04

Turning Learning

into action®

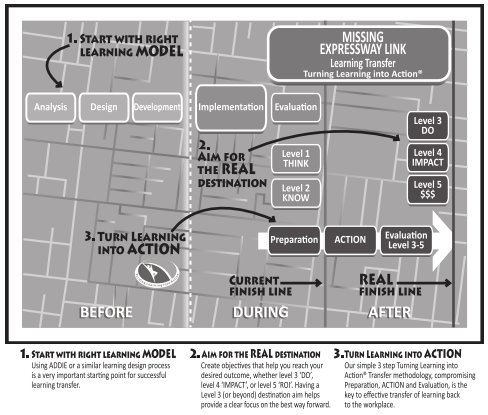

Transfer of learning is the missing link in effective learning and Turning Learning into Action® (TLA) is a proven learning transfer methodology that solves the problem. TLA is a series of specific, structured and accountable one-on-one conversations that occur at various intervals after the training event and it is the step change I referred to earlier.

I delivered the first TLA programme in a 12-person trial in April 2004. By May the results were confirmed and my client, a large premium automotive company, ordered the programme for 120 more people that year. I was onto something.

During 2005 we did an analysis of one group of 15 people who went through the TLA programme after some sales training against another group who did not. We analysed their average sales per month before the programme and analysed their average sales per month after the programme and compared the results to the norm within the business. The norm in this case was annual sales before May and average monthly sales after May. We made this split to take into account seasonal differences in automotive sales.

The average sales consultant had a 16.2 per cent uplift in their average sales per month between the five months prior to the training and the five months following the training and TLA. Everyone we analysed in the group had similar levels of experience and yet those who went through the TLA process had a sales uplift of 43.8 per cent over the same period.

These results confirmed that I really was onto something.

By 2007 my coaching team in Australia and I were delivering a year-long programme for another large automotive client for 400 mid-level managers across the organization for an 18-month period. There were four of us on the coaching team and as a business we were extremely busy.

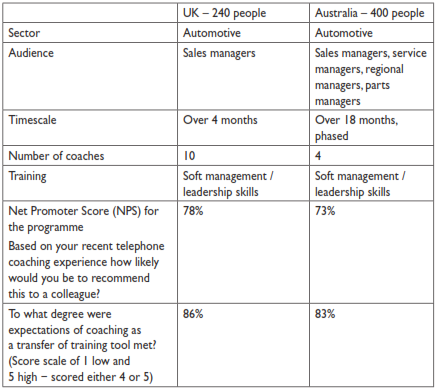

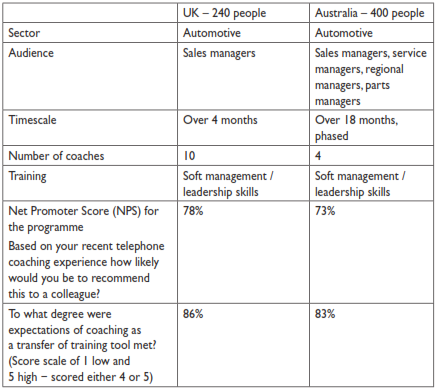

We were then asked to deliver TLA to 240 people in the UK. There were four large training events of about 60 people at a time held over the period of one month. The training was outstanding and our job was to ensure that all 240 people transferred the learning into their workplace. By the end of the year the results were in from the 400-person programme in Australia and the 240-person programme in the UK (see Table 4.1). TLA had been implemented in each case by two completely different teams trained in the same methodology and yet the results were almost identical.

TABLE 4.1 two programmes in large automotive companies in the Uk and Australia

Net Promoter Score (NPS), made popular by Frederick F Reichheld, is a really common and acceptable way to illustrate customer satisfaction. According to Reichheld companies whose customers award them an NPS of 75 per cent to 80 per cent plus have generated world-class loyalty. In other words, the customers of the businesses that are reporting an NPS in excess of 75 per cent are very happy customers – so happy that they will gladly recommend that business to other people. In the UK and Australian TLA programmes that we tested we achieved an NPS of 78 per cent and 73 per cent respectively.

Today TLA is being delivered in eight languages across the United States, Europe and Asia as well as Australia and New Zealand. It is solving the transfer of learning challenge for businesses across multiple sectors including banking and finance, technology, construction and manufacturing.

There can be little doubt that transfer of learning is the missing link in learning and TLA is a proven methodology for solving it. And the really good news is that there is no need to worry about learning countless different strategies, learn TLA, use it and training will genuinely be the lever for change that it always promised to be.

TlA as a lever for change

Businesses buy training because they want to see some sort of improvement in performance. The individuals on the training are there because they have some challenge, or need to improve a certain skill. As such they have a series of obstacles to surmount. Learning is the potential leverage point that will allow them to surmount those challenges and improve performance over the long term.

Imagine this process as a pole vault. At the start of the run-up the athlete’s pole is straight and taut. He then plants the pole into the ground; the pole bends and elevates the athlete upwards, over the bar. As the athlete clears the obstacle the pole straightens again and falls back to the ground. It has served its purpose and propelled the athlete over the bar and safely back down on the other side.

Pole vaulting was not originally a sport but a practical way to pass over natural obstacles in marshy places such as provinces of the Netherlands, along the North Sea and the Fens in parts of Britain. To cross these marshy areas without getting wet and without having to walk miles in roundabout journeys over bridges a stack of jumping poles were kept at every house and used for vaulting over the canals. Traditionally vaulting was about distance rather than height and they were used to short-cut travel time and allow people to get to where they were going faster.

TLA does the same thing by utilizing structure and flexibility. Each TLA conversation starts with a structure that acts like the pole vaulter’s pole and provides strength and purpose to the conversation. It allows the learner to use the power inherent in that structure to catapult themselves up and over their particular learning challenge.

As a facilitator of TLA I know the type of questions I will ask before I start the process (structure), but I never know what the answers will be (flexibility).

It is this flexibility that prompts additional questions and allows the individual to navigate the obstacle in the same way that the vaulter navigates the bar. It is the questions that really matter because they hold the context of the conversation, allowing for flexibility with the answers without being so flexible that the conversation is just a pleasant daydream.

The conversation is finalized with more structure as we then get the individual’s commitment about what they are actually going to do before the next conversation. The individual is accountable for this process and is choosing what to do next. As such he or she is taking responsibility and ownership of the change. This is when the pole vaulter’s pole straightens and falls to the ground while the vaulter lands safely on new ground. He or she has used the structure and flexibility to get to where they want to go faster.

Without this lever for change the behaviour change or application of learning sought by the training is rarely realized in the business.

As outlined earlier, the ADDIE model on which the vast majority of training is developed brilliantly facilitates the delivery of learning to the participant but misses the transfer of learning from the participant back into the workplace. Archimedes said, ‘Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the world.’ Turning Learning into Action® provides that lever to ADDIE’s fulcrum and together they can transform training effectiveness.

The power of reflection

Turning Learning into Action® is a practical methodology that puts reflection at the heart of the learning transfer process. The idea that reflection is central to learning is not new. It goes back to Greek philosophers such as Socrates and Plato. The Socratic Method is often referred to as a teaching method that focuses on asking rather than telling. Socrates challenged everyone around him, including Plato, to question their beliefs and reflect on learning to establish how it did or did not make sense to them as individuals. Sophocles also proposed that we learn by observing what we do time and time again.

More recently the English Enlightenment thinker, philosopher and physician John Locke believed that knowing was simply the product of reflection on experience and sensations.

As mentioned in Chapter 1, the importance of reflection in the adult learning process was also acknowledged by David A Kolb in his adult learning model (Figure 1.2, page 10).

The word ‘experience’ derives from the Latin word experientia, which means trial, proof or experimentation. In other words, the way someone gets experience and learns effectively is by using information or knowledge in the real world and using the results to fine tune future results. With enough trial and error anyone can learn anything and it is actually this trial and error process that is at the very heart of high performance.

The process of gathering experience therefore follows the Kolb adult learning model. First someone does something or engages in a particular activity or approach and the results of that action are noted. Sometimes the activity will be successful and sometimes it will not be successful but it is the experience and the outcome that drive learning. Ironically people learn the most when the outcome is not as the individual had anticipated. Under those conditions he or she is much more likely to engage in the crucial ingre-dient for learning and change – reflection. In life we rarely stop and reflect why we’ve been successful or why something worked out. Instead we just take the win and move on. When something doesn’t work, however, we are much more likely to stop and think about why that activity didn’t pan out as we had expected. It is because of that reflection that we are then able to fine tune our approach, see the failings and try again. This trial and error process develops expertise and it is only possible with reflection. Imagine how much progress we could make if we got into the habit of reflecting on our successes as well as our failures?

The problem with reflection is that it can look like we’re not doing anything – and that’s not ideal for employees. In modern business it is action that is king. Assessing the training needs of an organization can easily be classed as action, so everyone is happy with that activity. Designing, developing or sourcing training is also classed as action so everyone is happy with that.

The implementation stage is also action-focused so everyone is happy with that. Even the evaluation stage can be suitably complex and interesting so that people can assure themselves that they are doing something to solve the issue. In modern business it is doing that gets us promoted not necessarily thinking and reflecting. Management guru Henry Mintzberg wrote in the Harvard Business Review 20 years ago: ‘Study after study has shown that managers work at an unrelenting pace, that their activities are characterized by brevity, variety, and discontinuity and that they are strongly orientated to action and dislike reflective activities.’ This pace has only quickened – the drive for short-term results and maximizing shareholder value has ham-pered reflection and exacerbated the transfer of learning shortfall.

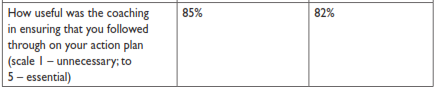

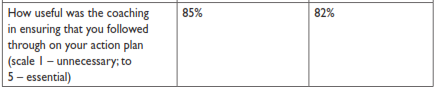

For reflection to really deliver the results that it is capable of delivering it must, however, be specific, structured and accountable (Figure 4.1). The word reflection has a very ethereal feel to it. It conjures up images of resting by a babbling brook, lying on the grass and gazing up at the clear blue sky.

That, however, is daydreaming and whilst pleasant it is a world away from the type of reflection that can transform learning and facilitate change.

Figure 4.1 the principles of effective reflection

Turning Learning into Action® facilitates specific, structured and accountable reflection through a series of one-on-one conversations after the training event. When people take a training programme they will have time during the training, if it has been well executed, to reflect on how the new information or skill may help them in their daily life. If the trainer has not run over time they will have completed some sort of action plan that is supposed to help participants follow through on the commitments they make as a result of the training. Typically, without structured follow-up, nothing actually happens with that plan and it ends up stuffed in the back of the training folder and dumped in the office on Monday morning never to be opened again.

If on the other hand there is specialized follow-up after the training event and participants are made aware of this from the start of the programme then the action plan becomes a living document. The follow-up conversation becomes specific and deals with the first issue on that plan, the structure of the conversation means that it is focused on moving the individual along and creating a framework where he or she must keep their agreements with themselves, or explain why they have not done so. When the individual has made commitments and reflects on how he or she is progressing, and is held accountable, then real change is not only possible but almost inevitable.

And that is the power of TLA.

TLA is not complicated. It is an enhanced coaching process that facilitates transfer of learning through a series of specific, structured and accountable one-on-one conversations that occur at various intervals after the training event.

When we consider that one of the most influential transfer of learning models (Broad and Newstrom) tells us that the critical time for transfer of learning is before the training then it is easy to see why learning transfer has so far been so ineffective. It certainly helps if the people on the training are enthusiastic and prepared but it is not indicative of success. In my view, what determines success or failure is whether or not there is a strategy for transfer of learning after the event.

We already know the statistics regarding failed training. We already know that we are wasting huge sums of money on training that never transfers back to the working environment. We know that people attend training and within weeks of the training event they are back at work doing exactly what they used to do prior to the training. It makes sense, therefore, to consider reallocating our training budget slightly to invest in training and learning transfer.

This shift will not alter the budget but it will radically alter results. One of the initial concerns I hear about TLA is the fear that one-on-one coaching will blow the training budget, but that’s not the case and I hope the results at the start of this chapter will provide reassurance that rolling out this methodology is extremely doable – even with large numbers of training participants. By combining training and TLA at the same time we may end up doing less training, but if we get the results we seek in the first place then we won’t need to keep buying training in the hope that the next programme will be different. TLA transforms training success and drives behaviour change into business. It is a cost-effective enhanced coaching methodology that when executed well will transform transfer of learning effectiveness.

Knowles and TlA

Knowles identified four principles for effective adult learning, which have become as good as law in the world of learning and development. As discussed in Chapter 2 the principles are:

● Adults need to be involved in the planning and evaluation of their instruction.

● Experience (including mistakes) provides the basis for learning activities.

● Adults are most interested in learning subjects that have immediate relevance to their job or personal life.

● Adult learning is problem-centred rather than content-oriented.

Like Kolb, Knowles too points to the importance of reflection – helping the individual to reflect on their own experiences and how they can make the learning relevant to them. In TLA, the TLA Plan puts the individual in charge of the learning transfer process and allows them to plan what they want to action following the training programme.

In the TLA conversations the specialist is always encouraging the individual to use their own experience, whether it is a success or a failure, to make the training relevant. Because they are in charge of the process and the learning they can choose what is the most immediately relevant to their job or personal life. It is their choice. And finally they are free and indeed encouraged to focus on how to rectify problems rather than get lost in the content.

It is important to realize that transfer of learning is not fully assisted or explained by the various learning theories but that effective transfer is also pulling the very best from change theory. Learning is just one part, once the learning is on board it is then important that we support individuals to change their behaviour over the long term. Learning has only really been effective when the person is using that learning on a regular basis and their behaviour has changed. Anything else is irrelevant.

At some point we have to accept that successful training and learning is actually less about the learning and more about change. The most effective change methodology is one-on-one personal coaching. When conducted over a period of time coaching allows the individual to identify what it is they want to change and then helps them to hold themselves accountable to follow through on what they want to do. Self-administered individual accountability is critical for change and I believe the very best way to achieve that is through enhanced coaching.

Coaching versus enhanced coaching

When I first explain TLA to people they often say something like, ‘Oh so it’s just one-on-one coaching then.’ Everyone in L&D knows about coaching; managers are commonly trained in coaching methodologies so they can coach their staff. I have met hundreds, possibly even thousands of managers who have been taught a basic coaching model or methodology for that exact purpose. But as we already know, learning something and effectively using it are two very different things.

One of the biggest challenges facing coaching in business today is the versa-tility of the process. While it can be used in many ways it is often a prover-bial ‘jack of all trades’ and master of none and is too broadly offered as a solution to all sorts of management problems. Ironically it is this broad application that is often touted as the reason that managers should learn it.

So the manager attends a half-day coaching course or a module that is part of a broader management skills programme. But back in the workplace, as soon as the individual being coached reacts or answers the manager’s questions in a way that is not familiar to the manager, perhaps in a way that was not adequately covered on their short training programme, they don’t know how to get the coaching session back on track. Coaching is a conversation and as such it is very easy to assume ‘everyone can do it’. Everyone can coach but it is not an automatic or easy skill to learn and it is certainly not something that can be perfected in a few hours.

Coaching, as most people recognize the term, is too fluid and flexible. As a result it works sometimes, for some people and not for others, and the people involved don’t really understand why. The basic coaching that is so often taught to managers therefore becomes too generic to be useful, especially for a time-poor manager. It is very difficult to work out the actual skills we need to be a good coach when those skills are applicable to so many different scenarios, and it is much easier to learn a skill when there are very definite parameters around what we are trying to achieve.

TLA is a very specific application of an enhanced coaching methodology that removes all the guesswork and creates a structure that identifies very definite parameters around effective learning transfer. The TLA specialist, by adding much needed structure, puts the individual in charge of their own transfer of learning and holds them accountable for the commitments they make at the end of the training event.

Enhanced coaching takes the flexibility of traditional coaching and adds structure to the coaching process to facilitate learning transfer effectively.

With enhanced coaching there is a fine balance between flexibility and structure. It is this balance that creates the results and removes the ambiguity from the coaching process, which allows us to deliver effective results consistently regardless of the training or the participant.

I remember watching Steve Jobs’s 2005 Stanford Commencement speech on YouTube. He was talking about connecting the dots of his life and how seemingly obscure and unconnected parts of his life came together in the creation of Apple. It is not often I feel justified in comparing myself to Steve Jobs but listening to his speech I looked back on my life and could see the same connection of dots and how seemingly diverse experiences and choices led me to the development of enhanced coaching and TLA.

In school in the UK I studied maths, art and English to A level. It was a combination that was frowned upon by many of my teachers because the subjects didn’t really belong together. At university I studied textile design, specializing in woven structure. What this course did for me was help me to appreciate fully the juxtaposition between structure and flexibility that is central to the success of enhanced coaching and, specifically, its application in training effectiveness through the TLA process. It was these two converg-ing ideologies working together that created beautiful designs. The textile design part tapped into my love of art and it was very creative. It was all about colour, dyes, fabrics and textures. It was fun, exciting and vibrant.

The woven structure part of the course tapped into my interest in maths, logic and process. It was all about numbers, patterns and systems. It was still fun for me but it wasn’t sexy or colourful. What I came to appreciate was that without the creativity and flexibility of the textile design the end result was dull and almost mechanical. And without the insights of woven structure the designs were weak and slap-dash. What created beauty was the precision and symmetry of woven structure coupled with the colourful and vibrant textile design. Each was diminished without the other and each was enhanced by the presence of the other.

It is this balance between structure and flexibility that is the crux of enhanced coaching in the context of learning transfer. Traditional coaching is often too flexible and creative. It can feel incredibly satisfying, nurturing and enjoyable to be listened to – personally I think coaching feels so good to so many people because the modern world is often frantic and we don’t sit down together and really discuss things and talk about issues in the way people did perhaps 50 years ago. Now we send a text message, eat dinner in front of a screen and communicate via technology rather than a good old-fashioned conversation. But whilst traditional coaching may feel good and people may feel nourished and energized, often just through being listened to, it doesn’t necessarily lead to behaviour change. It can lead to behaviour change when done properly but the vast majority of coaching is not done properly because it is not done with an action focus. It should be, and the model on which most coaching is built does include action, but the execution of that model rarely focuses on action.

Instead people get too carried away with the reflective part and don’t make it concrete. The coaching conversation becomes about the person’s ‘story’ and turns into a navel-gazing session, which may be enjoyable and even insightful for the person being coached but it is never made practical and therefore doesn’t necessarily lead to behaviour change. And, as we know, it is behaviour change that is currently missing and absolutely critical for successful learning transfer.

The difference between coaching and enhanced coaching – ie coaching that incorporates structure as well as flexibility – was driven home to me when I moved to Sydney. One of my first coaching clients had previously been paying $500 per hour with one of Sydney’s top coaches. At the end of each session she felt energized and excited. The conversation had been fun, interesting and inspiring. Only nothing changed. Nothing changed because coaching alone is often not specific, structured and accountable enough and so nothing takes place other than a great conversation. My new client recognized this and decided to hire me to make some changes – and she got significantly better results. Not necessarily because I was a better coach but because I balanced the need for flexibility with the need for structure. She got results and suggested very strongly that I needed to increase my fees, which at the time were under $100 per hour. Enhanced coaching guarantees results because it combines structure and flexibility for maximum impact and accountability.

Remember, in its simplest form coaching is about helping identify where an individual is trying to get to, looking at where they are now and bridging the gap between the two. Max Landsberg, author of The Tao of Coaching (1996), describes coaching as, ‘a powerful alliance designed to forward and enhance the life-long process of human learning, effectiveness and fulfilment’.

Coaching is not a passive process; it is not something that can be done to someone without his or her consent or involvement. Whereas teaching and training is focused on telling and sharing content, real coaching is a genuine collaboration, which creates ownership for change. And it is the quality of the questions that determine the quality of that collaboration and the effectiveness of coaching. By asking the right questions coaching helps the individual find their own answers and acknowledges the fact that in their life they are the expert. When a coach is helping an individual to make change in their life then the coach accepts that the individual is far better placed to decide how those changes should be made and what actually needs to happen and in what order. That individual has a huge amount of information available to them that the coach will never have and is therefore always the right person to decide what needs to happen.

It is this acknowledgement of expertise that makes coaching genuinely different from teaching or mentoring. In teaching it is the teacher or trainer who is considered the expert, and for transfer of knowledge that is as it should be. But as we have already established, learning new content does not automatically mean that an individual will use that content. Mentoring on the other hand is when an individual teams up with someone who has already successfully achieved what that person is seeking to achieve. And yet a good coach can coach on any subject regardless of personal experience.

The coach’s job is to follow a flexible and structured process that helps the individual to identify something they want to change, work out where they are in relation to that goal and how they can bridge that gap effectively.

Whilst mentoring can be extraordinarily beneficial it relies on a number of key variables. First, the individual being mentored must absolutely trust and respect the person who is mentoring them. If they don’t have total faith then the chances are they will only implement the pieces of advice that they secretly agree with anyway. Coaching avoids all those pitfalls because it doesn’t actually matter if the coach is proficient or has experience in a specific area or not. Also it is less important for the individual to trust or respect the coach as it is not the coach’s point of view that matters, it is the individual’s point of view that matters. If a coach follows the coaching process and encourages the individual to find their own solutions and, most importantly, holds them to account for those changes then change will happen. And that is what makes coaching so powerful.

What really separates enhanced coaching from standard coaching, especially in the context of learning transfer, is that it allows us to fully appreciate why traditional coaching results are so variable. If we think about having a conversation with someone to help them move from A to B we need to think about what is going to work and what is not going to work. So we all know that it doesn’t work to be told, we know that we need to encourage the individual to work it out for themselves. We all know that no one takes advice unless it is what they secretly thought anyway. We all know that we have to get the individual to be crystal clear about where they currently are and where they want to be so as to help them close the gap between the two. TLA is an enhanced coaching process that takes someone from where they are to where they want to be in the context of learning.

This book is about how to use enhanced coaching to facilitate transfer of learning using the TLA methodology so that we can get the results we want faster and with less hassle. TLA is the application of enhanced coaching in a very tight niche – helping people transfer learning from training back into the workplace.

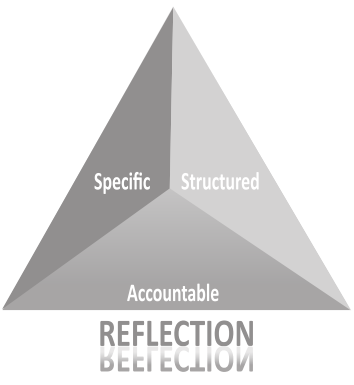

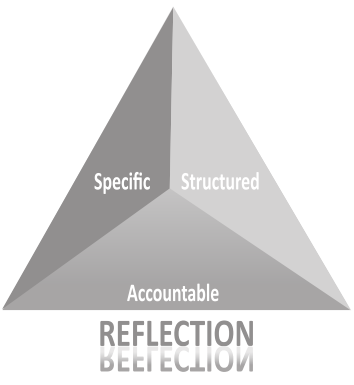

The learning transfer road map

The learning transfer road map (Figure 4.2) is a visual representation of how to combine the ADDIE process, evaluation and learning transfer.

It shows how each element fits into the learning process – before, during and after training – and how everyone must work together to focus on the real training finish line.

The learning transfer road map already includes ADDIE, which is the basis of instructional design, and most people are already using that process effectively.

Figure 4.2 the learning transfer road map

However, as I explained earlier, ADDIE alone will only take us to the current finish line. Typically the current finish line is the end of the training event and evaluation of people’s reaction to the programme, what they have learnt from the training or what they can demonstrate. So we are already getting to the current finish line really well but what we want to do is