COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY AND

COGNITIVE NEUROSCIENCE

by Wikibooks contributors

Developed on Wikibooks,

the open-content textbooks collection

© Copyright 2004–2006, Wikibooks contributors.

Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free

Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no

Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the

section entitled "GNU Free Documentation License".

Image licenses are listed in the section entitled "Image Credits."

Main authors: Aschoeke (C) Tbittlin (C) LanguageGame (C) Itiaden (C) Pbenner (C) · Mheimann (C)

Jkeyser (C) Ddeunert (C) Marplogm (C) · Pehrenbr (C) Ifranzme (C) FlyingGerman (C) Sspoede (C) ·

Asarwary (C) Lbartels (C) Smieskes (C) Apape (C) · Ekrueger (C)

The current version of this Wikibook may be found at:

http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Cognitive_Psychology_and_Cognitive_Neuroscience

Contents

CHAPTERS..............................................................................................................................4

01 Cognitive Psychology and the Brain................................................................................................ 4

02 Problem Solving from an Evolutionary Perspective........................................................................ 8

03 Evolutionary Perspective on Social Cognitions............................................................................. 25

04 Behavioral and Neuroscience Methods.......................................................................................... 33

05 Motivation and Emotion................................................................................................................. 47

06 Memory.......................................................................................................................................... 57

07 Memory and Language................................................................................................................... 66

08 Imagery........................................................................................................................................... 73

09 Comprehension............................................................................................................................... 81

10 Neuroscience of Comprehension.................................................................................................... 94

11 Situation Models and Inferencing................................................................................................ 109

12 Knowledge.................................................................................................................................... 125

13 Decision Making and Reasoning.................................................................................................. 146

14 Present and Future of Research.................................................................................................... 168

ABOUT THE BOOK............................................................................................................... 177

History & Document Notes............................................................................................................... 177

Authors & Image Credits.................................................................................................................. 178

GNU Free Documentation License................................................................................................... 179

Chapter 1

1 COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY AND THE BRAIN

live version • discussion • edit lesson • comment • report an error

Introduction

magine a young man, Knut, sitting at his desk, with his tired eyes staring at a monitor, surfing

Iaround, trying to find some worthy articles for his psychology homework. A cigarette rests between

the middle and index fingers of his left hand. Without looking, he stretches out his free hand and grabs

a cup of coffee located on the right of his keyboard. While sipping some of the cheap discounter blend,

he suddenly asks himself: "What is happening here?"

Around the beginning of the 20th century, psychologists would have said, "Take a look into

yourself, Knut, analyse what you're thinking and doing," as analytical introspection was the method of

that time.

A few years later, J.B. Watson published his book Psychology from the Standpoint of a

Behaviorist, from which began the era of behaviourism. Behaviourists claimed that it was impossible to

study the inner life of people scientifically. Their approach to psychology, which they assumed to be

more scientific, focussed only on the study and experimental analysis of behaviour. The right answer to

Knut's question would have been: "You are sitting in front of your computer, reading and drinking

coffee, because of your environment and how it influences you." Behaviorism was the primary means

for American psychology for about the next 50 years. One of the primary critiques and downfalls of

behaviorism was Noam Chomsky's 1959 critique of B.F. Skinner's "Verbal behaviour". Skinner, an

influential behaviourist, attempted to explain language on the basis of behaviour alone. Chomsky

showed that this was impossible, and by doing so, influenced enough psychologists to end the

dominance of behaviorism in American psychology.

As more researchers were once again concerned with processes inside the head, cognitive

psychology arose on the landscape of science. Their central claim was that cognition was information

processing of the brain. Cognitive psychology did not dispose the methods of behaviourism, but rather

widened their horizon by adding levels between input and output.

Modern technology and new methods enabled researchers to combine examinations of public

actions (latencies in reaction time, number of recalls) with physiological measurements (EEG and

event-related potentials, fMRI). Such methods, in addition to others, are used by cognitive science to

collect evidence for certain features of mental activity. From this, references and correlations between

action and cognition could be made.

These correlations were inspiration and thenceforwards the main challenge for cognitive

psychologists. To answer Knut's question the cognitive psychologist would probably first examining

Knut’s brain in that specific situation. So let's try this!

Knut has a problem, he really needs to do his homework. To solve this problem, he has to perform

loads of cognition. The light is gleaming into his eyes, transducing it from his retina into nerve signals

by sensory cells. The information is passed on through the optic nerve, crosses the brain at the lateral

geniculate nucleus to arrive at the central visual cortex. On its journey, the signals get computed over

complex nets of neurons; the contrast of the picture gets enhanced; irrelevant information gets filtered

4 | Cognitive Psychology and Neuroscience

Cognitive Psychology and the Brain

out; patterns are recognized; stains and lines on the screen become words; words get meaning, the

meaning is put into context, analyzed on its relevance for Knut's problem, maybe stored in some part of

memory. At the same time an appetite for coffee is creeping from Knut's hypothalamus, a region in the

brain responsible for controlling the needs of an organism. The appetite, encoded in patterns of neural

information, makes its way to the motor cortex where it is passed on to the muscles into Knut's arm.

A lot more could be said about this, and Knut's question remains unanswered, but this should be

enough to point out the complexity of cognition and the brain's importance. In this chapter, we are

going to dig deeper into the question of what cognitive psychology is and how it became this way, and

then draw connections to the brain and explain some of its most important parts.

Defining Cognitive Psychology

Cognitive Psychology is a psychological science which is interested in various mind and brain related subfields such as cognition, the mental processes that underlie behavior, reasoning and decision

making.

In the early stages of Cognitive Psychology, the high-tech measuring instruments used today were

unavailable. The idea of scientifically scrutinizing what was going on in a human mind was first

established during the late 19th century.

Psychology Laboratories were based on measuring observable features such as reaction time.

Nonetheless, there was a technique developed called analytic introspection. The latter is a method that

focusses on the subject’s inner processes. Here, the subject has to give precise reports about his or her

mental activity.

During the first half of the 20th century and naturally parallel to behaviorism, the behavioristic

approach became the main issue in psychology. The main emphasis was the examination of outer

expression of inner processes, rather than the mind itself.

Even though behaviorism had established itself as the mainstream, curiosity about the mind was

not diminished. In the 1950s, this inquisitiveness was released in a new science named Cognitive

Science. Cognitive Psychology became one of its subfields. The interdisciplinary approach of

Cognitive Science enabled the use of modern technology and new methods to combine examinations of

public actions (latencies in reaction time, number of recalls) with physiological measurements (EEG

and event-related potentials, fMRI).

Hereby, references and correlations between action and cognition could be made. Cognitive

Psychology is using these methods and additional ones such as Single and Double Dissociation and

brain lesioning to collect evidence for certain features of mental activity. Because of those correlations

that were found, the examination of the human brain and its functions has become one of the main

challenges to Cognitive Psychology.

Wikibooks | 5

Chapter 1

The role of the brain

Examination of brain damage has a long tradition.

The Ancient Romans observed that gladiators with head injuries often lost their mental skills, whereas injuries to

other parts of the body did not have such an effect. It

was inferred that there was a possible link between the

mind and brain. Today, the assumption that the mind is

somehow implemented in the brain is taken for granted,

and even the common-sense understanding presupposes

a relation between mental and neuronal processes.

Subsequently, research on the brain became more and

more important, and the psychological methods being

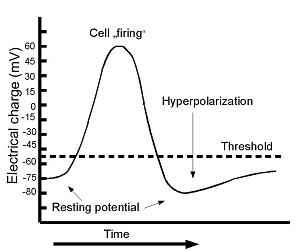

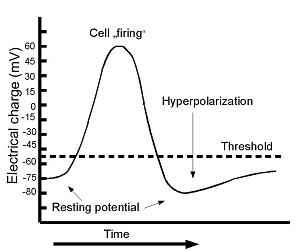

used shifted to systematic scientific examination of the Figure 1.1 - The resting potential is initially around -70

brain. The crucial question then became: How is this mV relative to the outside of the cell. Once the

relation realized, and what properties of the brain are threshold (-55 mV) is passed, the cell depolarizes and

capable of causing mental and cognitive events?

the polarity reverses up to +40 mV. Subsequently the

cell hyperpolarizes and the voltage becomes more

As it is not possible, in this introductory passage, to negative than the resting potential for a short period.

cover the entire configuration of the brain in an appropriate manner, we will just give a brief summary

of the concepts behind neural signal transduction, and smoothly switch over to the anatomy of the

brain. This in turn will then serve as background information in the attempt to link cognitive functions

to brain structure.

In principle, there are two classes of cells in the human brain: neurons and glia. Both are

approximately equal in distribution, though neurons seem to play the main role in information

processing. The actual signal transduction takes place in different ways. On the one hand, there is mean

electrical conduction, and on the other hand, there are complicated biochemical cascades which

transmit the data. Both variants can be subsumed to the concept of action potentials (Figure 1.1), which

generally carry out the signal transduction from one nerve cell to another.

For better conduction, the axons of the neurons are insulated by a so-called myelin sheath. The

myelin in the human brain is produced by a certain class of glial cell, the oligodendrocytes. This is

important because the decomposition of the myelin sheath is involved in diseases, such as as multiple

sklerosis.

Once the information perceived by the sensory organs is transformed into a sequence of action

potentials the data is, in a way, neutral, since it has no specific qualitive properties which indicate from

which sense the signal was original initiated. But how is the information encoded? In other words, how

can the variety of our conscious experience be caused by simple inhibition and excitation of nerve cells

embedded in an admittedly complex system? Because of the lack of better metaphors, the answer is

often given by comparing the brain to a modern digital computer. Parsing the world into objects,

making inferences, having associative memory and the like can be analyzed by developing

computational models. The underlying paradigm is that the information is represented by the rate of

action potential spikes. How this is exactly realized is the aim of research of biophysics, a subdiscipline

of neurobiology.

In cognitive psychology, however, the methods used differ. This is because the main interest is not devoted to the organization of single neuron circuits, but rather to the larger, functional units in the

6 | Cognitive Psychology and Neuroscience

Cognitive Psychology and the Brain

network.

References

• M. S. Gazzaniga, R. B. Ivry, and G. R. Mangun, Cognitive Neuroscience, Norton &

Company, 1998, ISBN 0393972194

• E. Br. Goldstein, Cognitive Psychology, Wadsworth, 2004, ISBN 0534577261

• M. W Eysenck, M. T. Keane, Cognitive Psychology, Psychology Press, 2005, ISBN

1841693596

• M. T. Banich, The Neural Bases of Mental Function, Houghton Mifflin, 1997, ISBN 0-395-

66699-6

• E. R. Kandel, J. H. Schwartz, T. M. Jessell, Principles of neural science, 2000, ISBN 0-07-

112000-9

Links

• PDF file of the "ethics code" of the American Psychological Association

• Cognitive Psychology miniscript by Fabian M. Suchanek

• Famous papers in the history of cognition

live version • discussion • edit lesson • comment • report an error

Wikibooks | 7

Chapter 2

2 PROBLEM SOLVING FROM AN EVOLUTIONARY

PERSPECTIVE

live version • discussion • edit lesson • comment • report an error

Introduction

estalt psychologists approach towards problem solving was a perceptual one. That is, for them,

Gthe questions about problem solving were:

• how is a problem represented in a persons mind, and

• how does solving this problem involve a reorganisation or restructuring of this

representation?

Restructuring is basically the process of arriving at a new understanding of a problem situation -

changing from one representation of a problem to a (very) different one. The following story illustrates

this:

Two boys of different age are playing badminton. The older one is a more skilled player, and

therefore it is predictable for the outcome of usual matches who will be the winner. After some time

and several defeats the younger boy finally loses interest in playing, and the older boy faces a problem.

The usual suggestions, according to M. Wertheimer (1945/82), at this point of the story range from

'offering candy' and 'playing another game' to ' not playing to full ability' and 'shaming the younger boy

into playing'. And this is what the older boy comes up with:

He proposes that they should try to keep the bird in play as long as possible - and thus changing

from a game of competition to one of cooperation. They'd start with easy shots and make them harder

as their success increases, counting the number of consecutive hits. The proposal is happily accepted

and the game is on again.

Insight

There are two very different ways of approaching a goal-oriented situation. In one an organism

readily reproduces the response to the given problem from past experience. This is called reproductive

thinking.

The second way requires something new and different to achieve the goal, prior learning is of little

help here. Such productive thinking is (sometimes) argued to involve insight. Gestalt psychologists

even state that insight problems are a separate category of problems in their own right.

Tasks that might involve insight usually have certain features - they require something new and

nonobvious to be done and in most cases they are difficult enough to prevent that the initial solution

attempt is successful.