I

Magic London

All her life up to the time she was eleven years old, Betty had heard about, but never seen, her godmother. The reason for this, was that until a year ago, Betty’s home had been far away in the country, while Godmother Strangeways lived in London. Then, just when the child’s father and mother moved to town, Godmother decided to travel abroad. So it happened that Betty had been more than a year in London before she met the old lady who afterwards made such a difference in her life.

She never forgot the first day she met her.

“Your godmother has come back,” said her mother one morning at breakfast time, as with a curious smile she passed a letter to her husband.

“Has she? Oh, I do want to see her!” exclaimed Betty.

“Well, you will. She wants you to spend the day with her to-morrow.”

“Aren’t you and Dad coming too?”

“No, she wants you alone. She’s sending her car to fetch you to-morrow at eleven o’clock. Your father and I will go to see her another time.”

“I wish you were coming. I don’t know her, and I don’t want to be there all day alone with her,” grumbled Betty. “What will there be to do?”

“You’ll find she’ll provide plenty to do,” laughed her father. “Mind you don’t tell her though, how much you dislike London!” he added in his teasing voice.

“Why?” asked Betty.

“Because your godmother loves it. She’s a great authority on London. What she doesn’t know about it, isn’t worth knowing. It’s quite uncanny. I wish she’d write a book about it.”

“I can’t think how any one can love London,” Betty declared. “Such a horrid, big, ugly, dull place. I shall never, never like it!”

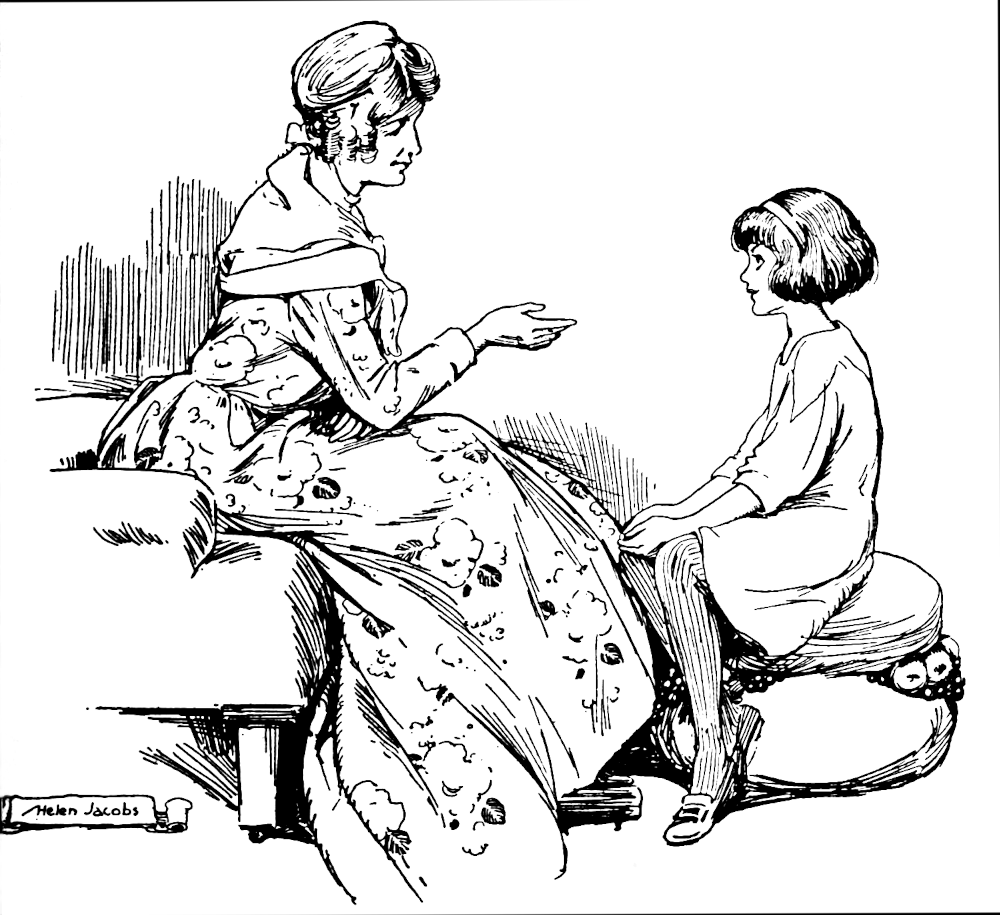

Godmother’s little car duly came round next morning, and after a drive, Betty found herself in a tiny room, in a tiny house, in a tiny street close to Westminster Abbey, seated opposite to a very handsome old lady.

“I’m sorry my godchild doesn’t like London,” this old lady remarked suddenly, in the midst of a conversation about something else.

Betty blushed and looked uncomfortable. She felt shy of her godmother who, as she had always heard, was very clever but “eccentric”—a word she thought meant different from other people.

“It’s all so confusing and noisy and there are such lots of ugly houses,” she began apologetically. “And I do miss the lovely country and our beautiful garden,” she added with tears in her voice.

“Of course you do,” said Godmother sympathetically. “But as it’s a pity to hate the place you have to live in, I’m going to make you think London the most fascinating town in the world.”

She spoke confidently, and just as confidently Betty said to herself, “You’ll never do that.”

“You think it’s ugly, don’t you?” Godmother inquired. “Well, so it is—in parts.”

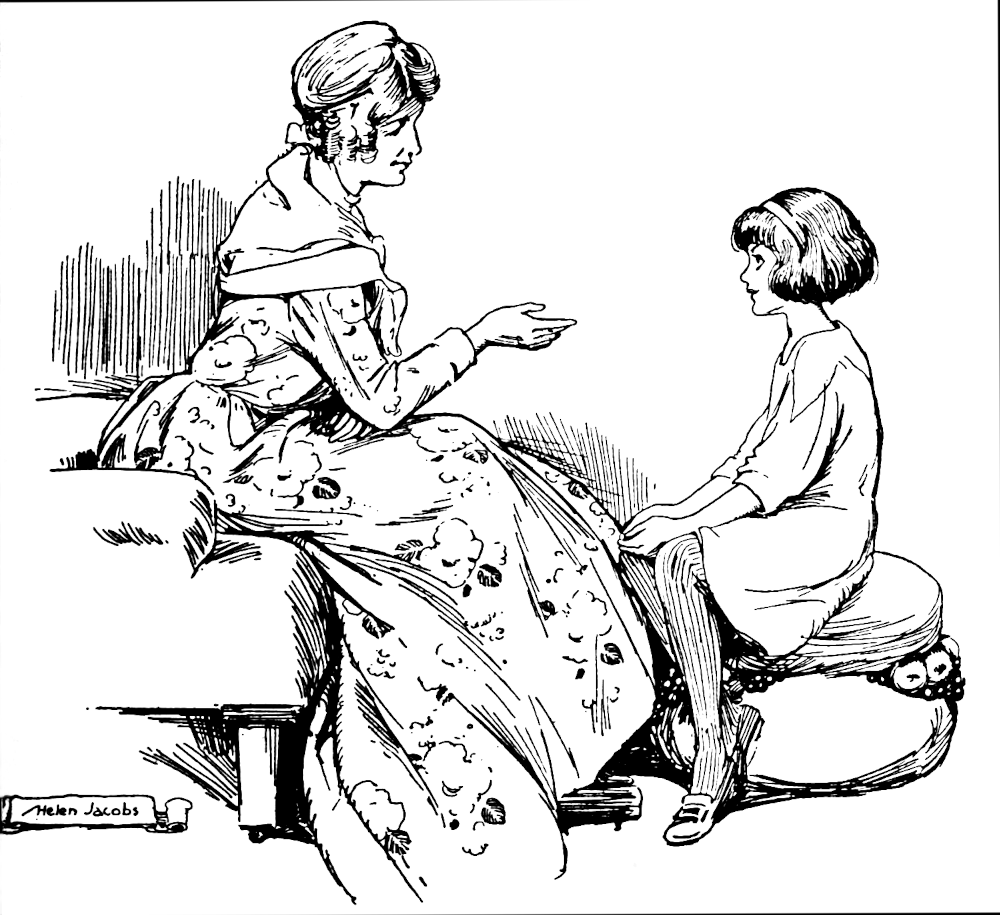

SHE WAS BEGINNING TO THINK SHE LIKED HER GODMOTHER

“Oh, it’s not all ugly,” Betty hastened to allow. “This little street is awfully pretty—and so quiet. It’s like a street in a country town. You can forget you’re in London. It’s a very old street, isn’t it?” She was forgetting her shyness and beginning to think she liked her godmother. She certainly liked the look of her. Godmother Strangeways was dressed in a way which Betty described to herself as “nicely old-fashioned.” She had snow-white curls fastened back behind her ears with tortoiseshell combs, and the ample-flowered silk dress she wore was, as her godchild decided, “just right” for the small white-panelled room with its old furniture and tall narrow cabinets filled with all sorts of curious things.

“Old?” repeated her godmother. “It’s about two hundred years old, and that, as London goes now, is rather ancient. But it’s new compared with the age of London itself. What is two hundred years compared with nearly two thousand?”

“Is London as old as that?”

“Where’s your history? Didn’t the Romans live here once upon a time?” asked Godmother Strangeways briskly.

“So they did,” murmured Betty.

“Well, some of them settled in this island soon after the birth of Christ, and that is nearly two thousand years ago.”

“But I didn’t know they lived in London?”

Godmother laughed. “They made London, child. The first London. And just in the place where it now stands, at the mouth of the Thames.”

“But was it called London then?”

“Something very like it. It’s earliest name was Llyn-din, and the Romans called it Londinium. You see how easy it is to get London out of that? They had another name for it as well—quite a different one.—They sometimes called it Augusta.”

Betty was silent for a minute, then after a quick glance at her godmother she said rather timidly, “Dad says what you know about London is quite uncanny. He says he wonders you don’t write a book about it. When you asked me to come to see you, he was very pleased because he said if any one could make me like London it was you. And of course as I have to live here I should like to like it!” She sighed rather hopelessly.

The old lady began to smile, and her smile was mysterious.

“Shall I tell you why I don’t write a book about London?” she said. “It’s because if I did, it would be considered uncanny, as Dad says.”

Betty began to look and feel excited.

“Oh, why? Do tell me why?”

“I’m not quite sure whether it would be of any use to tell you, but I shall know better in a few hours’ time, when I’ve seen a little more of you. I’m going to take you out for a drive now, before luncheon. The car is still at the door.”

Ten minutes later, Betty took her seat beside the old lady, and the car glided out of the quiet street into a busy thoroughfare. It was a lovely spring day, and she was glad to be out of doors in a part of London more or less new to her. She was also very curious about what Godmother had recently hinted, though she scarcely liked to question her on the subject.

They were passing Westminster Abbey now, and nodding toward it Godmother said:

“You don’t call that ugly?”

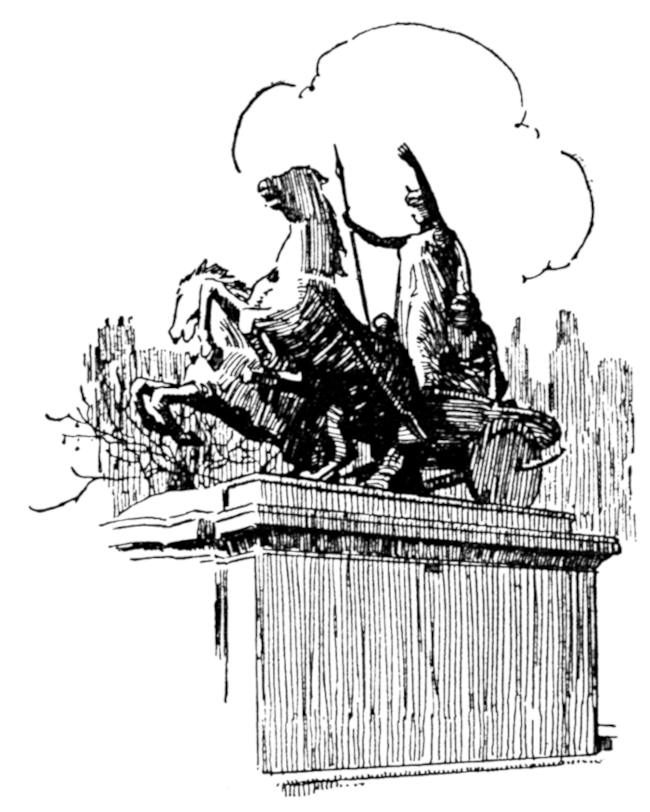

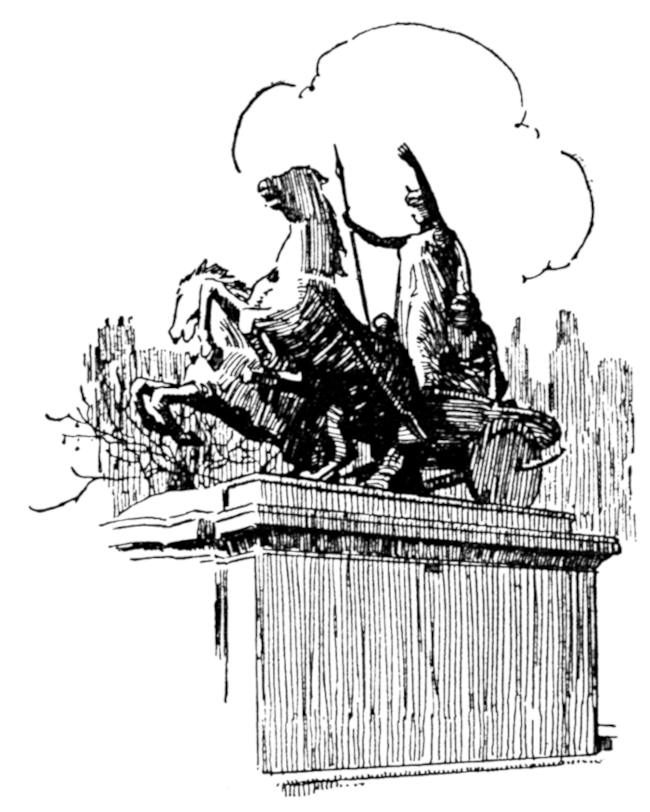

Before Betty could answer, they had reached the end of Westminster Bridge and turned on to the Embankment. Raised on the end parapet of the bridge, was a group of statues in which the chief figure was a woman in flowing robes furiously driving a strange-looking chariot.

“Do you know what that represents?” asked Godmother, when she saw Betty glance at the monument with interest. “It’s Queen Boadicea driving into battle. I only want you just to remember her name, because you may hear something about her later.”

Again Godmother’s voice was mysterious, and Betty glanced at her, with more curiosity than ever.

It was delightful to be driving by the side of the river with the spring sunlight sparkling on the water, but she wondered where they were going.

As though she guessed her thought, Godmother said presently, “We are going first to drive slowly over London Bridge.”

In a few minutes they were upon it, and the car was threading its way among the crowded traffic, between great vans and lorries and taxicabs and the carts and wagons of all sorts that rolled along with a ceaseless roar. Betty looked up and down the river lined with huge buildings, its surface covered with shipping of every kind, and it struck her that London was, after all, a wonderful city. At the other end of the bridge, Godmother gave Williams, the chauffeur, an order to return, and to stop as close as possible to The Monument, that enormously tall pedestal near the Bridge, which, as Betty’s father had told her, was put up in the reign of Charles II.

“Now I’m going to stay here comfortably in the car while you and Williams climb to the top of that column,” said Godmother, when the chauffeur had driven into a narrow side street. “Neither of you will mind the steps, but I certainly should.”

Betty was only too delighted at the prospect, and with Williams as escort, she mounted gaily higher and higher, till at last the final step was reached, and she stepped out on to the caged-in top of the pillar. What a marvellous view it was, of miles and miles of streets and houses and domes and spires, with the river running like a silver ribbon in the midst!

Williams also was impressed. “It’s a fine great city, miss!” he exclaimed.

“Well?” demanded Godmother, when presently they returned to the car. “What do you think of London in point of size?”

“It takes your breath away!” was Betty’s answer, as she settled herself comfortably for the homeward drive.

“It’s been lovely,” she declared, when they sat down to lunch in the quaint parlour below the sitting-room. “I do believe I’m going to like London after all, Godmother. It somehow seems quite different seeing it with you. I have such a funny feeling about it. Just as though it was a sort of magic place that might be awfully surprising.”

Godmother gave her a quick look, but said nothing except “I’m glad.”

After the meal, however, when they were once more in the white-panelled sitting-room which Betty already loved, she exclaimed all at once, “Now I’m going to tell you a secret.”

You may imagine how Betty pricked up her ears. But without giving her time to speak, the old lady went on, sinking her voice to a most thrilling whisper: “I have a magic way of seeing London. It’s a special gift, and I’m not going to tell you how I discovered that I possess it. Very, very few people have the gift, but from certain signs I think you possess it too. Would you like to try?”

Betty’s face was a study in perplexity.

“Yes—but how?” she stammered. “I don’t understand....”

Instead of explaining, Godmother Strangeways got up, and opened the door of a cabinet that stood between two narrow square-paned windows, took something from a shelf and, returning, dropped it into her godchild’s hand.

Betty gazed at the little object. “It’s a ring,” she began. “But a very old one, isn’t it? It’s so dark and stained.”

“It’s a very old one,” said Godmother. “It’s a ring once worn by a young Roman nobleman. Put it on to your third finger.”

Betty obeyed. “Now say these words after me.” She began to chant very slowly and distinctly certain words which, though she did not understand them, her godchild knew to be Latin.

Feeling as though she were in a dream, Betty began to repeat them after her, looking meanwhile at the clock on the mantelpiece which pointed to three o’clock.

Outside in the street, a boy was calling “Evening Paper! Evening paper!”

His voice was still ringing in her ears when the white-panelled room vanished, and she found herself standing in the sunshine on the bank of a river.…

ROMAN LONDON

For a moment she felt frightened and lost, till she saw that Godmother stood beside her. “Where are we? What is this place?” she stammered.

“London.”

Betty thought of the London through which she had driven this very day. She saw again the crowded streets, the streams of traffic, the long rows of shops, the huge buildings of all sorts; the churches, the banks, the railways. How could this be London?

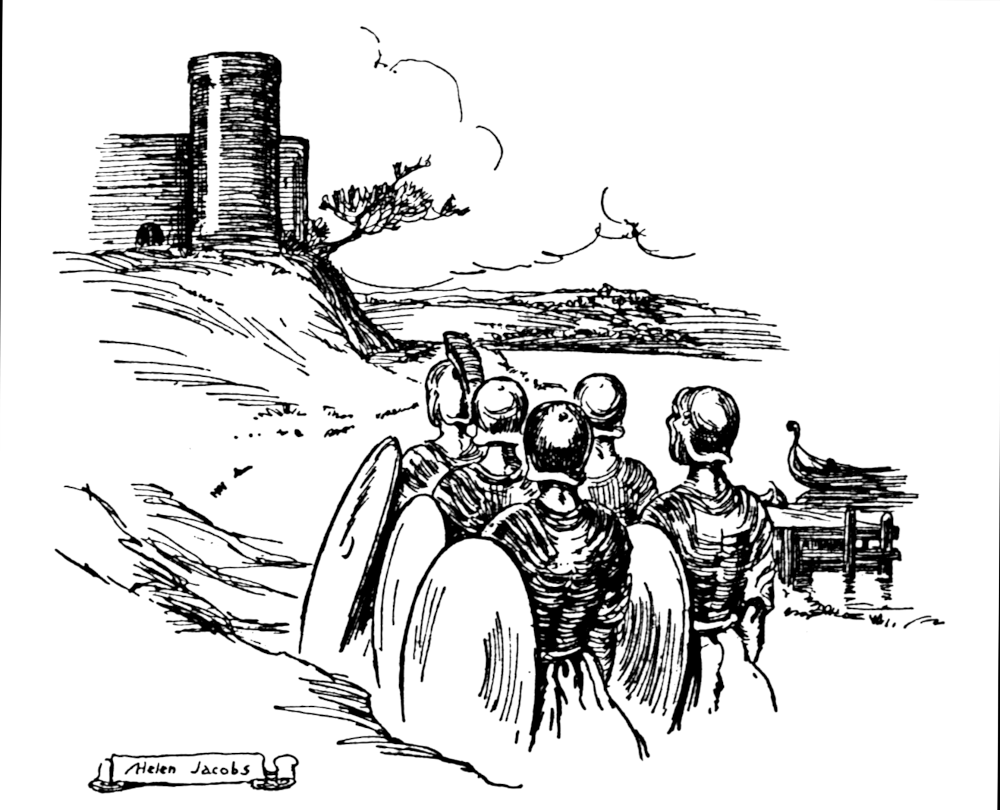

She looked down at the long grass on which she was standing,—grass that sloped to a clear river. On the opposite bank she saw something rather like a castle or fortress, a large brick building with zigzag battlements and turrets. This castle was reached by a bridge made of broad beams resting on piles of wood driven into the water, and beyond and on either side of the fort she saw, dotted here and there, strange-looking houses, with orchards and gardens and fields all about them.

“We drove over London Bridge this morning, didn’t we?” Godmother asked.

“Yes,” murmured Betty, bewildered.

“Well. There it is!” Godmother pointed to the bridge with its wooden planks and roughly-made railings of wood. “The London you know to-day began just about where we are standing now,” she went on, “and there”—again she pointed—“you see the first bridge that was ever built across the river.”

“Then we’re ever so far back in the Past?” asked Betty.

“We’ve gone back to a day four hundred years after the birth of Christ.”

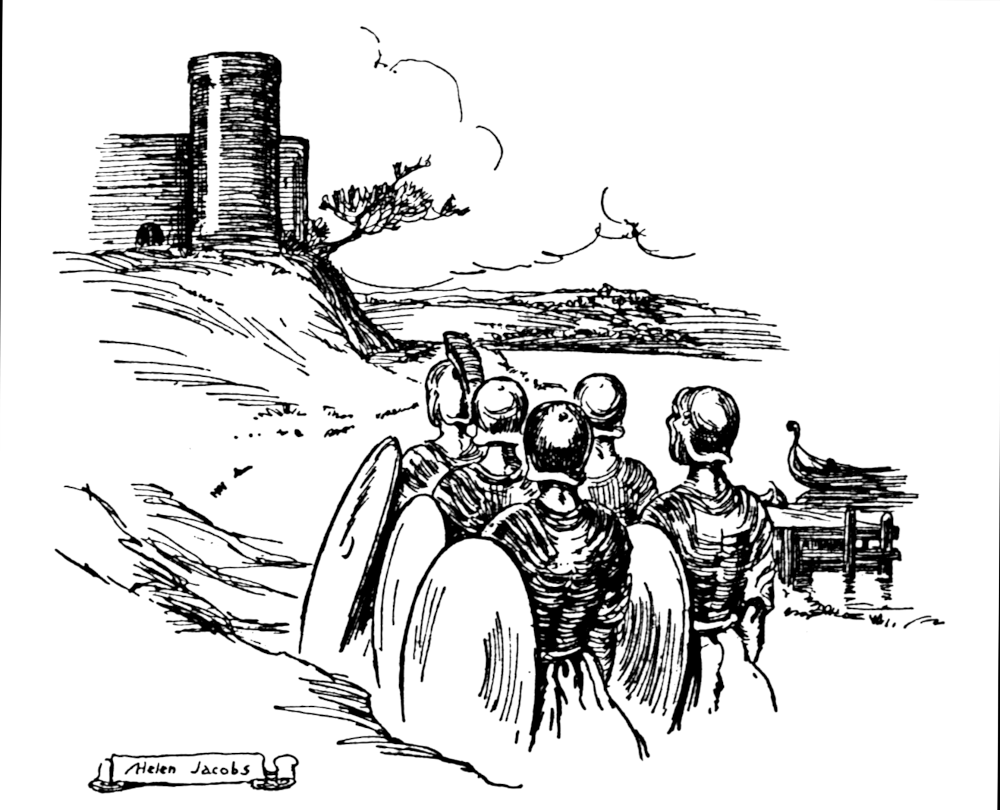

Before she had time to realize the strangeness of this, Betty’s attention was attracted by the most curious-looking boat she had ever seen, coming round a bend of the river. It had a high curved prow, and it was crowded with men wearing helmets that flashed in the sun, short tunics to their knees, and plates of brass covering their legs. Two rows of long oars stretched on either side of the boat, and as it drew nearer Betty saw that, though it had a sail, the helmeted soldiers were rowing it, and thus making it move very fast.

“Oh, look! look!” she almost shouted. “Who are these men?”

“Roman soldiers, of course,” said Godmother. “Remember the date. It is 400 years after Christ, and our country (called Britain then) has been conquered by, and belongs to, Rome. Many Romans have been settled here now for as long as three hundred years. That building,” she pointed to the Castle, “is the fortress where the Roman soldiers live. We shall see them disembark in a minute, and go into their barracks. This boat of theirs is called a galley, and it was in boats like it that the first Roman soldiers came sailing up this river Thames when they conquered the country.”

“Yes! yes! the boat is stopping! Now they’re going into the fortress!” exclaimed Betty excitedly, as with breathless interest she watched the soldiers being marched along the river bank by their officers.

“Can we go across the bridge?” she asked a moment later.

“Of course we can. No one sees us. No one hears us. We are invisible—for as long as we choose to be. Come, we’ll cross over to the fortress.”

Dancing with excitement, Betty followed her on to the bridge, over which, all the time she and Godmother had been standing on the bank, people had been crossing and recrossing. They were the strangest-looking folk imaginable, but so far she had been too confused and too interested in the soldiers to do more than glance at them.

“Let us stand here a moment, and watch,” Godmother suggested, drawing her back against the wooden parapet of the bridge.

“That’s a Roman nobleman,” she observed, as a fine-looking man passed, wearing a tunic, a white cloak wrapped round part of his body, the end flung over one shoulder, and sandals made of twisted leather. “That’s his villa over there.” She pointed to a house at some little distance set in the midst of blossoming fruit-trees.

“Here’s a British merchant coming!” she went on. “Look at his long furry trousers under the cloak, or toga as it is called, which he is wearing in imitation of the Romans. He has become so ‘Romanized’ that he copies the conquerors of his country in every possible way.”

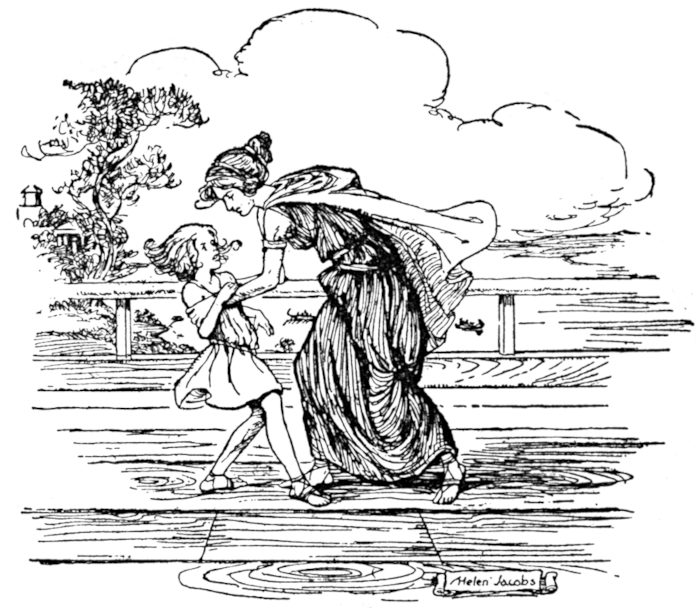

“But for all that, he doesn’t look a bit like a Roman!” declared Betty, as she stared at the man’s red hair, which hung to his shoulders. “Oh! do look at this dear little girl!” she exclaimed almost in the same breath.

A woman leading a pretty fair-haired child was moving towards them. The little girl, who was bare-footed, wore a straight gown made of woollen material, dyed blue. She had big blue eyes, and her tangled curly hair hung loose about her face. All at once, just as she passed them, a coin fell from her hand and, dropping through a chink between the planks of the bridge, fell into the water with a splash.

The woman, talking angrily in a language that sounded strange and barbarous, shook the child, who began to cry.

“Oh, poor little thing!” said Betty pitifully. “Her mother needn’t be so cross with her! They’re British people, I suppose?”

“Yes. That was the money to pay the toll at the end of the bridge,” explained Godmother, “and now it’s at the bottom of the river.”

But Betty soon forgot the little girl in her interest in watching the other people who passed and re-passed, and looking at the boats which floated up and down the stream laden with all sorts of merchandise.

THE SLAVE MARKET

“London, as you see, was an important port even in these far-off days, four hundred years after Christ,” Godmother remarked. “Tin and iron and lead and oysters are going away in some of those boats to other countries, and all sorts of things are coming in as exchange.... Now let us go on to the fortress and climb up to the battlements. Fortunately no one will interfere with us, and we shall get a good view of the country from the top.”

It was a very weird experience to pass unchallenged into the courtyard of the castle, filled with laughing, shouting and quarrelling soldiers. These men paid no attention to them, and Godmother led the way up a winding stone staircase to a pathway on the inner side of the battlements. From this height they had a wonderful view over the surrounding country, and as she gazed, Betty was lost in amazement.

The Monument, that great column to the top of which she had so recently climbed, was, she remembered, close to London Bridge. Therefore she must now be standing near the very same spot as that from which only this morning she had looked over London. It was an amazing thought.

She remembered the countless spires and domes and towers which rose far above their roofs, and the swarming traffic in all the streets.

Upon what a different scene she looked now! In place of the miles and miles of streets and houses, she saw along a narrow strip of the shore, right and left of the wooden bridge, a few steep lanes or alleys, lined with poor low dwellings. A few wharves and quays stretched along the bank of the river just below. There certainly a busy life went on, for men were loading and unloading boats. Behind the lanes leading down to the river, there was a belt of cultivated land, dotted over with gleaming one-storied dwellings which Godmother said were Roman villas, and beyond them, enclosing all the cultivated land, rose a strong wall with towers at intervals. But behind the wall came a long stretch of marshy ground, leading to the edge of a huge forest—a dark and gloomy and endless forest, clothing a line of hills, and stretching away, away, as far as eye could see.

Godmother was leaning on the parapet beside her.

“We are facing north now,” she said, and added suddenly, “You’ve been to Hampstead Heath, of course?”

Betty could not imagine what Hampstead Heath had to do with the scene upon which she was gazing, but she said, “Yes, we go nearly every Sunday.”

“Well, then, you have seen a tiny bit that is left of that great forest in front of you. There’s very little ‘forest’ about Hampstead Heath now, certainly, but such as it is, it is the descendant of that very one you see before you, which, a thousand years ago, stretched for hundreds of miles over this island.”

From the other side of the fortress, to which they presently moved, the view was equally strange, for here there was nothing to be seen but swampy land, just emerging from the water which everywhere surrounded it.

“We are looking south,” Godmother said, “and now that you see this great stretch of water right and left, you will understand why the first name of London was the lake fort.”

“Is that what Llyn-din means?” Betty asked.

“Yes. In the British language, Llyn-din means just that, and in the Roman language the word became Londinium—the Fortress on the Lake.”

“I do wish I could speak to some of the people,” said Betty, after a moment during which she watched the sunlight sparkling on the great expanse of water that ran under the oldest of all the London Bridges.

“Well, I can manage that for you. There’s no end to magic if you once learn how to work it,” Godmother added with her curious smile. “Let’s go down into the market-place.”

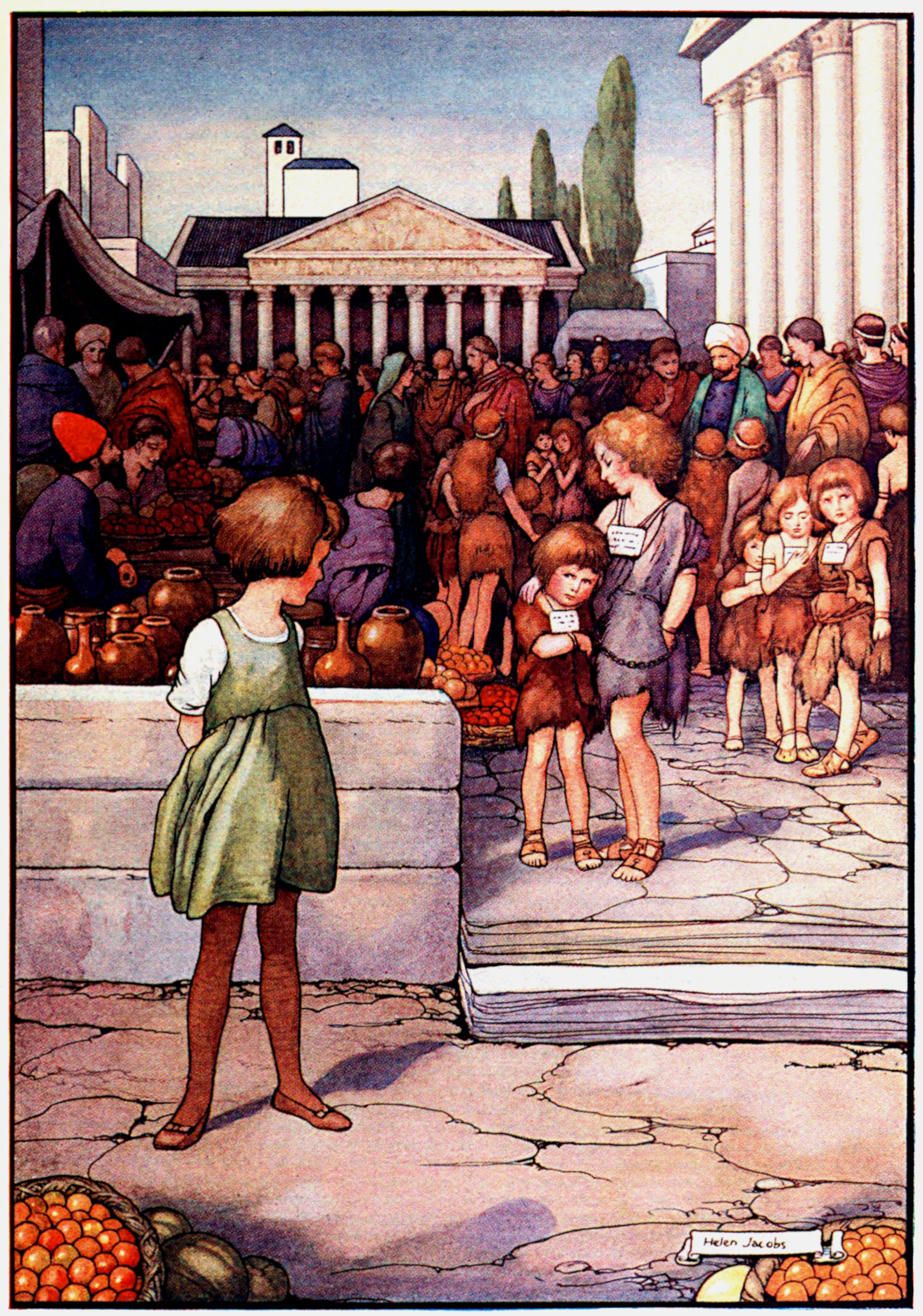

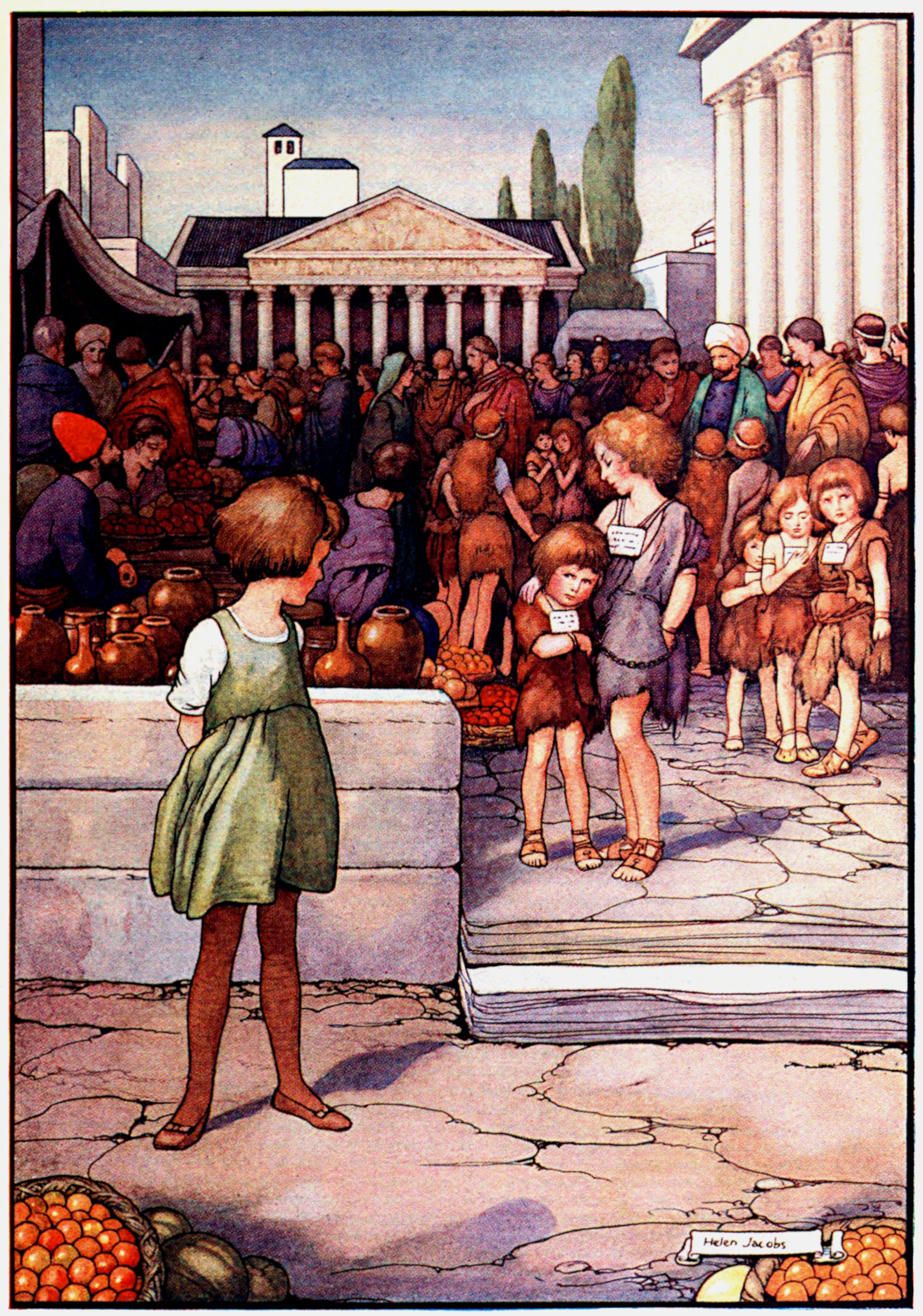

Between the houses that sloped down to the river just below, there was an open space, and from where she stood, Betty could see it was filled by a lively crowd of people, some evidently British, others Roman. They were buying and selling, and the noise and shouting of the crowd could be plainly heard.

“What’s that large building on the little hill just above the market-place?” Betty asked.

“That’s the Roman Hall of Justice, where people who have done wrong are tried, and sentenced to punishment,” replied the old lady as the child followed her to the top of the steps.

A few minutes later they stood in the market-place, where Betty could have lingered for hours watching the strange crowd. It was by no means entirely made up of Romans and British. Many dark-skinned, dark-eyed men from Eastern lands were there as well. “They are traders from lands even farther off than Rome,” Godmother explained. “For London, you know, has always been filled with foreign merchants. Some of these are buying British slaves to take back with them in their ships to their own countries. You see that little group of girls and boys over there, wrapped in rough skin coats? They come from a part of Britain beyond the forest, and they have been bought by that black-haired man with the turban and the gold earrings.”

Betty looked at the poor children pityingly as they stood huddled together, confused and frightened. It was dreadful to think of them being sold as though they were sheep or cows! But her attention was all at once distracted by a boy of about her own age, who, having passed quite close, all at once turned round and stopped. It was the first time that any one had seen her, for up to this moment both she and Godmother had been invisible. But it was evident that, to the boy at least, this was no longer the case. He smiled, and walking towards her, said, “You are a stranger? You would like to see my father’s house?”

He was a Roman boy, as Betty at once recognized, and strangely enough she did not feel it at all odd that she should understand his speech, though afterwards she knew it must be Latin. At the time, however, she wondered how he guessed that she was desperately anxious to go into one of the many Roman houses so beautifully set among orchards and gardens.

“Yes, if you please,” was all she could find to say.

“Come then,” said the boy, smiling again pleasantly, but paying no heed to Godmother.

Betty turned to her, puzzled and uncertain, but Godmother only laughed.

“Don’t trouble about finding me again. It will be all right. Go with him, and stay as long as you like. You’ll discover it’s not so long as you imagine.”

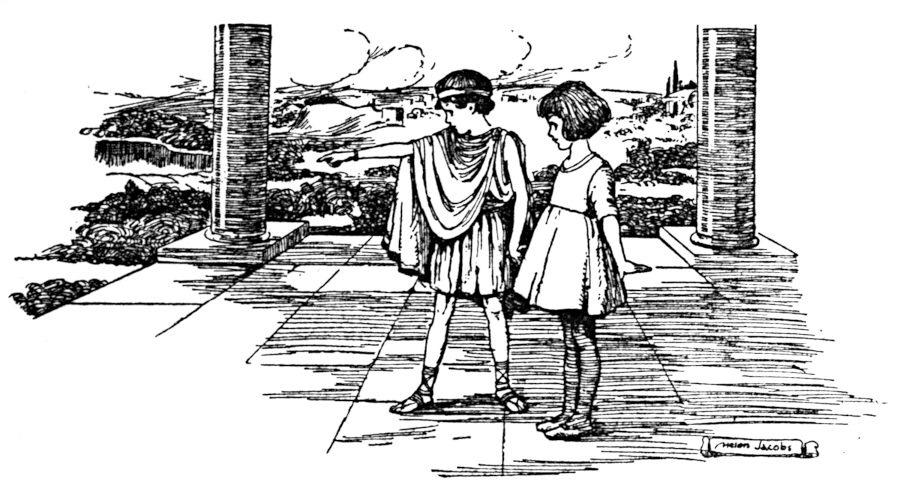

Thus encouraged, Betty very willingly followed her guide. He was a handsome boy, dressed very much as the Roman nobleman on the bridge had been clothed, except that the cloak he wore over his tunic had a broad purple band round its edge. That, as she afterwards learnt from Godmother, being the usual dress for Roman boys, for it was not till they were grown up, that they wore the tunic without this purple border.

“That is our villa,” he began presently when they came in sight of a long one-storied house surrounded by trees and shrubs. “My father has much land here, and many farms.”

“Will you tell me your name?” asked Betty shyly.

“My name is Lucius.... I will take you first straight through the house,” said the boy. By this time they had reached its entrance, and Betty caught a beautiful vision of rooms divided by pillars, each one opening into the next; of painted ceilings and walls, of coloured stone pavements, of couches with purple silk cushions upon them, and pedestals upon which statues stood. It was only a flashing glimpse she had of all this, and though she saw everything with the greatest distinctness, she was somehow conscious that none of it was actually real; that even Lucius was not really alive, even while she saw him as plainly as though he had been flesh and blood. Deep down in her mind, she knew that everything she saw and heard, was what had once existed but was over and done with long, long ago, and was only revived for a moment.

And yet everything looked so real. Just as this sad feeling came to her, she was walking over a pavement made of small coloured stones fitted together to make a pattern. This she knew was called mosaic work, and she noticed the design of it, which was that of a woman seated on the back of some animal in the centre of the pavement.

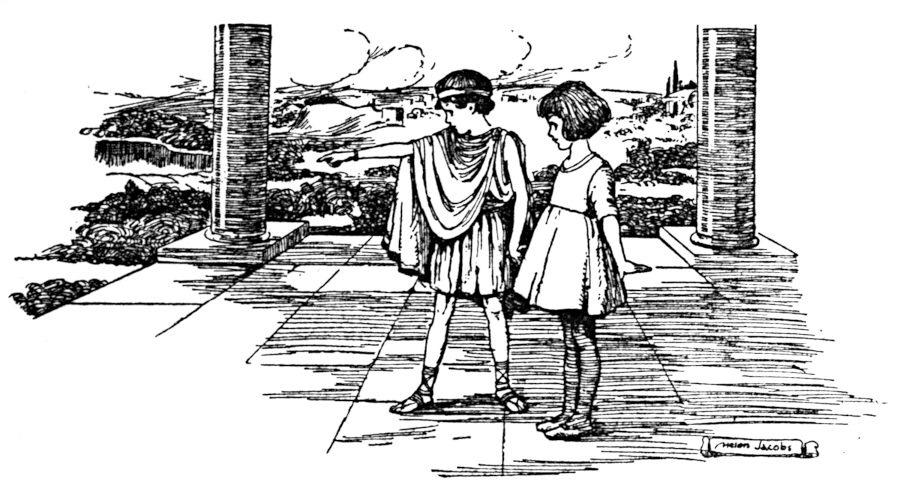

By the time she had walked through the villa and out of it upon a terrace overlooking the country, Betty had a confused idea of great luxury and beauty, displayed in a very different sort of house from any she had ever seen before.

“Ask me any questions you like,” said Lucius presently. But Betty scarcely knew where to begin.

“This country is called Britain, isn’t it?” she said at last, remembering her history. “And you Roman people conquered it?”

“We did,” answered the boy, smiling. “Long ago. Four hundred years ago.”

“And the British people are not angry about it anymore?”

“No. Why should they be? Everything is peaceful now.”

“But at first there was fighting, I suppose?”

“Long and bitter fighting,” said Lucius. “There is a story, which I believe is true, that when my ancestors first came to Britain, more than three hundred years ago, there was a British Queen who led men to battle against us. She actually took and burnt this town of Londinium—which was then, however, much smaller and less important than it is now.”

“Boadicea!” thought Betty, remembering in a flash the statue on Westminster Bridge.

But Lucius was again speaking. “My own family has been settled here nearly two hundred years. It was my great-grandfather who built this villa, and he was born in Londinium.”

“We call it London,” murmured Betty. But Lucius did not seem to hear her. “Then I suppose it was a good thing for the British to be conquered?” she inquired.

The boy laughed. “Without doubt. They were savages when we came, and we’ve taught them everything. From us they’ve learnt how to till the land,”—he nodded towards a field. “Those are British labourers working there now. They’ve learnt how to make roads after our famous Roman plan. You can see one of our roads from this corner of the terrace. And how to build houses and ships, and work in metal and do a thousand other things. Some of them have grown rich, and have been educated, so that they are as good scholars now as we are. Already Londinium is a famous port to which foreign merchants come bringing riches. My father says it will some day be a great city, equal to any city in the world.”

“It has become a great city!” exclaimed Betty to herself, remembering the London she knew. It was sad to think that if she had spoken aloud, the boy would not have understood her, and she hastened to ask another question.

“Are these British people Christians?”

“Oh yes!” said Lucius. “Ever since we became Christians ourselves, you know. Of course when my ancestors first came here, they themselves were pagans. They worshipped gods and goddesses like Apollo and Venus. But that’s a hundred years ago. Now Londinium is a Christian city, and we’re teaching the British to be Christians also. It’s rather difficult though, because a great many of them cling to their old gods. Still, most of them at least call themselves Christians.”

“Do you like living in this country—in Britain?” asked Betty after a moment.

“Oh yes. It’s my home. I was born here. But I should like to go to Rome—the city from which my great-grandfather came when he settled here, and built this villa. Perhaps I shall, some day,” he went on dreamily. “My father often says we may have to go back to our own land. There are troubles there. The barbarians are growing stronger and stronger, and some day Rome will need all the fighting men she can get to defend her.”

“But the British will have no one to defend them if you go,” objected Betty.

Lucius shrugged his shoulders. “No, poor things. Their state will be very desperate if enemies come to invade them when we are gone....”

Betty scarcely listened to the end of his sentence, for she had m