ARTY

STORIES

Book 1

EGYPT – GREECE - ROME

Empires come & Empires go

Art and life

across the centuries

Ian Matsuda, FCA, BA (Hons)

for

Noko

Copyright 2017

Ian Matsuda, FCA, BA (Hons)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, transmitted or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher or licence holder https://www.artystories.org email: info@artystories.org

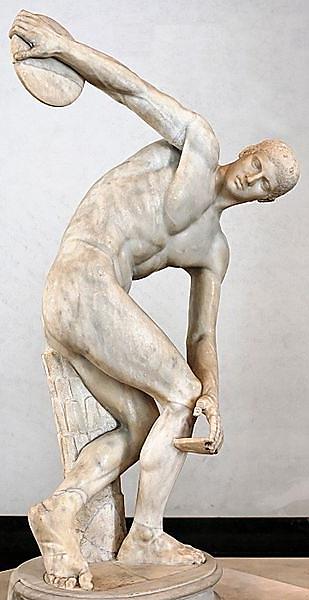

Cover: Discobolus of Myron, originally bronze in 450 BC, Roman copy, British Museum, London Queen Nefertiti, 1345 BC, Laocoon and his Sons, 200BC- 70AD, Greek trireme Warship, c.500BC

‘ARTY STORIES’

Art & Life across the centuries

‘Seeing people’s lives brings their art to life’

See the stories that made the art – the times – the place – the people BOOK 1: EGYPT – GREECE – ROME - Empires come and Empires go

A refreshingly entertaining introduction to the world of art through 5,000 years of tumultuous history This first book covers three great Empires that succeeded each other and forged the world we know today.

For thousands of years the Egyptians saw their world as a paradise that would continue after death. The Greek Empire revered natural beauty with cities full of colour, but their children were trained in war. The Roman Empire was founded on the blood of war, where slaves served the people while the Romans realised great art and architecture.

Ideal for student and art lover alike

Supported by the Arts Council, England as:

‘creative and engaging for young people’

‘the opportunities to stimulate interest and imagination are evident.’

Centuries of great art are a gift to us all

Books in this Series

Book 1 Egypt – Greece - Rome Empires come & Empires go 2 The Renaissance in Italy The Patron & The Artist 3 The Four Princes War, Terror & Religion 4 Northern Europe Revolution & Evolution 5 The American Dream Depression to Optimism

6 The Modern World The ‘…isms’ of Art

7 Past Voices Stories behind the Art All free e-book download

https://www.artystories.org

Book 1

EGYPT – GREECE - ROME

Empires come & Empires go

CONTENTS

• Ancient Egypt – a perfect paradise

• - Sculpture & Architecture

• Ancient Greece – Wars

• - Olympics

• - Philosophy & the Cosmos

• - A world of colour in cities

• - Alexander the Great - the Greek Empire

• The Roman Empire - Architecture

• - Paintings & Sculpture

• - Entertainment & The ‘Games’

• Summary

• Sources of information

Ancient Egypt – a perfect paradise

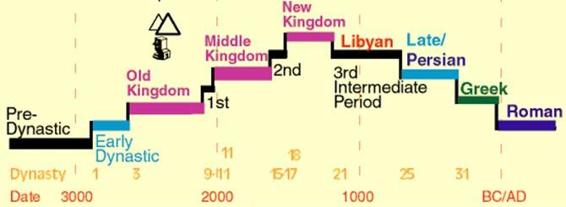

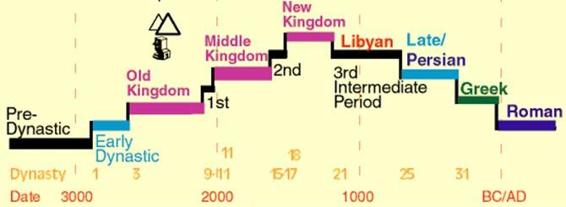

For an incredible 2,000 years the Egyptians saw their Empire and world as a perfect paradise and if they lived a good life, then in death they would pass to the same paradise. Unfortunately, their life meant that they would make an early trip to that paradise, but it was a good life, supported by a host of Gods.

Ancient Egypt was a land of remarkable

stability with 3 Kingdoms lasting up to 500

years each with short disruptions, after which

life would return to the normal ‘paradise’.

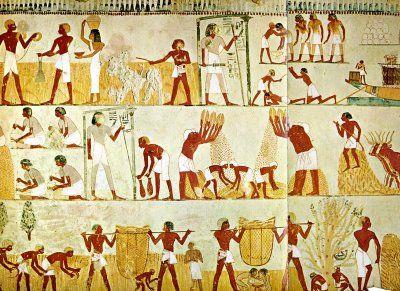

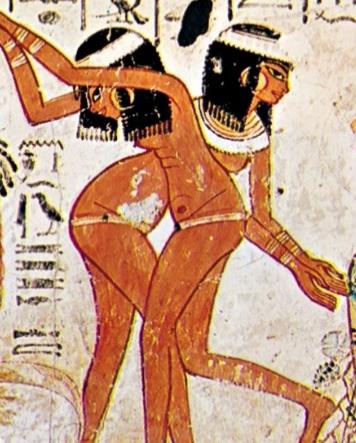

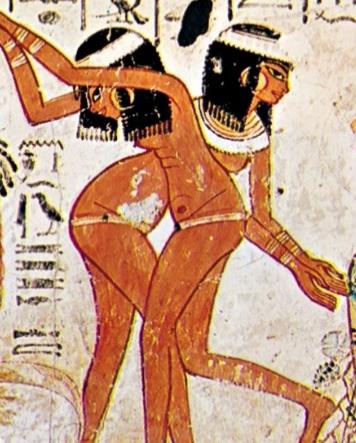

Their frescoes adhere to a strict religious and

cultural design, reflecting the unchanging

world both now and in the afterlife. Simple

lines and flat areas of colour create a sense of

order and balance within a composition.

An order and balance fundamental to Egyptian culture, in a structured society unchanged over 2,000 years. (1) Their pharaohs were seen as gods and could direct thousands to build monuments and form great armies.

But the Egyptians believed that they lived the best possible life in the best possible of worlds, before and after death. The philosophy was one of living in harmony and in balance with both the community and the world at large. A line from the First Kingdom reads:

Let your face shine during the time that you live.

It is the kindness of a man that is remembered

during the years that follow

This philosophy applied to all social classes, where all valued life and enjoyed competing in ‘Games’. Board games and sports were both popular pastimes and the ‘games’ were often combined with festivals and national celebrations. Field hockey, rowing, javelin, archery, athletics and the chariots used in war, all competed. Even the Pharaoh was required to prove his fitness by running a measured course - some after 30 years of reign!

Fitness was important and weekly routines were designed to encourage not just stamina, but team spirit and so social bonding. This healthy life was reflected in cleanliness both in their homes and personally where all bathed regularly, with men shaving their heads and body hair to avoid lice.

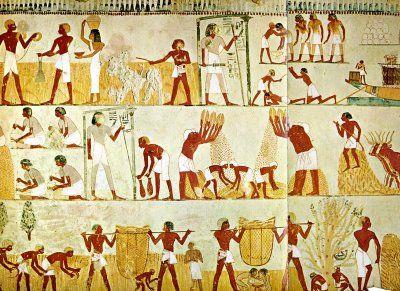

The vast majority were farmers who worked the fields for the

state or landowning local nobles, taking a portion of the

cereals for themselves. This was supplemented by growing

vegetables alongside their homes and supplemented by

fishing, but regulated by the state. So, all Egyptians enjoyed a

vegetarian diet, supplemented by some poultry and fish,

particularly on festival days. The Egyptians believed that

humans, animals and plants were one of a whole and an

essential element of the ‘cosmic order’.

An agricultural and environmental system which many people

advocate today.

Tomb relief of ploughing, harvesting and threshing.

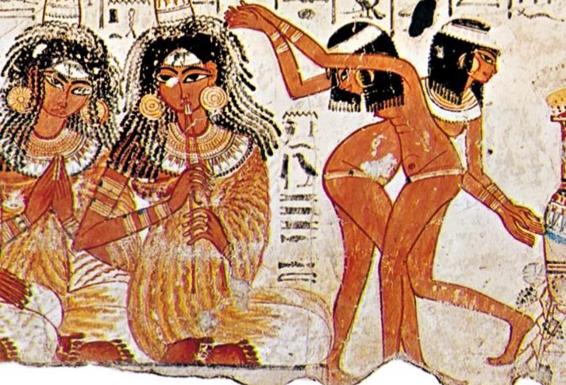

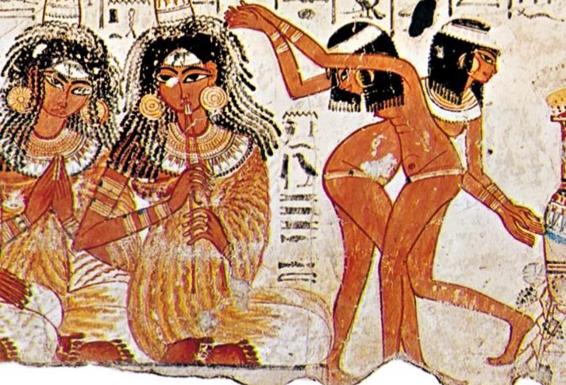

Women had total equality in owning a business or land and initiating divorce. While men laboured in the field, women ran the home,

including the vegetable plot and making the bread and a honeyed beer

– essential staples of people’s lives. The Nile was not clean enough to drink, so a low alcohol beer was consumed by all and ‘inns’ were in every community. People enjoyed their social lives and feasts and festivals were accompanied by music and dance. (2)

Children had pets and toys including puppets, dolls and mobile wooden toys. Storytelling of magic, romance and ghosts provided their history. Children ran naked until the age of puberty - at 13 for girls and 15 for boys, when they would normally marry. People wore short linen ‘kilts’ that were difficult to dye so most were left in their natural off-white colour and all went barefoot. The Egyptians loved their oils and perfumes.

The streets rang with people and traders shouting, with smells of cooking overhung with burning incense, whilst in the house toilets were a hole in the ground covered by sand.

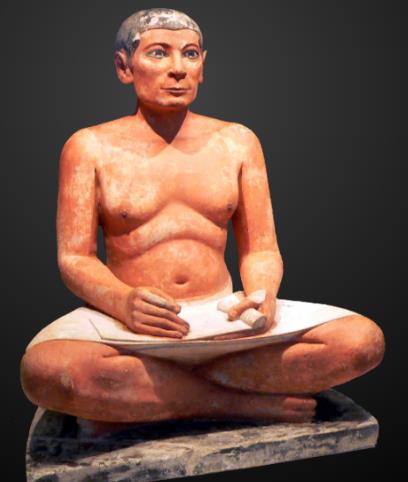

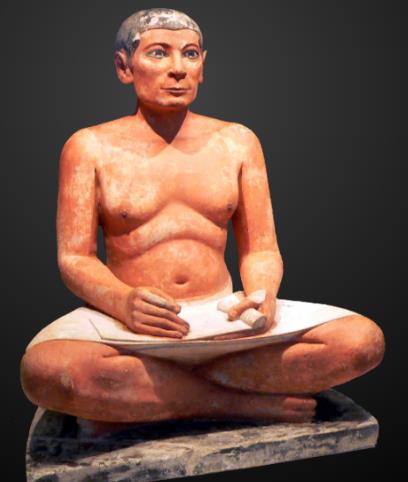

This society ran without coinage, but under a barter system where fixed amounts of agricultural produce could be exchanged into copper, silver or gold. A system that was standardised across Egypt and so which resisted any monetary collapse or inflation. The transactions were open to all, but supervised by ‘scribes’ who held a respected position in the administrative and legal bodies, in an all-encompassing state.

The Seated scribe, Saqqara

Rather than applying written legal statutes, disputes were settled on a commonsense view of right and wrong.

Punishment was swift and all swore an oath to speak the truth.

The Pharaohs were largely benevolent, ruling over a prosperous land, but inevitably some pharaohs were blood thirsty. Tearing through their own families with poisons and strangulation and wreaking dreadful vengeance in battle, ripping into prisoners or into slavery, although allowing them to work and buy themselves out of slavery.

In the long times of peace, a perfect life had one underlying fault. With the Nile running at the centre of this tropical country at the north of Africa, disease from parasites such as malaria and worms, threatened all those who worked and played outside. One third of children would die, with their father dying around age 30 and their mother at 35. People died young, although with an unshakeable faith in an afterlife. Perhaps surprisingly the population grew from 850,000 to 4-5 million, as the empire grew in power.

With a life spent pampered indoors the Upper classes lived longer, anywhere from age 60 up to 90, ironically providing the ruling stability in Egyptian society. This long living upper class (3) could take a longer view and undertake monumental buildings, which are astonishing in the remarkable skill and techniques used by artisans.

Ancient Egypt, Sculpture & Architecture

This sculpture of Pharaoh Khafre was one of 13 that stood in a huge pillared necropolis (funerary city) and is carved from an extremely hard and dark stone, related to diorite. To carve and then polish this stone with only a bronze tool and then grind and polish the surface, is a remarkable achievement, particularly in the symmetry and ideal body proportions. His strong face suppresses all motion to create an eternal stillness, continuing in a world after death. He is portrayed as a benevolent God in the universe where all Egyptians lived, underlining the unchanging nature of life which encompassed all living things. Here the God Horus is depicted as a falcon, spreading its wings across his shoulders, protecting the Pharaoh.

Khafre, enthroned, 2570 BC, Egyptian Museum, Cairo

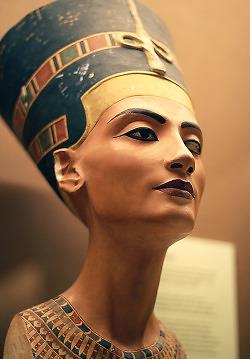

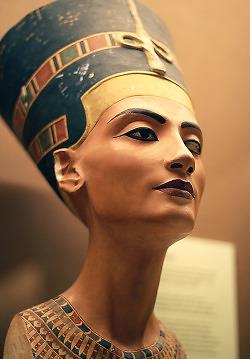

The life size bust of Nefertiti also portrays a timeless beauty that will continue into the afterlife and is still with us today, 3300 years later. The bust shows a symmetry in the lines of the wide hat continuing through the forehead, down to the chin and poised on the delicate neck, much as a flower stem. Nefertiti displays a protective kindness and authority with her chin held high. This beauty and the realism achieved are in direct contrast to the religious confines of the unchanging temple frescoes.

Egypt abounds with a sense of order and a power that is unchallenged, displayed in the architectural order of the King’s tomb (pyramid) on the Giza plateau, adjacent to Cairo.

Bust of Nefertiti, 1345BC, Great Royal Wife on the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten. Neues Museum, Berlin

The Giza pyramids were built 4,600 years ago to such mathematical precision, that at 139m high, each base is equal to an error of just 58mm with joints of 0.5mm between each of the 2.9 million two-ton blocks. Even over 20 years of building, one would be set every 10

minutes, following a production line of quarrying, shipment and

precision cutting. The exterior was clad in highly polished white limestone panels and possibly with a gold capstone. This Egyptian order and precision is very sophisticated, where at the same time Northern Europe was building the crude Stonehenge.

Pyramids of Giza, 2589-2504 BC, Pharaoh Khufu

Built over some 20 years by between 30-50,000 mostly volunteer farmers during the annual flooding of the Nile.

To work on any Pharaoh’s tomb or temple, was considered an honour. Some 10% were workers and artisans, enjoying privileged conditions in an adjacent village. After Giza, pyramids were much smaller and later pharaohs were buried in underground tombs in the Valley of Kings, hiding burial sites from later tomb raiders.

Great temple complexes were built to

house a Treasury in a series of tombs,

dominated by a temple that hid an

underground maze of chambers and

passages. 20-ton trapdoors were designed

to protect tombs and confuse and trap any

prospective robber. Historical records tell

of a fabled lost networks of 200 rooms, yet

to be uncovered. Egypt was a glorious

kaleidoscope of brightly painted buildings –

temples and peoples’ homes. The carved

columns represented bundles of reeds and

lotus flowers.

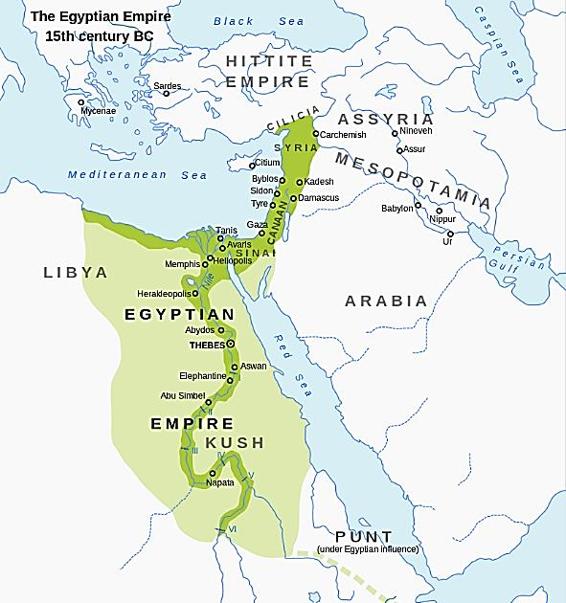

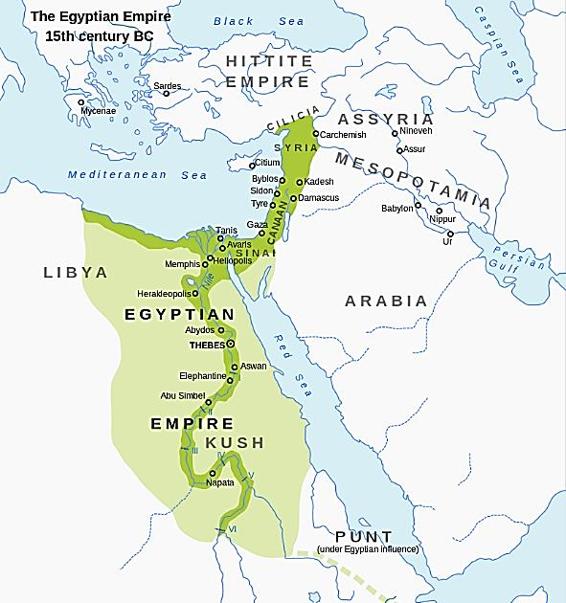

Although trading throughout the Eastern Mediterranean, the Egyptian people were not great travellers, regarding other lands as inferior to their

‘universe’. They traded across the Mediterranean with 43 metre ships, exporting grain and linen and bringing back spices, oil and luxury goods, with ebony gold and ivory from ‘Punt’, East Africa. Their military was primarily for defensive purposes and only extended their empire when threatened by adjacent countries, North and South. But the Egyptian Empire was to eventually decline and be taken over first by the Persians from Arabia, then the Greeks, to be finally absorbed into the Roman Empire. Egypt, extent of Empire, 1570 - 1069BC

Art had underpinned Egyptian society by projecting an unchanging and secure, life in which everybody was part, in an all-encompassing bureaucracy guided by a ruling Pharaoh. Art told their story and was a visible depiction of their culture and beliefs. The Greeks in particular, frequently visited and took home the architectural temple designs, still used worldwide today.

Ancient Greece – Wars

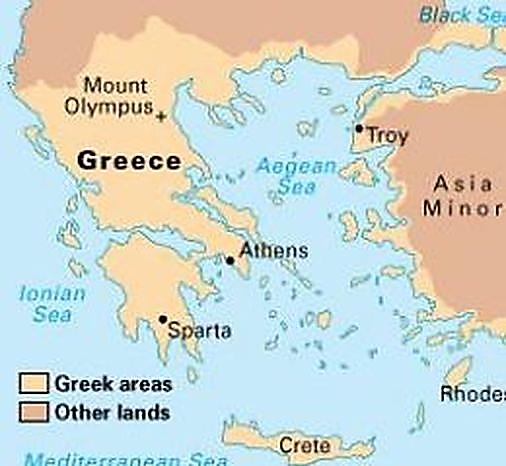

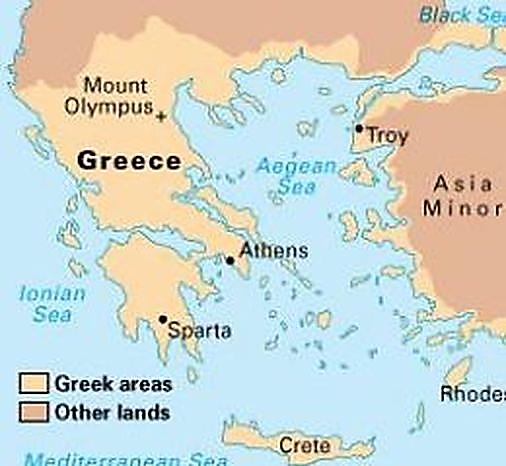

Ancient Greece, land of Gods and wars. For an incredible thousand years, war and peace swept across the lands and seas between Sparta, Athens and Troy until finally facing the might of the Persian Empire. Their world was a mixture of peace and turmoil, of victory and defeat, where the Gods again held sway.

Life was dominated by the Greeks’ belief in their Gods overseeing and rewarding their lives, although they did not share the Ancient Egyptian belief in a continued paradise after death. Gods were fundamental to religious culture and life, but it was a male dominated society.

For 500 years the individual city states of Sparta, Athens and Troy fought on land and sea. Greece was a place both of beauty and

brutality. Children in Sparta, both rich and poor, were trained for war from the age of seven and later required to serve in the army. Each state was afraid that the other would become too strong and then by monopolising resources, overpower all the states around. During one siege the Spartan warriors were massed at the gates of Athens, but they were never to enter. States depended on their harvest to feed their citizens and most people worked in the fields. The warriors were also farmers and had to return home for the harvest!

But threats also came from across the sea where the great Persian Empire in Asia Minor, was massed at the doors and set to invade.

Classical Greece was not to emerge until the Persian threat had been overturned and it would take two great battles for that to happen. Persia invaded in 480BC at the Battle of Marathon where 10,000 Athenians faced some 20,000 Persians and a Persian fleet of 600 ‘triremes’ (galleys) with transport ships for soldiers, horses and provisions.

Great battles at sea would see 170 oarsmen in each

galley, smash and crash their great pointed bows into

the enemy. On land, their armies would line up to face

each other and charge to crash with their shields. Then

tear into each other with long spears, using short

swords to cut and slash when the spears broke. These

were fierce and bloody hand to hand battles.

Although outnumbered 2:1 the Athenians triumphed, surrounding and destroying the Persian army soon after their landing on the beach. Persia’s empire was dealt a mighty blow with a loss of 6,400 men against just 192

Athenians. The runner Phillippides ran the famous 25 miles from Marathon to Athens to announce the victory and with his very last breath exclaimed ‘Joy, we win’ and the legend of the Olympic marathon was born.

10 years later a unified Spartan and Athenian army

faced a second even larger Persian force of 100-

150,000, facing just 7,000 Greeks. But superior Greek

strategy drew the Persian army into a narrow pass

between cliffs and the sea, squeezing the Persians

against a Greek wall of bronze shields. They resisted

for 3 days, until - with the dead piled so high, the

Persians had to clamber over - just 300 Spartans and

700 Athenians were surrounded by the Persian army in

a brave, but futile defence.

Finally beaten, Athens was evacuated and then burned to the ground. But at sea the Greeks had simultaneously trapped and decimated the larger Persian fleet, again by luring them into a narrow strait, cutting off their escape home. With the bulk of their 3,000 transport ships destroyed, the Persian army withdrew on a long overland march home, where most were lost to disease and starvation. Persia never again regained it’s strength. (4) This great victory left the Greek states to dominate the Eastern Mediteranean, bringing huge trade and great wealth to its people, leading to the unified Empire formed by Alexander the Great. This strength formed the seeds for classical Greece, bringing democracy and the great art and a culture that we still admire to this day.

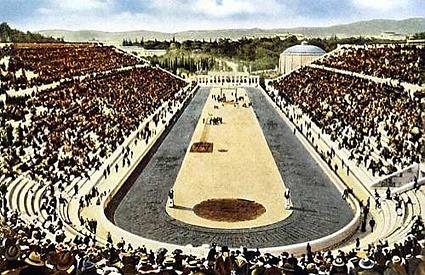

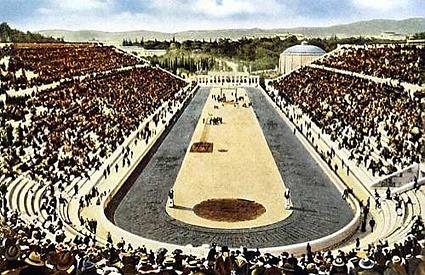

Ancient Greece - The Olympics

Amazingly there was one thing that would stop all wars – the Olympics! Winning at the Olympic Games was as important as it is today, bringing great fame and prestige and wealth to the athlete, to his home city and to his state. The greatest games of the ancient world. But to enter each state had to sign a truce that no wars would be fought during the ‘Games’ – sport wins over war! Their dominance was then asserted through sport.

Competitors came from near and far with some making a long journey, including a 2-day boat voyage from the islands and lands around the mainland. In those days, this could be a dangerous voyage with storms driving the boats on to rocks and many drowning.

On arrival the stadium stretched before them, high up in a

ravine, in the hills north of Sparta. Under clear blue skies, a

white oval with tiers of seats for 50,000 people from across

all the states. A sea of white robes, all cheering and singing.

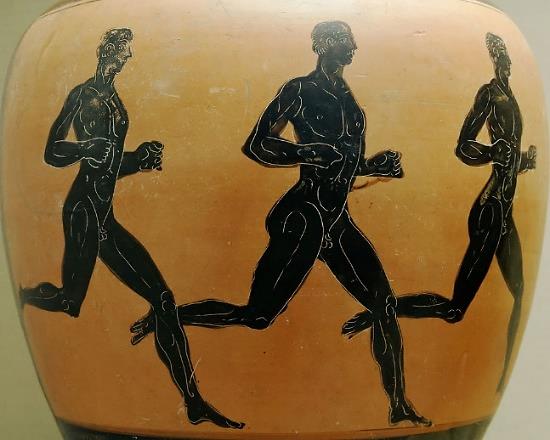

The athletes would line up to enter the arena, each naked

and glistening with olive oil rubbed in to their skin to display

their muscles. (Women were banned from the stadium, to

have their own games.) Striding down the entrance steps,

through a line of polished life-size bronze statues, shining

and celebrating past champions, they would parade around

the arena, as each state cheered their champion. (5)

With the games so important, cheating was banned, as with doping today. Any athlete found cheating would have his name published and shown at the entrance, to the great shame of both himself and of his state. This reinforced the bonds in society and the cultural values of honour and loyalty.

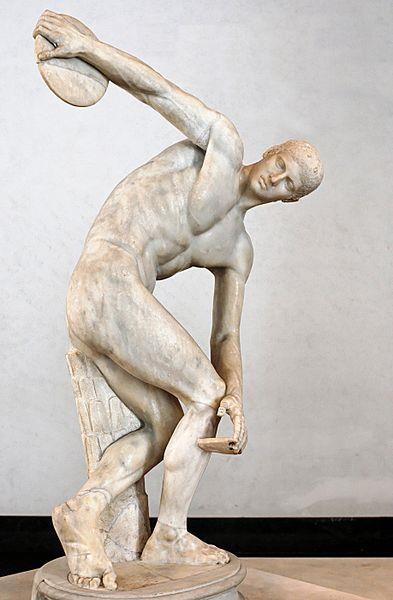

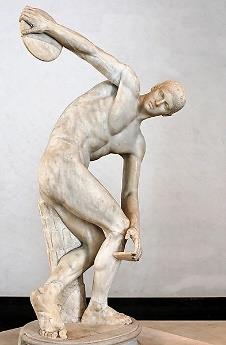

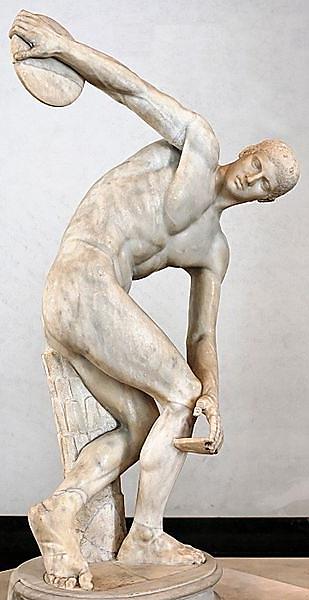

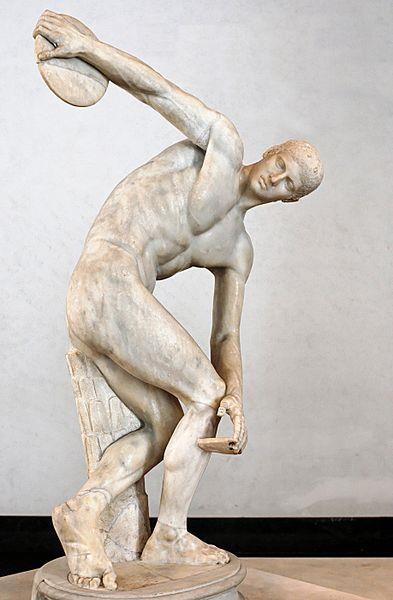

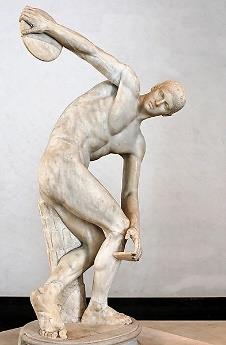

One event was the discus and that can still be seen in one of the statues commemorating a past champion. Today that bronze statue has long

gone, but the Romans had made a marble copy known as ‘Discobolus’ –

the ‘Discus Thrower’.

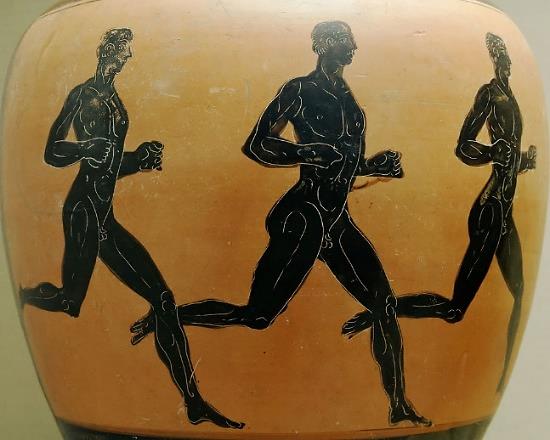

A major aspect of the Olympics was artistic

expression, where Greeks described these

athletes as ‘beautiful’ and admired their

strength and elegance, reflecting their

‘ideal’ culture. Like today their fame was

celebrated on vases and jugs where their

balance is artistically portrayed

Discobolus, originally bronze in 450 BC,

Roman copy, British Museum, London

The Games ran for 1,000 years from 765BC to 385AD and grew to some 50 events of running, jumping, javelin, boxing and wrestling, soldiers in heavy bronze armour running two laps, and the famous chariot races. In the long jump competitors swung two weights in front of themselves, to throw their arms and body further forward. (5)

All the Greek city states shared a winged goddess of victory called ‘Nike’ who stood at the entrance to the Games.

Now we have running shoes made by ‘Nike’ using the same wing:

Winged Nike, c. 200 BC, Louvre Paris

Philosophy and the Cosmos

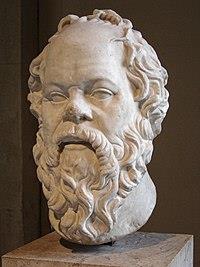

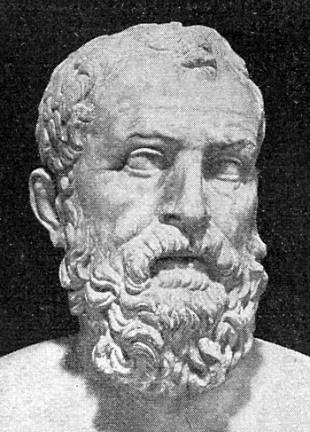

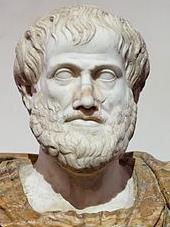

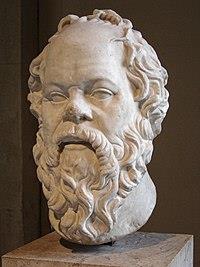

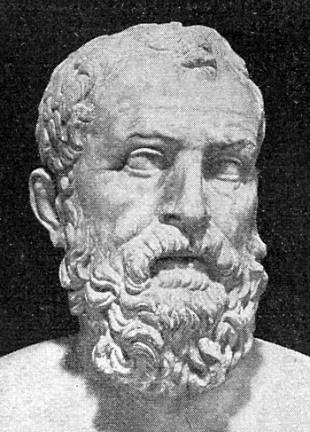

Underlying Greek society was the preoccupation with philosophy (meaning a ‘love of wisdom’), that questioned the nature of the world around them and the individual ethics that lead to the best way to live. This freedom of thought and expression gave life to the democracy (meaning ‘people power’) that formed the political and civic institutions, setting the purpose of politics with equal justice for all. Our world today owes much to the philosophers who led these discussions, of which three made the greatest and most lasting contributions. (6) Socrates (470-399 BC) who introduced a form of inquiry where groups of individuals were led through question after question of themselves to realise a clarity of thought, questioning their statements through reasoning and logic, to arrive at an informed proposal and so conclusion.

His student Plato (427-347 BC) raised ethical questions as to what is a fulfilling life in an ever-changing world, where everything can so easily be taken away. He questioned the sense of permanence that we experience within a reality of change. This separation of the mental realm from the pains and changes of the physical world, can lead to lasting values away from material concerns. Plato established the Academy of Athens, the first institution of learning in the western world, lasting almost 1,000 years.

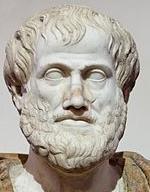

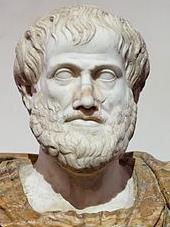

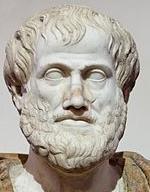

Then Plato’s student, Aristotle (384-322 BC) sought to

better understand the physical world and how matter is

inter-related in different forms. His theory was that

substances determined forms, whilst Plato considered

that forms determined their substances. For Aristotle

‘substances’; or ‘matter’; are unchanged, whilst the forms

they compile, can evolve. But what comprises ‘matter’?

Other Greek philosophers proposed that matter was comprised of atoms that can neither be created nor destroyed. Collisions of these atoms formed a cosmos consisting of many different worlds, which is infinite and that within this, the earth rotated around the sun. Not a million miles from our discoveries today and without the benefit of telescopes or calculators! ‘Ancient Greece’ was a sophisticated, confident, and intellectual society.

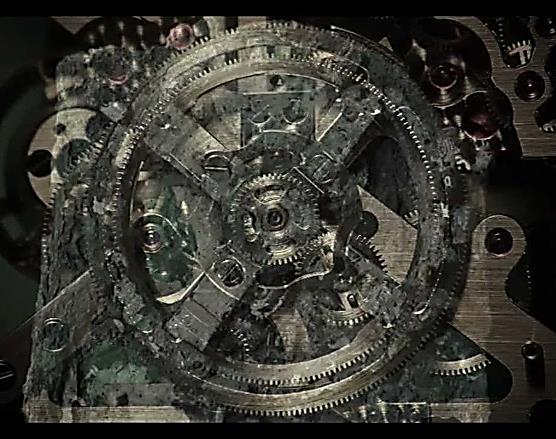

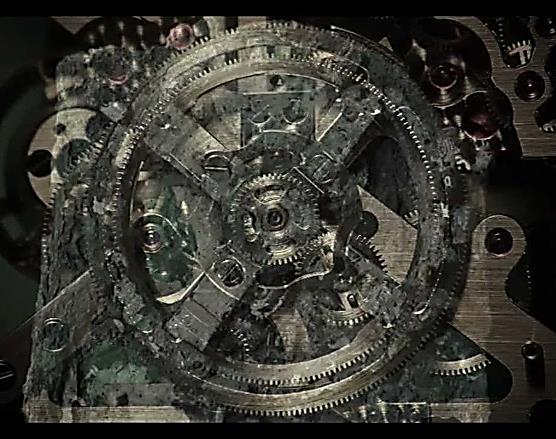

Greek society valued education with a curriculum of arithmetic, sports, and music.

Science was also taught and the Greeks developed an early form of an analogue astronomical computer, discovered in an ancient shipwreck, whose complexity and invention was not matched until the 16th & 18th centuries. This device was used to predict astronomical movements and so provide an accurate reading of the stars as a calendar for religious events, decades in advance. That the earth is a sphere was recognised and its diameter calculated to within an accuracy of 5%.

Antikythera Mechanism, National Archaeological Museum, Athens

A world of colour in cities

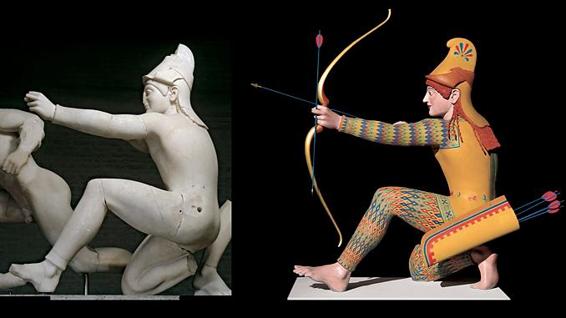

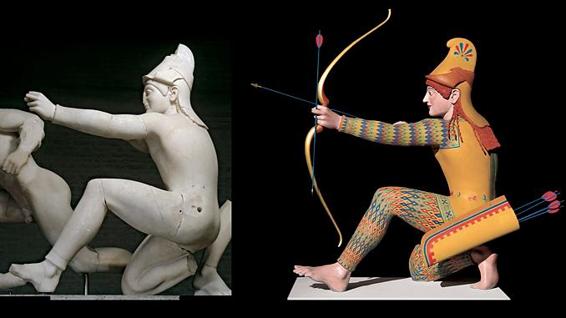

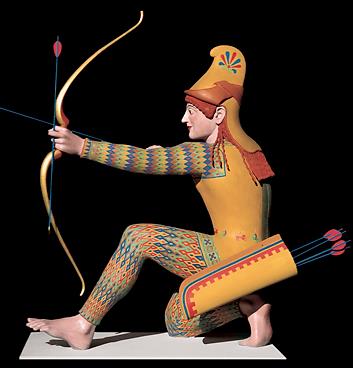

As with Egypt, the ancient Greek world was full of colour, on buildings and sculptures. Most sculptures were made in bronze or in clay terracotta and then painted in bright colours, but the colours have long since worn off.

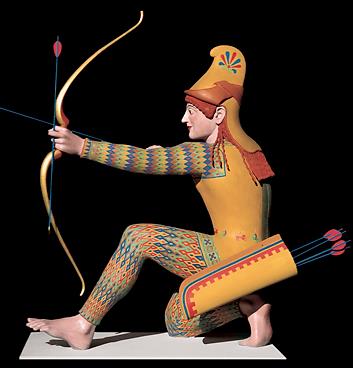

This statue of ‘The Archer’ compares with the faded

colours today, with how it could have looked when

painted, alive and vibrant. Colour ran throughout the

city, fostering a great pride in the citizens for their

society and for its culture. A pride and loyalty to

support and defend the state.

A Trojan archer, Temple of Aphaia, c. 490BC. Sackler Museum,

Harvard, USA. Vinzenz Brinkmann & Ulrike Kohn-Brinkmann

The temple of the Parthenon stands in ruins today high up on a hill in the centre of Athens, but was very different when originally painted.

The Parthenon, Athens, illustration of possible original colours

The temple strongly resembles the Ancient Egyptian multi-pillared temples and like them was used as a Treasury. The frieze allows for an angled roof and when painted, brings the figures to life where otherwise high up, they would be difficult to see. The classic style of the Parthenon has been replicated over centuries and remains to this day a statement of wealth, power and culture - used by banks and government buildings.

Dominating and looking down on the city of Athens, the temple was designed to bring a pride to the Athenians and gave rise to a high culture of art, philosophy and democracy. The temple held a colossal 35m statue of the goddess Athena. Brightly painted and adorned with gold and ivory, the statue towered over the interior. She represented a host of qualities from wisdom, law and the arts through to strategic warfare, heralding Alexander.

For an informative animation and depiction of Athens at this time, go to: https://www.greece-is.com/assassins-creed-odyssey-stuns-incredible-recreation-ancient-athens/

Ancient Greece, Alexander the Great - the Greek empire

Alexander the Great was the most famous Greek warrior and was the first King to rule all of Greece in 336BC

and lead to a great new Empire. But as a shooting star, his glory and reign were to be tragically short lived.

Rising to the throne at just 20, he brought the

states together as one Greek empire. In just 4

years he conquered most of the countries

around the Mediterranean and the Middle East.

In deadly battles he swept across nations,

including the Persians and was welcomed as a

saviour into Egypt. By 27 he had fought and

won against overwhelming odds, to rule over 3

continents as far as India, founding 70 cities,

but then dying of a fever aged just 33. (7)

Battle with Persia, 331 BC. Mosaic from Pompeii, c. 100BC

After the Emperor Alexander died in 323BC, his empire fell back into fighting between the city states. From being united, each state now looked to defend itself, rather than to act together as one nation. This allowed the Romans to invade each of them in turn and conquer the Greek states one by one until - by some 200 years later in 146BC - they had ransacked the last major Greek city of Corinth, 50 miles west of Athens. This was a dreadful battle where the Romans put the entire male population to the sword and sold all the women and children into slavery. Then a custom of all Emperors.

Alexander the Great, Roman copy, original bust 3rd Century BC

Rome went on to overcome the North African and Spanish empire of Carthage, heralding the Roman Empire.

The Roman Empire

Rome now dominated the Mediterranean and so as the

Greek empire collapsed, another Roman rule sprung up. As

the Roman Empire became bigger and stronger, they swept

even farther across all of Europe from Egypt to England,

defeating all the armies in their path.

This sprawling Empire needed transport and the Roman

network of roads, rivers and sea was comparable to those

of 18th C Europe – 2,000 years later. Trade between the

provinces was needed to supply the huge occupying

armies, which consumed 70% of state expenditure.

The Roman Empire 150 AD

With these demands there was a central control of trading with a state merchant fleet, through which the majority of grain was imported from North Africa. Specialities such as oil and wine came from Spain and Greece to supplement local supplies. This trade was financed by bankers and facilitated by the early use of coinage, calculated on the beads of the Abacus, which remains in use today. A transport and financial structure that supported the Roman Empire for centuries. An empire supported by captured slaves, in work and in the huge armies, with slaves comprising up to 5-10 million of the Empire’s total population of 50 million across Europe.

Slaves were part of the family, many gaining their freedom, marrying their master or having their children.

The Romans looked to project this power and superiority through their own great cities with an art that drew on ancient Greece, providing a unifying Roman culture from East to West. (8)

Architecture

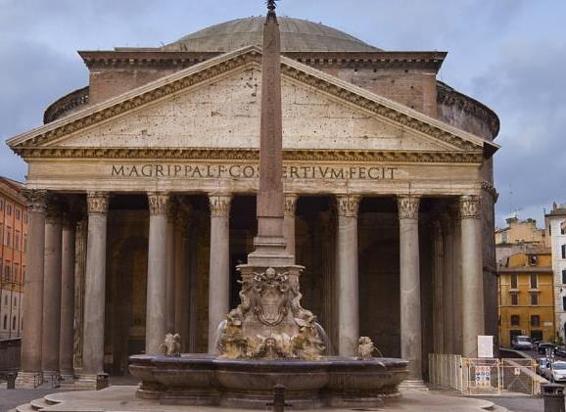

Throughout their empire the Romans built splendid cities to rival and exceed those of Greece. The greatest of these was Rome.

The capital of the Roman Empire and then the largest and most

sophisticated city in the world. Where the Greeks were master

sculptors, the Romans were master engineers and in their great

public buildings and temples they adopted the Greek style of

architecture, complete with the columns of the Parthenon.

Illustration of how the ancient Roman Senate may have looked

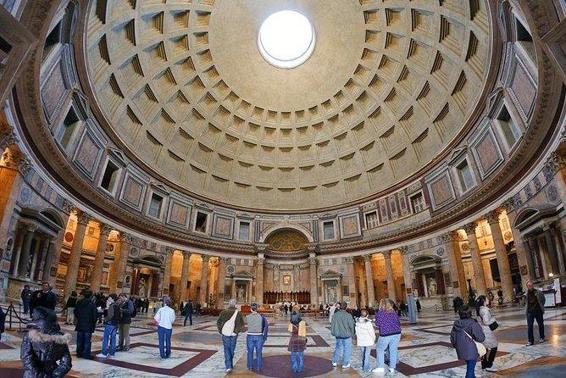

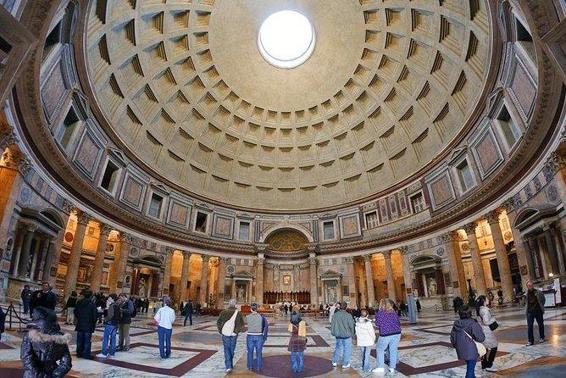

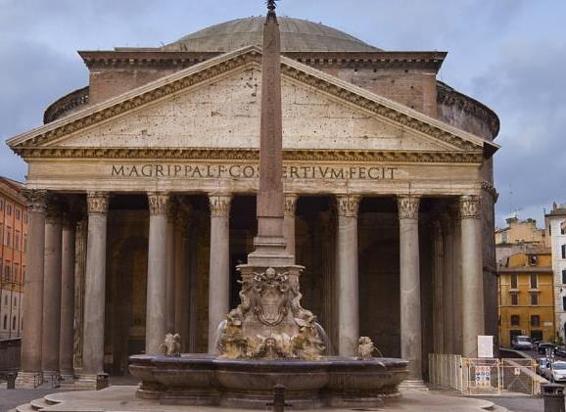

Much of the Romans’ building technology in the use of concrete still remains a mystery, where some buildings such as the Pantheon

temple, still stand after 2000 years and is still the world’s largest unreinforced concrete dome.

The dome diameter and

height are both equal at 43

metres and the Corinthian

columns and frieze at the

front, are borrowed directly

from Ancient Greece.

The Pantheon, built in 126AD

External Corinthian columns and frieze

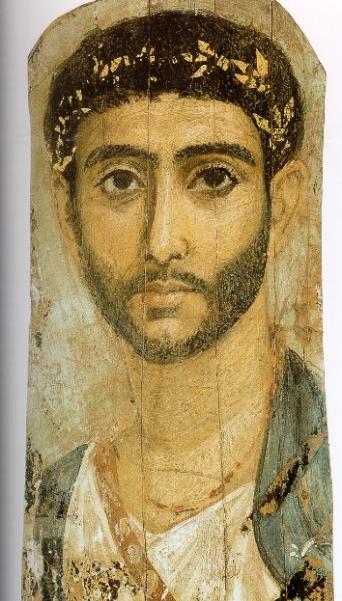

Paintings and sculpture

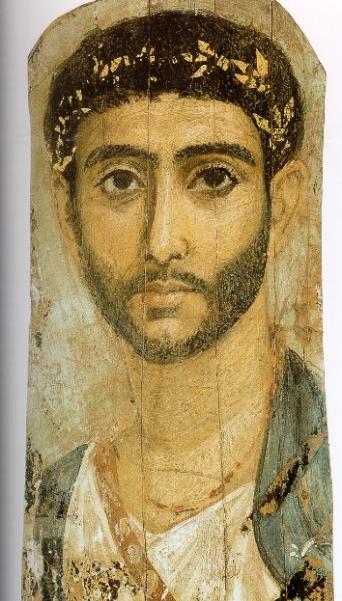

Paintings are largely confined to frescoes in private villas and so have suffered decline over the years. But one unique source of the artists’ skill is found in portraits buried with their owners’ coffins to represent their face in life.

Painted on wood, they were originally folded into the bands of cloth used to wrap the bodies. The naturalism and use of light and shade demonstrate a high level of skill, that was to be rediscovered more than a thousand years later in the Renaissance. (Book 2)

Mummy portraits, Roman-Egypt, 1st – 3rd century AD

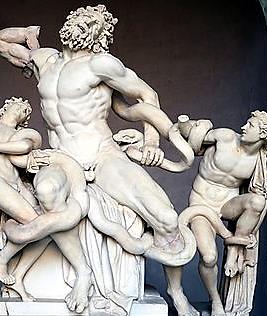

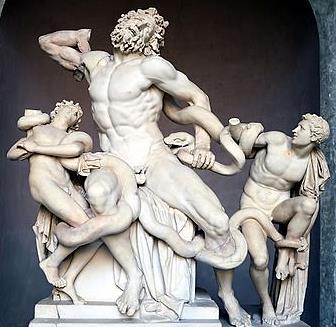

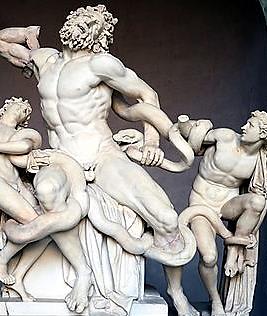

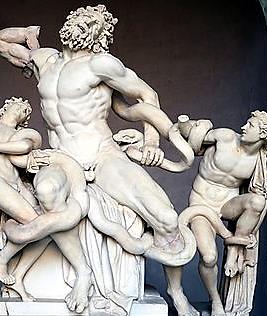

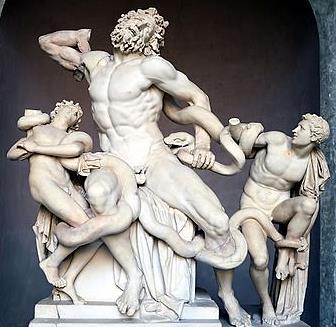

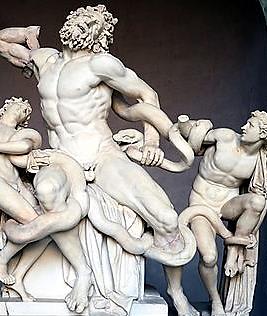

Sculptures drew on Ancient Greece and were plentiful. This statue tells the story of a Greek priest, Laocoon. He tried to warn the

defenders of Troy that the Athenians were planning to hide soldiers inside a gift of a giant wooden horse. Having battled over a fruitless 10-year siege, this offering persuaded the Trojans to ignore

Laocoon and to finally open the gates, allowing the army of Athens to burst into the city. For his attempted betrayal of the victorious Athenians, Laocoon was punished with serpents that killed his two sons, but not Laocoon who was left to grieve alone.

The sculpture depicts the strength of the State, overcoming all

traitors and enemies to suffer at their hands.

This realism and vitality was to inspire the Renaissance, where

sculpture was also used to influence society as to the power and

authority of the state. (Book 2) Laocoon and his Sons, 200BC-70AD, Vatican Museum

Entertainment & the ‘Games’

Entertainment and religion were both seen as maintaining a social order. In an empire of power and hedonism with entertainment night and day, Rome was packed with bars and brothels. This was a society based on one third of slaves serving their privileged masters, with lesser citizens packed into slums of 8 storey apartment blocks. An urban population of between 1.0 and 3.6 million, required an endless supply of food from the surrounding network of farms owned by the upper class and again worked by slaves. (9) The streets were heavy with the smell of urine and excrement, where Roman bottoms public toilets sat in rows. The air was heavy with rancid meat and fish stalls, all laced with perfumes for personal hygiene. Rome was a dirty, dangerous place.

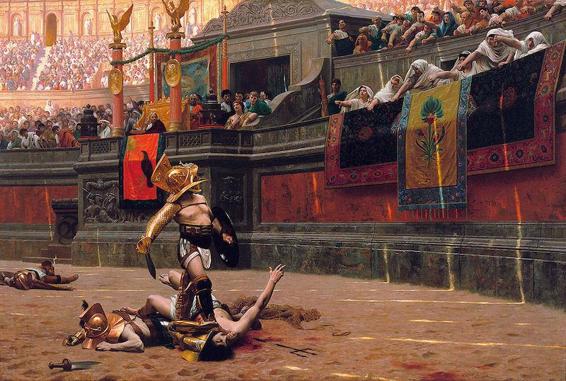

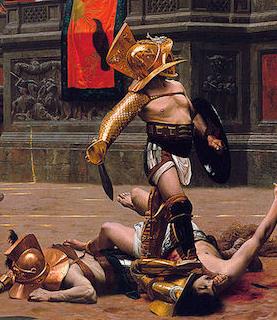

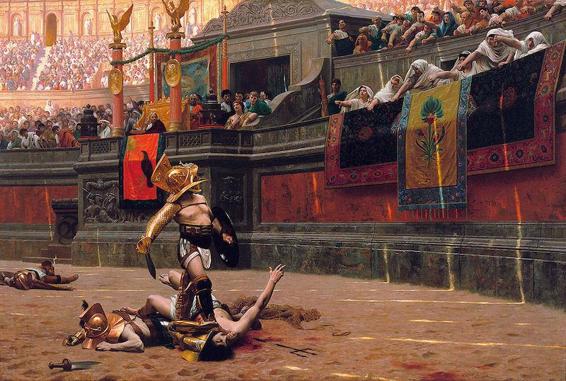

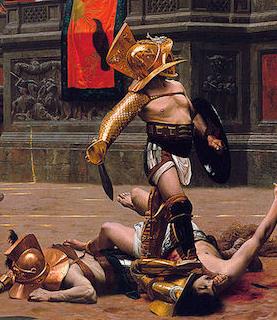

This Roman Empire was based on war where triumphs in

battle were celebrated in the bloody battles enacted in the

Colosseum in Rome for over 390 years, in their version of

the ‘Games’. Up to 60,000 spectators would witness land

and mock sea battles and chariot races. Additionally, trained

gladiators would fight to the death and religious martyrs

would be thrown to the lions. In all some 400,000 people

and a million animals were to be slaughtered. (10)

Their fate as to whether they should live or die, was in the

hands of the crowd, with a ‘thumbs up’ or ‘thumbs down’.

They cheered each brutal and bloody death.

Sports of running, swimming, wrestling and hockey were

played by youths on ground outside of the stadium. Pollice Verso (turned thumb) 1872

Jean-Leon Gerome, Phoenix Art Gallery

Some 230 of these amphitheatres were built in cities across the empire to both entertain the citizens and to establish the all-powerful Roman Imperial superiority.

The Romans had attributed their great success to their many Gods, with prayers forming a mutual contract with the Gods: ‘I give that you might give’. They allowed local religious beliefs to continue throughout the conquered lands. But when the Emperor Constantine sought to secure his declining power in 312AD, he chose to conduct his political propaganda through Christianity, with just one God and one Emperor. Christianity spread throughout the Empire with its centre in Rome, but a Rome soon to fall.

In the Roman Empire, as in Greece before, the states eventually fell into fighting between themselves and between the east and west of the Roman empire, causing the Empire to divide in 395AD.

By the 5th century the western empire of Rome had grown weaker allowing the armies of the Visigoths; who they called ‘Barbarians’; to sweep down from the northern plains of Germany. In 410AD they ransacked Rome, taking its treasures and destroying its great buildings. Across Europe the Western Roman Empire was lost.

Soon, with the power of the Caesars gone, the people left Rome and the city crumbled, leaving the wind to blow through the ruins of the once grand buildings and much of the art and culture was lost for centuries.

The eastern empire with its capital in Constantinople - named after its first Emperor Constantine - was to last for a further thousand years until the Ottomans (from today’s Turkey) conquered the city in 1453. (It was renamed Istanbul in 1923.) The Ottomans went on to wage wars across Europe for some 200 years as wars between Kings and Emperors – The Four Princes - swept across Europe during the Reformation. (11) (see Book 3) The loss of these great empires meant the loss of their societies – how people lived, worked and their great art.

Slowly, over decades this cultural life declined or was destroyed in wars. In states like Florence the people now lived poor lives in dark wooden houses. So far from the grace of the splendid buildings of ancient Rome.

In Book 2, we look to the re-birth; or the ‘Renaissance’; of this culture, but only after a thousand years!

Summary

In Ancient Egypt there was a deliberately unchanging culture and society over 3,000 years.

People lived in harmony with their world in the sure and certain belief that the after-life would continue this paradise. But for the common man, with disease and parasites primarily from the Nile, life expectancy was short and so his belief was important in maintaining a bureaucratic social order, under a panoply of benevolent Gods.

This unchanging world is reflected in the unchanging religious art, making the past as recognisable as the present, reflecting the certainty of their world and their future paradise.

A ruling class had greater longevity and built monumental temples and tombs to both their power and glory and to society’s culture of an unchanging and perfect world.

These sculptures display a beauty and a natural realism, sculpted from both hard rock and in painted terracotta. They exhibit a stillness as if looking out over the centuries and to the paradise beyond, protecting and guiding the people to paradise.

The succeeding Greek Empire had waged wars internally

for centuries, before coming together against a mighty

Persian Empire, where their unified strategy overcame

far superior forces and drove them from the

Mediterranean. Greece could now dominate trade and

prosper to realise a democratic and sophisticated society

Then to the hills of ancient Greece with the Olympic Games and how they even caused the Spartan wars to pause. Even between enemies, competition was strong but fair and all athletes were admired for their physical beauty. The importance of these Games in the Eastern Mediterranean caused them to survive for 1,000 years.

This competition, national pride and values still resonate in today’s Olympics.

Philosophers in Ancient Greece looked at the nature of life and of their own lives as to how they could live in the best and happiest society. Citizens were encouraged to consider a range of subjects from politics and ethics, to the study of nature and their place in the cosmos.

This freedom of thought and discussion was to lead to the democracy that we enjoy today.

Then the colour that the Greeks brought into their sculptures and buildings, bringing civic pride and art into all their lives. Athens became the sophisticated centre of culture where all citizens contributed in a democracy that we enjoy today.

A realism in art was important and was to be re-introduced more than a thousand years later, in the ‘Renaissance’. (see Book 2)

Then the Emperor Alexander the Great, unified the states and built a great Greek Empire across Europe and Asia, founding 70 cities in just 13 conquering years.

Then with his early death, it all fell apart, to separate and for themselves to become vulnerable, to be conquered by the new Roman Empire.

The Romans were master builders and some of their techniques with concrete construction are unmatched today. They inherited bronze and terracotta sculpture from the Ancient Greeks and copied these in long lasting marble, preserving them and taking all their realism and vitality into their own sculptures, to be rediscovered in the Italian ‘renaissance’.

A Roman life was full of active and self-indulgent pleasure, where the amphitheatres staged regular and bloody battles – termed ‘The Games’ - where the spectators decided the killing.

This life was supported by millions of slaves in an Empire that was to fall into division and destruction as a once an all-powerful Empire was lost. Conquered states rebelled and the wealth went with them. Rome was bankrupt and fell into decay and ruin.

Sources of information

(1) https://www.ancient.eu/article/933/daily-life-in-ancient-egypt/

(2) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egypt

(3) https://www.ancient.eu/article/483/ancient-greek-society/

(4) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greco-Persian_Wars

(5) https://www.olympic.org/ancient-olympic-games/the-sports-events

(6) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greek_philosophy

(7) https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-history/alexander-the-great

(8) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Roman_Empires

(9) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culture_of_ancient_Rome

(10) https://www.history.com/news/10-things-you-may-not-know-about-roman-gladiators

(11) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ottoman_wars_in_Europe

A BBC series ‘Civilisation’, provides a history of art and society from the middle ages to the present day, over 13 episodes

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLXC6RzjHc2wugLza1kMWN_CRBuKRqQNTw

Books in this Series

Book 1 Egypt – Greece - Rome Empires come & Empires go 2 The Renaissance in Italy The Patron & The Artist 3 The Four Princes War, Terror & Religion 4 Northern Europe Revolution & Evolution 5 The American Dream Depression to Optimism

6 The Modern World The ‘…isms’ of Art

7 Past Voices Stories behind the Art All free e-book download

https://www.artystories.org

ARTY STORIES

The history of life and art across centuries,

of changing societies and changing cultures.

‘I think the concept for your work is both

creative and engaging’.

‘The links between art, history, society

are clear in the outline you provide and

the opportunities to stimulate young people’s

interest and imagination are evident’.

Sir Nicholas Serota,

Chairman, Arts Council, England

Society makes art

and art defines society’s culture

A Trojan archer, Temple of Aphaia, c. 490BC

Sackler Museum, Harvard, USA Vinzenz Brinkmann & Ulrike Kohn-Brinkmann