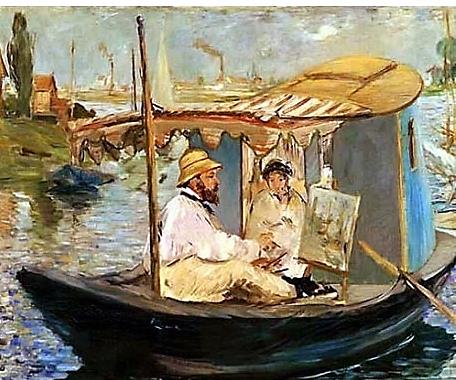

The introduction of synthetic oil paint in tubes in vivid colours, meant that artists were free to paint in the open air, without having to mix colours. One even set up his studio on a little boat so that he could catch the light as it was reflected in the water and how it changed as the sun moved between clouds. Using a strong contrast between light and dark made the colours more vivid and more absorbing to the

viewer. This was an art of the streets – and of the rivers!

Be it Revolution or Evolution, Impressionism had arrived.

Monet on the river, by Edouard Manet, 1874, Munich

The painter in the boat was Monet, still a penniless young artist who would go on to become one of the most famous painters in the world. But he had to fight to have his paintings shown and his art recognised.

With their work rejected by the established galleries, in 1874 the artists formed an association and held their own exhibition which the critics attacked as a ‘disaster’, exclaiming ‘my horrified eyes behold something terrible’. Crowds from the upper-class establishment, packed to get in, but only to ‘rock with laughter’ at the ‘cruel spectacle that met their terrified gaze’. Much the same criticism as aimed at Turner, 35 years earlier.

Claude Monet

1860-61, aged 21

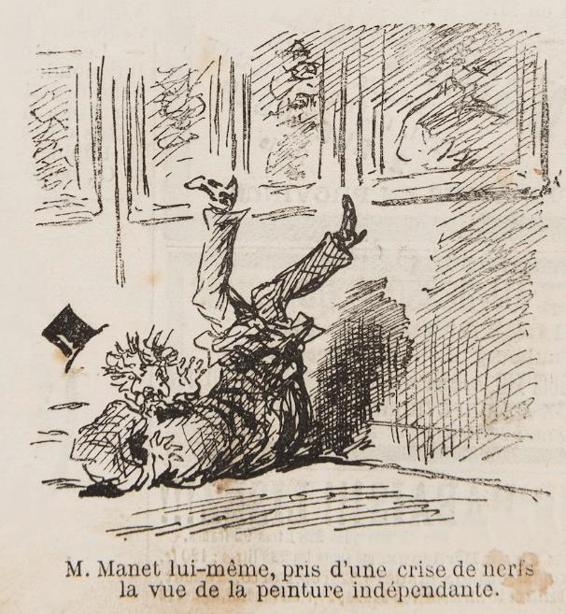

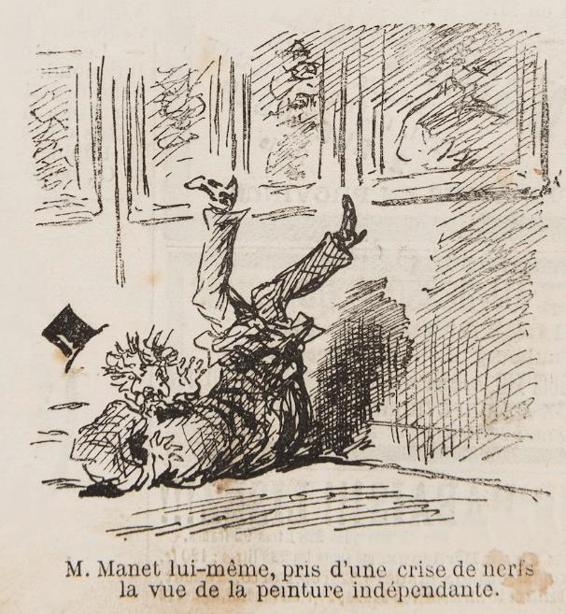

The newspapers laughed at these new works, portraying people as

collapsing from shock in front of the paintings.

The upper-class art ‘establishment’ was under challenge.

Nervous collapse on seeing the new ‘independent’ art

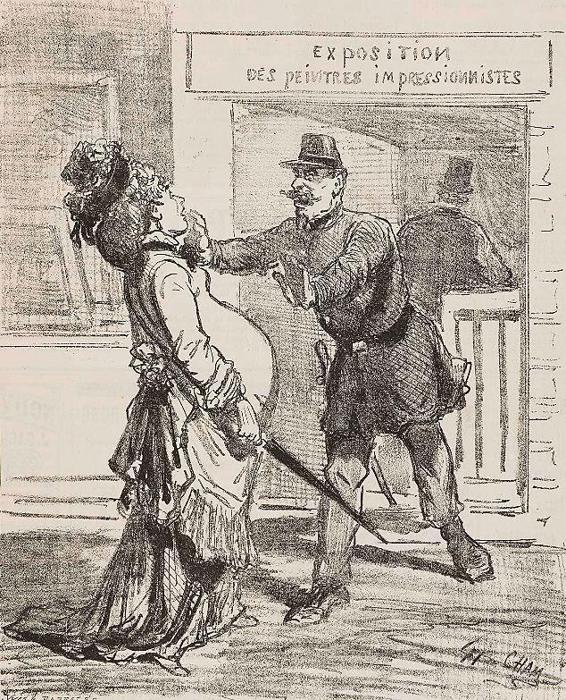

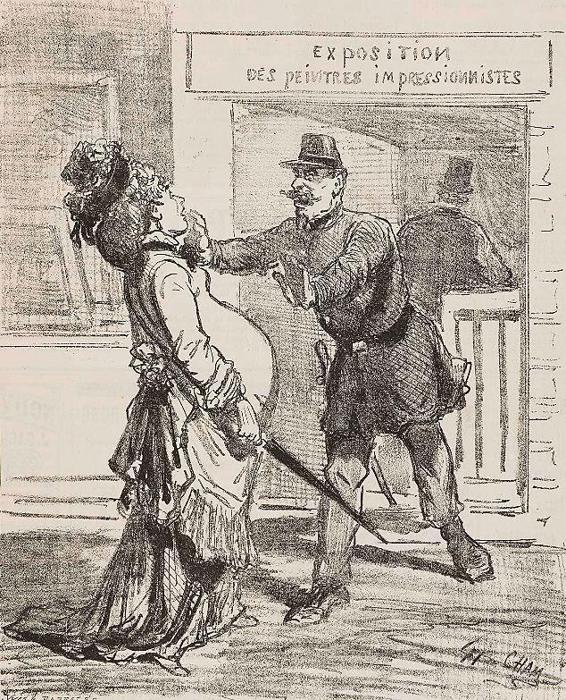

Women were warned to stay away - even though for the first

time women artists were included. (Book 5) The outcry from the

critics knew no bounds.

Everyone laughed.

But these critics were themselves made to look fools as the

public – the people – took the new style to their hearts as a

symbol of their new world, in a society of ‘today’ and of the

future, not of the past.

No entrance for pregnant women to the exhibition of the ‘Impressionists’!

The impressionists set out to portray how the eye sees life in a glance, spontaneously as an impression, not as a focused image. People could now take photos themselves for an accurate image and so painting came to serve a new, aesthetic purpose. The technique of quick brushstrokes to capture movement and light, enabled their paintings to catch real life in streets, cafes, cabarets, across rivers, people at work or at play, not in idealised studio situations. This was a new form of art that people saw as a rebellion against the conservative

‘establishments’ of the upper classes, with an art portraying their own lives, that they took to be their own. (5) Everyday views were transformed as the artists introduced new contrasts of dazzling colours. Society found an art that matched their new world, an art that reflected society and so helped establish a new French society.

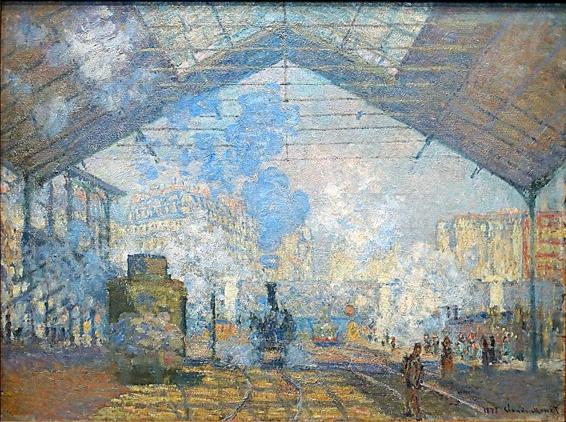

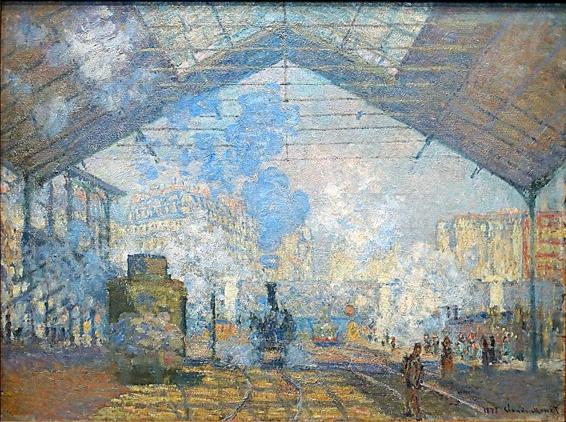

On returning to Paris from London Monet burst into his own style, painting real life in the outdoors.

Just three years after his first exhibition, Monet’s

style had evolved to this evocative painting.

Monet caught the light streaming down through

the glass skylight, through the clouds of steam as

the train emerges from this confusion into the

bustle of a station, throwing steam over the city.

Under the clear cold blue sky of a winter’s day,

the scene is framed by the dark blue of the roof.

The impression is of a movement as a spectator

experiences all of the sensation of actually being

on the spot. So inspired was Monet, that he

made four versions of the same scene.

Gare Saint-Lazare, Paris, Monet, 1877

National Gallery, London

The steam is portrayed in blue, pinks, violets, tans, greys, whites, blacks and yellows, showing how colour was used to create an impression rather than a factual picture. Standing in front of an impressionist canvas is to be absorbed into a pool of colour and drawn into the picture, making the prints so popular with people today.

But it was an art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel who had met Monet in London, who had kept the artists going, buying up their works in groups of 30-50 paintings.

This at a time, when no-one else would go near them and so he kept the artists from bankruptcy. The artists would even exchange their works just for oils, so they could continue working.

These artists painted what they wanted, not what any patron wanted.

It is Paul that we have to thank for the impressionist paintings today.

Paul Durand-Ruel, 1866

Paul saw this as a ‘battle’ to have these wonderful paintings accepted. He became such a collector that he also nearly went bankrupt himself, collecting hundreds of paintings that he couldn’t sell. Then in 1885 he was invited to take 350 paintings to an exhibition in the USA, where they were snapped up as a new art for a new country.

Which is why today there are so many impressionist paintings in American art galleries. (Book 5) Without this art dealer, the impressionists may not have been able to continue and we may never have heard of the great artists such as Monet, Renoir, Pissarro or Manet, all of whom he kept afloat at his own cost. Since the 15th century, every artist has needed patronage, be it a collector or a gallery. The difference this time is that it is the artist who determines the subject, the content and the form of representation, not the patron.

Monet was to return to London 33 years

later and here he found the damp, misty

light to be so different from Paris. He

portrayed impressions of buildings peering

through the gloom, where he caught the

evening sun setting through the soft fog

that blew from the factory chimneys. He

created a frame of the sky at the top and

the river at the bottom, reflecting the

sunset of the sky. Surrounded, the Houses

of Parliament sits solidly in the centre in

the cold blue of a winter’s day.

The Houses of Parliament, London, Monet, 1903

National gallery, London – one of 19 similar views!

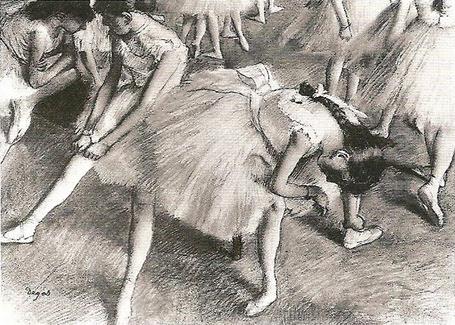

But not all impressionists used this style. Degas also looked to catch images in the moment, but not in the avalanche of colours used by Monet. He was particularly interested in portraying ballet dancers rehearsing and self-occupied in their own thoughts, rather than posed on a stage.

Degas had rejected a career as a lawyer to

become an artist and then rejected the

conservative paintings of the establishment and

joined the impressionists. But Degas again took

his own route, not painting outdoors and instead

turned indoors to the dance studios.

He liked to catch the dancers from unexpected

angles, in a casual position, where their

characters can be seen resting, unaware of the

artist. We see the dancer bent forward, holding

her ankle in a moment of

relaxation.

Awaiting the cue, Degas, 1879

Private collection

At the start of the 19th century, ballet shoes had heels with no support for toes and the dancers could be heard clunking across the floor. Dancers were only set free with the introduction first of flat ballet shoes, then later with a platform to support the toes. So, ballet dancers could then leap and by the end of the century, could stand poised on their toes, ‘a pointe’. Unlike the early leather soles, the sole was made of satin and the dancer was almost silent. The dancers representing swans in Swan Lake, could now glide to the music and Romeo could run to Juliette without a crashing of feet to disturb the romantic illusion.

So, ballet assumed an artistic style and a genre in its own right, becoming part of society and its culture.

This new evolution in ballet was happening at the time that Degas was visiting the dance studios, so he could portray the new grace of the dancers. (6) But as he grew older, his eyesight began to fail him and Degas turned to sculpture, producing this beautiful study of a young ballerina.

The ballerina shows the stress in her face of aiming for

perfection. Only a girl of 14, she is lifting her head and

arching her back, with studied pride. Degas dressed her in

a ballet dress that emphasises her youth and poise.

Degas made this in a reddish wax and it was only after his

death that his relatives had a bronze cast made.

So, with his realism Degas sits between impressionism and

tradition.

Little Dancer, aged 14, Degas, 1881

Metropolitan Museum, New York

Summary

The Dutch had introduced new oil paintings on canvas, allowing vivid paintings that were also easy to transport.

Rich, detailed and lifelike works, that brought medieval art out of the ‘dark ages’.

In Northern Europe we saw how people lived and how children played. As people travelled far less than we do today, each village and town had a strong community that came together for harvest or religious festivals. They were poor, but they knew how to enjoy themselves!

But across Europe there came revolution as the people rose up from their poverty and hunger, to strike down their rulers and the upper classes who grew rich on their work. In France, the dreadful Madame Guillotine cut off the aristocratic heads as the people shouted, ‘Liberté, egalité and fraternité’.

In England, the government had moved to give people better conditions and better lives and rather than total revolution, people found a pride and went to new art galleries in their towns to see romantic paintings. Pictures of a world that they could only dream of - away from the work and grime of their everyday lives, to enjoy a new urban society.

But a new more prosperous world was just around the corner.

A new art of impression evolved that challenged the old traditional art and society.

An art of a different beauty that the establishments tried to throw out, only for the people to shout its praises in their new world of freedom.

A new art for a new, modern society, with new cultural values and aspirations.

Then a realistic impressionism with a life-like model portraying a juvenile arrogance. The dancer’s expression juts out to the world as if to say ‘this is me and I am good!’

Now art has its own expression, free of any demanding and manipulating patrons.

‘From revolution to evolution’

Sources of information

(1)

https://www.webexhibits.org/pigments/intro/renaissance.html

(2)

https://www. softschools.com/facts/world_history/french_revolution_facts/2206/

(3)

https://www. bbc.co.uk/education/guides/zvmv4wx/revision/4

(4)

https://www. telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/11110438/JMW-Turner-art-master-and-polemicist.html

(5) https://www. metmuseum.org/toah/hd/imml/hd_imml.htm/

(6) https://en. wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_ballet

A BBC series ‘Civilisation’, provides a history of art and society from the middle ages to the present day, over 13 episodes

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLXC6RzjHc2wugLza1kMWN_CRBuKRqQNTw

The history of life and art across centuries,

of changing societies and changing cultures.

‘I think the concept for your work is both

creative and engaging for young people.

The links between art, history, society

are clear in the outline you provide and

the opportunities to stimulate young people’s

interest and imagination are evident’.

Sir Nicholas Serota,

Chairman, Arts Council, England

Society makes art and art defines society’s culture

Little Dancer, aged 14, Degas, 1881

Metropolitan Museum, New York