Wh a t t o c h a nge? To what to change?

How to cause the change?

Don't people already have the capacity to answer all these questions? Does this mean that through TOCwe'll be able to generate an infinite amount of output?

You make it sound almost too easy. Is it?

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction to the Theory of Constraints __________1

Fundamental Analysis of the Theory of Constraints _2 About Chain Analogy______________________________ 4 About the Process of On Going Improvement _________ 7 About Thinking Processes (TP) _____________________ 10

The Fundamentals of the Thinking Processes________________ 11

Thinking Process Tools __________________________________ 12

Current Reality Tree (CRT)_____________________________ 12

Evaporating Cloud (EC) _______________________________ 13

Future Reality Tree (FRT)______________________________ 14

Negative Branch (NBR) _______________________________ 15

Prerequisite Tree (PRT) _______________________________ 16

Transition Tree (TrT)__________________________________ 18

Epilogue ________________________________________ 19

TOC Resources _______________________________21

Books, Writings by Goldratt ________________________ 21 TOC Books, Writings by Other Authors_______________ 28 Other ___________________________________________ 37 Published Articles in Magazines & Newspapers________ 38 Conferences and Symposiums______________________ 42 Videos __________________________________________ 43

TOC Case Studies _____________________________44

Brief Overview of Some Case Studies ________________ 44 Conceptual Analysis of Selected Case Studies ________ 46

Itemised Conclusions __________________________58

Introduction to the Theory of Constraints

The Theory of Constraints (TOC) is a portfolio of management philosophies, management disciplines, and industry-specific "best practices" developed and popularised over the past 20 years by physicist Dr. Eliyahu M. Goldratt and his associates. Most people are first exposed to the concepts through his book The Goal, (North River Press, 1984).

Dr. Goldratt has been described by Fortune Magazine as a guru to industry and by Business Week as a genius. His books The Goal, It's Not Luck, and Critical Chain, gripping fast paced business novels, are transforming management thinking throughout the world.

Goldratt's Theory of Constraints is being used by thousands of corporations, and is taught in over 200 colleges, universities and business schools. His books have sold over 3 million copies and have been translated into 23 languages.

The Theory of Constraints is an overall philosophy, usually applied to running and improving an organisation. TOC consists of Problem Solving and Management/Decision-Making Tools called the Thinking Processes (TP). TOC is applied to logically and systematically answer these three questions essential to any process of ongoing improvement: "What to change?" "To what to change?" "How to cause the change?"

More specific uses of the Thinking Processes can be used to significantly enhance vital management skills, such as: win-win conflict resolution effective communication team building skills delegation empowerment

Famous for spectacular results, the use of TOC has resulted in Proven Solutions created by applying the Thinking Processes (TP) in specific functional areas such as Sales, Marketing, Logistics, Finance, Accounting, Engineering and Project Management. Many of these solutions are discussed in detail in the books: The Goal, The Race, It's Not Luck and Critical Chain.

TOC recognises that the output of any system that consists of multiple steps where the output of one step depends on the output of one or more previous steps will be limited (or constrained) by the least productive steps. In other words, as paraphrased in The Goal, the strength of any chain is dependant upon its weakest link.

Where manufacturing is concerned, TOC postulates that the goal is to make (more) money. It describes three avenues to this goal:

Increase Throughput, Reduce Inventory, Reduce Operating Expense

As Dr. Goldratt notes, the opportunities to make more money through reductions in inventory and operating expense are limited by zero. The opportunities to make more money by increasing Throughput, on the other hand, are not limited.

More than that, though, TOC challenges us to define a goal and re-examine all of our actions and measurements based on how well or how poorly they serve it. This is done through a set of tools that help us identify and resolve bottlenecks.

Fundamental Analysis of the Theory of Constraints

The Theory of Constraints, as it is commonly called, recognises that organisations exist to achieve a goal. A factor that limits a company’s ability to achieve more of its goal is referred to as a "constraint." In The Goal, the demand for parts produced by a computer-controlled piece of equipment known as the NCX10 exceeded the machine’s capacity. Since the factory could only assemble and sell as many products as they had parts from the machine, the capacity of the factory to make money was tied directly to the output of the NCX10. The NCX10, therefore, was the constraint.

It is imperative for businesses to identify and manage constraints. "Because a constraint is a factor that limits the system from getting more of whatever it strives for, then a business manager who wants more profits must manage the constraints. There really is no choice in the matter. Either you manage constraints or they manage you." Noreen, Smith, and Mackey in The Theory of Constraints and its Implications for Management Accounting (North River Press, 1995).

The Theory of Constraints, then, is a management philosophy that focuses the organisations scarce resources on improving the performance of the true constraint, and therefore the bottom line of the organisation. Goldratt uses a Chain Analogy1 to help illustrate why this is the most effective way to get immediate results.

It may be relatively easy intellectually to recognise that an organisation must have a constraint, but it may be quite another thing to positively identify it. In situations when the constraint can be easily identified (which is usually because it is a physical constraint such as the machine known as the "NCX10" in the book The Goal), the five step Process Of On Going Improvement2 will provide the steps necessary to deal with the constraint. In situations when the constraint is not as easily sited (which is often because it has to do with the inter-relationships between the various "links" in the organisational "chain"), the Thinking Processes3 will provide the tools necessary to identify the core problem or core conflict and the tools needed to deal with it effectively.

About Chain Analogy

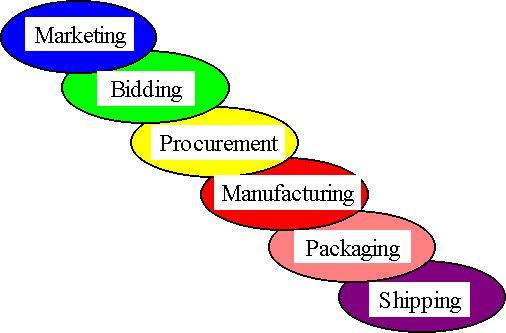

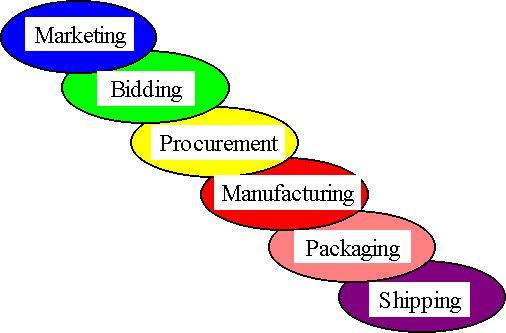

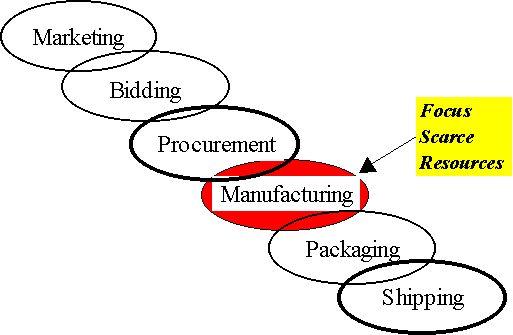

A manufacturing company can

be thought of as a chain of

dependent events that are linked

together like a chain. The

activities that go on in one "link"

are dependent upon the activities

that occur in the preceding "link."

The manufacturer in the example

above fabricates products to order. First they market their services. If the marketing is successful they will get some requests for proposals, and create

1More information in the section About Chain Analogy

2 More information in the section About Process Of On Going Improvement

3 More information in the section About Thinking Processes

some bids. If some bids are successful they will procure the necessary materials. Once the materials are on hand they will manufacture the product. Once manufacturing is complete packaging prepares the product to be sent to the customer. Finally, once packaged, the product can be shipped to the customer.

We notice that each step is dependent on the preceding step. That is, the product cannot be shipped until after it is packaged; the product can not be packaged until it is manufactured; the product cannot be manufactured until the necessary materials are procured; etc. It is this dependency that explains why the Theory of Constraints is so powerful when compared with "conventional wisdom."

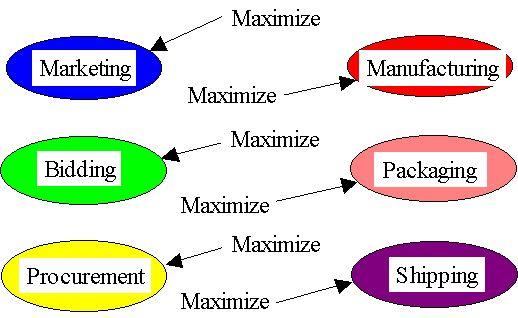

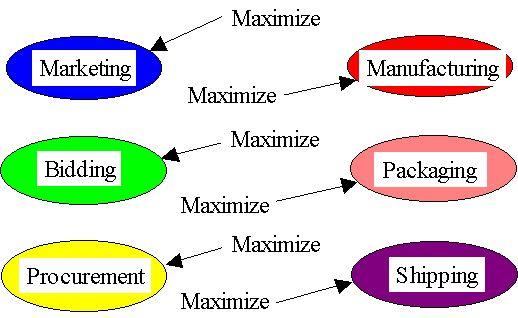

The chain pictured above is for a very simple company. Even so, it doesn’t really picture all the operations in the company. For example, billing and collection are not included. The typical company has a much more complex chain than is pictured here. To handle this complexity, management typically splits the chain up into links and endeavors to manage each link so as to "maximize" its performance. As a result, conventional wisdom is as follows:

• An improvement to any link in the chain is considered to be an improvement to the chain.

• System wide or "global" improvement is believed to be the sum of all the "local" improvement made within each link.

• This is analogous to saying the primary measurement of success in managing the chain is the weight of the chain, i.e. if one manager beefs up her/his link that makes the chain heavier and better.

As a result, all managers compete for scarce resources all the time. They all want to reach their goal of maximising the weight of their link, because they believe that is the way to maximise the effectiveness of the organisation.

By considering the following true story from a printing company, we’ll see another view. A team from a press operation in the middle of their system came to management with a proposal for continuous improvement. (We should think of them as being located in the manufacturing link above.) They had discovered an improvement that could be made to their press that would increase productivity 25%! It would cost the company only $20,000. Conventional analysis showed the payback period on this was relatively short. Would you authorise the investment?

Senior managers were about to sign the check when someone asked, "Where does the output of this press go? And, what is the status of work-in-process at that next operation?" It turned out that work was already queued up at the next operation. In other words, the company almost spent $20,000 so that the output of the press in question could wait 25% longer at the next operation! Had they made the expenditure they may have had a false sense of success when viewing the 25% increase in the "productivity" figures of the press, but the actual bottom line impact would have been a negative $20,000 because that money was spent without actually bringing any more money into the plant!

TOC Wisdom

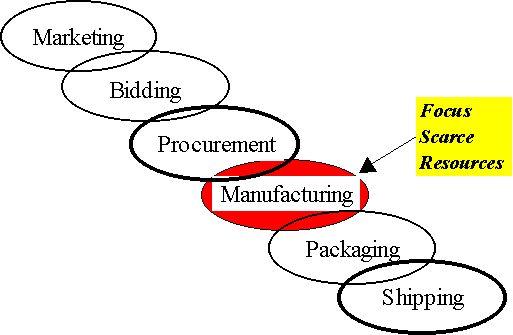

TOC says that management needs to find the weak link in the chain. In the example above it turned out that manufacturing was the weak link. That is to say that marketing was attracting sufficient requests for proposals, and bidding was winning a sufficient number of bids to keep the plant busy, and procurement was able to get the necessary parts on time, and packaging could handle everything that was manufactured, and shipping could keep up with packaging, BUT manufacturing could not keep up with the schedule.

In this case, what would be the bottom line impact of "beefing up" or improving the packaging link? Some cost savings may be produced, but the long term impact on the bottom line will probably not be great because it did not enable the company to fill any more orders than they are currently. (We remember that it is manufacturing that is limiting the rate at which orders are fulfilled.) The same holds true for shipping, procurement, marketing, and bidding. The one place where a significant impact can be made on the bottom line is at the constraint – in manufacturing in this example. The old saying applies: a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. As a result, TOC wisdom is as follows:

• Most improvements to most links do NOT improve the chain.

• System wide, or "global" improvement, then is NOT the sum of the local improvements.

• Thus a company should focus on "chain strength" (not link weight) by working to strengthen the weakest link – the constraint!

The result is that when using the Theory Of Constraints, managers do not fight over scarce resources. They all understand that once the constraint is known, the most bottom line impact can be gotten by channelling those resources to the constraint.

About the Process Of On Going Improvement

To manage constraints (rather than be managed by them), Goldratt proposes a five-step Process Of On Going Improvement. The steps in this process are:

1. Identify

2. Exploit

3. Subordinate

4. Elevate, and

5. Go back to Step 1 Identify

In order to manage a constraint, it is first necessary to identify it. In Eli Goldratt's book The Goal (North River Press, 1984), a machine known as the NCX10 was identified as the constraint. This knowledge helped the company determine where an increase in "productivity" would lead to increased profits. Concentrating on a non-constraint resource would not increase the throughput (the rate at which money comes into the system through sales) because there would not be an increase in the number of orders fulfilled. There might be local gains, such as a reduction or elimination of the queue of work-in-process waiting in front of the resource, but if that material ends up waiting longer somewhere else, there will be no global benefit. To increase throughput, flow through the constraint must be increased.

Exploit

Once the constraint is identified, the next step is to focus on how to get more production within the existing capacity limitations. Goldratt refers to this as exploiting the constraint. One example from The Goal was when the company and the labour union agreed to stagger lunches, breaks, and shift changes so the machine could be producing during times it previously sat idle. This added significantly to the output of the NCX10, and therefore to the output of the entire plant.

Subordinate

Exploiting the constraint does not insure that the materials needed next by the constraint will always show up on time. This is often because these materials are waiting in queue at a non-constraint resource that is running a job that the constraint doesn’t need yet. Subordination is necessary to prevent this from happening. This usually involves significant changes to current (and generally long established) ways of doing things at the non-constraint resources.

Elevate

After the constraint is identified, the available capacity is exploited, and the nonconstraint resources have been subordinated, the next step is to determine if the output of the constraint is enough to supply market demand. If so, there is no need at this time to "elevate" because this process is no longer the constraint of the system. In that case the market would be the constraint, and the TOC Thinking Process should be used to develop a marketing solution. However, we should be careful not to over activate the resource that was the constraint and produce unneeded inventory.

If, on the other hand, after fully Exploiting this process it still cannot produce enough product to meet market demand, it is necessary to find more capacity by "elevating" the constraint. In The Goal, schedulers were able to remove some of the load from the constraint by rerouting it across two other machines. They also outsourced some work and brought in an older machine that could process some of the parts made by the NCX10. These were all ways of adding capacity, or elevating the constraint. It is important to note that to "elevate" comes after "exploit" and "subordinate." Following this sequence ensures the greatest movement toward the goal of making more money-now and in the future.

Go back to step 1

Once the output of the constraint is no longer the factor that limits the rate of fulfilling orders, it is no longer the constraint. Step 5 is to go back to Step 1 and identify the new constraint – because there always is one. The five step process is then repeated.

It may appear that implementing TOC involves a never-ending series of trips through the five-step process – a kind of tool to assist in more perfectly balancing a production system.

This is not the case

. A fundamental principle of the Theory Of Constraints is that the combination of dependent events (such as the steps in a production system) and normal variation (which is always present) makes it literally impossible to ever fully balance a line. There will always be a constraint in the system. What creates chaos is allowing the constraint to move around – and a so-called "balanced" system will always experience a moving constraint due to normal variation. For that reason, companies that get the greatest financial benefit from TOC are those that make a strategic choice of where they want the constraint to be. They then manage their entire operation (product design, marketing, capital investment, hiring, etc.) accordingly. This allows the company to manage the constraint to their advantage rather than allowing the constraint to manage them.

About Thinking Processes (TP)

The Thinking Processes can be used when the constraint of the system is not obvious. This is generally the case when the constraint is not a physical resource, but instead is in the market or in the policies that exist regarding how we manage our organisation. (The Thinking Processes stand alone and as such can be used individually in appropriate circumstances.)

Goldratt believes that most organisations do not have a true physical constraint, or if they do, correct application of the 5 step Process Of On Going Improvement will usually break the constraint fairly quickly. Therefore, it is mastery of the Thinking Processes that is necessary for most organisations to break through their constraint.

To explore the Thinking Process further, we will have to examine the fundamentals.

The Fundamentals of the Thinking Processes

Simply stated, the Thinking Processes involve the rigorous application of effectcause-effect logic to answer the following three questions:

1. What to Change?

2. What to Change to?

3. How to Cause the Change?

The first question is the equivalent to the first step of the five step Process Of On Going Improvement: "Identify the Constraint?" Since these processes are generally used when the constraint is not a physical resource, there is usually no physical evidence (such as work-in-process inventory) to point you to the constraint. Instead you have to "map out" what is currently going on in your system. The logical mapping structure that is used at this point, is the "Current Reality Tree." This is not a simple task, but when it is completed successfully, we will know what to change.

That will bring us to the question, "What to change to?" While this question is intuitively obvious, there are two distinct steps to answering it.

1. Identify the breakthrough idea that will overcome the current constraint

2. Ensure that the "cure" that is derived will not be worse than the "disease."

The "Evaporating Cloud" is used to break through the core conflict that is currently constraining the organization. Then the "Future Reality Tree" is used to ensure that the undesirable effects we now are experiencing will, indeed, be changed to desirable effects by this breakthrough idea. The unintended negative consequences of the proposed solution are usually identified at this point using what are called Negative Branches. If these bad things that result from a good action can be prevented, then we can be sure the cure will not be worse than the disease. Now we know what to change to.

That brings us to question 3, "How to cause the change?" The simple answer is: get the people who are going to have to live with the change to create the action plan that is needed for implementation. The Thinking Process pro-actively involves those who are most effected by the change. These people are solicited for their vision of what obstacles might prevent the organisation from moving forward on this breakthrough solution. The workers are used to generate all the additional ideas that are necessary to implement the original injection. Once these are known, a plan is mapped out. The tools used when answering question 3: the "Prerequisite Tree," and the "Transition Tree."

Thinking Process Tools:

Current Reality Tree (CRT)

When using the Thinking Processes, the first of 3 questions we should ask is:

• "What to change?"

It is the equivalent of the first step of the five step Process Of On Going Improvement: "Identify the Constraint?" However, since the Thinking Processes are usually used when the constraint is not a physical resource, we can rarely use physical evidence like work in process (WIP) to identify the constraint.

Instead, we start with the evidence that is available: the negative effects that are apparent within the system. Examples of negative effects would be things such as

- frequently shipping orders late;

- excessive amounts of inventory;

- lead times that are increasing;

- poor human relations within the organisation.

Goldratt calls these "Undesirable Effects" or UDEs. The key is to realise that the UDEs are not the "real" problem -- they are only the visible effects of the real or "core" problem. The challenge is to map out the interrelated web of cause-andeffect that links the undesirable effects together. Once completed, one is generally able to identify the "core problem" near the bottom of the logical map.

This map is known as a "Current Reality Tree." Once properly constructed, we are in the position to know what to change.

Evaporating Cloud (EC)

When using the Thinking Processes, the second of 3 questions we should ask ourselves is:

• "What to change to?" The first step in determining the answer to this question is to understand why the core problem exists. (We should remember that the core problem was found at the

base of the logical structure -- known as the Current Reality Tree -- that was formed to find the constraint of the system.) It is assumed that managers are not stupid. If there was an easy solution to this core problem, it would have been solved long ago. No, there must be some conflict that underlies the core problem. Once this core conflict is identified, it is necessary to develop a breakthrough idea (referred to as an "injection") that will resolve the conflict. This is accomplished using a tool known as the "Evaporating Cloud."

The second step in determining "what to change to" is to test our breakthrough idea, our injection, to see if it will have the desired impact on your system. That is, would implementing the injection change the undesirable effects (UDEs) we are now experiencing into desirable effects (DEs)?

Future Reality Tree (FRT)

When using the Thinking Processes, the second of 3 questions we should ask is:

• "What to change to?" The first step in determining the answer to this question is to determine the conflict that underlies the core problem using the mapping tool called the Evaporating

Cloud. The main output of the Evaporating Cloud is a breakthrough idea, called an injection.

Once the injection is determined, we will have one necessary part of the solution. However, the injection is not sufficient to resolve the core problem. In fact, to be sure the proposed injection is indeed a "good" idea, it is important to check what the effect of implementing that idea would be.

Thus the second step in determining "what to change to" is to test your breakthrough injection, to see if it will have the desired impact on our system. That is, would implementing the injection change the undesirable effects (UDEs) we are now experiencing into desirable effects (DEs)? This is done by returning to the original map of undesirable effects (the Current Reality Tree) and inserting the injection at the appropriate place. Then, redraw the logical connections and see whether implementing this idea would, indeed, reverse the undesirable effects into desirable effects. If it works, we now know to what to change.

This mapping tool used in this step is the "Future Reality Tree" because it gives us a good picture of what the future can look like if we can figure out how to implement the injection. Notice that at this point, it is not necessary to know how we can implement our injection. In fact, sometimes it will appear that the injection is next to impossible to implement -- that it will happen only when "pigs can fly." Such injections are referred to as "Flying Pig Injections." If this is the case for us, we should not be in despair. There are effective techniques for grounding a flying pig.

Negative Branch (NBR)

After we have used the Current Reality Tree to map a clear picture of the core problem that is causing your current pain. After we have from the Evaporating Cloud, a breakthrough idea that can significantly improve our situation; we have from the Future Reality Tree, some assurance that this idea will indeed change the undesirable effects. We are currently experiencing into desirable effects in the future, we will need the input of the people who will be most affected by the proposed changes in order to ensure successful implementation.

The Thinking Processes are used in a very open and participatory fashion. We’ll work closely with the people who are going to be asked to change. Their involvement is absolutely vital to the long-term success of the implementation. As they view the proposed change that come with the "injection" and rosy "future reality" that accompanies it, they will tend to be resistant. We should always remember, that the core problem has probably existed for some time, and that there is a significant conflict underlying the current behaviour. Thus, the proposed injection will usually be counter to the culture of the organisation (or the subculture of a department or sub-group of the organisation).

People will usually look at the idea and say, "Yes, I see where your solution might work, but...." They complete the sentence with any number of unintended negative consequences that they fear will happen as a result of the change. For example:

• "If we make that much improvement in output, our department won't need as many people."

• "If we take the master schedule away from all the departments, we won't know what is coming down the pipe."

The Thinking Process intentionally seeks out these 'Yes, but there is a negative consequence' statements! They are important to preventing a failed implementation. The people who are involved in the affected process(es) will best know what these unintended negative consequences (Goldratt calls them "Negative Branches") will be.

So the Thinking process seeks proactively to identify them and then assists the person who brought the concern forward in figuring out how to prevent that negative consequence from actually occurring. Goldr