whom they slew and hanged on a tree… (Acts 10:39)

Concerning Attis‘s death, Doane remarks:

Attys, who was cal ed the ―Only Begotten Son‖ and ―Saviour,‖ was worshipped by the

Phrygians…. He was represented by them as a man tied to a tree, at the foot of which was a

lamb, and, without doubt, also as a man nailed to the tree, or stake, for we find Lactantius making

this Apol o of Miletus…say that:

―He was a mortal according to the flesh; wise in miraculous works; but, being arrested by

an armed force by command of the Chaldean judges, he suffered a death made bitter

with nails and stakes.‖130

126 Price, R., 87.

127 Tacey, 110.

128 Acharya, SOG, 281.

129 Higgins, I, 499.

130 Doane, 190-191.

In his book Divine Institutes (4.11), Christian writer Lactantius (c. 240-c. 320) relates that, according to his

oracle, the sun god Apollo of Miletus was ―mortal in the flesh, wise in miraculous deeds, but he was made

prisoner by the Chaldean lawgivers and nailed to stakes, and came to a painful death.‖131 If the oracle

really had recounted a genuinely ancient account of Apollo‘s passion, then we have a pre-Christian

mythical precedent for that of Jesus. Moreover, the identification of Attis with Apollo is apt, since both

were taken in antiquity to be sun gods and discussed together, such as by Macrobius and the Emperor

Julian ―the Apostate‖ (331/332-363 AD/CE), the latter of whom said that both Apollo and Attis were ―closely

linked with Helios,‖132 the older Greek sun god.

Death of Attis

(Archaeological Museum of Ostia, Rome)

Tomb/Three Days/Resurrected: We have already seen Dr. Fear‘s commentary that Attis was dead for

three days and was resurrected, worth reiterating here:

The youthful Attis after his murder was miraculously brought to life again three days after his

demise. The celebration of this cycle of death and renewal was one of the major festivals of the

metroac cult. Attis therefore represented a promise of reborn life and as such it is not surprising

that we find representations of the so-called mourning Attis as a common tomb motif in the

ancient world.133

The death and resurrection in three days, the ―Passion of Attis,‖ is also related by Professor Merlin Stone:

Roman reports of the rituals of Cybele record that the son...was first tied to a tree and then

buried. Three days later a light was said to appear in the burial tomb, whereupon Attis rose from

the dead, bringing salvation with him in his rebirth.134

There is a debate as to when the various elements were added to the Attis myth and ritual. In this regard,

Murdock writes in ―The Real ZEITGEIST Chal enge‖:

Contrary to the current fad of dismissing all correspondences between Christianity and Paganism,

the fact that Attis was at some point a ―dying and rising god‖ is concluded by Dr. Tryggve

Mettinger, a professor of Old Testament Studies at the University of Lund and author of The

Riddle of the Resurrection, who relates: ―Since the time of Damascius (6th cent. AD/CE), Attis

seems to have been believed to die and return.‖ (Mettinger, 159) By that point, we possess clear

discussion in writing of Attis having been resurrected, but when exactly were these rites first

celebrated and where? Attis worship is centuries older than Jesus worship and was popular in

some parts of the Roman Empire before and well into the ―Christian era.‖

131 Lactantius, 245.

132 Athanassiadi, 204.

133 Lane, 39.

134 Stone, 146.

In addition, it is useful here to reiterate that simply because something occurred after the year 1

AD/CE—which was not the dating system used at that time—does not mean that it was influenced

by Christianity, as it may have happened where Christianity had never been heard of. In actuality,

not much about Christianity emerges until the second century, and there remain to this day

places where Christianity is unknown; hence, these locations can still be considered pre-

Christian.

It is probable that the Attis rites were celebrated long before Christianity was recognized to any

meaningful extent. Certainly, since they are mysteries, they could have been celebrated but not

recorded previously, especially in pre-Christian times, when the capital punishment for revealing

the mysteries was actually carried out.

In the case of Attis, we possess a significant account in Diodorus (3.58.7) of his death and

mourning, including the evidently annual ritual creation of his image by priests. Hence, these

noteworthy aspects of the Attis myth are clearly pre-Christian. Although Diodorus does not

specifically state that Attis was resurrected, the priests parading about with an image of the god is

indicative that they considered him risen, as this type of ritual is present in other celebrations for

the same reason, such as in the Egyptian festivities celebrating the return of Osiris or the rebirth

of Sokar….

…although we do not need Attis to show a dying-and-rising parallel to Christ, the material in

ZG1.1 concerning him is soundly based in scholarship. Regardless of when these attributes were

first associated specifically with Attis, the dying-and-rising motif of springtime myths is verified as

pre-Christian by the fact of its appearance in the story of Tammuz as well as that of the Greek

goddess Persephone, also known as Proserpina, whose ―rise‖ out of the underworld was

celebrated in the Greco-Roman world. That the festivals displayed by the Attis myth represent

spring celebrations and not an imitation of Christianity is the most logical conclusion. Indeed, the

presence of such a ritual in springtime festivals dating back to the third millennium BCE, as

Mettinger relates, certainly makes the case for borrowing by Christians, rather than the other way

around.135

Again, the reason these motifs are common in many places is because they revolve around nature

worship, solar mythology and astrotheology.

20.

Krishna, of India, born of the virgin Devaki with a “star in the east” signaling his

coming. He performed miracles with his disciples, and upon his death was

resurrected.

The sun is a prominent deity in the religions of India as elsewhere, dating back centuries to millennia.

Hindu literature from ancient times is full of reverence for the solar deity, the supreme light that inhabits

the visible disk. In the Gāyatrī Mantra, a Vedic scripture, the sun is revealed as the Supreme Godhead:

Let us adore the supremacy of that divine Sun, the Godhead, who illuminates all, who recreates

all, from whom all proceed, to whom all must return: whom we invoke to direct our understanding

aright in our progress toward his holy seat.136

Demonstrating its importance—and that of the sun to Indian religion—this ―mantra of the sun‖ is claimed

to be ―superior to all the mantras referred to in the Vedas.‖137 Indeed, the Gāyatrī is ―considered as the

‗Mother of the Vedas.‘‖138

The main Indian sun god is called Surya, but numerous other deities within the Hindu pantheon also

possess solar attributes and have been deemed sun gods as well. As another solar deity, the Indian god

Krishna‘s story follows a pattern of mythical motifs similar to the Christ myth.139 Krishna‘s solar nature is

135 Murdock, RZC, 15-16, For a discussion of the dating of various aspects of the Attis myth, see Christ in Egypt,

392ff.

136 This text represents an elegant paraphrase of the Gāyatrī Mantra by Indianist Sir William Jones. (See Balfour,

203.)

137 Pathar, 43.

138 Pathar, 43.

139 See Murdock‘s Suns of God: Krishna, Buddha and Christ Unveiled for more information on Krishna‘s solar nature.

clear from many of his characteristics and adventures, not the least of which is his status as an

incarnation of the god Vishnu. In this regard, Lalta Prasad Pandey remarks that Vishnu‘s solar nature is

―‗beyond doubt‘ and that the Vedas concur that Vishnu was a sun god.‖140 Says Pandey: ―Vishnu,

described in the Rgveda, is another solar deity.‖141

In the Bhagavad Gita, verse 10.21, Krishna states:

I am Vishnu striding among sun gods, the radiant sun among lights...142

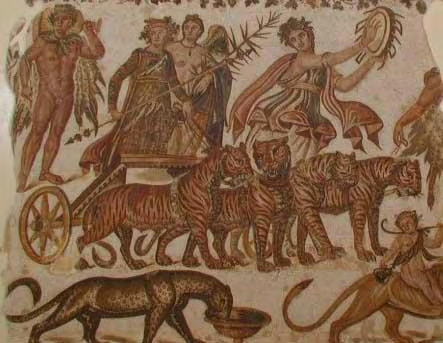

Surya in chariot driven by Aruna

Krishna in chariot driven by Arjuna

Just as Jesus was considered an incarnation of God himself, so was Krishna the incarnation of Vishnu in

a miraculous conception. In another sacred Indian text called the Vishnu Purana (5.1-3) we read:

…the supporter of the earth, Vishnu, would be the eighth child of Devakí…

No person could bear to gaze upon Devaki, from the light that invested her, and those who

contemplated her radiance felt their minds disturbed. The gods, invisible to mortals, celebrated

her praises continually from the time that Vishnu was contained in her person.... Thus eulogized

by the gods, Devaki bore, in her womb, the lotus-eyed (deity), the protector of the world....143

Born of a Virgin: Like Krishna, who is essentially a solar deity and not a ―real person,‖ so too is his

mother, Devaki, a mythical figure. Although the story becomes very complicated and far from its roots in

later retellings, the germ of the Krishna-Devaki myth can apparently be found in the Rig Veda, in which

the Dawn goddess gives birth to the rising Sun.144 This miraculous conception of a god incarnating

himself through a ―mortal‖ woman obviously compares to the gospel tale of Jesus‘s nativity.

Even though it is accepted that Krishna was another form of the Divine Vishnu, it is nevertheless argued

that because Devaki had other children prior to the birth of Krishna, she was not ―a virgin.‖ Yet, in

mythology the perpetual virgin is a common motif, regardless of how many children the female is said to

have given birth to. As Carpenter points out:

There is hardly a god whose worship as a benefactor of mankind attained popularity in any of the

four continents...who was not reported to have been born from a virgin, or at least from a mother

who owned the child not to any earthly father.145

140 Pandey, 17; Acharya, SOG, 183.

141 Pandey, 16.

142 Stoler Miller, 94.

143 Wilson, 264, 268.

144 Acharya, SOG, 222.

145 Carpenter, 156.

Indeed, the notion of a ―divine birth‖ is common in the ancient literature; although not always the same as

―virgin birth,‖ it is very close, by definition. In the Indian text the Bhagavad Gita (4:9), Krishna tells his

disciple Arjuna about his own ―divine‖ or ―transcendental‖ birth.

Moreover, while Devaki may have had other children, so too is Jesus depicted as having brothers and

sisters. For example, Matthew 12:46 refers to Jesus‘s ―brothers‖:

While he (Jesus) was still speaking to the people, behold his mother and his brothers stood

outside, asking to speak with him.

The scripture at Matthew 13:55-56 reads:

Is not this the carpenter‘s son? Is not his mother called Mary? And are not his brothers James

and Joseph and Simon and Judas? And are not all his sisters with us?

Despite apparently giving birth to all these children, Mary remains a perpetual virgin.146

Regarding this virgin-birth motif, Murdock states:

While the most common terminology concerning the status of Krishna‘s mother, Devaki, when

she gave birth to the god is that she was ―chaste,‖ another myth depicts her becoming a virgin

mother as a teenager after eating the seed of a mango. This apocryphal tale demonstrates that

the notion of the virgin mother existed in Hindu mythology, specifically applicable to Devaki, who

later became Krishna‘s mother. In the Indian epic the Mahabharata, parts of which were

composed centuries before the Christian era, the character Draupadi is a virgin mother, while the

book‘s supposed author, also named Krishna, is said to have been born of a virgin. Also in the

Mahabharata, the goddess Kunti remarks: ―Without a doubt, through the grace of that god, I once

more became a virgin.‖ Kunti is depicted as a ―chaste maiden‖—here unquestionably a virgin—

who is impregnated by the sun god Surya. Other ―born-again virgins‖ in this epic include Madhavi

and Satyavati.147

In consideration of the fact that a number of important figures in the Hindu sacred texts are

unquestionably depicted as virgin mothers—including Devaki as a teenager—it is understandable that

many writers have depicted Krishna‘s birth as virginal. For more on the subject, see Murdock‘s Suns of

God and ―Was Krishna‘s Mother a Virgin?‖

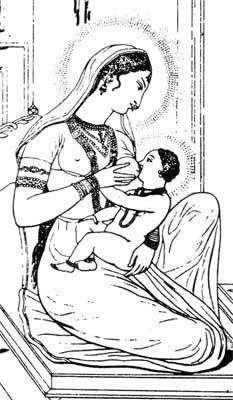

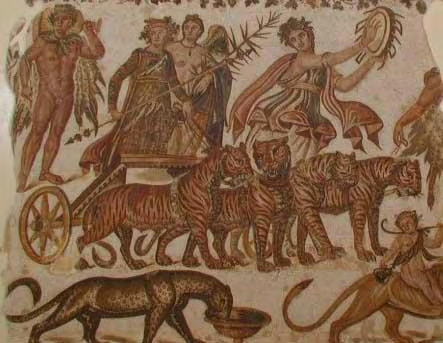

Devaki suckling Krishna

Virgin Mary suckling Christ

(Moor, Hindu Pantheon, pl. 59)

15th century

(Defendente Ferrari)

146 Catholic and other Christian apologists contend that these ―brothers‖ (and sisters) are either Jesus‘s cousins or

the children of Joseph by Mary.

147 Murdock, RZC, 17.

“Star in the East”: Although it is not specifically termed a ―star in the east,‖ in the Indian text the

Bhagavata Purana (10.3:1), a constellation called ―Rohini‖ or ―his stars‖ is present at Krishna‘s birth. As

professor of Hinduism at Rutgers University Dr. Edwin F. Bryant remarks:

At the time of [Krishna‘s] birth, all the constellations and stars were benevolent. The constellation

was Rohini, which is presided over by Brahma.148

Regarding this stellar motif, J.M. Robertson states:

Now, it is a general rule in ancient mythology that the birthdays of God were astrological; and the

simple fact that the Purana gives an astronomical moment for Krishna‘s birth is a sufficient proof

that at the time of writing they had a fixed date for it. The star Rohini under which he was born, it

will be remembered, has the name given in one variation of the Krishna legend to a wife of

Vasudeva who bore to him Rama, as Devaki...bore Krishna. Here we are in the thick of ancient

astrological myth. Rohini (our Aldebaran) is ―the red,‖ ―a mythical name also applied now to

Aurora, now to a star.‖149

The point here is that a celestial portent is common at the birth of great gods, legends, heroes and

patriarchs, as can be found in other stories and myths, including the Persian lawgiver Zoroaster, whose

very name means ―star of splendor,‖150 and Buddha, as the ―immortals of the Tushita-heaven decide that

Buddha shall be born when the ‗flower-star‘ makes its first appearance in the East.‖151 Hence, the story

about the star in the east at Christ‘s birth is an unoriginal and patently mythical motif.

Performed Miracles: Quoting Murdock:

Krishna‘s performance of miracles, in front of his disciples, is legendary, including many in the

Mahabharata, in which he reveals mysteries to his disciple Arjuna (John?). Krishna does likewise

in the Bhagavad Gita, in which he describes himself as the ―Lord of all beings,‖ among many

epithets similar to those found within Christianity. In this same regard, Krishna says: ―I am the

origin of al that exists, and everything emanates from Me.‖152

Death and Resurrection: Concerning Krishna‘s death and ascension, in The Oxford Companion to

World Mythology, Dr. Leeming states:

Just after the war, Krishna dies, as he had predicted he would, when, in a position of meditation,

he is struck in the heel by a hunter‘s arrow. His apotheosis occurs when he ascends in death to

the heavens and is greeted by the gods.153

Regarding the resurrection/ascension, the Mahabharata (4) says that Krishna or ―Keshava,‖ as he is also

traditionally called, immediately returns to life after being killed and speaks only to the hunter, forgiving

him of his actions:

…he [the hunter] touched the feet of [Krishna]. The high-souled one comforted him and then

ascended upwards, filling the entire welkin [sky/heaven] with splendour... [Krishna] reached his

own inconceivable region.154

Concerning Krishna‘s death, Murdock remarks:

Although it is not specifically stated that Krishna ―resurrects‖ upon his death—when he is killed

under a tree—he does ascend into heaven, alive again, since he is considered to be the eternal

God of the cosmos. Krishna‘s death is recounted in the Mahabharata and Vishnu Purana, both

148 Bryant, KS, 119.

149 Robertson, 177.

150 Zoroaster or Zarathustra has been credited with ―prophesying‖ the appearance of the ―star in the east‖ over the

place of the coming savior, as in the Arabic Gospel of the Infancy of the Saviour (10). (Roberts, ANF, VIII, 406.) This

―prophecy‖ is also considered to be the prediction of his own rebirth.

151 The star at Buddha‘s birth is said to be the ―Pushya Nakshatra‖ (Prasad, G., 25.) This episode of the star Pushya

at Buddha's birth is found in the Buddhist texts the Mahāvastu and the Lalita Vistara. (Edmunds, 123.)

152 Murdock, RZC, 17.

153 Leeming, OCWM, 232.

154 Rāya, 12.

claiming he was killed by a hunter while sitting under a tree, the arrow penetrating his foot, much

like Christ having a nail driven through his feet. In this regard, there have been found in India

strange images of figures in cruciform with nail holes in their hands and feet, one of which was

identified by an Indian priest as possibly the god Wittoba, who is an incarnation of Krishna.155

The impression of a resurrection is evident from the depiction of Krishna comforting his killer just after

death, before he has ascended into heaven. The point is that the god was once dead, but now he is alive

again, whether in this world or the afterlife. This type of detail does not suffice to undermine the fact of the

resurrection or raising up from death being a mythical motif in the first place, applicable both to Christ as

well as many other gods and legendary figures.156

21.

Dionysus of Greece, born of a virgin on December 25th, was a traveling teacher

who performed miracles such as turning water into wine, he was referred to as the

“King of Kings,” “God’s Only Begotten Son,” “The Alpha and Omega,” and many

others, and upon his death, he was resurrected.

It is wise at this point to recall that in the ancient world many gods were confounded and compounded,

deliberately or otherwise. Some were even considered interchangeable, such as Osiris, Horus and Ra. In

this regard, Plutarch (35, 364E) states, ―Osiris is identical with Dionysus.‖157 Thus, Zeus‘s son Dionysus

or Bacchus was considered the Greek rendition of Osiris:

Dionysus became the universal savior-god of the ancient world. And there has never been

another like unto him: the first to whom his attributes were accredited, we call Osiris: with the

death of paganism, his central characteristics were assumed by Jesus Christ.158

Dionysus is likewise identified with the god Aion and also referred to as ―Zeus Sabazius‖ in other

traditions.159 Hence, we would expect him to share in at least some of all these gods‘ attributes.

Dionysus returns from India

Mosaic pavement, 3rd cent. AD/CE

Sousse, Tunisia

(Patrick Hunt)

December 25th (Winter Solstice): As with Jesus, December 25th and January 6th are both traditional birth

dates related to Dionysus and simply represent the period of the winter solstice. Concerning these dates,

Murdock remarks:

155 Murdock, RZC, 17.

156 For more information on the mythical motif of the resurrection, see Murdock, CIE, 402-420.

157 Plutarch/Babbitt, 85.

158 Larson, 82.

159 Graves, R., WG, 335.

The winter-solstice date of the Greek sun and wine god Dionysus was originally recognized in

early January but was eventually placed on December 25th, as related by Macrobius. Regardless,

the effect is the same: The winter sun god is born around this time, when the [shortest day of the

year] begins to become longer….160

Murdock also says:

The birthday of Dionysus can be listed on both the 5th and 6th of January, while the god Aion who

is born on January 6th is called by Joseph Campbell a ―syncretistic personification of Osiris.‖

Dionysus was likewise identified with both Aion and Osiris in ancient times. In antiquity too, Jesus

Christ‘s nativity was also placed on the 6th or 7th of January, when it remains celebrated in some

factions of the Orthodox Church, such as Armenia, as well as the Coptic Church. Concerning

these dates, Christian theologian Dr. Hugo Rahner remarks:

As to the dates, Norden has shown that the change from January 6 to December 25 can

be explained as the result of the reform introduced by the more accurate Julian calendar

into the ancient Egyptian calculation which had fixed January 6 as the date of the winter

solstice.

It thus appears that in ancient times these dates of January 5, 6 and 7 represented the winter

solstice, which is fitting for sun gods. Indeed, Macrobius later places Dionysus‘s birth on

December 25th, again appropriate for a sun god.161

Jesuit theologian Dr. Rahner further states:

...in the Hellenistic East, and with Alexandria evidently taking the lead, a mystery was enacted

that concerned the birth of Aion by a virgin and that this mystery took place on the night leading to

January 6. It is quite immaterial whether the object of the cult in question was really Dionysus

Aion or some other deity. Epiphanius, quoting other ancient writers, tells us elsewhere that the

birthday of Dionysus was celebrated on January 5 and 6, though in the present instance it may

well have been that of Osiris or Harpocrates-Horus. It matters very little, since the tendency in

these late Hellenistic days was for the identities of gods, all of whom were beginning to take on

the character of a solar deity, to become merged with one another. We know that Aion was at this

time beginning to be regarded as identical with Helios and Helios with Dionysus…162

The pertinent passage in the writings of Church father Epiphanius mentioned by Rahner relates:

On this day, i.e. on the eighth day before the Calends of January, the Greeks...celebrate a feast

that the Romans call Saturnalia, the Egyptians Cronia and the Alexandrines Cicellia. The reason

is that the eighth day before the Calends of January forms a dividing-line, for on