"you pommy bastard -you can't ride a horse can you?” After confirming his fears he cursed his luck and said that he was not going to drive all the way back into town and that he would teach me how to ride. I have always been grateful to that man for giving me a chance. I soon found out that the horses in that area of Queensland are only half broken and they seemed to sense that I didn't know what I was doing. I must have either got thrown or fell off a least fifteen times the first day but I kept getting back on I was determined to repay the managers faith in me. That night I crawled into my bed tired and bruised but pleased that I had stuck it out.

The next day I was introduced to the rest of the station hands. I was assigned to Bill one of the older hands, who was to show me the ropes. Bill was an excellent horseman being a horse breaker in his younger days. He taught me to have respect but not fear a horse. One of my team of six horses was a mare called "Crescent", she was a smaller horse than the rest, and that is probably one of the reasons I fell in love with her, it wasn't so far to fall to the ground.

When the drought got even worse we only kept one horse in work and hand fed them. Crescent and I became good friends. After breakfast we saddled our horses and rode out to inspect some fences, we repaired any small breaks and reported any that we couldn't repair. Because of the drought some of the water holes had nearly dried up and sheep had become bogged in the mud. Wherever possible we pulled them out and sent them on their way. Most of the water on the property was from bores -the water was pumped up from the depths of the earth. It came up boiling hot and then into bore drains which the sheep drank out of. So if we were thirsty and our water bags had run dry we would move the sheep droppings away with our hands and drink. I found out you will drink anything if you are thirsty

31

enough. After two weeks of coaching by Bill I was allowed to go out on my own, so I put my sandwiches in the saddle bag, saddled up Crescent, got my instructions on which paddock I was to ride and we were away. We were moving along the fence at a leisurely pace, the sun was nice and warm and sending both horse and rider half asleep, when Crescent did a huge sidestep. Within seconds I was wide awake, heart pounding hanging on for dear life. Then I saw him a huge goanna, which I thought was some sort of strange snake, scurrying away. I settled Crescent down, got off, talking to her all the time and rearranged the saddle, and decided it was time for a pot of tea. I found a small tree, the sheep who were under it were not very impressed but my "pommy" skin was more in need of shade than they were. I gathered up a few sticks and within a few minutes the billy was boiling and I was about to have my first solo lunch. What struck me at that moment was the absolute silence except for the buzzing of the flies who were trying to get my lunch before I did. The sun was just about to set when· I rode back in the evening and the homestead looked beautiful. I unsaddled Crescent and after feeding her gave her a thankyou slap and sent her on her way for a well earned rest in the horse paddock. Only then did I think about getting myself cleaned up and ready for supper. Bill had taught me well, he said always make sure your horse is OK first. The next morning it was my first turn to go and bring the horses up from the horse paddock to the yards ready for the days work. I got up before sun up and saddled up old King the night horse and set out to go and bring in the horses. Some of the horses had bells on so we could hear where they were. I thought I could hear them down to the left but old King knew they were over to the right.

Every time I pulled King over he went to go the other way.

Finally he gave a couple of bucks, threw me off and went and brought the horses up himself. The boys gave me heaps as they saw me walking back towards the kitchen with all the horses in the yard. When I told them that old King had

32

thrown me they laughed and said old King couldn't throw their Grandmother. I was very embarrassed to say the least.

Mrs Green the cook was very sympathetic and gave me an extra large breakfast to try and make me feel better.

On Sunday it was decided that we would go looking for a young wild pig to fatten up for Christmas. The wild pigs were getting into the bore drains and causing some damage, so the boss was all for the idea. We got out the old truck and drove down close to where we might find some. The Sow was not too happy about us stealing one of her family and gave chase

-we all broke even time racing back to the truck to safety.

When we got back to our quarters it was time to wash some clothes and relax for a couple of hours before getting ready for the next weeks work. It was while I was at Eulolo I met old Paddy the fencer. Paddy would work almost non stop for four or five weeks building fences then draw his cheque and head for McKinley -the nearest town. On arriving at the Pub Paddy would put his cheque on the bar telling the barman to send him back when it had run out. To my knowledge he never went any further afield than that. I learnt to drive while at Eulolo on the rough tracks around the station. It didn't matter if you left the road; the only time you had to be a bit careful was going through the gates. I remember one day I was having a driving lesson when the boss pulled the hand brake on and yelled for me to hit the brake. A big tiger snake was sunbaking on the track; we skidded on it and stopped just up the road. Mr Thomas jumped out of the truck and fortunately the snake slithered down a large hole. I sat motionless in the truck; there was no way I was going to move. To this day I don't know what he was going to do if the snake had not gone for its life but I would not have been surprised if he had started to wrestle with it. They breed them tough in the bush. One morning Mr Thomas noticed me walking with some difficulty. He asked me what was wrong; I told him that I was a bit saddle sore. To my dismay he grounded me. He told me that I would have to

33

work with him around the homestead for a few days. In those few days he taught me how to catch and butcher sheep for the cook. Fifteen or so wethers were kept in a small enclosure for this purpose. The first time I had to do it on my own I chased the wethers around without success.

They were too cunning they knew what my intentions were.

The only one I could catch was the family pet. The bosses young daughter came running down in a panic when she thought I was going to cut it's throat. The boss was training a young dog to work with sheep. He was a master at it and he would spend hours with the dog, patiently teaching it what it had to do. He told me that a good sheep dog was worth two or three men and didn't cost as much to keep.

One day I told the cook that my Mum could make a wonderful bread and butter pudding and that I really missed it. I really didn't think she was even listening to this young reminiscing pommy until a few days later she produced this beaut bread and butter pudding, I thought my Mum had migrated to Australia. Mrs Green was a lovely lady. I think she felt a little sorry for this sometimes lonely young bloke and wanted to make a bit of a fuss of me. Shearing time was exciting -we brought the sheep in stages starting from the furthest paddocks. I was amazed how many sheep we had there were thousands. Crescent developed a bad habit, if we were pushing the sheep along and some of them were a bit slow, she would get cranky and give them a nip on the rear that certainly made them move along. The shearers were interesting people; I took great delight in listening to some of the stories they had to tell. They lived a very hard life.

They worked hard, played hard and drank even harder.

Looking at some of the food their own cook dished up I was certainly glad that we had Mrs Green as our cook. A few of the sheep had some sort of cancer on their nose or ears so the shearers wouldn't touch them and they had to be put down. Mr Thomas taught me how to skin them and for that I got one shilling a head extra, which was pretty good money in my

34

opinion. After a few months I was starting to become a fairly useful horseman, being able to stay on even if the horse was a bit cranky and didn't want to work that day.

One day the boss got us all to go out and round up some brumby horses, we went deep into the scrub and camped out for a couple of days.

We had some very experienced horseman amongst us and Bill

said "Stay close to me Blue, this could be fairly dangerous."

Our horses were all wide eyed when we finally found a pack of wild horses and we all had to keep a firm hold. It was thrilling and exciting for this young eighteen year old

"Pommy". It was one occasion that "Crescent" forgot that we were mates. She was so excited she really put on a rodeo show. I felt the saddle starting to slip, she went for a fence and tried to put me over, but I hung on for dear life. Bill was so proud of me that day; he just patted me on the back and said

"That’s my boy, not bad for a new chum." When we got them all back to the station, the horse breakers began the slow task of breaking them in. It was fascinating to watch them work, they were so patient with the horses, and you could tell that they were in love with their job. John was the jackeroo at the station he -was a little older than me I think about twenty years old and we became good mates. He had a dog that went a bit stupid and starting killing lambs and the boss told him he had to get rid of it. It nearly broke his heart to have to ask one of the other men to put his dog down; he was a very sad boy for a few weeks after that. Mr Thomas told us that there was a horse race meeting coming up at a nearby town in a few weeks and he said "How would you like to ride in a race, Blue?" I was amazed he should ask me. He said I wouldn't have a chance, because he

was in the same race, but it would be good experience. We had a couple of ex bush race horses on the station, so when we were out of sight of the station we shortened the stirrups,

got high up on the neck of the horse and went for it. They thought they were in a race, it was very exciting as they galloped flat out across the paddock, miraculously avoiding 35

large cracks and holes in the ground. When I think back to what we did, it's a wonder we are still around to tell the story. The boss would have certainly had our hides if he had seen us. I can't remember too much about the race except I know I finished a distant last but it was good experience. This got me a little interested in horse racing. The Melbourne Cup was coming up and I picked out a horse called Delta. The main reason I picked it was because it was owned by a chap named Saunders. I had thirty shillings each way on it, and it won! I got back about nineteen pound, a fortune.

Meanwhile our little pig was little no more, every time we passed his pen we visualised him with an apple in his mouth, mutton does become a little monotonous after a while. Christmas finally came and the fatted pig was butchered and Mrs Green prepared a wonderful feast. We had a great time and stuffed ourselves silly, then retired to our quarters to sleep it off. The next morning there was a great rush to the toilets, it must have been too rich for us, so the pig had the last laugh. All the while I was working at Eulolo Eddie was working on another station some distance away and we didn't see each other for a few months. He came over to see me one weekend and said it was about time we moved on to something new, maybe go back to Sydney and see what was happening there. I wasn't too keen on the idea at first but then thought it would be nice to get back to the city life. So I gave notice, I got a very nice reference from Mr Thomas which I still keep proudly among my souvenirs. No sooner had I given notice, than the drought broke, the roads were impassable, so we had to wait for the weather to clear so we could get the mail truck back to Cloncurry. On arrival in Cloncurry we enquired what time the next train to Townsville would leave. The station master said they were going pretty well today only eight hours late. So we went to the pub to pass away a few hours. The train finally arrived and we climbed aboard, on what turned out to be a very slow but interesting trip. Sometimes the train would stop in the middle of nowhere, for

36

no apparent reason. I rather enjoyed this laid-back way of life,

where there was no hustle and bustle. It took about fifteen or sixteen hours to get to Townsville. We were hot, dusty and thirsty, so we booked into the nearest hotel so that we could refresh ourselves both internally and externally. The next day we caught a train to Brisbane and then to Grafton.

The McDonalds welcomed us back with open arms. I managed to get a part time job at the Great Northern Hotel in South Grafton, which more than paid for my board at the hotel. My job was to do the odd jobs around the place, like chopping the wood, killing and plucking chooks for the cook and looking after a small vegetable garden.

STEMMING THE RED MENACE.

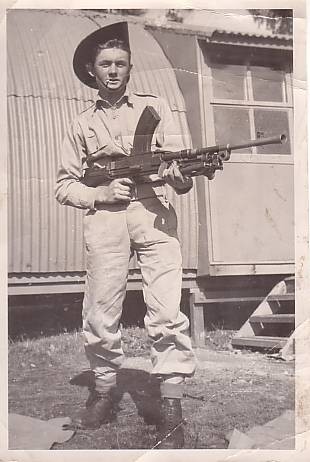

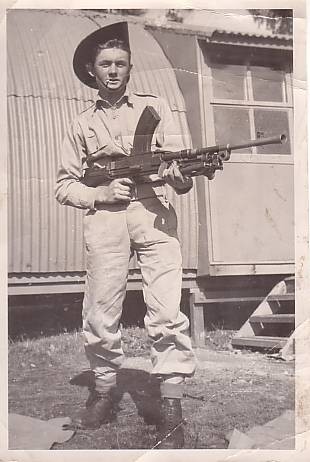

At the time there was a recession on and work was hard to find, so Eddie decided to join the Australian Navy and do his bit for Australia. The Korean war was under way and there were advertisements in the newspapers asking for volunteers to join a special "K" force in the army, you had to sign up for two years. I wrote to dad and got his permission to join and sent my application to Sydney. It only took two weeks for the army to send for me, they sent me a rail pass to get to Sydney, so I was on my way to stem the red menace. After joining my first posting was to Ingleburn for a couple of weeks, to learn how to march in step. Then it was off to Kapooka, near Wagga, for serious training. We had only been there about a week, hardly enough time to break in our army boots, when we were told we were going on an all day route march. The march took us out to a place called the Rock. The idea was that we were going to march to the Rock have a quick lunch and march back to camp. We were in such a bad

37

way when we arrived that they had to send for trucks to take us back, we were so unfit that we would never have made it.

That fitness level changed dramatically in the next few weeks, the NCOs’ made sure that we got all the fitness training we could handle. It took about three months for us to learn how to use a .

303 rifle and a Bren gun and how to lose our money at two up.

Two up started with a very large school on pay day and ended up with only two or three players (usually the ones running the school) the day before payday. I would say about fifty percent of the trainees at Kapooka were English and a great percentage of those would be people who had jumped ship. When you heard an English accent you would be fairly safe in asking what ship he had jumped. One such chap was Tommy or Geordie as we knew him.

We became good mates and stayed together through the whole two years we were in the army. We started to play war games where we would have mock patrols and run into ambushes, umpires would be observing to see who was killed or wounded.

Every war game that I was involved in I got told by the umpires that I had been killed. At first I thought it was great because I was able to have a rest while everyone else was running around. After a while I started to think "If this happens here what is going to happen when we go over to Korea?" A bit of a worry! So I started to get very careful and conscientious treating every bush or shrub as a potential enemy but to no avail. Around the next comer there would be an umpire to give me the dreaded news that I was a casualty. We finished our training at Kapooka and were taken back to Ingleburn prior to being sent over to Korea as reinforcements. When we got back to Ingleburn we had to parade individually before an investigation board, to make sure we were not running away from deserted wives or the taxation department.

Before going in I told Geordie I was going to confess about the jumping ship because I'd had this saluting everything that moved and whitewashing everything that didn't. When I told the members of the board they didn't appear that interested, I think they 38

realised if they sent back all the blokes that had jumped ship they wouldn't have many left so I didn't hear anymore about it. Another one of our guys had the brilliant idea on how to get out of the army -he was going to commit suicide. He got a length of rope tied one end around the beam in the hut and the other end around his neck. He then climbed on top of the wardrobe and made a lot of noise. The duty sergeant came to investigate the noise and pulled him down from the wardrobe. When they measured the rope they realised that he would have only bruised his feet if he had jumped -there was just too much rope. The private had made sure of that when he was setting it up. He should have been charged but the sergeant just told him not to pull a stupid trick like that again. On one of our final parades before going overseas the Sergeant gave us the good news that statistically only one in every three of us that went to Korea could hope to come back. Very comforting news. We lined up for our needles so that we wouldn't catch any nasties overseas. Then the sergeant marched us around the parade ground saluting every few yards to make sure the injections got into our system without losing the use of our arm. Then the day finally arrived, we were on our way to Sydney Airport to catch our plane to Japan. After a short stop at Darwin for refuelling we arrived at Manilla. On arriving at the hotel we would be staying at overnight, we were given five pound sterling spending money. The sergeant stationed there advised everybody to stay in the hotel; we would get better value for our money. Geordie and I decided to take his advice so after a shower and tea we went into the bar for a few beers. A few beers it was, we were broke by 9pm and preparing to hit the sack. The rest of the boys went out on the town, got back in the early hours of the morning, had a great time and had some money left. At least Geordie and I didn't have a hangover. Then it was on to Japan where we were transported to a holding camp at Hiro near Kure.

39

There was a curfew in Hiro; we had to be back in camp by 11pm. If the English Red Caps caught you after that time you were on a charge. The secret was to stay in the beer halls; the problem was to get back to camp without getting caught. One night a group of us were in a beer hall about midnight when someone noticed a huge fire some distance away. We went to the window and watched it, wondering what was burning. Later we went out the back door, walked to camp, keeping a sharp lookout for the red caps, climbed the fence to the safety of our camp. I went to my platoons’

tent and was greeted with the news that I was in big trouble, I had been reported missing with three others. Presumed burnt in the fire at the wet canteen (canteen that sold beer). I reported to the duty sergeant, telling him I must have fallen asleep and slept through the whole thing. He didn't believe me off course and put me on a charge of being absent without leave. The next day I was paraded before the commanding officer, he gave me a lecture, fined me five pound and confined me to barracks for seven days. For the next seven days I had to report to the duty sergeant every half hour in the evening to make sure I was indeed staying in camp. Depending who the sergeant was he would make me change from maybe battledress to working gear every half hour , or march around the parade ground where he could see me from the guard house. It was the middle of winter and it was snowing. One evening when I was on one of my marches around the parade ground, I reported to the guard house and the sergeant told me that I had a visitor.

Eddie's ship was in port in Kure for a couple off days and he had come to see me. We were both disappointed that I had got myself into strife and I couldn't get out to have a few drinks with him, but at least we were able to catch up on some news for half an hour. He told me that his ship was patrolling up and down the coast of Korea so he was on active service throwing a few shells at the "commos", softening them up for me, when I got over there to finish the war off.

40

Look out here I come!

41

We were told we were going to a battle training camp called Haramura about twenty five miles from Hiro, we marched up there in full gear with everything we owned on our backs. I was given the Bren gun and I soon found out how heavy they are, but from that time on my Bren gun and I was never far apart. We did a forced march up there keeping to the road all the way, except when a honey cart came along, and then we would make way for that. The Japanese don't waste anything and they used to load up a cart with containers which contained sewerage to be ladled onto the rice fields. These carts were normally pulled by the lady of the house with the man walking behind. Our forward scout would sight a honey cart coming down the road and would sing out "Honey cart starboard bow" we would all take a deep breath until we had passed it. When I found out what they did with their cargo I wouldn't eat rice for years. When we arrived at the battle school we were assigned to huts, there were no beds so we had to put our sleeping bags on the floor. We were told that we would not be able to get undressed at night. We would sleep fully clothed because we could, in fact would be called out at anytime of the night. It was in this camp I found out what the body can take. We were made to run up mountains in full gear and when we got to the top we were supposed to fire on an imaginary enemy. We had a corporal in charge of our section and he slept near the door. He took his boots off one night and placed them near his sleeping bag. One rotten bugger who didn't like him much had a leak in his boots instead of going out into the cold and making yellow snow.

We got a call to go out and fight the enemy (imaginary) and the corporal got a nasty surprise when he put his boots on in a hurry. After a month at the battle school we were extremely fit and ready to take on anyone. We almost ran the twenty five miles back to Hiro attacking hills in mock battle on the way, look out Korea here we come! We sat around Hiro camp for about two weeks doing almost nothing. We were even waited on at the dinner table by young Japanese ladies and that for

42

a private was almost unbelievable. Finally the call came for our section to go over to Korea as reinforcements. Geordie and I were assigned to the 2nd Battalion RAR to C

Company 3rd Platoon. I was the Bren gunner. When we joined our unit they were in reserve in area 3 behind the front line which was on the 38th Parallel. We went into training immediately, soon getting to know our new mates, my number two on the Bren was a young South Korean boy. Well I thought of him as young but he was almost the same age as me, about nineteen. The corporal in charge of our platoon was a chap by the name of Hutchins -I don't think I ever knew his first name. He was to make a career of the army and end up an officer. We were digging in a new line of defence in case we were ever pushed off the 38th parallel. The countryside we were in was very mountainous and barren and I couldn't help wondering why they were fighting over this particular place. We had to attend a lecture put on by the intelligence officer just to let us know what we were prepared to die for. The officer tried to explain the principals of communism to us and after about an hour of this Geordie and I looked at each other and whispered that we thought we might be on the wrong side.

This idea of sharing everything with your mates looked pretty good to us considering we didn't have much. While we were in reserve on this occasion we slept in two man tents placed in a row. Each one of us took turns of being on guard, the accepted way of doing this was to sit up in your sleeping bag with your rifle and when your hour was up wake the next person to you and so on until the last chap woke up the cooks. The system broke down one night and the cooks never got woken up. There was a hell of a blue and by investigation they eventually found someone to blame and the poor bloke ended up doing some time under detention. From then on each sentry had to do the right thing and march up and down for his full turn of duty, which I suppose we should have been doing all along. We got the call that we were to go up to the front line at night and take over from the British Battalion, the First Battalion The

43

Royal Fusiliers. We were loaded onto trucks and driven to close to the 38th Parallel. The trucks had their lights turned off; I don't know how the drivers got us there because it was pitch dark. We got off the trucks and marched the last few miles to our position on the front line. Prior to going up to the front line we had been told that we should not tell anyone who we were or when we were going up, all hush, hush. The Royal Fusiliers moved out and we moved in and stood by in the trenches, our pulses racing. We had just settled in when a voice addressed us over a public address system the Chinese had rigged up. "Welcome, 2nd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment", the female voice said. "We do not wish to fight you, why don't you go home to your wives and sweethearts"? We are only here to fight the American Imperialistic Pigs". So much for us not telling anyone who we were. I had my Bren gun with me in the fighting pit I was told to man and Choi Bong Choon my number two was with me staring out into the darkness, almost hoping that something would happen. Eventually dawn broke and we could see the valley we were overlooking, the enemy’s positions seemed so close. The position we had was called London Ridge, on the left of hill 355, considered to be one of the less dangerous parts to protect. During the next day we slept in our dugouts and tried to get used to this new way of life. Corporal Hutchins came back from a briefing to tell us that we were going out on patrol that night. Apparently the Chinese in front of our position were a bit cheeky and were coming right up to our perimeter so it was our job to push them back to their side of the valley. The first patrol was to be a learning process, not too ambitious, just to get a feel of what it was all about.

Just before dark we assembled in the closest trench to our perimeter and understandably we were all a little nervous, wondering what was ahead of us. Our forward scouts went out first very slowly, in reality we were very quiet but it seemed to us that we were crashing around like a lot of elephants. Suddenly a flare went up lighting up the area like

44

daylight, we all froze like we had been taught at training. We looked at each other and we looked like a lot of statues, as soon as the flare went out we hit the ground and waited. We waited for what seemed like an eternity until we got the order to withdraw. We withdrew and Hutchins asked for some cover. Within a few minutes we could hear the whistling of the shells as they went overhead.

It always amazed me how those New Zealand gunners could be so accurate. It was a comfort to know that it was the Kiwis that were supporting our part of the front line. We got back to our lines just before dawn and after passwords had been exchanged we were safely behind our own barbwire. We collapsed into our so called beds after devouring some American rations and slept like logs. We were awoken and told to get our weapons and ourselves ready for another patrol that night. It's amazing how you can improvise; our tin hats were very handy for washing in for instance and it's remarkable how much of the body you can wash with just enough water to fill a tin hat. They had a roster system in place where you could expect to be able to go back a few miles to a camp that was set up with showers and real beds. So about once every ten or twelve days you would be able to get all scrubbed up and have a decent feed

-it was heaven. After a few days we were getting used to the patrols and although we knew the enemy were there we didn't actually have any hand to hand combat. It was more a case of our forward scouts hearing them just ahead, withdrawing and bringing down the artillery. One evening we were on stand-by in our fighting pits, it was a pitch black night. Choi shook my arm and pointed to the trench.

We could hear someone creeping up the trench towards us.

I took Choi's .303 and cursed him for not having it cocked -

I slowly pulled the bolt back and waited with heart pounding. I saw a figure coming towards me out of the blackness and I yelled "Who's that?" Completely forgetting what the password for the day was. An alarmed voice answered, "It’s only me -Corporal Hutchins". The army nearly lost a promising young non commissioned

45

officer that night. On reflection I suppose he was checking up on us to see if we were awake or not. On another occasion we were not on patrol but were on stand-by. one of our lookouts thought they could see some movement, I was given the location and told to give it a couple of magazines with the Bren gun. It was usual to have a tracer bullet about every six or eight bullets in the magazine. Some joker had played a trick on me and filled a magazine with tracer bullets. When I opened fire it looked like Luna Park and we got a bit of a pasting by the North Korean artillery for our trouble, I always checked my magazines after that. After a few weeks in the front line our Battalion was pulled back into reserve, we were about five miles back and we occupied a line of smaller