Introduction. Shinyalu

Shinyalu was not so different from any one of a thousand other villages in Western Kenya. It was a collection of small shops (mostly butchers with chopping blocks for counters and fly-covered meat hanging beside the blocks) and open-air stalls selling produce, used clothing, pots, tools, and hand-made goods out of handcarts or just from tarps spread on the ground. The village had a post office, general store, hardware shop, kinyosi*, and numerous cafes which served up generous portions of ugali*,beans, and sukuma wiki*. On market days Shinyalu would attract a thousand or more shoppers, coming to sell their livestock and/or to stock up on essentials.

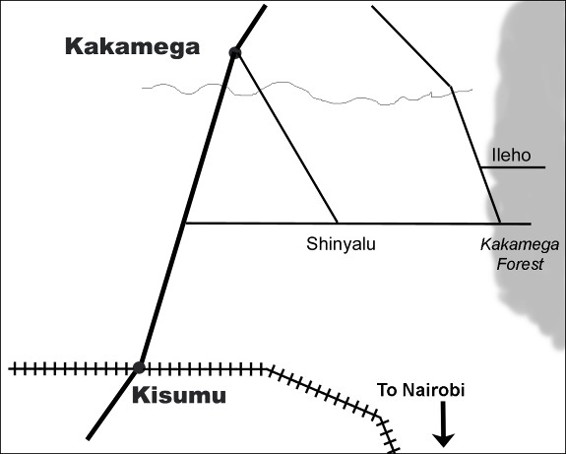

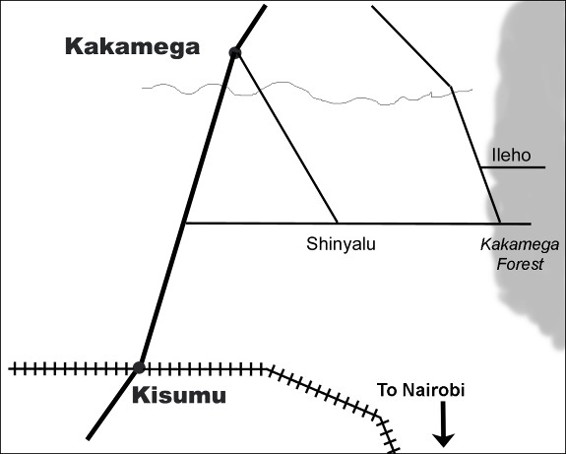

Shinyalu was situated at the T-junction of two dirt roads, one going south to the Kakamega Forest (and north to the paved road that leads west to Kisumu, on the shores of Lake Victoria); and the other going northeast to Kakamega, where locals could get most of their "luxury" items: furniture, windows, anything electrical, and exotic foods like pineapples, potatoes, or chocolate.

Smack in the middle of the T-junction there were always matatus* and at least half a dozen bodaboda* drivers parked, waiting for business. Vehicles actually negotiating the road would simply drive around them, being careful not to move too close to the edges, where the camber was so steep that they were constantly in danger of slipping into deep rainwater drains that extended down both sides of the road.

(*Swahili definitions appear in a list on here.)

Roads like these linked villages throughout the interior. In the dry season they were a series of rock-hard ruts and pot holes, that threatened the suspensions of anything that dared to travel on them. In the wet, they turned into slippery ooze that regularly sucked vehicles into the drains, where driver and passengers would be forced to wait for sufficient volunteers to drag them out, using strong ropes wrapped around the nearest tree.

A hundred metres east of the markets, on the road to Kakamega, lived Amy Walker. Amy was a thin, softly spoken, unmarried Australian Aborigine, in her late fifties. Amy had a twitch in her left eye, which had led to her being called Winky by those who knew her well. She had been raised by a European family in North Queensland, but fifteen years earlier she had become convinced that she should go and live with her "people". Amy believed that the Australian Aborigines had, centuries ago, migrated there from Kenya, and that the way to find her spiritual roots would be to return to Africa. Here in this remote corner of Kenya, she had learned to speak fluent Swahili, as well as Luhya, the more popular local dialect. Over the years, people in the village had ceased to think of her as an Australian, and had come to accept her as one of their own. One by one, she took in selected orphans, until she had nine additions to her household.

An independent Pentecostal church in Queensland had sponsored Amy at the start, but two years after she left Australia, she had a falling out with them over religious differences. Amy had been forced to find support from other sources ever since. Although she had been granted Kenyan citizenship, the local government offered her no help with finances. Nevertheless, circumstances and her own doggedness had led Amy to enough individual supporters over the years to provide her with a dilapidated van and a four-room brick building to house her and the children who lived with her.

The house had no running water or electricity, but it and the van were considered luxuries by her less fortunate neighbours. Locals often used those luxuries to argue that Amy owed it to them to take on more of the workload in caring for hundreds of orphans in the area.

"You can only scratch as far as your arm can reach," she would reply, quoting a local proverb. "If I try to do too much, we all lose."

Nevertheless, she was often pressed into assisting in other ways, as readers will soon see.

The most notable thing about Shinyalu, about Amy, and about all of the people living in Shinyalu, was just how typically unnotable they were. There are thousands of similar villages throughout the world, all populated by the poorer half of the planet's citizens. People in them live and die without anyone from the major metropolises ever knowing a thing about them. Entire villages could be wiped out, through disease, famine, civil war, natural disasters, or political genocide, and the rest of the globethose who think they know what is really happening in the world today might never even hear of it.

But this is the story of one singularly unnotable bodaboda driver, from that one unnotable village, who came to be part of events that shaped the world.